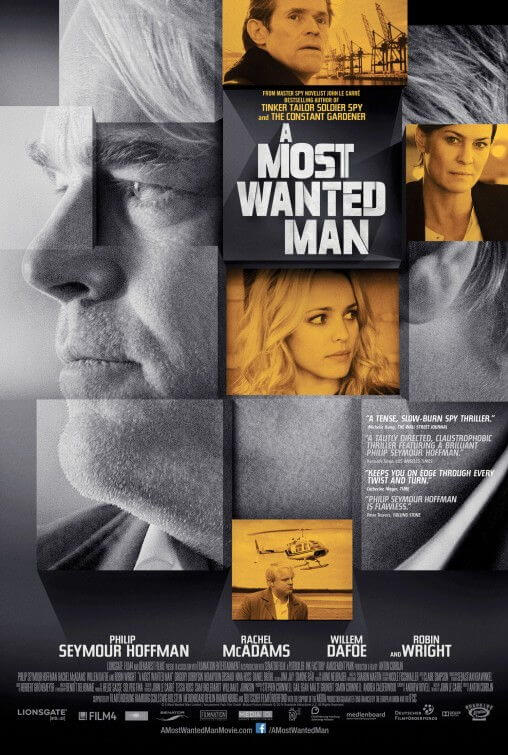

A Most Wanted Man

By Brian Eggert |

Anton Corbijn’s A Most Wanted Man is a European spy film in nearly every way, from its location and themes to the technical approach and behavior of its central spy. Based on the 2008 novel by master spy novelist John le Carré, the film carries not the pulse-pounding tempo of Hollywood spy-thrillers like the Bourne series or such related, actionized ilk; rather, it adopts the similarly textured and methodical, low-humming nuance of another le Carré adaptation, Tomas Alfredson’s version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy from 2011. In that vein, the maze-like plotting wraps the viewer in twists and turns without relying on explosions, shootouts, or grandiose melodramatics. Form follows function in Corbijn’s capable hands, as the story reveals an overarching theme about the current, pointedly American, post-9/11 approach to spy games, and the more intricate, more persistent, perhaps specifically European alternative.

Set in Hamburg, Germany, where Mohammed Atta and his collaborators prepared the 9/11 attacks, the story follows a concealed unit of German intelligence officers determined to catch not the terrorist, but the individual behind the terrorist—the idea being that if you chop off the head, the appendages stop moving. And when applied to spying, the idea is, should a potential terrorist be identified, allow them to continue to operate in the event that their presence in the field leads to their leader or financier. Such a philosophy is decidedly old-fashioned, whereas a more modern approach would be a jealous, justified concern for human life and aversion to chaos in the streets, suggesting that if there’s proof to condemn a suspected terrorist, then that individual should be detained immediately. The difference is going in guns blazing, or resolving to stand back with patience, watch carefully, and manipulate the players into showing their cards not one by one, but by dropping their entire hand.

In place of decapitation and poker metaphors, Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s character, Gunter Bachmann, a heavy drinker and smoker, a brow weighted with guilt and paranoia, says, “It takes a minnow to catch a barracuda, and a barracuda to catch a shark.” His long-game approach to spy tactics is unfavorable to those outside of his unit, including by-the-book local official Dieter Mohr (Rainer Bock) and, possibly, the resident CIA presence (Robin Wright), who seems to support Bachmann’s cause. When a young Chechen-Russian immigrant, Issa Karpov (Grigoriy Dobrygin), arrives in Hamburg, having endured much torture on behalf of his native lands, he goes into hiding and seeks the counsel of human rights lawyer Annabel Richter (Rachel McAdams). Issa claims to be the son of a former Russian military bigwig who left him a sizeable inheritance in a German bank managed by Thomas Brue (Willem Dafoe). Bachmann suspects a local, seemingly squeaky-clean Muslim leader, Dr. Faisal Abdullah (Homayoun Ershadi), may be funding terrorists and hopes to use Issa’s funds to ringer Abdullah.

Except, the mission is not only for Abdullah but for whomever Abdullah is supplying with funds to carry out acts of terrorism—in other words, the shark. Bachmann and his team must contend with modern reactionaries who want to stop immediate threats now, and while he recognizes the dangers of allowing a suspected terrorist to go about free (monitored closely, of course), he wants to make a real impact against terrorism. The late Hoffman, as one might suspect, delivers a masterful performance of understatement. His mouth bent downward and face unshaven, he looks bloated and, really, a mess. Bachmann is a man who has been defeated in the past in a similar operation—as we learn in a subplot only discussed in passing—and he carries his former blunder with him always. Beside him is Irna Frey (Nina Hoss), his beautiful female colleague with whom he shares hints of romantic interest, although those hints are never forced upon us as part of the story. They’re another symptom of Bachmann’s emotionless, detached, and discerning world.

Through high-level puppeteering of their targets and those involved, outlined efficiently by Australian screenwriter Andrew Bovell (Edge of Darkness), Bachmann and his team ignite slow-burning suspense that ends in poignant despair, capped with a pitch-perfect conclusion. If there’s one unconvincing element in the proceedings, it’s the German accents of McAdams and Dafoe; although the actors speak in English for the duration, their accents are confused and inconsistent. Hoffman, meanwhile, disappears into his role, as often he does, and carries the film on his shoulders. Corbijn, a photographer-turned-director whose previous films Control and, underwhelming, The American, are meticulous visual presentations within the understated drama. But the helmer’s cold touch, accented by earthy visual tones by cinematographer Benoit Delhomme, capably services le Carré’s brand of reserved espionage tale, and will supply those versed in such intricate spy yarns with a fascinating look at the modern intelligence community.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review