A Nightmare on Elm Street

By Brian Eggert |

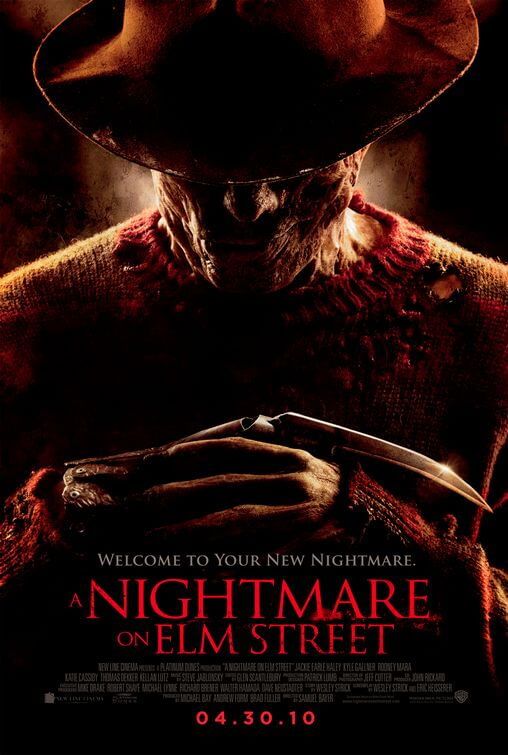

Platinum Dunes’ A Nightmare on Elm Street remake is a product more than a motion picture. The filmmakers take iconic imagery from Wes Craven’s 1984 original and rehash it for a modern audience, banking on the name-brand recognition of Freddy Krueger and his murderous, knife-fingered exploits of the unconscious to draw audiences. This is the same company that remade other such notable horror franchises such as The Amityville Horror, Friday the 13th, The Hitcher, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. They have no intention of making good movies, just selling enough tickets on opening weekend to generate a quick profit. So far they’ve been successful.

As a result of their objective, this remake comes off as exceedingly weak and unimaginative, despite its potential. The movie changes around a few plot details from the original but then refuses to elaborate on the franchise’s signature of elaborate, dream imagery-laden deaths. And so, once more, viewers see Freddy’s glove emerge in the bathtub of heroine Nancy (here played by the mousy Rooney Mara, who’s no Heather Langenkamp), we see a bimbo levitated from her bed and sliced up as her boyfriend watches in terror, and the finale ends with Nancy yet again pulling Freddy out of a dream, rendering him powerless and susceptible to harm. Writers Wesley Strick and Eric Heisserer modernize the story in a truly boring form, by simply repeating established ideas and images rather than reinventing them.

Just like before, a select group of teens in Springwood, Ohio are having trouble sleeping. They keep dreaming of a Boogey Man of sorts, someone donning a red and green sweater, brown fedora, homemade sheering glove, and burned flesh. He slashes at them in their dreams, and when they wake up, they find they’ve actually been slashed. The high-schooler victims, all played by actors well into their twenties, investigate and discover that they all have a secret past involving a disturbed preschool caretaker named Freddy Krueger. Their parents suspected Krueger of abusing the children, so they formed a mob and burned him alive. In a way, the movie almost plays like a mystery, and even, for a moment, suggests that Krueger might’ve been innocent and the parents were over-reactive. But then that would’ve been interesting, clever even, and this movie doesn’t have a clever idea in its entire runtime.

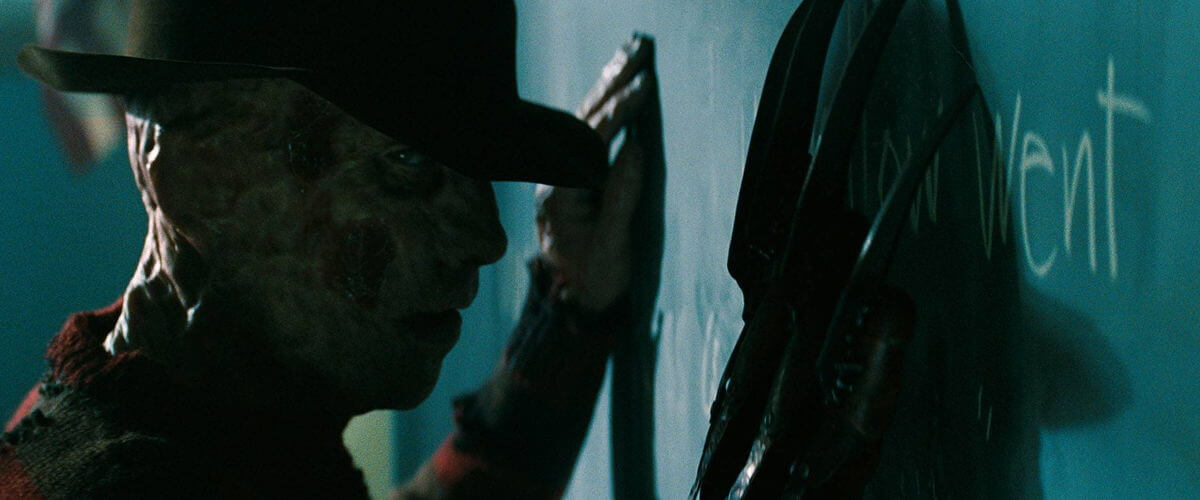

Playing Krueger this time around is Jackie Earl Haley, who interestingly auditioned for the role of Glen for Craven’s original, a part that went to Johnny Depp. Haley gives the role some weight, but the actor was more effective as a frightening child molester in Little Children. The makeup effects on Freddy appear more like that of an actual burn victim, making him less cartoonish looking. At the same time, Haley’s Freddy is presented as a true movie monster, whereas audiences rooted for Robert Englund’s version, who acted as the comedic host of his own twisted horror show. Here Freddy serves as a scary villain, but the teen characters are so incredibly bland that the audience is left with no one to root for. The original cared more about good-girl Nancy than the background character of Freddy. But somehow the remake has forgotten that the audience should care about someone—anyone—onscreen.

Director Samuel Bayer, who was recruited by producer Michael Bay, puts considerable care into the look of the movie, but the contemporary effects of the production are surprisingly low-grade. In a scene that mirrors one from Craven’s original, Freddy emerges from behind Nancy’s bedroom wall, stretching it like rubber. With merely a spandex sheet Craven accomplished this same trick and his version still holds up today, whereas Bayer uses CGI that appears about twenty years out of date (comparable to the same effect in Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners from 1996). None of the dream imagery used in the remake is memorable; and when your movie villain has the mind’s entire imagination to manipulate, it’s disappointing when he resorts to imagery you’ve already seen. Why not have Freddy try something new and exceedingly more terrifying? Why not truly unleash him in the mind of these teens?

Instead of really exploring the possibility behind Freddy Krueger’s power, which is quite original in terms of slasher villains, the filmmakers have taken the easy way out. A Nightmare on Elm Street is just as tedious as the other horror remakes by Platinum Dunes, avoiding any semblance of creative thought or innovative interpretation. The real nightmare is that audiences will probably see this movie, making it a minor hit, just enough for the company to validate producing a sequel that we’ll have to tolerate a year or so from now.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review