A Haunting in Venice

By Brian Eggert |

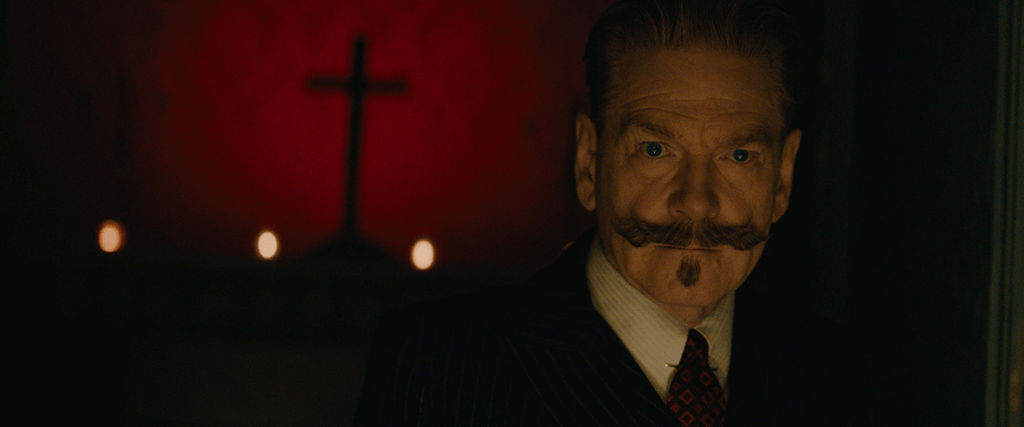

Spooky season begins early with Kenneth Branagh’s latest foray into Agatha Christie’s literary detective, Hercule Poirot. A Haunting in Venice combines the mystery author’s whodunit template with supernatural horror, drawing its ghostly mood from its Halloween setting amid Venetian canals and masks. Based on one of Christie’s later books, Hallowe’en Party, published in 1969, the film contains a hair-raising atmosphere and creepy undertones. “In Venice, we say, ‘Every house is haunted or cursed,’” observes one character. Indeed, the film’s Floating City boasts a haunted orphanage with a disturbing past, complete with the spirits of children trapped and left to die years earlier. Outside, thunderstorms and lightning rage; inside, shadows and candlelight, even a few jump-scares, give the surroundings a sinister edge. A séance early in the proceedings raises questions about specters on the premises, and a murder requires the mustachioed Belgian sleuth to come out of retirement to solve it. All the while, Branagh energizes the Christie mold with a horror-inflected current that activates the material and playfully experiments with both genres.

Best of all, unlike Branagh’s previous adaptations, Murder on the Orient Express (2017) and Death on the Nile (2022), there’s no history of book-to-screen versions of this story, aside from a few minor televised examples. Whereas watching the director’s first two Poirot movies felt like seeing a particularly lavish and star-studded revival of well-known scenarios, most viewers unfamiliar with Christie’s books won’t enter already knowing the culprit. This does wonders to immerse us in the movie. Moreover, the script by Michael Green, the sole screenwriter in Branagh’s Poirot series, loosely adapts the book. For instance, the source material takes place in an English village, and further, the only plot details that Green and Branagh carry over seem to be the logline: Hercule Poirot investigates a murder at a Halloween party. The rest is cleverly invented with a new setting and different victims—perhaps even taking influence from Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973) in deploying psychic visions, apparitions, and murder in the so-called City of Masks.

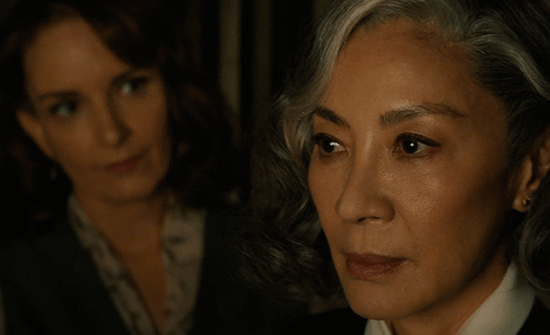

Having retired but looking decidedly less gray than his earlier appearances, Branagh’s Poirot now lives a quiet (aside from the occasional bad omen nightmare) and reclusive life in Venice. His solitude is interrupted by Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey, not quite immersed in her Rosalind Russell routine), a murder mystery author whose popularity helped make a name for the detective and whose fiction was inspired by his mysteries. She invites Poirot to debunk a reportedly “unholy” medium, Joyce Reynolds (Michelle Yeoh), who plans a séance to speak with the late teen daughter of Rowena Drake (Kelly Reilly), owner of the haunted orphanage mentioned above. Ever the realist driven by facts and evidence, Poirot has no faith in such spiritualism. He watches Joyce’s performance, doubtful of its authenticity or her possession by the dead teen; though, Joyce insists that she and Poirot have more in common than he might think. They both “speak to” the dead in distinct ways, Poirot through clues and reasoning, Joyce through her sixth sense, if she’s to be believed. Yeoh, the recent Oscar winner, delivers a terrific performance, and her brief screentime is scene-stealing, yet her presence is powerful enough to instill doubt in Poirot about his worldview.

