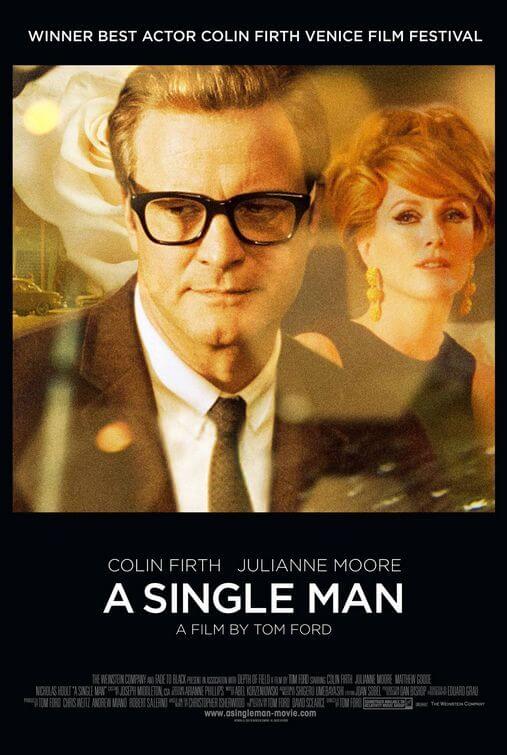

A Single Man

By Brian Eggert |

After watching A Single Man, it should come as no surprise that its director, first-time filmmaker Tom Ford, was once a Gucci fashion designer. The film was not so much directed as it was designed. Every shot feels meticulously composed, from its framing to its use of color. The gorgeous and meticulously conceived 1960s sets and clothing lend a sense of wistful period appeal, while the film’s controlled use of color makes for an overused metaphor, albeit a beautiful one. The artistic merit behind Ford’s production is impossible to deny if overbearing in the unfortunate way it distracts from the story.

This is a regrettable truth because the tale behind Ford’s visually stunning artifice has high dramatic potential, thanks largely to Colin Firth’s moving performance. Firth plays George Falconer, an English professor at a small Southern California university. It’s 1962, and the media is buzzing with the progressing Cuban Missile Crisis. But George is oblivious, as he has his own personal crisis, which involves ending his life later that night. After sixteen years with his partner, Jim (Matthew Goode), George is alone. Several months ago, Jim was in a fatal car accident. Now George wakes up every day dreading his dull routine; none of it has any meaning without Jim. His longtime friend Charley (Julianne Moore) offers little consolation, whereas one of his students (Nicholas Hoult) may help prove that moving on is possible.

Ford captures George’s despair by filming with an absence of color, showing only the muted hues of George’s life. These pale colors linger with the protagonist’s indifference toward his now monotonous and meaningless existence, but they brighten with those rare moments when George finds joy. Ford boosts the color to near-Technicolor extremes when a rare moment of pleasure finds George. He sees the neighbor girl, a carefree and innocent spirit whose light blue dress seems to radiate from the screen; an attractive James Dean-esque drifter offers George a cigarette, and the man’s lips and dark skin almost glow. Ford’s color metaphor continues throughout the picture, used perhaps too often to be subtle or clever. But then the director also employs a stark black-and-white monochrome for one flashback about Jim, which seems strangely out of place in a film where color is the equivalent of happiness.

This overstated color metaphor replaces the director’s need to make George’s grief feel real; instead, the character’s anguish disappears into the visual style, which upstages the fine acting. Firth has never been better, playing a low-key type that an audience must read through nuance. Except, the audience isn’t given the chance to fully absorb the layers of Firth’s performance because of Ford’s assaulting visual style. The characters around George keep telling him how awful he looks, asking him if he’s okay today, but the audience is oblivious, preoccupied with Ford’s dominating approach that refuses any natural response to the characters.

Several supporting roles go from misunderstood to downright perplexing because of Ford’s fixation on style. Consider Julianne Moore’s friend character, Charley; the performance, while typical of Moore and overacted to jarring effect, lends little insight to George. Her scenes with Firth feel incongruous and manic-depressive, going from extreme lows to baffling highs in an instant. Or there’s Ginnifer Goodwin’s role as George’s kind neighbor, who looks as though she was lifted from a bizarre dream concerning the flawed American ideal. These characters don’t seem to have any purpose in the story as it relates to George, other than to provide Ford yet another opportunity to exhibit his eye for (admittedly striking) 1960s-era interiors and clothing.

Based on the novel by Christopher Isherwood, A Single Man demonstrates exceptional control from a design perspective, which suggests this was a highly personal work for the director, something he wanted to ‘get right’ in every facet. Perhaps Ford was overthinking it. One could easily lose themselves in the hypnotic way Ford obsesses over George’s fascination with those rare, gorgeous details in his life, accentuated by bright colors. But the director’s technique overcompensates with style where the emotional turns of the story should have prevailed. These stylistic flourishes do the dramatic impact of the film a disservice by making the narrative less of a story and more of a superficial vessel for Ford’s unwavering design.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review