Reader's Choice

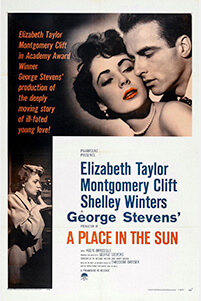

A Place in the Sun

By Brian Eggert |

When it was released in 1951, A Place in the Sun boasted two of the era’s most attractive stars, Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor, in a motion picture that, despite its romantic surface, doubles as a sordid portrait of a capitalist society. Somehow, in the midst of the Red Scare and McCarthyism, a film that reeks with the intensity of 1950s youth culture, a disenfranchised lot that aspired to have it all and were willing to do anything to join the hedonistic highbrows, became the year’s third-largest box-office grosser and winner of six Academy Awards. Although the press at the time were quick to note Charlie Chaplin’s praise to director George Stevens (“This is the greatest film ever made about America”), he didn’t mean that as a compliment to the country. Based on Theodore Dreiser’s 1925 novel An American Tragedy, the film considers a pointedly American definition of success in which one abandons morality to service superficial desire. No wonder Chaplin was forced to leave the U.S. and live in exile a year after the film’s release.

Unlike many classics that endure from Hollywood’s Golden Age, the urgency of A Place in the Sun’s commentaries and methods have softened with time, and the choices made by its characters have twisted further into the realm of unsympathetic vanity, making what should play as a tragic romance into an unsettling melodrama. The film is melodramatic in the traditional sense, not in the modern pejorative sense, in that it concerns issues of class division and sexual yearning. The young, self-educated man from the black sheep’s side of a well-to-do family wants the good life enjoyed by his relatives. He wants the American Dream of the 1950s: a good job, lots of money, and a pretty wife on his arm. And he could have it if not for his embarrassing, ultra-religious mother, not to mention his own lower-class impulses. Therein lies the tragedy. His identity is the very thing that prevents him from attaining what he desires. The story crescendos as the protagonist, George Eastman (Clift), nephew of ladies bathing suit magnate Charles Eastman (Herbert Heyes), comes ever closer to realizing his ambitions. And just as an opportunity presents itself, his past mistakes threaten to derail his progress, resulting in a dramatic downturn.

George’s religious mother (Anne Revere) makes it awkward when he arrives in town looking for work from the industrious Eastman family, but that doesn’t prevent Charles from securing a post for his nephew on an assembly line to learn the business. “You’re an Eastman, and you’re expected to act accordingly,” he’s told. There, George meets the dowdy Alice (Shelley Winters), a former farmgirl turned factory girl who, despite a company policy that prevents inter-office relationships, becomes George’s lover over the course of several months. All the while, George has his mind on the pampered Angela (Taylor), who he spied at one of Charles’ posh dinner events—to which George arrives underdressed, his necktie awkwardly hanging on the outside of his tweed suit, which isn’t a problem for the other, tuxedoed guests. Even as he learns that Alice is pregnant with his child, George pursues the good life with Angela, enjoying getaways in her convertible with her high-class friends. Meanwhile, the halcyon days of George and Alice have dwindled. Alice becomes a nagging, inconvenient, and homely presence next to the beauty of Angela. The only place he takes her now is to a doctor, in hopes that she can acquire an abortion—a detail that the Production Code required the film dance around, of course.

George’s religious mother (Anne Revere) makes it awkward when he arrives in town looking for work from the industrious Eastman family, but that doesn’t prevent Charles from securing a post for his nephew on an assembly line to learn the business. “You’re an Eastman, and you’re expected to act accordingly,” he’s told. There, George meets the dowdy Alice (Shelley Winters), a former farmgirl turned factory girl who, despite a company policy that prevents inter-office relationships, becomes George’s lover over the course of several months. All the while, George has his mind on the pampered Angela (Taylor), who he spied at one of Charles’ posh dinner events—to which George arrives underdressed, his necktie awkwardly hanging on the outside of his tweed suit, which isn’t a problem for the other, tuxedoed guests. Even as he learns that Alice is pregnant with his child, George pursues the good life with Angela, enjoying getaways in her convertible with her high-class friends. Meanwhile, the halcyon days of George and Alice have dwindled. Alice becomes a nagging, inconvenient, and homely presence next to the beauty of Angela. The only place he takes her now is to a doctor, in hopes that she can acquire an abortion—a detail that the Production Code required the film dance around, of course.