Eventually, a murder occurs on the premises, requiring Poirot to lock everyone inside the tormented shelter on a dark and stormy night while he interviews them, with Ariadne by his side. The suspects, as usual, include everyone, even Ariadne, the grieving Rowena, and Poirot’s ex-cop bodyguard (Riccardo Scamarcio). Could the killer be Dr. Leslie Ferrier (Jamie Dornan), whose nervous behavior and pill-popping suggest his instability? Doubtful that it’s Ferrier’s young boy, Leopold (Jude Hill)—but then again, the child seems uncannily mature for his age. Or, maybe it’s the orphanage’s caretaker, Olga (Camille Cottin); the dead daughter’s former fiancé Maxime (Kyle Allen), who holds a grudge against the possessive Rowena; or Joyce’s two Hungarian assistants (Ali Khan, Emma Laird), who dream of moving to Missouri. With Poirot experiencing strange whispers and images of wraithlike children, the detective’s usual routine of interviewing everyone and then gathering them together for the big reveal is somewhat disrupted, but not enough to stop him from sniffing out the culprit.

Eventually, a murder occurs on the premises, requiring Poirot to lock everyone inside the tormented shelter on a dark and stormy night while he interviews them, with Ariadne by his side. The suspects, as usual, include everyone, even Ariadne, the grieving Rowena, and Poirot’s ex-cop bodyguard (Riccardo Scamarcio). Could the killer be Dr. Leslie Ferrier (Jamie Dornan), whose nervous behavior and pill-popping suggest his instability? Doubtful that it’s Ferrier’s young boy, Leopold (Jude Hill)—but then again, the child seems uncannily mature for his age. Or, maybe it’s the orphanage’s caretaker, Olga (Camille Cottin); the dead daughter’s former fiancé Maxime (Kyle Allen), who holds a grudge against the possessive Rowena; or Joyce’s two Hungarian assistants (Ali Khan, Emma Laird), who dream of moving to Missouri. With Poirot experiencing strange whispers and images of wraithlike children, the detective’s usual routine of interviewing everyone and then gathering them together for the big reveal is somewhat disrupted, but not enough to stop him from sniffing out the culprit.

A Haunting in Venice is arguably the best-looking of Branagh’s three Poirot pictures thus far, with returning cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos shooting exterior footage of stunning Venice rooftops, sculptures, bridges, and walkways. Likewise, the interiors created in Pinewood Studios, with rich and textured production design by John Paul Kelly, look timeworn and eerie. And fortunately, the production never feels bogged down by CGI backdrops or artificial-looking scenes, as its predecessors often did. Zambarloukos’ wide, arch, and cockeyed angles prove compellingly otherworldly, even when employing a body-mounted camera for a disorienting sequence. The chiaroscuro lighting, cutting the darkness with lanterns or candlelight, imbues the material with bold contrasts and highlights worthy of Caravaggio. With the film’s gothic beauty recalling the work of Guillermo del Toro on Crimson Peak (2015), the only downfall to the mise-en-scène is Branagh’s conventional deployment of flashy ghosts to jolt the viewer.

At the same time, Branagh appears delighted by playing in the horror genre sandbox, and he has studied his antecedents well. He lands a couple of jarring jump-scares with a screeching parrot and a boom on the soundtrack, similar to countless supernatural horror yarns today. But the spiritual element also feeds a theme that questions Poirot’s belief system and whether he believes there’s more to the universe than cold, hard facts. It’s a strain that doesn’t feel appropriate for the character, but Branagh doesn’t mind taking liberties and allowing the character to grow. However, some of Branagh’s choices feel unfitting. For instance, in a rather unbelievable scene, the movie finds Poirot alone and tempted to bob for apples. Would the fussy, superficial, and germaphobic detective really risk undoing his ornate and carefully maintained mustache to stick his head into a bowl of water and fruit, which dozens of others had done earlier in the night (yuck)?

But no matter. A Haunting in Venice will surely please moviegoers looking for a whodunit or those ready to start their horror gorge early this year (as I am). The whole notion of a ghostly murder mystery in waterlogged surroundings brings to mind Robert Zemeckis’ What Lies Beneath (2000), another film whose predictable situations feel enlivened by the slick direction, committed cast, and themes of buried secrets and trauma. A Haunting in Venice also economizes its screentime, delivering, at 103 minutes, Branagh’s shortest and most efficient Poirot story yet. Each character gets their moment under the spotlight, while Poirot remains mostly unchanging but no less dynamic or entertaining in Branagh’s hands, despite his dependable nature. The story never overstays its welcome, and the milieu of Venetian masks, Halloween costumes, and supernatural horror becomes a worthy, even inspired innovation on Christie’s usual agenda.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review