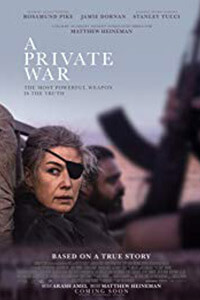

A Private War

By Brian Eggert |

“You’re not going to get anywhere if you acknowledge fear,” says Marie Colvin in an interview. “That comes later.” This archival footage of Colvin appears at the end of A Private War, a narrative film about the correspondent who famously embedded herself in the most dangerous war zones imaginable: Sri Lanka, Iraq, Kosovo, Libya, Iran, and Syria, to name a few. The real-life interview footage, a common type of coda in today’s based-on-a-true-story films, gives audiences a brief glimpse of Colvin’s mannerisms, as well as how she deployed straightforward, unflinching messages from a place of raw sensitivity. Employed by London’s Sunday Times, the New York-born journalist avoided official military escorts or government policies regarding press access, sneaking away on her own to find the human face of bloody conflicts that officials never want reporters to discover. But confronting the most brutal and inhuman struggles on the planet comes at a great cost, as indicated by her stark black eyepatch and a laundry list of personal problems.

It’s somewhat fitting that director Matthew Heineman makes Colvin’s story his first venture into narrative filmmaking. Heineman has also explored dangerous subject matter in his documentaries: Cartel Land (2015) examined the Mexican drug trade and the vigilante groups that risk their lives to oppose it; City of Ghosts (2017) followed Syrian rebels who fight against the ISIS takeover of their country. Much like Colvin, Heineman took vastly complicated issues and distilled them down to a humanitarian struggle for survival, weighing the human toll of conflicts that often feels a million miles away. Along with the skilled and atmospheric cinematography by Robert Richardson, the director puts the viewer alongside Colvin in convincing recreations of actual events. Some moments seem frenetic and uncontrolled, yet also dynamically shot, so the viewer feels immersed in the proceedings and perhaps only aware of their visual competence as an afterthought.

Central to A Private War’s effectiveness is star Rosamund Pike, playing Colvin in a performance that volleys between admirable strength and searing vulnerability. Despite her willingness to enter impossibly treacherous locations and risk her life for a story, Colvin was not unfazed. Arash Amel’s script dramatizes scenes that blend her inner trauma with everyday life; she returns home from an awards reception in her honor only to enter into a fragmented nightmare of horrific memories. Pike appears with a perpetual cigarette or glass of vodka, Colvin’s substances of choice, used to mute the chaos in her head. Much like those vices, however, being-there journalism was an addiction of Colvin’s. Just as soldiers become addicted to the high-energy strain of the battlefield, the most dangerous situations compel her toward them, even if they leave her hospitalized for PTSD.

A Private War’s title may be on the nose given the subject matter—it was based on the 2012 Vanity Fair article “Marie Colvin’s Private War” by Marie Brenner—and the film occasionally drifts into similarly banal descriptions of the character. As she recovers from her psychological scars in an institution, Colvin receives a visit from her colleague, photographer Paul Conroy (Jamie Dornan). She decries the “psychobabble” of doctors who need to explain-away her behavior and addictions, sarcastically listing the actual causes, including her two miscarriages, conflicts with her parents, relationship with food, and overwhelming self-pity. However reductive this scene proves, Pike manages to capture the faux strength it requires for Colvin to casually announce her personal problems, even as it’s evident that these issues genuinely affect her. Or watch the way Pike’s Colvin jokes about getting her eyepatch from “Treasure Island” in one scene, but later has a vulnerable moment in front of the mirror without it. After this and her mysterious presence in Gone Girl (2014), Pike has become a master of characters who say one thing, do another, and think yet another thing.

Between the volatile scenes in Sri Lanka, Libya, and Syria, Colvin attends galas in her honor and contends with some shaky personal relationships. Sex is another way of tuning out the ruckus in her mind. Greg Wise plays her supportive ex-husband, a writer of naval books with whom Colvin could not have children. At the beginning of the film, they still have a romantic relationship despite their divorce, yet he’s cruelly absent after Colvin loses the use of her eye. Later, Stanley Tucci appears as a Colvin’s easygoing lover, inviting her on one of his “sexual adventures” but without the emotional pressure of earlier romantic commitments. Elsewhere, her concerned friend Rita (Nikki Amuka-Bird) questions her drinking, while Rita’s daughter reminds Colvin of what she never had in a family. Above all, her editor (Tom Hollander) tries to keep her away from the risky stories after she loses her eye in Sri Lanka, but it’s no use. At the very least, he reminds her why her brand of authentic journalism remains important: her willingness to confront the stories that people would rather not see is vital, regardless of how it scars her mind and body. “The real difficulty is having enough faith in humanity that someone will care,” she says, in the film’s uneven use of voiceover.

Colvin was killed during a bombing raid on Homs in 2012, just hours after speaking live on CNN about what she had seen—proof that Bashar Assad was bombing innocent civilians and not the “terrorist gangs” he claimed to be. Unfortunately, Amel’s script structures the film’s events as a countdown to her death, such as “Sri Lanka – 11 Years before Homs.” The choice creates tension, suggesting a culmination of Colvin’s potential for self-destructiveness and her refusal to turn away from the harsh reality of a humanitarian story. But that tension feels overly dramatized for a story rooted in almost documentarian action, as many aspects of A Private War do, from the frequent speeches about her worldview and journalistic philosophy to the inconsistent use of her narration. Even so, Pike gives an outstanding performance in a film that, somewhat awkwardly, doubles as a reminder of the atrocities occurring in Syria. Perhaps that’s what Colvin would have wanted—a portrait that shows her compassion and inner experience, yet without avoiding the cruel reality of what’s happening in the world.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review