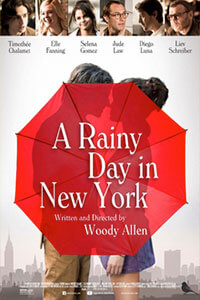

A Rainy Day in New York

By Brian Eggert |

Woody Allen films used to be events. Cinephiles poured over insider reports with minimal information about a mysterious “Woody Allen Fall Project” shooting in New York. Plot details would remain under wraps, but then someone like Robin Williams or Leonardo DiCaprio would be spied filming their scenes, piquing our interest. The film would premiere at a major film festival, usually with positive buzz. His films were reliably intriguing and came like clockwork, often one per year since the late 1960s. But over the last twenty years or so, Allen has gone through highs and lows, more than the previous three decades. For every Midnight in Paris (2011), there’s a Hollywood Ending (2002) to contend with; for every Blue Jasmine (2014), he delivers a forgettable You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010). Then Amazon Studios, who had a multi-picture deal with Allen and released his last two films, Café Society (2016) and Wonder Wheel (2017), backed out of their arrangement with the controversial director in the wake of refreshed accusations. His planned 2018 release, A Rainy Day in New York, remained shelved, aside from a minimal release in Europe and other non-U.S. territories. After two years of legal back-and-forths, followed by new distributors, Allen’s film finally dropped into theaters in the middle of a global pandemic.

Perhaps that’s for the best. The world hasn’t really needed a new Woody Allen film lately, and certainly not A Rainy Day in New York, a pretentious and eyebrow-raising story that combines several of the writer-director’s recurring motifs: a neurotic protagonist and his romantic woes; a love letter to the Big Apple; pseudo-intellectual jabs against pseudo-intellectuals. It also, if you can believe it, seems to comment on the Harvey Weinsteins and Kevin Spaceys of the film industry. However you may feel about Allen and the allegations against him (this is not an invitation to share), it seems particularly ill-advised for someone in his rocky position with the public to remark on or portray such characters in a lighthearted romantic comedy. Allen told an Argentinian news outlet that he’s “a big advocate of the Me Too movement” given his long history of championing actresses with strong roles for women. To be sure, Allen’s track record with performers like Diane Keaton, Dianne Wiest, and Penélope Cruz have created some memorable characters. Still, perception is everything, and this isn’t a good look.

At the very least, Allen, as ever, has selected a terrific cast. Timothée Chalamet headlines, doing a vague impersonation of his director. Alas, it’s my distinct displeasure to report that Chalamet plays a character named Gatsby Welles. What’s most unbelievable about that detail is no one stops to clarify, “Wait a minute, your name is what!?!” Instead, the story unfolds as our narrator, a tweed-wearing, upper-class elitist who prefers gambling to attending his college courses, plans to introduce his girlfriend Ashleigh, (Elle Fanning, excellent), to his beloved hometown, Manhattan. Gatsby is the type of Allen character who sermonizes about the romantic, dreary mood of the city he so loves, hoping his lady friend will feel the same. Inherently, we know from the outset that Gatsby and Ashleigh don’t belong together. After all, she’s a former beauty queen from Arizona of all places, and her parents are both bankers and (gulp) republicans. It’s obvious that Gatsby will end up with Shannon (Selena Gomez), a New York native, and the only other character his age willing to wander around the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A Rainy Day in New York takes a questionable turn when Ashleigh, a bubbly and impressionable journalism student interested in film, snags an exclusive interview with artsy, intentionally initialed director Roland Pollard (Liev Schreiber). When they meet, he asks her, “Would you like a scoop?” She replies, “Of…?” It’s one of the film’s funnier moments, and Fanning, who has played the ingénue before (The Neon Demon, Teen Spirit), proves she’s capable of playing the role for silly laughs (Ashleigh hiccups when nervous). Even so, dark things are happening around her, and Allen, unfortunately, plays them for laughs too. Ashleigh becomes embroiled in Pollard’s decision to abandon his latest film, and her story contains several cringe-worthy scenes of older men making passes at the 21-year-old student. Not only does Pollard make an indecent proposal that she should join him in France, but she’s pursued by Pollard’s recently cuckolded screenwriter (Jude Law) and heartthrob leading man (Diego Luna). We’re spared from having to watch these propositions succeed, but their attempts at seduction are no less uncomfortable to watch.

The pleasure of Allen’s films in recent years usually involves his choice of cinematographer (Darius Khondji, Javier Aguirresarobe, Vilmos Zsigmond, etc.). If his last couple of releases have been passable, it’s because Vittorio Storaro shot them, making everything onscreen feel like a dream. A Rainy Day in New York is an attractive film at times, though not as memorably stunning as, say, Wonder Wheel. Storaro lights simple scenes with a burning orange palette, while the overcast skies that Gatsby so loves seem oddly bright, calling attention to the lazy addition of sometimes CGI rain. The result doesn’t capture the romantic ideal that Allen, and Gatsby, hope to preserve in their long ruminations about the cozy, gloomier mood of New York. Maybe that’s because the viewer spends so much time worrying about Ashleigh, who admittedly seems to be enjoying her tour of the city with film industry icons, even though she seems blissfully unaware that she’s surrounded by predators. In this context, the rain seems ominous, but it’s no less pleasant in scenes with Gatsby and his insufferable jealousy of Ashleigh’s ambition.

At one point, Pollard’s film is called an “existential steaming shitpile.” Fortunately, A Rainy Day in New York isn’t quite so bad as that. It’s filled with pretentious characters who have absurd names, but they’re played by likable actors who give confident performances (most of Allen’s cast has since donated their salaries to women’s organizations and apologized for working with him). Still, it feels patchy and unfocused at times, deviating from his precious New York story to make outmoded observations about younger generations. In a brief scene, Gatsby interacts with a movie enthusiast who pokes fun at “wimps” who like classic movies, and it can’t help but feel like Old Man Allen shaking his fist at kids today. Rather than expressing his love and affection for his nostalgic ideals about Manhattan, Allen spends too much screen time dwelling on ideas that reveal he’s out of touch, and what’s more, he’s not willing to accept that he’s out of touch.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review