Tesla

By Brian Eggert |

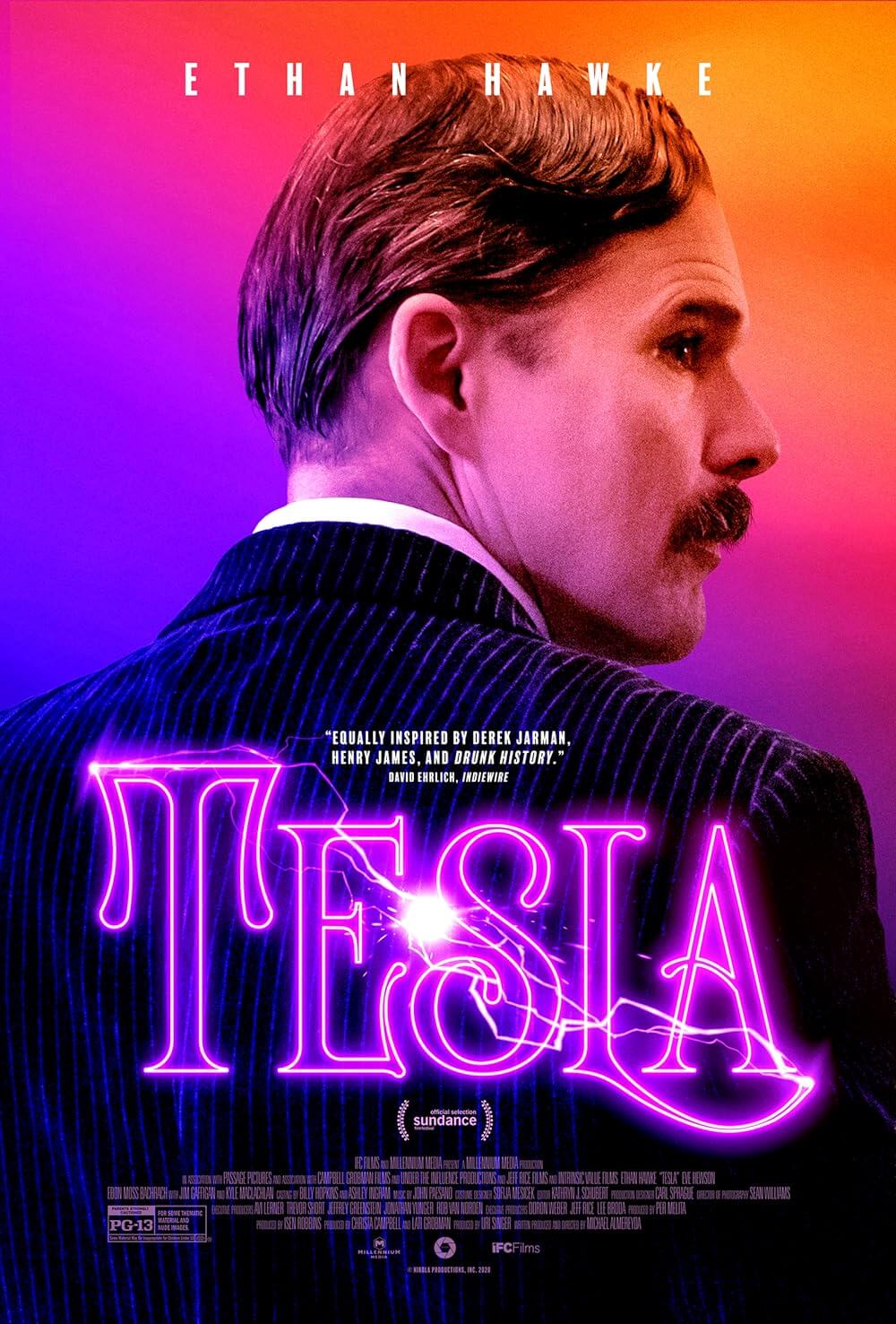

In Michael Almereyda’s Tesla, two nineteenth-century inventors confront each other with ice cream cones. The older, brasher Thomas Edison, played by Kyle MacLachlan, questions the safety of alternating current, licking his dessert as though it were an insult. Ethan Hawke’s Nikola Tesla, the practitioner of alternating current, born in what is today Croatia in 1856, tongues his vanilla treat in defiance. Tesla believes Edison owes him money for his work, and the two men use their cones like swords to stab their opponent. They spar until Tesla smashes his cone onto Edison’s face. The frame freezes. “This is pretty surely not how it happened,” says a woman’s voice. That would be Anne Morgan (Eve Hewson), daughter of J.P. Morgan, who finds herself drawn to the central character. He thinks too much, has no business savvy, and has no interest in self-promotion, but there’s something magnetic about him. Anne frequently breaks into the picture, sometimes addressing the audience directly and sometimes using Google image results to prove a point. She tells Tesla’s story because the inward inventor would never be so self-obsessed as Edison, who, by contrast, would have gladly narrated his own biographical film. That’s part of Tesla’s charm. He’s an eccentric who wants only to explore the ideas in his mind. But it’s also the reason Edison is a household name, and Tesla remains on the margins of history.

