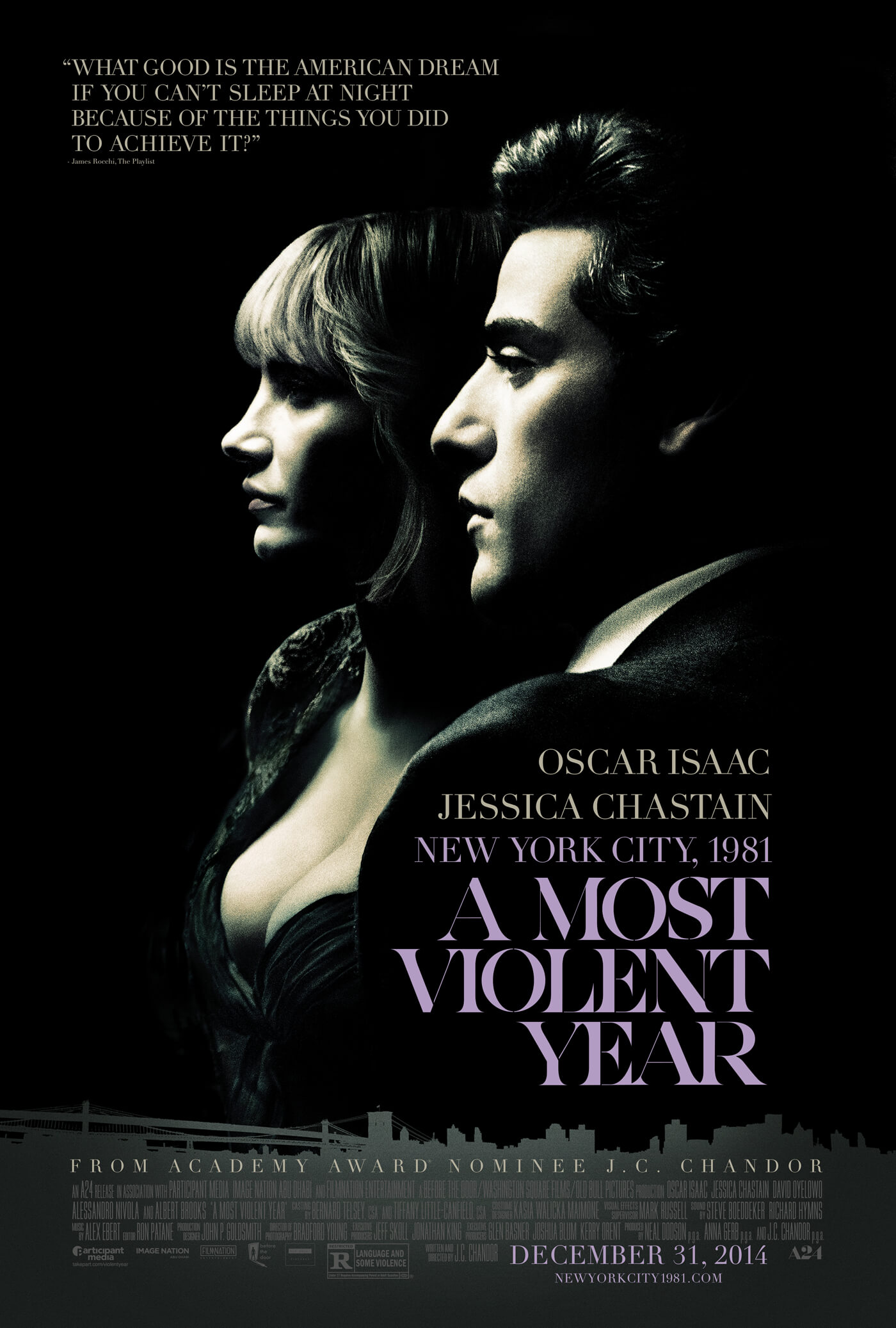

A Most Violent Year

By Brian Eggert |

In the New York City of 1981, crime has reached all-time highs, and Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac), the owner and operator of a heating-oil business that continues to grow, struggles to function by his own sense of principles. Throughout the city, his industry is run by Mafioso-type families who claim territories and have unwritten rules about how far competitors should expand. Abel isn’t interested in such rules beyond the limits of capitalism, though he respectfully networks with these families because he must. Abel takes pride in his running a fair and honest business. But his wife Anna (Jessica Chastain), whose gangster father used to own the company, may question how far he’s willing to go to protect his family and business in the face of ruthless, intimidating rivals. Abel just wants to conduct himself the “right way” to achieve his ambitious goals. But throughout J.C. Chandor’s A Most Violent Year, his principles are pushed to their extreme limits as wave after wave of peril threatens the things he loves.

