A Different Man

By Brian Eggert |

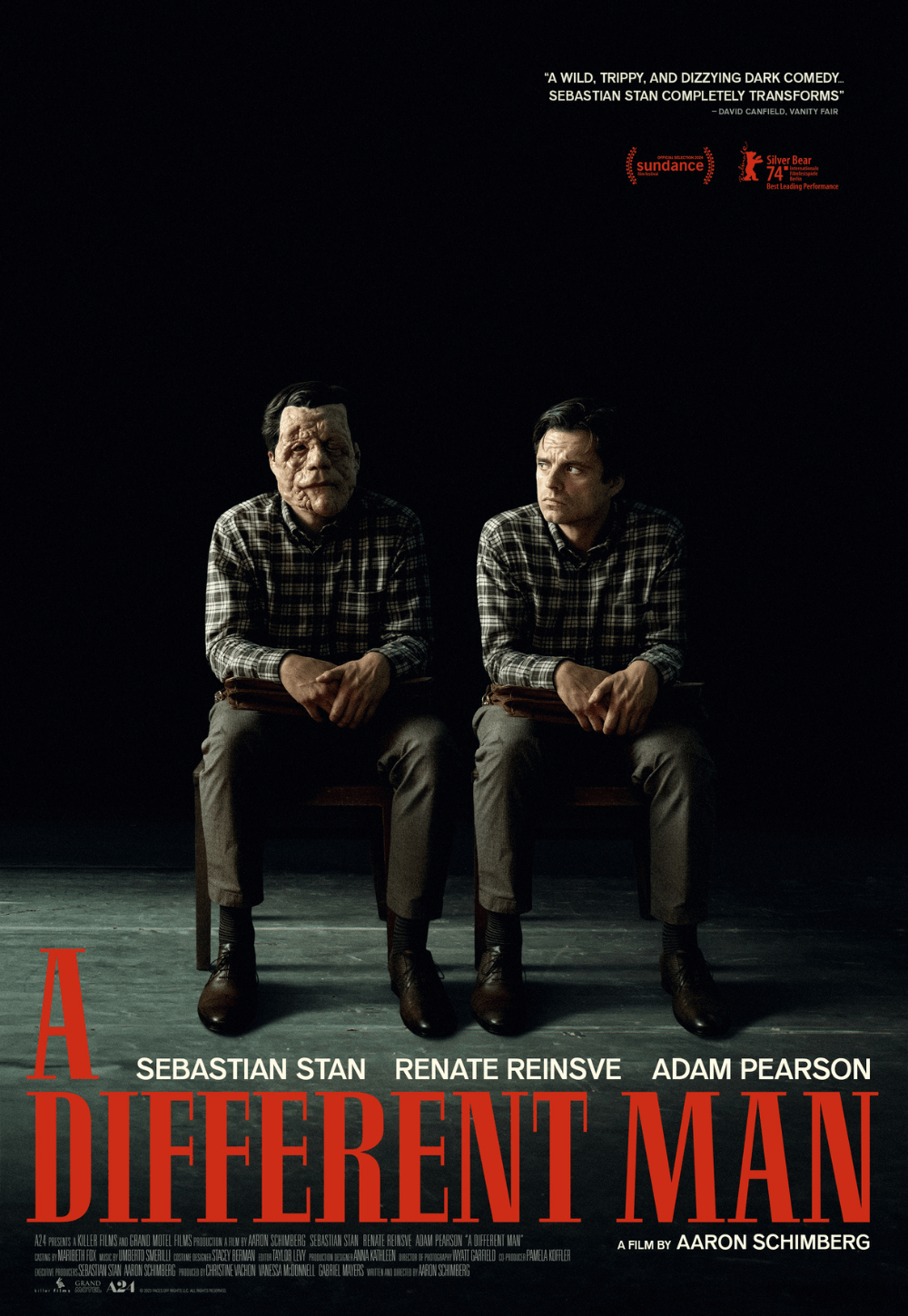

Early in Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man, Edward sits on a windowsill, stroking a cat that, until recently, belonged to the man down the hall. This same neighbor hanged himself despite, as Edward noticed, having an attractive girlfriend. The thought is baffling to Edward (an excellent Sebastian Stan), whose sense of isolation, he believes, stems from his neurofibromatosis. The genetic disorder causes benign tumors to grow around his face, swelling at random and distorting his appearance. Edward looks down in the street and sees the ambulance, sirens blaring, as paramedics load his neighbor’s body into the back. Then, an ice cream truck approaches, its jingle competing with the sirens, but there’s not enough room to squeeze by. Somehow, this scene anticipates everything to come for Edward. When medical innovation allows him to reverse his condition, he eventually sheds his exterior to look like Stan, a version of himself that has every superficial physical characteristic a person could want. But his counterpart, Oswald, played by Adam Pearson, thrives in defiance of his neurofibromatosis, much to Edward’s maddened frustration. Through his neurotic protagonist, Schimberg thoughtfully mines existential questions of identity with touches of surreal and darkly comic introspection, offering a jazz-like riff on complex emotions inside an inventive and cleverly self-referential narrative structure.

A Different Man complements and expands upon themes and modes found in Schimberg’s last film, 2018’s Chained for Life, a backstage drama about a movie shoot with a supporting cast of disabled actors, headed by Pearson. Like that film, his latest weighs the ethics of representation and how even well-meaning inclusiveness can be exploitative. Similar to films such as Freaks (1932), Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), and The Elephant Man (1980), Schimberg’s work yearns for empathy. But he also considers the uneasy dynamics of such actors and characters