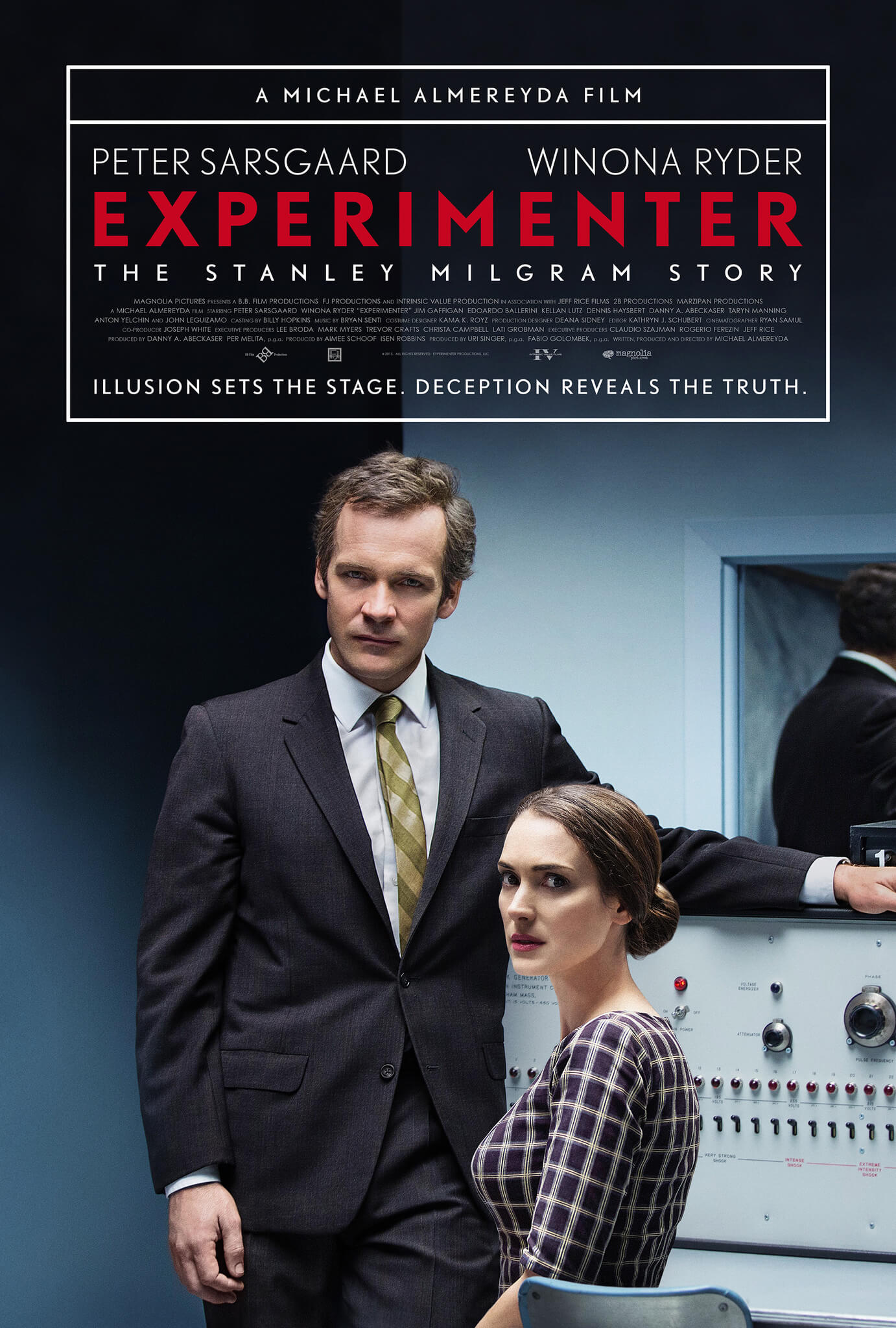

A work of Brechtian filmmaking that feels less like Tesla’s dramatized life story than an essay about how visionaries must contend with the demands of capitalism, Tesla presents a dazzlingly unconventional biopic. Earlier this year, Marjane Satrapi injected some off-the-wall flourishes into Radioactive, her account of Marie Curie, yet she did so within the traditional framework of a biographical drama. As in Experimenter, Almereyda’s 2015 account of Stanley Milgram’s “Obedience to Authority” study, the director commits to a presentation that gets to the root of his subject’s scientific interests without the usual procession of dull, dramatic moments. Instead, there’s something strange and different about every scene, requiring the viewer to constantly assess and reconsider how the film presents its character. It’s less detailed about Tesla’s scientific advancements than Milgram’s investigation into human behavior; there’s no CGI to illustrate the differences between AC versus DC for those viewers who might not remember their lessons from high school science (beyond clarifying that AC results in “no sparks”). But Almereyda’s treatment sympathizes with Tesla’s desire to invent a type of energy that would, hypothetically, eliminate the need to commodify heat, water, and electricity.

