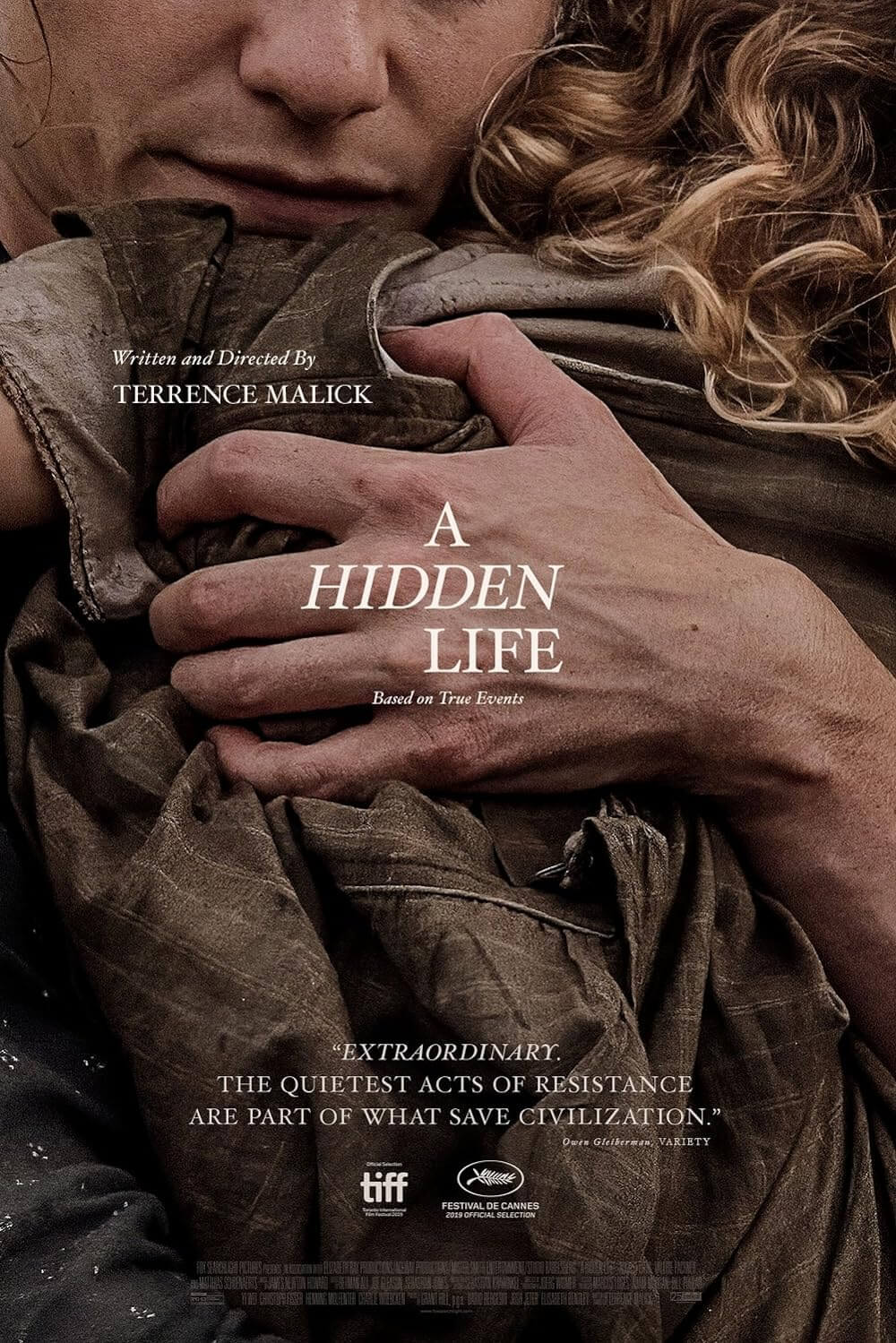

A Hidden Life

By Brian Eggert |

A Hidden Life sets celestial images of Nature against the most tumultuous period of world history in the last century. In the quiet Austrian hamlet of St. Radegund, the community of farmers and peasants has escaped into the mountains, secluded from the modern world. Amid the lush green hills and misty air, the villagers feel closer to their Christian beliefs of a God in Heaven who “won’t send us more than we can bear.” Their idyllic life consists of hard work in the fields, community gatherings rich with dancing and frivolity, and Sundays at church. It’s a simple, bucolic existence of uncommon beauty. But the year is 1939, and the idyllic community cannot escape the rise of fascism in their country. Written and directed by Terrence Malick as a powerful reflection of our present world, the film tells the true story of Franz Jägerstätter, played by August Dielh, a man confronted by the notion that “He who created this world created evil.” When Franz refuses to swear an oath to Adolf Hitler, he goes against the grain of his Christian countrymen who promptly concede to Nazi rule. In many ways a return to form for Malick, in other ways a bold step forward, A Hidden Life dramatizes a crisis of faith in a historical setting. But the film has a stirring message—undeniable in our present, analogous condition of rising fascism that has set the world ablaze, just as it had done in the 1930s—that even the smallest protest can have meaning, even if it exists solely within.

Eight years have passed since Malick won the Palme d’Or for his arresting, semiautobiographical The Tree of Life, and the subsequent years have proved divisive among critics and cineastes. Many believe that Malick has floundered with his increasingly poetic and ethereal To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2017)—films situated in a contemporary setting and rooted in an aesthetic of impressionistic imagery and structure; frequent scenes of twirling joy and pensive expressions of ennui; and an opacity that some have incorrectly labeled as non-narrative. When combined with Malick’s already ingrained concentration on Nature, his dominant use of light during the magic hour, his prevalent use of lyrical voiceover, and his existentialist concerns as an auteur, his films since The Tree of Life have challenged his earlier, comparatively straightforward and more universally hailed films. In this context, A Hidden Life may seem like the director has returned to a mode that defined his earlier work. However, that notion dismisses the artistic progress he has made, suggesting his less lauded pictures were somehow deviations from the path. But there’s a profound growth evident in his latest film, which adopts a less complicated structure yet imbues the material with the feeling of inwardness that defined his most recent works.