appearing onscreen. Even as ableist filmmakers endeavor to avoid negative associations, how does the audience see the actors? Have they been chosen because they look this way, and what are the implications of art imitating life for them? Schimberg was born with a cleft palate, and his 2009 short film Late Spring: Regrets for Our Youth detailed his attempts to have it fixed. He asks these questions from a place of experience, acknowledging there are no easy answers, not even when it comes to talking about these films. Writing in Talkhouse, the director admits that he and Pearson prefer the word disfigured over the usual alternatives: disabled, afflicted, deformed, abnormal, etc. While some call these conditions facially different, Schimberg and Pearson find the term inappropriate, given that outside of identical twins no two human faces look the same.

Schimberg’s approach establishes mind-bending connections between life and mimesis, deploying self-reflexive parallels between characters that underscore the complicated stakes. But A Different Man might also be reduced to something Edward’s apartment building super tells him, attributing the quote to Lady Gaga; however, it’s more reasonably attributable to Buddha: “All unhappiness in life comes from not accepting what is.” The film begins with a portrait of Edward, featuring Stan under a convincing prosthetic by makeup artist Mike Marino that furthers the actor’s recent chameleon-like quality in roles from I, Tonya (2017) to FX’s Pam & Tommy miniseries. With a nervous energy compared to early Woody Allen types, Edward visits the doctor’s office and rides the subway, avoiding the gaze of individuals and crowds who stare and smirk at his appearance. Conditioned to think of himself as lesser-than, Edward tends to avoid conflict and allow bad situations to get worse; just look at the leak in his ceiling that develops from a small drip into a blackened hole from which dead rats drop into his apartment. It’s an apt metaphor for Edward’s sense of self, which continues to rot even after the drastic change in his appearance.

