A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood

By Brian Eggert |

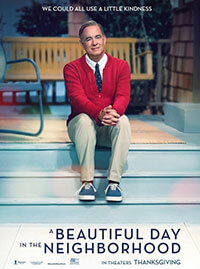

In Marielle Heller’s A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Tom Hanks plays public television icon Fred Rogers, the genial host of the PBS children’s program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and Hanks is the perfect choice for the role. Some moviegoers will doubtless be unfamiliar with Rogers’ deceptively simple show, with its hand-puppets and journeys into the kingdom of Make-Believe. Or maybe you had cable, and so you grew up watching Nickelodeon or the Disney Channel, in which case the film’s attempts at nostalgia may be lost on you. If you’re not familiar with Rogers, at least you know Hanks, the genial everyman actor often compared to Jimmy Stewart. Hanks has made a career out of playing good guys—even though, contrary to popular belief, he has played proper villains before (see The Circle, Cloud Atlas). As Rogers, Hanks does something exceptional in his career: he disappears. Part of what makes Hanks such a beloved actor is his affable screen presence. Basically, he’s always the same guy, and because he remains so pleasant, his appearance onscreen reassures us. It’s a quality Hanks and Rogers have in common, and the actor puts it to incredible use here.

The film arrives in the wake of Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, Morgan Neville’s documentary from last year about Rogers, which reminded audiences of his willingness to confront complex emotions and topical issues in a format suited for the very young—his episodes tackled death, divorce, and war, among other unlikely topics. Rather than sheltering children from the awful truth, Rogers imbued understanding, allowing his audience of children and adults alike to deal with their sometimes negative emotions in a safe, healthy way. And so, perhaps it’s a condition of our world today that, just when humanity seems to be at its worst, filmmakers have sought to find shining examples of humanity at its best. What’s strange about A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is how, rather than centering on Rogers, it tells his story from an interviewer’s perspective. It may seem like an odd choice, except that’s just what Tom Junod did when he profiled Rogers in his 1998 article for Esquire, “Can You Say… Hero?”—the inspiration for Noah Harpster and Micah Fitzerman-Blue’s screenplay.

In the starring role, Matthew Rhys plays Lloyd Vogel, a fictionalized version of Junod. Always seeking a cynical angle, Lloyd has earned a reputation as a magazine journalist who eviscerates his interview subjects. His personal life is no less combative. He’s been distant toward his wife Andrea (Susan Kelechi Watson) and their newborn because he has an uneasy relationship with his estranged father, Jerry (Chris Cooper), and thus father roles. When Jerry shows up at a family wedding after years without communication, the tension brings Lloyd and Jerry to blows. Given Lloyd’s unresolved issues, his editor (Christine Lahti) refuses to send him on a new assignment until he changes his image. She tosses him a 400-word puff piece about Fred Rogers for the magazine’s “heroes” issue, something he should be able to complete in short order. Andrea tells him, “At least it’s someone good.” Lloyd replies, “Yeah, we’ll see.” He only knows of Rogers as a cornball TV personality, and he suspects that, like everyone else, Rogers has some dark secrets.

From the first frame onward, it’s apparent that Heller isn’t interested in a traditional birth-life-death biopic. The opening scene welcomes the viewer into the public television world of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, complete with a boxy aspect ratio, fuzzy picture, and the model neighborhood from the original show. Our resident host, Rogers (Hanks), enters through the front door and sings us “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” as he changes into his comfier show attire, a sweater and tennis shoes. The film proceeds like an extended episode of the show, alternating between Lloyd’s life and transitional scenes with scale model exteriors of New York and Pittsburgh. Cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes and production designer Jade Healy recreate a convincing look and feel to the film, which in turn channels our memory of the show. And on this week’s episode, Mr. Rogers introduces us to Lloyd, who’s having trouble acknowledging his emotions. He’s angry, impatient, and unwilling to forgive his father. “Have you ever been angry?” asks Hanks, who by now has completely dissolved into the Rogers persona. “It’s okay to be angry sometimes.”

