A Hero

By Brian Eggert |

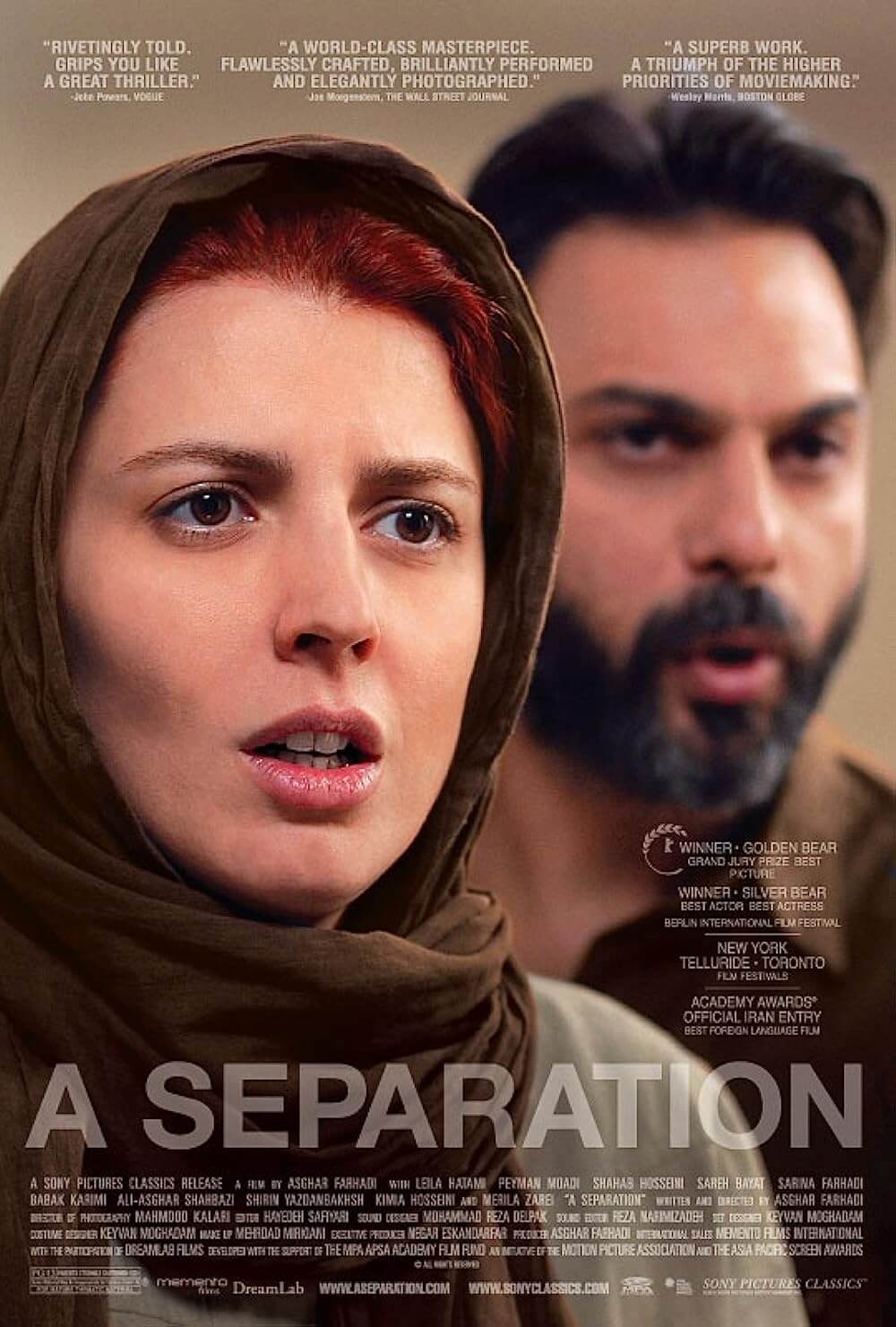

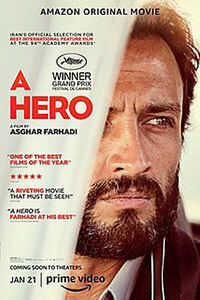

Nothing is fair in the cinema of Asghar Farhadi, and no good deed goes unpunished. The Iranian director of A Separation (2011) explores the complex motivations of his beleaguered protagonist in his latest moral puzzle box, A Hero. The story, set in the Iranian city of Shiraz, follows a man named Rahim, played by Amir Jadidi. Rahim has spent the last three years in debtors’ prison after borrowing money from a creditor to start a business, only to have his partner take their capital and run. While on a brief leave from prison, he returns home to visit his sister, her family, and his son from a previous marriage. When he sees his new lady friend, Farkhondeh (Sahar Goldoost), who he plans to marry, Rahim learns that she found a bag filled with 17 gold coins. They hope to use the coins to pay off his debt and secure his release from prison. When it turns out not to be enough, he takes it as a sign and resolves to find the owner. Whatever his motivations, his Good Samaritanism becomes an inspiration for his prison’s PR man and community leaders to use him as a heroic example to others. But when his creditor and potential employer begin asking questions about the particulars of what happened, the purity of Rahim’s intentions becomes skewed.