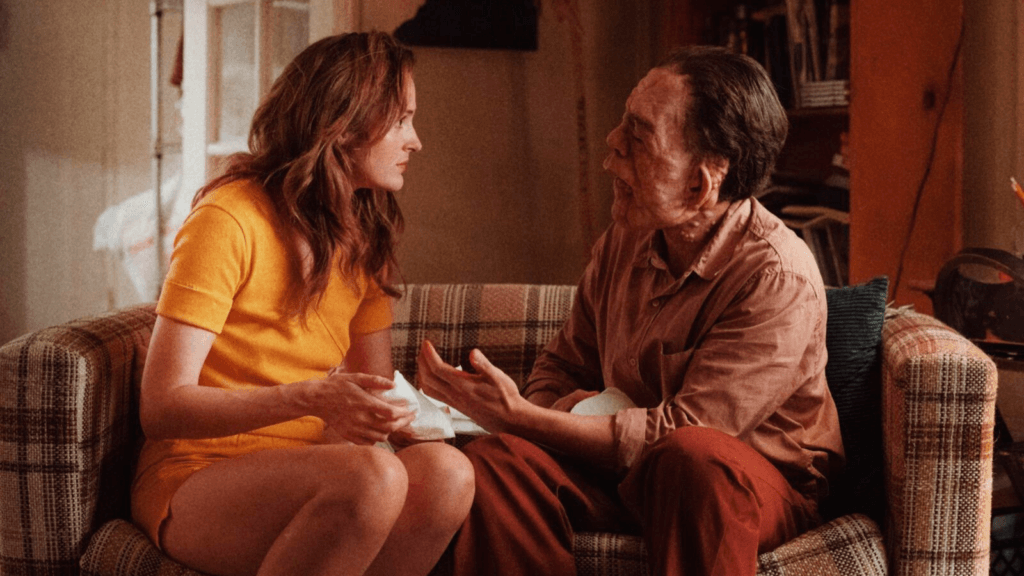

At home, he’s excited to learn a new neighbor, an attractive but self-involved playwright named Ingrid (Renate Reinsve, from The Worst Person in the World, 2021), has moved in next door. Though Ingrid initially gasps at him, she quickly becomes comfortable around Edward, bandaging a wound he sustains chopping vegetables in the kitchen and attempting to clear a distracting blackhead on his nose. Ingrid may seem comely, but she’s quick to hurry out of Edward’s apartment when he gently grasps her hand, prompting the rejected Edward to commit to an experimental drug trial that gradually causes his facial growths to peel away. The situation recalls a reversal of what occurs in David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), complete with scenes in the bathroom mirror and chunks of flesh peeling off with ease. But once his old face melts away, instead of revealing a monster underneath, he’s shown to look like Sebastian Stan and becomes unrecognizable to everyone in his life, his doctor included. Now anonymous, Edward makes an impulsive choice worthy of Tom Ripley: he concocts a story about his suicide and starts a new life as the dully named Guy—an outwardly normal man who lives in an upgraded apartment, beds random women, and sells real estate.

Without troubling the audience about how Guy obtained his new identity, Schimberg’s screenplay has a Kaufmanesque quality, sharing thematic DNA with Being John Malkovich (1999), Synecdoche, New York (2008), Anomalisa (2015), and I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020) as it propels itself deeper into its surreal, metafictional scenario. Sometime later, Guy runs into Ingrid, who’s casting a play she has written called Edward, based on his life. Guy auditions for the titular role without revealing he’s Edward, declaring, “I was born for this.” Wearing a mask of his disfigured face supplied by his former doctor, Guy lands the role and launches into a romance with Ingrid. On stage, he rehearses scenes that Ingrid lifted verbatim from his former life to which she claims authorial credit. “It’s my creation,” she tells him, not realizing that he’s the one person who knows how untrue that statement is. Guy doesn’t dispute this, although the viewer yearns for him to confront Ingrid’s persistent lies about her material and its origins. Her narcissism becomes marked when she proudly declares that she has left a string of clingy men in her wake, all but admitting that she cares little for anyone else but herself. Guy proves just as self-obsessed, albeit from an initially less destructive and more inward-facing place. And the more he acts as Edward in the stage production, the more he realizes how much he still feels like that person, regardless of his change in appearance, but no one treats him the way he expects (pity, revulsion, enhanced empathy) because he looks normal.