As his romance with Angela blossoms, and the two fall in love, thus securing the possibility of his better life in high society. At the same time, George repeatedly lies and breaks promises to Alice, refusing to marry her out of what he claims is a concern for their financial stability. Rather than break it off, he strings her along—and so, quite understandably, she expects George to marry her. But George no longer loves her, if he ever did. His desire that she just go away transforms into a murderous impulse when Alice interrupts a crucial Loon Lake weekend in his ascendancy and endangers any goodwill he’s established with Angela’s family, who are already skeptical of George’s dubious past and upbringing. Alice threatens to crash the party, so George proceeds to meet her. He promises to marry her and treats her to a romantic, secluded lake tour, all the while scheming to murder her. But his conscious and nerves get the better of him. George cannot carry out the murder; however, thanks to a freak accident, Alice drowns and, in doing so, fulfills George’s desire. Not that it matters. The authorities quickly catch on and arrest George for Alice’s murder. Though he is technically innocent—he did not shoot her, bludgeon her, or hold her head under the water—he made no effort to save Alice. In the ensuing trial, he is convicted and sentenced to death, a fate rendered somehow more tragic because of Angela’s unshaken love.

If A Place in the Sun is a timeless classic, it remains so because of the craftsmanship of its director and the talent of its stars. Stevens had always been a reliable Hollywood journeyman. He received his start at the age of 17 working for Hal Roach’s studio in 1923 on short films for Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. In the 1930s, he shifted to features at RKO, directing everything from musicals (Swing Time, 1936) to light-hearted comedies (Vivacious Lady, 1938) to adventure stories (Gunga Din, 1939). But after serving in World War II in the Army Signal Corps Special Motion Picture Unit, Stevens documented so much atrocity for the U.S. government that, when he returned in 1945, he harbored a more cynical outlook. His output became more substantial, more emotional, and often fatalistic. A Place in the Sun was his second postwar production after I Remember Mama in 1948, and he spent years assembling it. Most of the footage was shot in 1949 between the Paramount lot and locations in Lake Tahoe. He shot 400,000 feet of film (several times more than an average production) and took a year to edit it, but he assembled the material with intentionality behind every scene. Today, the film goes beyond readable. It’s obvious.

Consider how Stevens uses not

-so-subtle allusions to Alice’s drowning throughout the film, from the conspicuous painting of Ophelia in George’s dining room to Angela’s friends telling a morbid story about a woman who was drowned in Loon Lake by her beau. Or note how the film inserts a clumsy radio broadcast that anticipates Alice’s demise when it tells listeners to watch out for their mortality: “Make your holiday Death’s holiday too!” Stevens, meticulous though he was, was not subtle. In Franz Waxman’s score, there’s a questionable use of music from specific ethnicities—the Latin rumba on the radio in Alice’s bedroom contains a chaotic sexuality that Douglas Sirk would later employ in Written on the Wind (1956) and Imitation of Life (1959), while the scenes with George before and after Alice’s death play with a faux Native American war drum tempo. Other flourishes are more subtle. Stevens cross-cuts the social ladders on display as he shows Angela and her socialite friends at posh dinner parties, while George and Alice attend the cinema—considered, by the upper-crust anyway, the lower artform of the masses. Every detail in A Place in the Sun has a double meaning, and the viewer is never unaware of Stevens’ symbolism.

A Place in the Sun wasn’t the first time Hollywood adapted Dreiser’s novel. Paramount Pictures’ 1931 adaptation was directed by Josef von Sternberg and began a widespread discourse among the era’s film critics about the quality of adaptations from book to film. Critics focused not on the film itself but engaged in a comparison and contrast between the film and its source material, judging the film for the faithfulness of its adaptation. For instance, Variety wrote about A Place in the Sun by observing that “sex was a built-in quality of the Dreiser novel and Stevens’ apt direction leaves nothing to be desired in making the most of it.” Rather than taking into consideration how and why Stevens approached sex in his production the way he did—for romance more than a social commentary—writers from the period performed comparative analyses. Complicating matters, Dreiser’s book was based on an actual murder committed by Chester Gillette, who was executed after his 1908 killing of his girlfriend. Dreiser publically disapproved of Sternberg’s 1931 film and fuelled its mixed reception. And perhaps it was fortunate for Paramount that the author died before the release of A Place in the Sun, since the screenplay by Michael Wilson and Harry Brown was unfaithful as well.

In the 1932 Marx Brothers comedy Horse Feathers, when Groucho appears in a small boat with Thelma Todd, he asks, “Do you realize this is the first time I’ve been on a boat since I saw The American Tragedy?” This should give you some idea as to the ubiquitousness of Dreiser’s book, its initial adaptation, and the anticipation that led up to the release of A Place in the Sun. Clift and Taylor’s presence only heightened the attention it received, overshadowing the nature of the novel for something glossy and attractive. The film performed incredibly well, earning its budget back three times over. This may seem odd today since A Place in the Sun is rarely mentioned in the modern canonization of Classic Hollywood. But it was nominated for nine Academy Awards, winning for cinematography, costume design, editing, score, screenplay, and director. The Best Picture prize went to An American in Paris, while neither of the nominated actors (Clift, Winters) took home a statue—although the acting is among the few qualities that endure about the picture.

