About Time

By Brian Eggert |

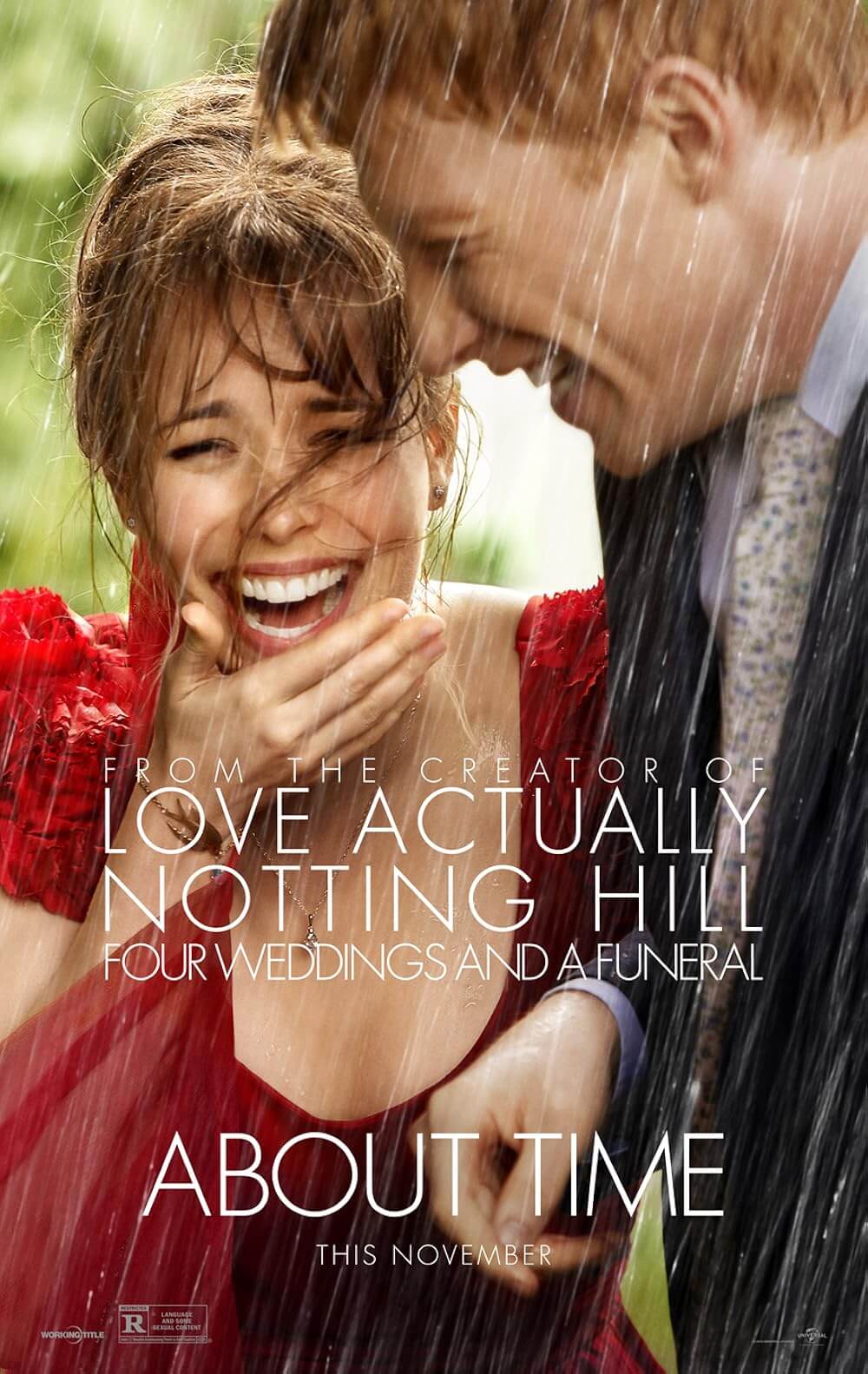

British writer-director Richard Curtis is a great observer of the simple beauty found in life and love. In his 2003 commercial hit Love, Actually, he bookends the film with images from connections made in an airport. “Whenever I get gloomy with the state of the world,” Hugh Grant’s Prime Minister narrates, “I think about the arrivals gate at Heathrow Airport. General opinion’s starting to make out that we live in a world of hatred and greed, but I don’t see that. It seems to me that love is everywhere.” Curtis takes that concept further in About Time, his sci-fi-infused romance that settles on the warming notion of acceptance and appreciation for the world around you. To explore, he considers what it would be like to go back in time to relive and correct your minor moments of staircase wit or major romantic regrets. It’s about the small things. What would be different in your life if you changed a discomfited New Year’s Eve handshake into a generous midnight kiss? If you could help turn a friend’s play from a disaster into a rousing success?