While I was moved by the romantic melancholy and searching quality of Malick’s last several films, his best material occupies the condition of a personal epic, which rarely comes out of today’s cinema. His historical films eschew much of the ideological background of their setting and focus instead on the individual’s journey in a dramatic period, and the metaphysical expedition his characters take to confront their frequent inability to grasp the horrors around them. The Thin Red Line (1998) focuses on how war reshapes—both the land and the soldiers thrust into the fight, unable to process war’s violence. And yet, it ignores the contextual factors of the Guadalcanal and its overarching importance in the war. In The New World (2005), the director explores the untouched lands of North America prior to European settlement, and how the indigenous population lived in step with Nature until the colonizers of Jamestown arrived. These films occupy a mode of human saga rare in film history, apart from a few examples: David Lean’s searching masterpiece Lawrence of Arabia (1962) posited the question “Who are you?” about its titular hero and, after four hours in the panoramic desert, refused to supply an easy answer. Francis Ford Coppola’s personal epics of the 1970s (The Godfather, Apocalypse Now), secured his place in the pantheon of great filmmakers. And Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) indulged in the mode, though many waited decades before they embraced it.

While I was moved by the romantic melancholy and searching quality of Malick’s last several films, his best material occupies the condition of a personal epic, which rarely comes out of today’s cinema. His historical films eschew much of the ideological background of their setting and focus instead on the individual’s journey in a dramatic period, and the metaphysical expedition his characters take to confront their frequent inability to grasp the horrors around them. The Thin Red Line (1998) focuses on how war reshapes—both the land and the soldiers thrust into the fight, unable to process war’s violence. And yet, it ignores the contextual factors of the Guadalcanal and its overarching importance in the war. In The New World (2005), the director explores the untouched lands of North America prior to European settlement, and how the indigenous population lived in step with Nature until the colonizers of Jamestown arrived. These films occupy a mode of human saga rare in film history, apart from a few examples: David Lean’s searching masterpiece Lawrence of Arabia (1962) posited the question “Who are you?” about its titular hero and, after four hours in the panoramic desert, refused to supply an easy answer. Francis Ford Coppola’s personal epics of the 1970s (The Godfather, Apocalypse Now), secured his place in the pantheon of great filmmakers. And Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) indulged in the mode, though many waited decades before they embraced it.