Clift and Winters each studied Stanislavski’s Method approach to acting, which demanded that an actor put their full emotional experience into a performance, even on a subconscious level. Clift immersed himself in the weak and insecure morality of his character, resulting in a nervous, sweaty performance. Winters downplayed her good looks with no makeup, playing it frumpy and pathetic. But their understanding of their respective characters varied. Winters played her role from start to finish as a dreary, but no less empathetic innocent in love who was seemingly destined to be disappointed by George. It can’t possibly work out for her. According to Patricia Bosworth’s biography of Clift, the actor argued with Stevens about Winter’s performance, suggesting she should be more sympathetic. Stevens at least understood Alice and directed her to be a lusterless character. Clift played his role under the notion that George is unsympathetic, unsophisticated, and ambitious, not realizing that his good looks would do a great deal to counteract his interpretation of George. At the same time, Taylor, then just 18, had made it big in Father of the Bride (1950), and she didn’t have to strain her acting muscles to play the privileged girl who falls in love with Montgomery Clift. Throughout the film’s production and release, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper fueled rumors of an off-screen affair between Clift and Taylor, adding to the idea that George and Angela belong together.

Clift and Winters each studied Stanislavski’s Method approach to acting, which demanded that an actor put their full emotional experience into a performance, even on a subconscious level. Clift immersed himself in the weak and insecure morality of his character, resulting in a nervous, sweaty performance. Winters downplayed her good looks with no makeup, playing it frumpy and pathetic. But their understanding of their respective characters varied. Winters played her role from start to finish as a dreary, but no less empathetic innocent in love who was seemingly destined to be disappointed by George. It can’t possibly work out for her. According to Patricia Bosworth’s biography of Clift, the actor argued with Stevens about Winter’s performance, suggesting she should be more sympathetic. Stevens at least understood Alice and directed her to be a lusterless character. Clift played his role under the notion that George is unsympathetic, unsophisticated, and ambitious, not realizing that his good looks would do a great deal to counteract his interpretation of George. At the same time, Taylor, then just 18, had made it big in Father of the Bride (1950), and she didn’t have to strain her acting muscles to play the privileged girl who falls in love with Montgomery Clift. Throughout the film’s production and release, Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper fueled rumors of an off-screen affair between Clift and Taylor, adding to the idea that George and Angela belong together.

The celebrity status of Clift and Taylor elevated A Place in the Sun at the time of its release. Or, at the very least, their presence in fan magazines surely appealed to the masses more than the film’s dig at capitalism. Coupled with the casting, Brown and Wilson’s screenplay turned the proceedings into a troubled love story, so that a viewer concerned only with seeing the two headliners appear romantically entangled onscreen would feel great sorrow over the events as they unfold. But it’s no tragedy that George and Angela cannot be together—or, it’s certainly not as mournful as the film treats it, especially given the pregnant Alice’s fate. The victim may remain a sad sack and the lesser option next to Taylor, but she’s also someone who proceeds with George out of love and a reasonable expectation that he do the responsible thing. Even so, the script, which makes a conspicuous choice to change George’s active murder in the book into an accident on film, ultimately convicts George for a thought-crime—he wanted her to die, and he does everything to premeditate her murder except the act itself. Whereas the tragedy of the source material was the collateral damage in the pursuit of a particular brand of American happiness, the tragedy of A Place in the Sun is that Clift and Taylor cannot be together. What about poor Alice? The film never mourns her, or her baby.

Later films, such as Woody Allen’s Match Point (2005), have a better handle on the difference between a tragic romance and a melodramatic critique of class ambition. A Place in the Sun tapers its warning about the pursuit of the American Dream in its concentration on the central romance, a cruel affair on George’s part that, today, the audience nonetheless wants to see because of the legendary stars involved. This is despite the underdeveloped character of Angela being little more than an attractive status symbol to George, and despite Winters’ excellent turn as a pitiable victim. It might be tempting to argue that the commentary, so praised by Chaplin, lies in George’s cold-heartedness. Except, the production’s intimate close-ups of Clift and Taylor, enhanced by Waxman’s stimulating score, ask the viewer to buy into the romance. The poster calls it a “deeply moving story of ill-fated young love!”—and without a wink of irony or cynicism better suited to filmmakers like Billy Wilder. It’s less surprising, then, that the film squeaked by those obsessed with stopping anti-American sentiments in the 1950s, since its statement is muddled. Even today, watching the otherwise capable film is an exercise in the appreciation of fine acting and competent direction, as opposed to a heartfelt tragedy, salient sociopolitical text, or believable romance.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Bosworth, Patricia. Montgomery Clift. Bantam Books, 1978.

Jellenik, Glenn. “The Task of the Adaptation Critic.” South Atlantic Review, vol. 80, no. 3-4, 2015, pp. 254–268.

Moss, Marilyn Ann. Giant: George Stevens, A Life on Film. Terrace Books, 2015.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review