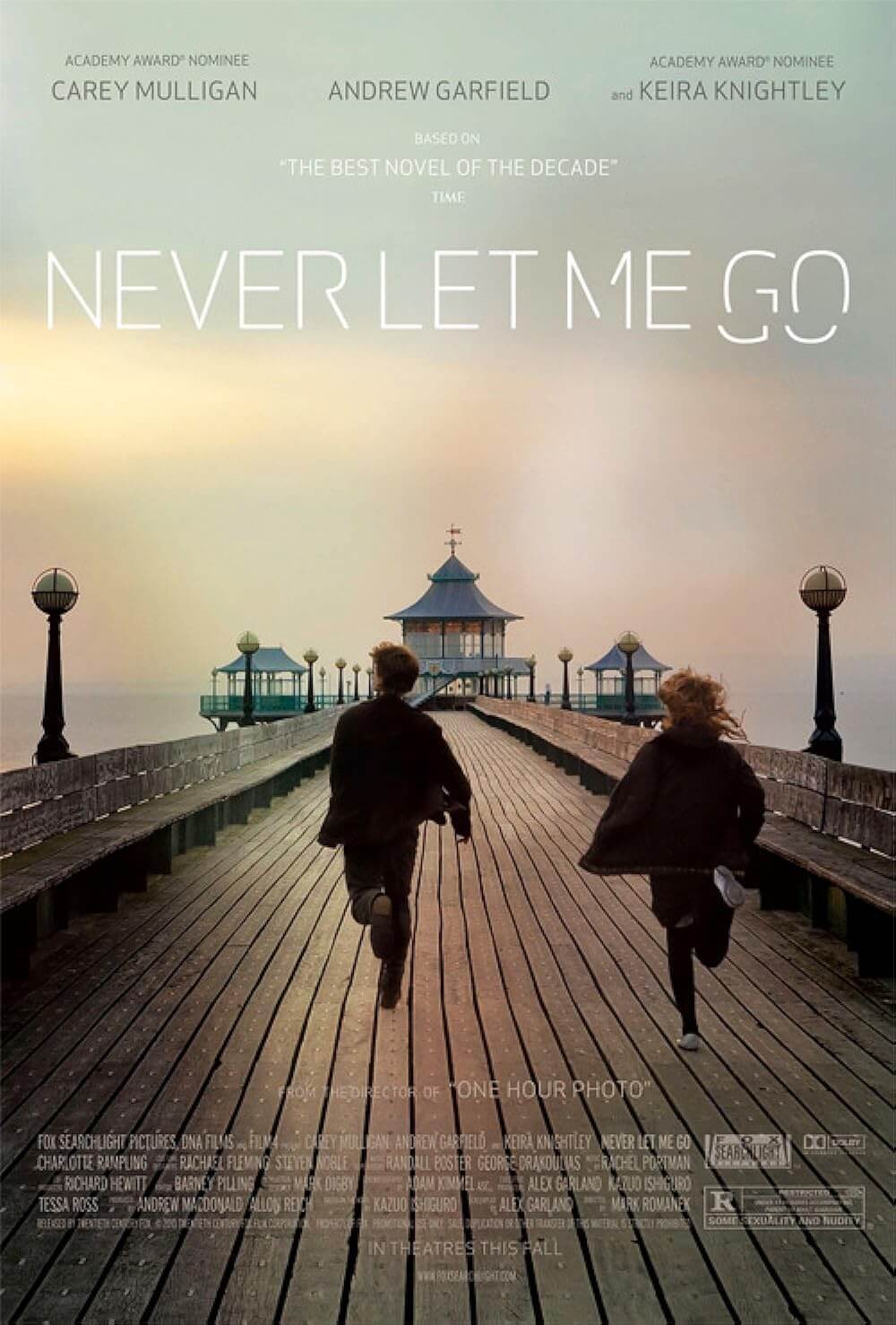

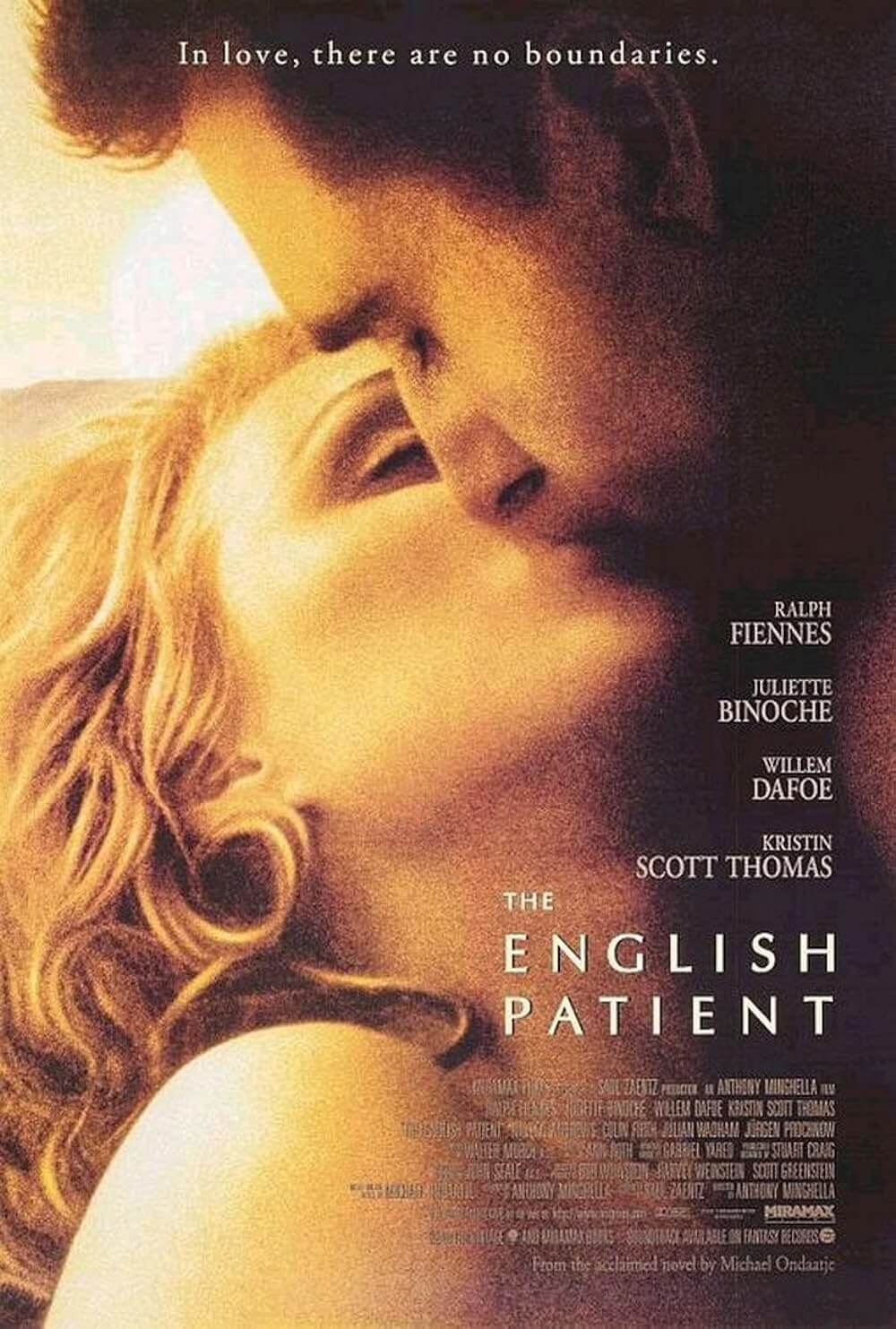

Curtis wrote the screenplays for Four Weddings and a Funeral and Notting Hill, both of which starred Hugh Grant opposite an American actress (Andie MacDowell in the former; Julia Roberts in the latter). He embraces the same character arrangement with Harry Potter alum Domhnall Gleeson in the amiably awkward Hugh Grant role, here called Tim. Having twice played the object of her time-traveling beau’s affection in The Time Traveler’s Wife and Midnight in Paris, Rachel McAdams is perfectly delightful as Mary, with whom Tim falls helplessly in love. But before that happens, though, Curtis explores the desirable home of Tim’s family, complete with dispassionate mother (Lindsay Duncan), quirky dad (Bill Nighy), absent-minded Uncle D (Richard Cordery), and zippy younger sister Kit Kat (Lydia Wilson). Tim’s family is frustratingly bourgeois and already privileged with their Cornwall-based mansion perched on a cliff with an ocean view, leaving some of us less fortunate to believe that Tim’s already got it pretty good—that his eventual talent for time travel is somewhat superfluous. But then, this is romantic science-fiction, not reality.

However, the time-travel plot device isn’t central to About Time. In fact, there’s no technical science to this sci-fi notion at all. As Dad explains on Tim’s twenty-first birthday, all Tim needs to do is enter a dark room or closet, clench his fists, close his eyes and think of when he wants to be, and—Poof!—he’s there. Curtis makes no attempt to explain this ability, except to say that the men in Tim’s family have it exclusively, whereas the women in the family remain unaware the power exists. But never mind the details, as Curtis employs the device as a dramatic doorway into our choices and regrets in