From the first moments of A Hidden Life, it’s apparent that Malick is up to something unique in his career, which distinguishes the film less as a return to form than a necessary evolution. Opening with the title “The following story is inspired by real events,” the film’s first shots of black-and-white war footage show German propaganda—Hitler’s speeches, Nazis marching in the street, and brief glimpses of the 1934 Nuremberg Rally shown in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935). It’s uncommon for Malick to establish a setting in this historically grounded way, but the footage implants a sense of tangible dread that leaves the situation clear just in case the surroundings were unfamiliar (the modern viewer of The Thin Red Line, for instance, could be forgiven for not grasping the significance of the Guadalcanal). Still, other elements of the film prove more familiar. His soundtrack echoes with his usual selections from Bach, Beethoven, and Handel, while his camera observes Nature with a delicate eye. Long, thoughtful shots of the Upper Austrian mountains lend a sense of awe, and shots of Franz and his wife Franziska (Valerie Pachner) enjoying an arcadian life with their daughters contain an earthbound joy. Yet, these familiar moments from Malick’s oeuvre have been captured in a combination of digital and traditional photography by cinematographer Joerg Widmer—replacing Emmanuel Lubezki who shot all of Malick’s films between The New World and Song to Song—marking yet another step in a new direction.

In a way, Malick tells a story similar to those in The Thin Red Line and The New World, both of which have been seen as allegories for the corruption of the Garden of Eden, the desecration of the natural world through humanity’s need to fight and conquer. Early scenes of village life in A Hidden Life show entire families working together to thresh fields, tend to livestock, and process grain in their mill. Franz and his wife play with their children, savoring the finer qualities of their contented, isolated existence. But we watch half entranced by the gorgeous imagery, half aware of Nazism’s inevitability. Soon enough, Franz is drafted into the army where he witnesses soldiers clap at footage showing the atrocities of the Third Reich. Unlike his fellow countrymen, he does not vow himself to Hitler; he returns home as a conscientious objector, and the locals label him a turncoat for believing in peace during wartime. St. Radegund falls in line with the Nazi order and develops a sinister fascist undercurrent. It takes no time at all for the villagers opposed to Hitler to become “used to it,” while their mayor speaks out against immigrants, and the gaiety of the village festivals descends into vitriolic, nationalistic tirades that echo Hitlerism. Indeed, Franz’s beliefs present a fissure between himself and the townspeople, including his wife. “They are enemies, but you are a traitor,” he’s told, and his refusal to budge on the issues is deemed “an act of madness.” But Franz asks in his voiceover, “Don’t they know evil when they see it?” It’s a question whose relevance cannot help but reverberate throughout the film and follows us out into the world after it’s over.

Malick’s idea of faith and spirituality comes from within, not church doctrine, as does the strength of his protagonist. Over the three-hour film, everyone around Franz abandons him for his moral decision, until he is anguished and alone with only his principles and soul-searching to guide him. He tells his wife, “We have to stand up to evil,” but she refuses to speak to him because of what his choice means for their family. He speaks with a local bishop (Michael Nyqvist, in his final role), who implores Franz to accept the times. But Franz comes to recognize that Christianity creates followers, not fighters. Malick sees how Christian philosophy sometimes contradicts the reality of the church, which historically aligns itself or conveniently refuses to have an opinion about the cruelly dominant powers of the time, if only to ensure its survival, regardless of who’s in charge. And so, Franz gives up on the church and finds an inner fortitude that inspires. His convictions lead to his imprisonment when, after a trial, he refuses to sign a document that would both represent his loyalty to Hitler and save him. Inside the brick walls of his prison, a sharp contrast to the green pastoral surroundings of St. Radegund, Nazi guards beat him for his refusal to comply. More than one official promises that no one will remember him—a claim disproved by both the film itself and Pope Benedict XVI’s declaration of Franz Jägerstätter’s martyrdom in 2007. And though it’s tempting to draw a parallel between Franz and Christ, he’s less a Christ-like figure dying for the sins of those complicit with Nazism than a rare example of someone unwavering in his conviction. Survival is less important than the “rush” of personal enlightenment that follows his absolute commitment to what he knows is right.

