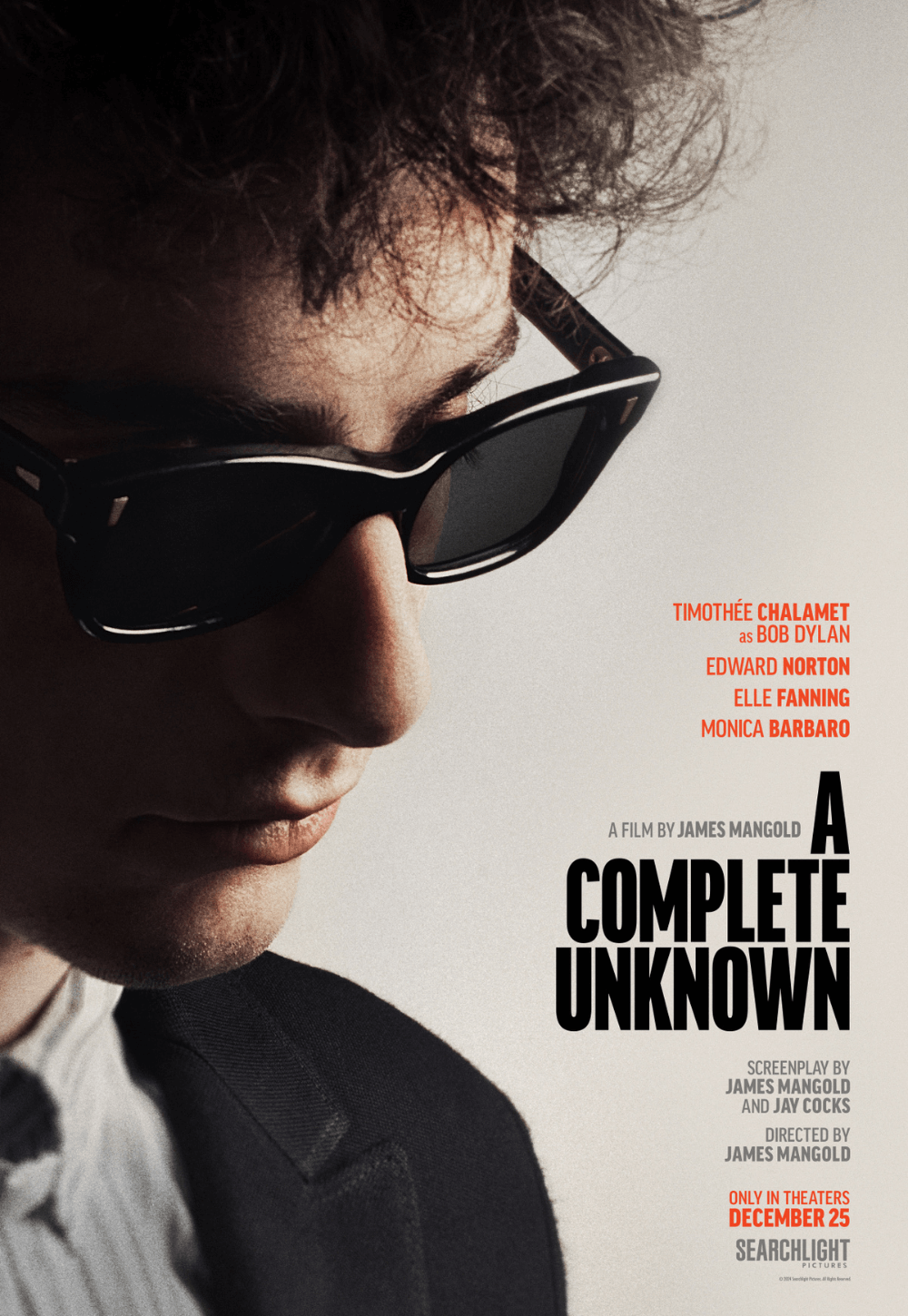

A Complete Unknown

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on December 10. Searchlight Pictures will release A Complete Unknown in theaters on December 25, 2024.

In A Complete Unknown, James Mangold approaches Bob Dylan with the same intelligence and assured direction he applies to each project. The film charts the iconic singer-songwriter’s rise in the 1960s folk music movement, culminating in 1965 with his disruptive leap to electric guitars and rock music at the Newport Folk Festival. Over a half-century later, this may hardly seem monumental given the omnipresence of electric instruments then and now. Still, Mangold’s devotion to the story thoughtfully details the necessary contexts, imparting how the shock of Dylan’s sound rattled the acoustic purity of folk ears and established Dylan’s characteristic nonconformity. Timothée Chalamet’s strong performance as Dylan anchors A Complete Unknown, which dabbles in typical biopic scenes yet avoids overused tropes, using the well-documented episode from the musician’s life as a microcosm of his lifelong mercurial tendencies. A handsome and confidently made production, Mangold takes the tired musician biopic, employs many of its most well-worn clichés, and—much as he did with 2005’s Walk the Line—reminds us that these motifs can still work with the right application of skill.

For Dylan enthusiasts, A Complete Unknown won’t be the first time they’ve seen a movie tackle when he went electric and seemingly betrayed his folk fanbase. Documentarian Murray Lerner first covered the subject in Festival (1967), about folk artists who take the “high road” to embrace tradition, community, activism, and social justice through their music. Decades later in 2007, Lerner returned to the subject with The Other Side of the Mirror: Bob Dylan Live at the Newport Folk Festival. In his exhaustive Dylan documentary, No Direction Home (2005), Martin Scorsese also explored the electric incident. And Todd Haynes dramatized the moment in his masterful I’m Not There (2007), with Cate Blanchett performing as Jude Quinn, a fictionalized version of Dylan who, like the musician, is called a “Judas” for leaving the unplugged sound behind. In the wake of so many memorable representations, it’s worth questioning what another movie could add to the conversation.