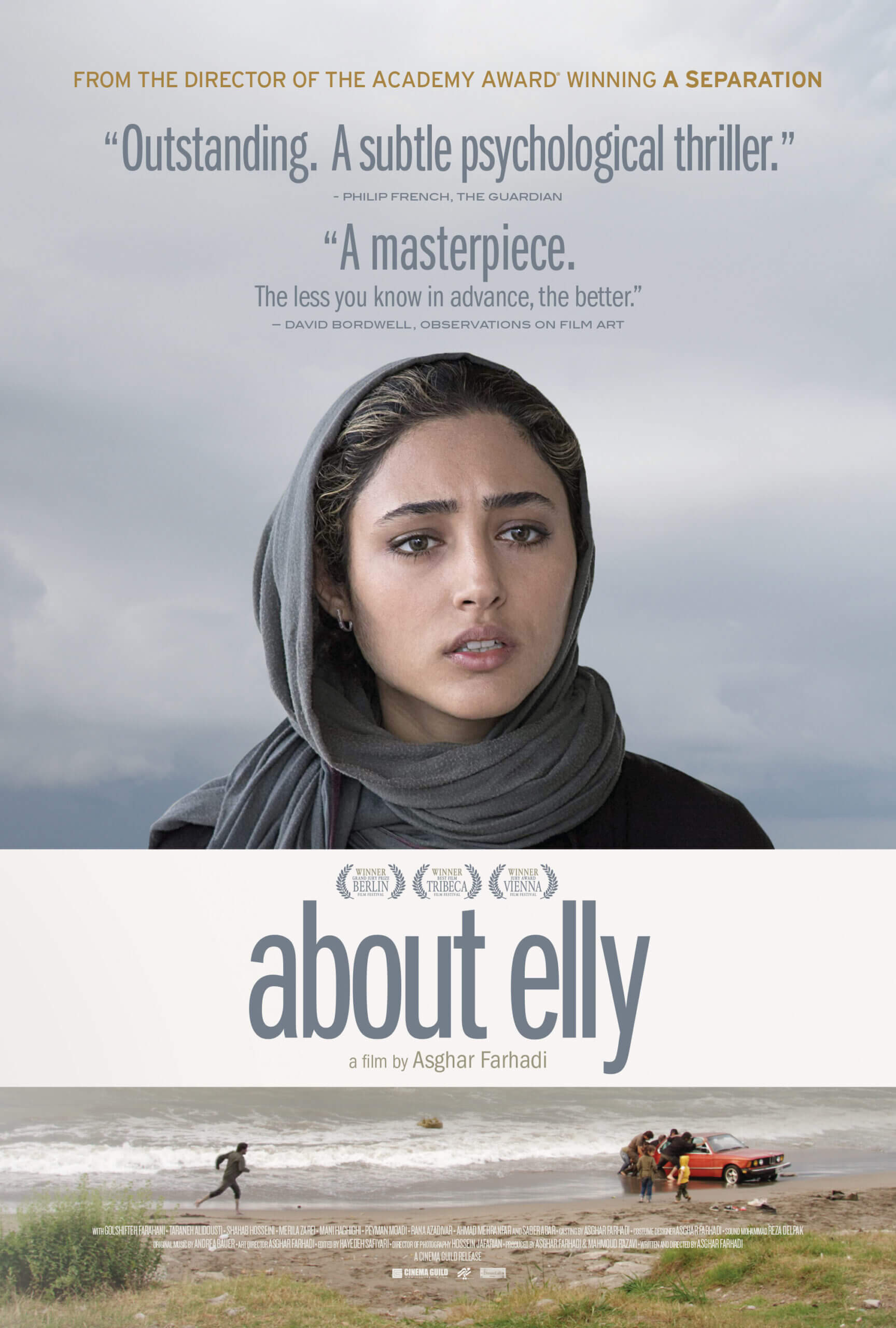

Farhadi makes high drama out of otherwise simple conflicts, which inevitably unravel into something far more nuanced and complicated than they initially appear. The director challenges viewers who like easy answers or clear ethical codes by introducing snags into straightforward situations. But compared to his other work, A Hero features lower stakes. There’s nothing like the disappearance or death from About Elly (2009), nor an elaborate kidnapping scheme like the one in his underrated Spanish-language feature, Everybody Knows (2018). Even the decibel level plays at a relatively even keel in A Hero, as though the story resolves to plug along without snapping the viewer out of quiet involvement. The film has almost no musical score, leaving each scene to speak for itself. Farhadi’s dramaturgy has been composed for maximum immersion, delivering plainly shot scenes of situational immediacy. Jadidi’s performance, too, is carefully measured. Yet, at least next to his earlier films, the intensity level operates at about half tilt.

Regardless, Farhadi remains a master of crafting scenarios that escalate with unbearable tension. If the nonpayment of credit seems like a minor offense for viewers fortunate enough to live in a country without a debtors’ prison, the triviality of Rahim’s misdeeds heightens the desperate circumstances in crucial ways. Even if the worst possible outcome of Rahim’s predicament is that he returns to prison, it’s a consequence that feels urgently avoidable, if only things would go his way. But, of course, they do not. After his sister turns over the bag to its owner, who mysteriously disappears, Rahim is celebrated on social media for setting a “beautiful” and “noble” example. A local charity that helps prisoners raises money on his behalf, hoping to convince his creditor and former brother-in-law, Bahram (Mohsen Tanabandeh), to forgive the debt that landed him in prison. But Bahram sees Rahim from another angle—Bahram talks of Rahim’s past dealings and a pattern of untrustworthy behavior, lending a new dimension to the situation. He also expects to receive the money Rahim borrowed from him—in total, not a settlement. Farhadi makes the intelligent choice to portray Bahram as stubborn, sure, but also practical in his demands. If you had lent 150 million tomans to a relative, wouldn’t you want it back?

