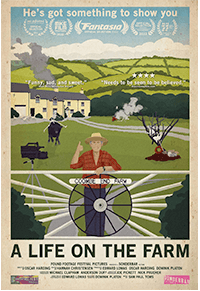

A Life on the Farm

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: Oscar Harding’s A Life on the Farm will arrive on VOD on May 9, 2023.)

“Dark… But like friendly dark.” That’s how one person describes the home videos made by Charles Carson, a farmer in Huish Champflower, a quiet village in Somerset, England. For about a decade, starting in the early 1990s, Carson made an ongoing series of home movies on VHS, capturing the everyday reality on his family’s Coombe End Farm. Some of the tapes he recorded as memorials, others for neighbors to enjoy or scratch their heads over, and others as personal expressions. Whatever their purpose, they’re the subject of A Life on the Farm, a documentary about a community of found-footage and VHS enthusiasts who rediscovered one of Carson’s tapes, which led to more tapes and plenty of questions about Carson. The knee-jerk reaction to Carson’s work seems to be morbid fascination, followed by bemused uneasiness, and finally, appreciation for his distinct personality and frank treatment of life and death. The experience is sort of like opening someone else’s diary and recoiling over what they’ve written, before ultimately recognizing that a fellow human being put their heart into this.

The story begins with Oscar Harding, the doc’s director, who saw one of Carson’s tapes as a child before his father abruptly shut it off—understandably so, since Carson has a matter-of-fact approach to the circle of life. Carson’s video, titled “Life on the Farm,” has a sequence that depicts a cow giving birth in detail—a commonplace sight for a farmer. However, Carson’s comfort level with what outsiders might perceive as confronting imagery provides the footage with an uncanny quality. Not long after the calf is born, Carson holds up a fleshy mass and says, “Have a jolly good look at a placenta.” Carson also filmed the burial of his family’s cat, placing cat food near the grave so the other farm felines would approach and seem to pay their respects. The most talked about example comes when Carson’s mother died, and he staged her body around the farm for days, shot footage with himself and her corpse, and then recorded her funeral. In a predictable observation, Karen Kilgariff of the My Favorite Murder podcast compared Carson to Ed Gein. But Carson wasn’t harming anyone or making lampshades out of human flesh.

While first impressions might indicate a backwoods weirdo, Carson was quite intelligent, if unconventional. In the middle section of his doc, Harding explores Carson’s life. He came from a line of farmers before taking a post as a college instructor of agriculture and farming equipment, which he maintained for decades before retiring to care for his aging parents. He married, had some children (the doc is fuzzy on just how many), played several instruments, and, obviously, had a knack for video—to the extent that he taught himself how to create in-camera special effects, narration, and creative editing techniques. But after the death of his mother and wife, he spent much of his later life on Coombe End Farm in solitude. Along with signs of Carson’s dementia, many of the film’s talking heads suggest his prolonged isolation contributed to his sometimes erratic behavior. Neighbors and friends report mood swings and obsessive tendencies. And his videos reveal someone who spends a lot of time inside his head, so perhaps making them kept him sane.

Much of A Life on the Farm consists of Carson’s footage, accompanied by commentary from VHS collectors and those who knew him. Harding doesn’t break the mold when constructing his film, but the subject remains fascinating throughout. By the end, everyone seems to agree that, at first glance, the tapes look like the disturbing product of an unhinged loner. Yet, looking closer, you see a person yearning to express himself through a creative outlet. What Carson made is an analog form of exhibitionism on social media. Instead of posting selfies on Facebook, reels on Instagram, or dancing videos on TikTok, he shot documentary footage of important life events, showcased his farm and animal friends, and even made fictional short films. Then he circulated the resulting tapes to friends and even a TV contest, earning him some local notoriety—only to be forgotten and now rediscovered. It all seems like the work of a creative hungry for attention.

A Life on the Farm debuted at Fantastic Fest to wide acclaim. Unfortunately, the doc runs a mere 75 minutes and concludes before it explores its subject with much depth. In the end, I was left with questions. Just how many hours of footage did Carson shoot? The filmmakers reference Carson’s children. What happened to them, and why didn’t they appear in this documentary about their father? Surely, some discussion about their relationship with him would have shed some light on another facet of Carson’s personality. Instead, the filmmakers take the VHS collector approach and resolve to say, “Check this out. Isn’t it weird?!” Yes, it is. It’s also quite sad, quirkily funny, and ultimately inspiring. After all, Carson made a pure form of personal expression and earned recognition for his art. Harding’s doc puts those videos, some of which have appeared online, in context within an accessible and engaging frame.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review