Just as he did with Chained for Life’s film-within-a-film structure, Schimberg’s reflective dramatics intermingle real-life and stage performances, creating a deliriously crafty series of mirrors that reflect how art replaces reality for Edward. Early on, he appears in a corporate video about how able-bodied people should behave around those with physical maladies, but his acting proves wobbly, regardless of his personal experience. As Guy, he performs better in Ingrid’s play behind the mask, but he’s soon upstaged when Oswald arrives at rehearsals, unfazed by his neurofibromatosis and exuding charisma. Whether he’s really as benevolent and considerate as he appears—in addition to being talented in myriad ways—remains in question. Is Guy just paranoid, or does Oswald keep intruding on his life in a manipulative attempt to convince Ingrid to cast the genuine article instead? All the while, beneath A Different Man linger those nagging questions about who should play these roles, many of them raised in Chained for Life as well. Is it exploitative to cast someone who’s disfigured to play a similar role? Or should the casting of a character align with the qualities of the performer, based on gender, sexuality, race, or appearance? Isn’t acting the point of acting? Guy knows Edward inside and out—he was and is Edward—but Oswald looks the part. Edward was the part Oswald was born to play.

Of course, Guy finds Oswald’s confidence and success in all matters, personal and professional, profoundly frustrating. He’s everything that Edward couldn’t be, which underscores how Edward’s personal failures were less attributable to his condition than his personality. “Fear is a reaction,” someone tells him. “Courage is a choice.” Oswald has chosen courage, and Pearson is exceptionally charming and slyly diabolical in the role, having come a long way since his somewhat reductive but profound part in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2013). Elsewhere, the mask Edward wears as Guy hides the character’s fear, and Stan has never been better, playing a character who, no matter how he looks, seems uneasy in his skin. Both performances are sensational, with Pearson proving diegetically and otherwise that a person can overcome not fitting into the conventional definitions of beauty. Guy’s trajectory takes a more unexpected and shattering turn in the last third that may seem random, but it only furthers the intricacy of Schimberg’s interest in multifaceted characters.

Set aside Schimberg’s terrific script, the fine-tune performances, and the head-spinning tiers of meaning, A Different Man is also a richly made piece of formal work. Much of the story is captured by cinematographer Wyatt Garfield’s 16mm camerawork, adding a grainy quality to the image that is complemented by Taylor Levy’s alternately patient and urgent editing. Underneath the film’s distinct shifts from Edward to Guy to Guy’s downward spiral, Schimberg relies on Umberto Smerilli’s affecting score, with melancholy clarinets reminiscent of Carter Burwell’s music for so many Kaufman and Coen brothers features. Although Schimberg’s film—his third after Go Down Death (2013) and Chained for Life—may draw comparisons to others’ work, it’s refreshingly not a reference machine or full of obvious allusions to the movies that inspired him. Instead, like one of Kaufman’s or the Coens’ more serious films, A Different Man feels like a self-contained puzzle about a troubled man and his broken selfhood. The closest Schimberg gets to extratextual references are the links to his previous work, which only establishes him as an original voice.

On a basic level, Schimberg shows the debilitating effects of how social conditioning establishes standards of beauty that amplify symmetrical features and condemn deviations. It’s curious that, after their respective runs on the festival circuit, A Different Man should open nationwide on the same day as Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance—both about doubles, both commentaries on the entertainment industry, and both critical of how culture shuns anyone who doesn’t align with its beauty ideals. Like The Substance, Schimberg’s film bears certain similarities to films such as John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966) and countless others about a drastic change in one’s physical appearance supplying an inadequate solution to deeper issues of the mind and self-image. However, beyond its discussion of ableism, the ethics and motivations of casting, and the representation of disfigured persons, there’s an elaborate and tangled interest in character dimension in Schimberg’s film that proves ever more rewarding as it goes, supplying a much-needed antidote to the one-note treatment of characters in Fargeat’s feature. The filmmaker’s brilliant deconstruction of Edward, Ingrid’s play, and the supporting characters become layers in a fascinating onion of a film, each one revealing yet another remarkable layer.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review