The three films by writer-director Chandor thus far have similar themes about the American Dream; specifically, the prices some have to pay to achieve success or the downfalls that occur once success is achieved. Chandor’s 2011 debut Margin Call shows what happens to a high-powered Wall Street firm on the cusp of the 2008 financial crisis. In 2013, Chandor released the dialogue-less survival story All Is Lost, featuring Robert Redford as a successful man whose yacht suffers a breach in the hull and slowly begins to sink—and it’s clear his fortunate lifestyle has been mistaken for a sailor’s mastery. And now, with A Most Violent Year, and looking at all three films as coming from the same author, several themes in Chandor’s work begin to crystallize: each film follows characters who have almost no backstory, and the audience learns about them through observation; each film’s protagonist has created their own confined world founded on their own successes; each presents a conflict where the protagonist is, in a way, isolated with that world; and through their conflict, each film pushes the American Dream to its limits.

Despite the title and its allusions to gangsters, A Most Violent Year is not painted in strokes of onscreen violence, though occasionally, blood is shed. But the violence here is mostly psychological. The New York setting offers the tense atmosphere in which Abel attempts to control a number of moving parts at once. He and Anna have just moved into a suburban mansion with their two young daughters. He’s 30 days away from closing a commercial real estate deal that would grant boats access to deliver cheaper oil directly to his facilities, and without the need of middlemen, thus securing his business for years to come. To close, he’s put up his family’s entire savings as collateral. But the banks are getting wary because Abel’s drivers and salesmen are being violently attacked and hijacked in the field, presumably by competitors. The teamsters union for the drivers demand that they be armed with handguns to defend themselves, but Abel wants to run a clean business—so his choice is either to put his people in danger, or risk bad press if one of his employees shoots someone. Worse, the District Attorney (David Oyelowo) investigating corruption in the heating-oil industry has targeted Abel’s business with several indictments.

In another filmmaker’s hands, A Most Violent Year may have been set up like a thriller, but Chandor delivers a drama of intimate scenes where Abel’s very soul seems to hang in the balance. His attorney, played by Albert Brooks, suggests he arm his employees, which may not be the best legal advice. But the most interesting scenes occur between Abel and Anna, as Chastain isn’t a typical wife character for this milieu. Because her father was a gangster, Anna, who oversees the books for their business, has grown accustomed to the men in her life responding to threats with violence—something Abel refuses to do. He won’t take part in anything that makes his business look illegitimate. Nevertheless, there’s no limit to Anna’s resolve, and she challenges her husband to the point of humiliation, taking matters into her own hands a number of times throughout the film. She’s a strong character, someone who’s not afraid to face off against a D.A., and Chastain plays her skillfully. Likewise, Isaac is perfect and layered as Abel (just as he was in the Coen Bros’ Inside Llewyn Davis), capturing the character’s control and increasing tension that, though it never bursts (but comes very close), always lingers under the surface.

These scenes do not punch with dramatic flair or obvious turns of plot; though it involves crime and corruption, this is not a gangster film, and so audiences expecting it to play out like one of Martin Scorsese’s New York gangster pictures may feel disappointed. Chandor and his editor Ron Patane execute long, deliberately paced, almost quiet scenes, where dialogue takes over and we barely notice the hum of Alex Ebert’s score under the surface. This approach has an immersive effect that steeps us in the production details. Chandor further immerses us by realizing a 1980s mise-en-scène complete with the era’s rectangle cars, graffiti-sprayed buildings, and a vintage New York skyline (rendered with convincing CGI). Production designer John P. Goldsmith uses the period’s autumnal browns and oranges on furniture and wood panel walls, while costumer Kasia Walicka-Maimone uses the same pallet on the clothing. Cinematographer Bradford Young shoots it all through an appropriately soft but crisp filter that appears as though it was filmed in the 1980s. Perhaps the best compliment this critic can give to Chandor’s production is to compare its technical completeness to David Fincher’s Zodiac.

Though one might be tempted to accuse Chandor’s stance on the American Dream as being outright critical, that’s a thin interpretation of his films, especially after considering this latest work. Certainly, one could argue that his characters in Margin Call and All Is Lost are being punished for their past crimes (in the latter film, Robert Redford’s otherwise wordless character leaves a note that simply reads “I’m sorry,” and suddenly our perceptions of him shift—perhaps he is not as singular as he appears). But Chandor presents Abel as, arguably, innocent. After all, he’s named after the Old Testament’s innocent brother who, in the Book of Genesis, is the first human being to be betrayed and murdered. Abel’s business scruples are incredibly important to him, and the mere thought of betraying his own sense of honor offends him. As a result, several betrayals of that honor enhance the film’s drama. Chandor does not critique those who would try to operate fairly within a capitalist society; rather, he suggests that such a society is often cruel and unforgiving to those who participate in it. A Most Violent Year is a brilliant look at greed, hubris, and the effect of capitalism, and it cements Chandor as a distinctive voice in American cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review