life. Of course, the success of any time travel film requires strict rules, and those in About Time are outlined enough to meet the modest requirements of the story. “You can’t kill Hitler or shag Helen of Troy,” Dad explains with a smile. He can only move back to moments in his own life, which means he can correct mistakes or make different choices. Going back too far could unravel some crucial detail, however.

Early on, Tim uses his new talent to find a girlfriend, but he soon learns he cannot force love, no matter how much time he’s given. While some of us might consider the grander possibilities of the gift (fame and fortune), Tim’s father offers some good advice, having used his own ability to read books and play table tennis, to simply live his life and find happiness. And so, Tim moves to London to become a lawyer, rooming with hilarious acerbic playwright Harry (Tom Hollander), and he soon meets Mary at Dans le Noir, a London restaurant where patrons eat in pitch blackness, serving up a delightful meet-cute. We see Tim fix several gaffes and moments of clumsiness with Mary, and he relives their first time in bed together, changing it from a disappointment into an exhausted triumph, and then once more just for good measure. In another sequence, he tries to prevent an auto accident involving Kit Kat but realizes some events were meant to be. He and Mary eventually have a lovely marriage, a wedding ceremony charmingly spoiled by rain; they have children and face a number of family struggles along the way. Through it all, Tim learns to relive sparingly and savor time as it is.