Malick’s idea of faith and spirituality comes from within, not church doctrine, as does the strength of his protagonist. Over the three-hour film, everyone around Franz abandons him for his moral decision, until he is anguished and alone with only his principles and soul-searching to guide him. He tells his wife, “We have to stand up to evil,” but she refuses to speak to him because of what his choice means for their family. He speaks with a local bishop (Michael Nyqvist, in his final role), who implores Franz to accept the times. But Franz comes to recognize that Christianity creates followers, not fighters. Malick sees how Christian philosophy sometimes contradicts the reality of the church, which historically aligns itself or conveniently refuses to have an opinion about the cruelly dominant powers of the time, if only to ensure its survival, regardless of who’s in charge. And so, Franz gives up on the church and finds an inner fortitude that inspires. His convictions lead to his imprisonment when, after a trial, he refuses to sign a document that would both represent his loyalty to Hitler and save him. Inside the brick walls of his prison, a sharp contrast to the green pastoral surroundings of St. Radegund, Nazi guards beat him for his refusal to comply. More than one official promises that no one will remember him—a claim disproved by both the film itself and Pope Benedict XVI’s declaration of Franz Jägerstätter’s martyrdom in 2007. And though it’s tempting to draw a parallel between Franz and Christ, he’s less a Christ-like figure dying for the sins of those complicit with Nazism than a rare example of someone unwavering in his conviction. Survival is less important than the “rush” of personal enlightenment that follows his absolute commitment to what he knows is right.

On the surface, A Hidden Life rings in aesthetic harmony with Malick’s last three films, as Widmer’s camera employs the typical wide-angle lenses and roaming of Lubezki’s images (taken by Widmer, Lubezki’s camera operator). But along with the use of archival footage of the time, Malick experiments with form in unexpected ways. At the moment when Franz receives a notice that he will be put on trial, the camera adopts sharp, agitated movements to reflect the tone of the scene. A sequence of prison guards beating Franz is even more unsettling because it’s filmed from the victim’s POV. These choices feel lively because the seasoned Malick viewer would never expect such a shot, but also because Malick allows form to follow function, as opposed to the subject matter merely passing through his artistic filter. Structurally, A Hidden Life is Malick’s most coherent film since The New World, as the team of editors, who have tinkered with the footage for years after the shoot completed in 2017, create a precise delineation between his occasional flashbacks and his present-day scenes. Elsewhere, the voiceover and dialogue in English is contrasted by the Nazis who speak in German, whereas, when Nazis and the infighting villagers speak, they have no accompanying subtitles—none are needed to grasp the palpable feeling of hatred from their body language. It is a distinct choice on Malick’s part to whom he chooses to give a voice.

Again and again, the villagers and Nazis ask Franz, “Do you think what you’re doing will change anything? Do you think you’ll make a difference?” When a Nazi commander (Bruno Ganz, another final role) makes one last appeal and asks, “Do you have a right to do this?” Franz can only answer in a way that would make Polonius proud: “Do I have the right not to?” Malick avoids aggrandizing Franz’s choice into that of a figure who welcomes martyrdom for the greater good and leaves behind a legacy of devout followers. His choice is inward and true only to himself, regardless of the agony and heartbreak it causes his wife—who is spit upon and insulted in their village. Though he searches for strength from God in prison (“Lord, you do nothing”), his decision leads him to a transcendent freedom in his certainty. For the viewer, it is a moral revelation. “If our leaders are not good,” Franz ponders, “if they’re evil, what does one do?” Some shrug and hope it will all turn out for the best. In a scene between Franz and a mural painter, the artist admits that he hopes to give joy to churchgoers with his representations of a pleasant Christ in Heaven with his disciples. Fear has prevented the painter from acknowledging the truth, and a fantasy is easier than the ugliness of the crucifixion. Franz at least hopes for the truth, whereas those good Nazis in St. Radegund have taken the easier route.