Bahram also raises the film’s most essential question: Why is everyone congratulating Rahim for a basic act of decency? Shouldn’t everyone be expected to do the right thing? “One should prioritize good deeds over personal ambition,” Bahram explains, in the character’s grumbly way. Instead, Rahim finds himself entrenched in an inescapable bureaucracy that compels him to tell white lies to move forward. Though, when exposed, each lie is treated as a capital crime in the court of public opinion. In his indirect way, Farhadi cuts into a characteristic of Iranian society—though, these factors prove universal as well—that values the appearance of goodness, even if the reality isn’t as savory as it seems. He portrays how the public reacts, to polarizing effect, to the latest rumor or video relating to Rahim’s case. At the same time, he shows various institutions trying to manipulate the press and social media, using a marketable story to influence people for their own benefit. But if the optics don’t play in the institutions’ favor, they will make him into a pariah.

No classical heroes exist in Farhadi’s ironically titled film, and no one remains unspoiled by moral compromises. If Rahim ever feels heroic, it’s in a scene that causes him to break from his subdued mannerisms and react with aggression to protect his stuttering son—when he’s compelled as a father to keep his boy out of the media circus, even if it might help his cause. But Farhadi isn’t condemning Rahim for his behavior. If there are no heroes, there are no villains either. Instead, the filmmaker shows his characters ensnared in an inescapable web of social interaction, which extends well beyond the borders of Iranian culture. Farhadi questions the value of laws, organizations, and behaviors that expect moral absolutes when no such thing exists in the world. A Hero shows how people often have selfish motivations for their good deeds and how they regularly reframe the truth to shine a better light on themselves. Occasionally they slip up, and even though that’s a universal truth about human beings, it’s rarely treated with the appropriate understanding or empathy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review