Mangold collaborated with screenwriter Jay Cocks to adapt Elijah Wald’s 2015 book, Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. If you’re familiar with the story, their treatment doesn’t shine a light on new aspects but illuminates textures and gradations that transport the viewer to the era. The folk underground, so memorably captured in Joel and Ethan Coen’s Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), is the film’s backdrop. Mangold and his editors (Andrew Buckland and Scott Morris) bring the era to life with long sequences of live performances, lovingly delivered by the cast, who really sing the songs and play the instruments. Chalamet spent years mastering Dylan’s sound, and he’s a convincing imitation. Just as impressive are Edward Norton as Pete Seeger, the kindly father figure who takes Dylan under his wing before the iconoclast abandons him. But the breakout performance belongs to Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez, the kind of portrayal that makes one stop in their tracks.

Dylan arrives in New York in 1961 to meet his idol, Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), who has been hospitalized. While there, he dazzles the attending Seeger with an intimate performance. Seeger then introduces Dylan to his folk music circle around Greenwich Village, where the newcomer earns instant attention for his distinct sound and multifaceted lyrics. At the same time, he launches into a love affair with Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning)—a fictionalized version of his early-career muse, Suze Rotolo. Much like her presence on the cover photo of Dylan’s first album of original songs, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Sylvie/Suze clings to the arm of the capricious performer, whose perpetual lateness, insensitivity, and rejection of any categorization mean every relationship is fleeting. In the film’s most tragic subplot, it takes Sylvie years to realize this, and Fanning captures her heartbreak in devastating, wounded expressions.

Indeed, ever the contrarian and unwilling to be pigeonholed, Dylan can come off like an inconsiderate jerk in his brutal honesty. He tells Baez her singing is “too pretty” and her songs are “like an oil painting in a dental office.” Even so, that doesn’t stop them from sleeping together or Dylan from going on tour with her. A genius songwriter filled with more experience than his age would suggest, Dylan’s talent doesn’t allow for long-lasting relationships. Just as he sings “Times they are a-changin’” with unfathomable relevance to the 1960s, he changes too, refusing to sell out or give his paying audience what they want. As he becomes more assured as Columbia’s top-selling act, he has more freedom to follow his whims. Others resent him for his defiant independence. This culminates at the Newport Folk Festival—whose motto, “From the people, for the people,” implies a particular creative hindrance to an individualist artist. But as Dylan sings, “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more.” He refuses to create for anyone other than himself; that includes his audience and his label. Rather, for him, life is one big carnival train.

Chalamet never entirely disappears into Dylan; speaking through his nose and barely animated lips, his performance is a splendid impersonation, but it’s not an embodiment. There’s an unknowability behind the real Dylan’s eyes, whereas Chalamet clearly communicates whatever’s inside—it’s the reason so many connect with his characters. He’s an open book. Nevertheless, Chalamet and Barbaro deliver stunning, deeply moving vocal harmonies in their stage performances. This is a soundtrack fans should rush to download. As for the other players, Norton deserves awards consideration for his gentle mannerisms and hurt look in the final sequences. Boyd Holbrook also steals his scenes as Johnny Cash. Never mind the strangeness of Mangold directing two films almost 20 years apart, both with superb versions of Cash. Holbrook’s take is less dimensional than Joaquin Phoenix’s, but he plays a force of Nature who compels Dylan to “track some mud on the carpet” and upset people. (He also has the film’s most ridiculous moment when Cash drunkenly offers Dylan some Bugles.) Norbert Leo Butz also does fine work as the frustrated head of the Newport festival; unfortunately, the rise of an icon sidelines his character’s passionate devotion to folk philosophy.

Although A Complete Unknown belongs in the same camp as this year’s Back to Black or Bob Marley: One Love, comparing Mangold’s film to these others reveals how much the writing and technique matter. The script by Mangold and Cocks is excellent, even though it tracks in the usual biographical hallmarks, from recording sessions to scenes where the artist conceives his most iconic song (“Like a Rolling Stone,” the tune that informed this film’s title and others). Only one moment where Chalamet’s head has been superimposed onto Dylan’s at the 1963 March on Washington rings as false and unintentionally funny, like a scene from Forrest Gump (1994). Mangold is a journeyman filmmaker. One may not be able to pick his films out of a lineup by appearance or authorial themes, but his devotion to telling the story in the best possible way enriches his work. His production’s formal credits are pristine, with cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, production designer François Audouy, and costume designer Arianne Phillips all doing incredible work.

Poised for awards season—given its Christmas Day release, saturated marketing campaign, and widespread distribution of the soundtrack—A Complete Unknown is precisely the sort of middlebrow fare that voters love. Every performance is well-honed, the technical presentation has few kinks, and the script eschews both pandering and pretension. But it also breaks no boundaries. Dylan might agree that boundary-pushing is a sign of true, uncompromising art. Even so, the film will surely score nominations and probably awards. And while my tone now risks damning the result with faint praise, let me clarify: This is a sturdy, wonderfully assembled film that, if trusted to another filmmaker, one without the deft craftsmanship that elevates Mangold’s work, may have been standard to the point of banality. Instead, watching the film, any thoughts of the tired musician biopic genre fade, leaving several marvelous performances and even more iconic songs ringing in the ears. If A Complete Unknown breaks no new ground, it reinforces how the work of talented filmmakers can renew any overworn genre.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review