From the first frame onward, it’s apparent that Heller isn’t interested in a traditional birth-life-death biopic. The opening scene welcomes the viewer into the public television world of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, complete with a boxy aspect ratio, fuzzy picture, and the model neighborhood from the original show. Our resident host, Rogers (Hanks), enters through the front door and sings us “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” as he changes into his comfier show attire, a sweater and tennis shoes. The film proceeds like an extended episode of the show, alternating between Lloyd’s life and transitional scenes with scale model exteriors of New York and Pittsburgh. Cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes and production designer Jade Healy recreate a convincing look and feel to the film, which in turn channels our memory of the show. And on this week’s episode, Mr. Rogers introduces us to Lloyd, who’s having trouble acknowledging his emotions. He’s angry, impatient, and unwilling to forgive his father. “Have you ever been angry?” asks Hanks, who by now has completely dissolved into the Rogers persona. “It’s okay to be angry sometimes.”

When Lloyd arrives at the WQED studio for a brief interview, he’s taken aback by Rogers’ genuine interest in his life. Rogers has a childlike curiosity and asks Lloyd questions about his wife and father, diverting the conversation away from himself. Lloyd sees this as a deflection at first and wonders what demons it’s meant to conceal. But Rogers tells Lloyd that his goal is to “look through the camera into the eyes of a single child” and give them “a positive way to deal with their feelings.” It’s an outlook that Lloyd rejects as a reflex—he doesn’t know how to manage his anger and harbors only pessimism toward the world (Rogers’ producer, played by Enrico Colantoni, tells Lloyd, “I’ve read your work. You don’t like humanity, do you?”). Meanwhile, Lloyd pores over episodes of the show, as well as Rogers’ guest appearances on Arsenio Hall and Oprah Winfrey, where Hanks has been substituted for the real thing using CGI à la Forrest Gump. But instead of finding some suitable muck to rake, Lloyd comes to recognize that when Rogers speaks, he may do so at a turtle’s pace, but he speaks with sincerity.

The film is structured so that Lloyd experiences an arc because he clashes with Rogers’ profound kindness and willingness to search inward. In a Citizen Kane-esque flourish, Lloyd’s need to conduct research for his profile gives the film a chance to showcase how Rogers was America’s therapist since the late 1960s. But where Lloyd views crowds of people who line up to share their problems with Rogers as a potential burden on the show host, Rogers feels emboldened by their bravery to come forward. This is a man who convinced politicians to support public television for the good of children, who took photos of almost everyone he met because he genuinely wanted to remember them, whose fans sang to him spontaneously on a subway. The invariably steady host becomes an example of someone capable of negotiating his complex emotions and accepting every feeling as a learning experience. When he’s confronted by Lloyd’s frequent rudeness or mistrust, Rogers introduces the journalist to his puppets, which are aspects of his own personality. It shows how Rogers processes emotion, accepting the good as well as the bad, while also never giving up on a friend in need. And Lloyd becomes that friend.

The blending of reality and the TV stage begins to feel intrusive in the latter half of A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, when Lloyd works out his issues in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. The resulting dream sequence, which finds Lloyd transforming into his childhood stuffed animal called “Old Rabbit,” becomes heavy-handed and informed by Psychology 101 symbolism. Similarly, as Lloyd begins to reconcile with his father, Rogers disappears from the film for large sections, replaced by teary deathbed scenes. They’re the sort of scenes that you can feel working you over, and you don’t really mind, apparently, because you can’t help your eyes from welling up with tears. Heller’s most daring move involves Rogers asking Lloyd for a minute of silence to think about the people who “loved us into being,” and during that minute, the frame finds Rogers looking directly into the camera. He says nothing, but it’s as if he’s asking us, “Who loved you into being?” It should compel us into personal reflection; instead, it’s a distracting formal choice, more awkward than a call for self-examination.

But then, most of what happens in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood comes from Junod’s article in Esquire, making it all the more heartening to behold. In his supporting role, Hanks commits to a full embodiment, from Rogers’ vocal inflections to his everpresent smile—it’s much more than an impersonation, much more than a wig and some make-up doing the work. Heller allows Hanks the same quiet humanity that Rogers had, where silences often communicated volumes of empathy and understanding. Heller, who directed the dark comedies The Diary of a Teenage Girl in 2015 and Can You Ever Forgive Me? last year, shows that she’s capable of more than irony and quirk. There’s a careful artistry behind her work here, and her approach saves the material from becoming too saccharine. It goes as dark and as hopeful as Junod was willing to go, while it also commemorates Rogers along the way, leaving the viewer with a very good feeling.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review