A Fantastic Fear of Everything

By Brian Eggert |

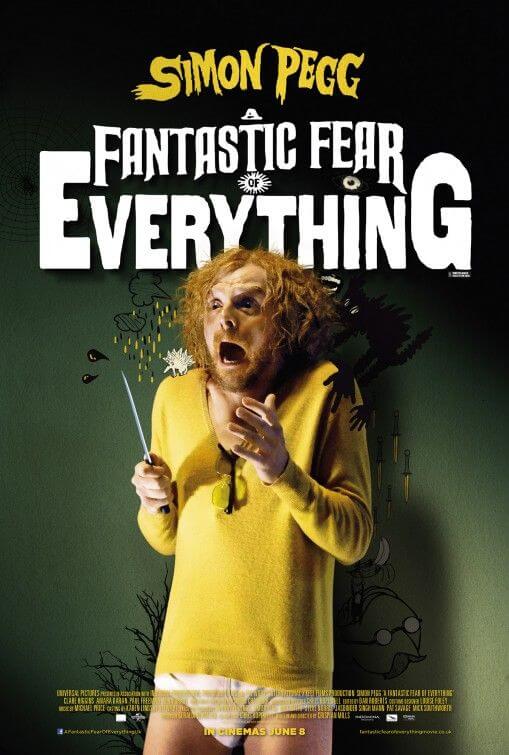

If former Kula Shaker frontman Crispian Mills asked me to star in his filmmaking debut, I suppose being starstruck, I would agree too. But for Simon Pegg, star of Mills’ first writer-director project, A Fantastic Fear of Everything, it’s another underwhelming release not unlike the starrer’s Burke & Hare, Paul, or Run, Fatboy, Run. This morbid and nightmarish comedy features a wide range of expressive scenes for the unhinged Pegg to explore in over-the-top comic effect, the actor’s physical comedy muscles flexed to full effect. But the material, rooted in the ravings and delusions of a paranoid and introverted author, never quite clicks in the darkly funny way it’s meant to. Although Pegg’s performance and several individual scenes show tenacity and even eke out the occasional chuckle, the overall work feels misguided and tonally scatterbrained. Produced by Pinewood Studios and released in the U.K. in 2012, this low-budget title was imported to the U.S. by Universal Studios and Indomina Releasing for a limited theatrical and heavy VOD debut.

Based in part on the short story Paranoia in the Launderette by Bruce Robinson (director of The Rum Diary), the story begins with the tone of a murder mystery told in the first person by Jack (Pegg), a children’s book author who’s trying to break into screenwriting. Jack’s script called “Decades of Death” is about Victorian Age serial killers, and the subject has consumed him; gruesome photographs and accounts of grisly murder adorn the walls in his apartment, located in London’s dodgy East End. But as Jack’s paranoia becomes apparent and our grating protagonist begins reacting ludicrously afraid of shadows and the telephone ringing, the comic irony plays out to absurd degrees. Since he was a boy, Jack has been stricken with a debilitating fear of the world, specifically the launderette (or laundromat to Americans). As a result, he’s perpetually garbed in soiled clothes and surrounded by filth.

Frazzled and grubby and always in an exaggerated state, Jack’s obsessions consume him, and much of the film’s first half involves Jack alone in his apartment with his suspicious thoughts. He’s forced to address his fears and leave his apartment in the second half, when his literary agent (Clare Higgins) tells him a film studio executive is interested in Jack’s script and wants to meet him. The remainder of the story involves Jack preparing for his meeting, which requires him to wash his grubby clothing—first in his sink and oven, and when that doesn’t work, at the nearby launderette. Laundry is something which apparently this character has never done before. When not asking yourself how Jack survived this long without washing his clothes or leaving the house, the viewer experiences mixed feelings of annoyance and admiration toward this rollercoaster of tonal shifts.

Mills is joined by co-director Chris Hopewell, helmer of music videos for Radiohead ( “There There”) and The Killers (“Smile Like You Mean It”). Collectively, the two are guilty of too much evident admiration for the likes of Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam; but not the genius-level Burton and Gilliam, only the uncomfortable and graceless versions of their work (see Dark Shadows or Tideland). Atmospheric scenes of macabre humor are offset by bonkers turns of surrealism, stop-motion animation, and madhouse logic. The most creative scenes involve effective, hilariously moody lighting and ominous shadows in Jack’s disgusting apartment. Later, between Jack releasing tension through segments of gangster rap and his encounter with local killer the “Hanoi Handshake,” the viewer is torn between the admirable high-energy presentation and how incongruous it all seems when reflected upon as a whole.

Another music video alum, Simon Chaudoir’s sharp lensing gives A Fantastic Fear of Everything a distinct look, as does Hopewell’s production design. Standing out is the aforementioned stop-motion animation sequence set around Jack’s kiddie character “Harold the Hedgehog,” which alone could make a great short film. Mills and Hopewell strive for something quirky and weird, their influences obvious, and their visual presentation ever watchable. As for Pegg, he certainly won’t be accused of under-acting or not giving what is largely a solo performance his all. But the narrative amounts to a frenzied form of therapy for an unlikable, overly anxious character whose advance jumpiness has perpetuated the film’s increasingly improbable, ever more exasperating situations. The filmmakers’ wildly uncontrolled tonality, however, represents a complete failure of purpose, as though the film was conceived one piece at a time, resulting in a mish-mashed assembly of ideas and inspired visual touches that are intriguing if incompatible.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review