A film that subjects its protagonist to the same question again and again, to which he has the same answer, A Hidden Life has a repetitive but urgent quality, as Franz endures interrogations from Nazi officers (including Matthias Schoenaerts in one scene), lawyers, and his wife. When he finally faces an executioner, Franz enters an unearthly room of theatrical black curtains, like a stage, where he is confronted by ghoulish figures, as if in his final moments he is subjected to the last temptation. It’s a testament to Diehl’s incredible, impassioned performance and Malick’s command of the spiritual stakes that the viewer remains committed to Franz’s decision—we hope he will not waver, and we believe it would be worse if he were to suddenly abandon his resolve. We watch his final scenes with dreadful anticipation, even as we mourn the reality of his faithful choice. Regardless of this energy and emotional reach, the film’s measured pace will produce the usual walkouts and watch-checking among less patient moviegoers, much to the chagrin of those of us experiencing something beyond grasp. Consider it a consolation that A Hidden Life remains hopeful about the future and purity of Nature, despite acknowledging the weight of atrocity in World War II. A few final scenes offer Franziska’s reprieve from the cruelty of the radicalized villagers as she and her daughters enjoy the small things, such as leaping into fresh hay. All is not lost. The world still has beauty in it, and it will continue to heal. Somehow, after all this, there’s a sense of Nature’s indifference to humanity. Looking out at the sublime mountains and verdant hills, we feel that if humanity wiped itself out tomorrow, the planet would eventually set itself right.

A film that subjects its protagonist to the same question again and again, to which he has the same answer, A Hidden Life has a repetitive but urgent quality, as Franz endures interrogations from Nazi officers (including Matthias Schoenaerts in one scene), lawyers, and his wife. When he finally faces an executioner, Franz enters an unearthly room of theatrical black curtains, like a stage, where he is confronted by ghoulish figures, as if in his final moments he is subjected to the last temptation. It’s a testament to Diehl’s incredible, impassioned performance and Malick’s command of the spiritual stakes that the viewer remains committed to Franz’s decision—we hope he will not waver, and we believe it would be worse if he were to suddenly abandon his resolve. We watch his final scenes with dreadful anticipation, even as we mourn the reality of his faithful choice. Regardless of this energy and emotional reach, the film’s measured pace will produce the usual walkouts and watch-checking among less patient moviegoers, much to the chagrin of those of us experiencing something beyond grasp. Consider it a consolation that A Hidden Life remains hopeful about the future and purity of Nature, despite acknowledging the weight of atrocity in World War II. A few final scenes offer Franziska’s reprieve from the cruelty of the radicalized villagers as she and her daughters enjoy the small things, such as leaping into fresh hay. All is not lost. The world still has beauty in it, and it will continue to heal. Somehow, after all this, there’s a sense of Nature’s indifference to humanity. Looking out at the sublime mountains and verdant hills, we feel that if humanity wiped itself out tomorrow, the planet would eventually set itself right.

In the closing passage, Malick quotes the source of his title, the novel Middlemarch, written by Mary Anne Evans under the pen name George Eliot: “For the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” Though A Hidden Life has the potential to soapbox or make grand statements about modern-day fascism or the hypocrisy of the religious right, it considers the personal consequence of the individual and the importance of one following their beliefs, even if their choices will not have an immediate consequence on the world or history. Even so, it’s difficult to watch the film and not believe that Malick is making a statement through Franz Jägerstätter’s story. When many so-called Christian groups act out against others, following political ideas rather than those of their faith, Franz teaches us to be the anvil, not the hammer. “Better to suffer injustice than to do it,” he says at one point. Ultimately, Malick asks the viewer to commit to the process of searching oneself and to have faith in our innermost beliefs, accepting that the unknowable quality of faith strengthens, not weakens. It’s a notion encapsulated in the image of a blindfolded Franz playing hide-and-seek with his family on a grassy hill, as they use a wooden spoon and a metal cup to give a hint of their whereabouts—a simple, beautiful metaphor for the difficulty in locating that faint sound of spiritual conscience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review