Some may question the authenticity of Tim and Mary’s relationship, given that he never admits his ability to her and that he can essentially mold himself to fit her image of the ideal man. Just as some may question why Curtis’ films usually revolve around wealthy, pointedly white socialites in London. But just like a Woody Allen film, the director’s particular modes of romance are his own, despite being narrow at times. Curtis has his trademarks as a screenwriter, and audiences will either accept his unbelievable scenario and fanciful characters or not. From Four Weddings and a Funeral to Pirate Radio, Curtis employs familiar tropes, usually an agreeable leading man enamored with an eccentric girl, and they’re both surrounded by friends and family who are varying degrees of silly and embarrassing. Also, Curtis’ heavy use of music, from Mike Scott’s “How Long Will I Love You?” to Nick Cave’s “Into My Arms”, amplifies the proceedings with occasional heavy-handedness.

Curtis’ treatment is light and affable, as he always assembles an enchanting cast: Nighy plays the most loving, unconventional father you’ll ever see; Hollander’s dry sarcasm is riotous; Gleeson and McAdams have immediate, effortless chemistry. They’re all contained within a lovely package that some audiences may find too pleasant, too sentimental for its own good. And, to be sure, no one should be blamed for finding the material far too syrupy. That the conflict of Curtis’ screenplay isn’t pressing and resolves to engage the sometimes episodic quality of life is ironically its strongest characteristic, and also Curtis’ most criticized proclivity. What matters are not the unrealistic, fancifully romantic ways in which Curtis portrays his characters but the wisdom he offers about how they resolve to live their lives. The purpose of About Time is incredibly undemanding yet wholly endearing and insists merely that its audience set aside their disbelief for a saccharine story wherein life is celebrated for its basic pleasures.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review