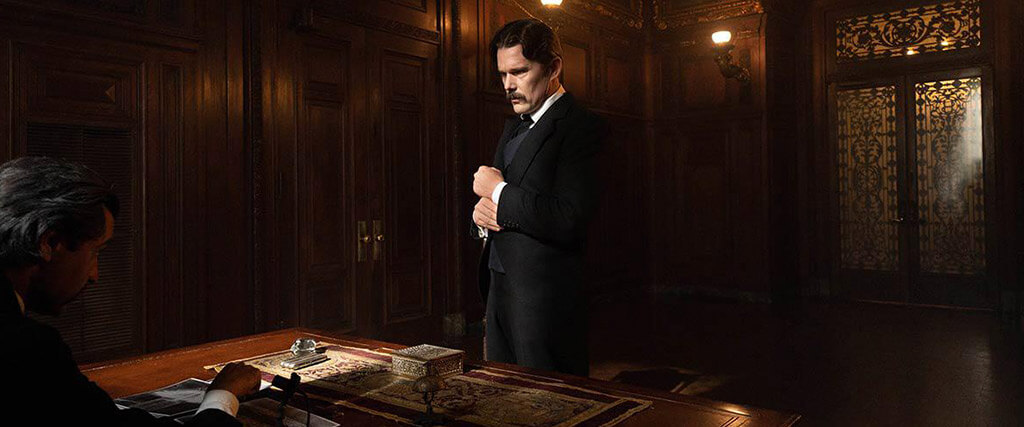

Even though he died alone and destitute in New York, in 1943, having outlived his many competitors and investors, history has been kinder to Tesla. He appears on statues and memorials around the world, and Elon Musk put his name on an electric car. The cinema has used him mostly as a peripheral figure shrouded in secrecy and mysticism. Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige (2006) featured Tesla, played by David Bowie, as a scientist who recognizes that his discoveries looked like magic. Nicholas Hoult played him in last year’s The Current War, albeit in a minor role. Only The Secret of Nikola Tesla, a Polish film from 1980, notable for Orson Welles’ appearance as J.P. Morgan, has given Tesla the full treatment. Still, Almereyda’s film offers insight into why Tesla, ever financially outmatched by the Edisons of his world, was left overshadowed by other captains of industry. When Anne takes out her MacBook and tells us that Google finds just three or four photos of Tesla, yet there are thousands of Edison, she reveals a crucial component of Tesla’s character. Here’s a man whose AC technology illuminated the entire Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, yet he chose, or did not have the promotional acumen, to exploit his talents for personal gain.

Almereyda’s approach could be accused of putting a distance between the viewer and his film, but Anne implants a curiosity about the inventor. She appears just as Tesla’s best advocate, friend and fellow inventor Szigeti (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), heads to South America, leaving Tesla to manage his own affairs with George Westinghouse (Jim Gaffigan) and J.P. Morgan (Donnie Keshawarz). She seems to love him, or at least admire him enough to hope for more. But Tesla’s idealism and obsession with the unattainable— represented by his interest in Sarah Bernhardt, played by Rebecca Dayan—leave him blind to Anne’s willingness to help him achieve his goals with a mutually beneficial coupling. In one of her remarks to the camera, Anne observes that Tesla needed an “enlightened hustler to guide him through the crass commercial world.” Tesla remains oblivious to these concerns, unable to combat Edison’s ruthless smear campaigns, such as a press conference where he kills a dog with alternating current to prove it’s dangerous. While Edison manipulates his image with the public, Tesla dissuades future investors, who think he sounds like a crackpot when he talks about contacting Martians, photographing thoughts, and building an electrical gun.

Similar to Experimenter, Almereyda’s spry and invigorated mise-en-scène, designed by Carl Sprague, keeps the viewer conscious of his simultaneous representation and commentary. Beyond the use of modern devices and Google search result analysis, some of the visual flourishes may have been compelled by the production’s limited budget, reportedly $5 million. Yet, the dialectical approach serves our understanding of Tesla himself. When the inventor looks over Niagara Falls, where he consulted on a massive AC power generator, Hawke appears before a false backdrop on a soundstage, the effect intentional, underscoring how Tesla felt at a remove from the world he inhabited. More than once, the director uses rear-projected images to give his film a stage-like quality. He also uses obvious scale miniatures to recreate the Wardenclyffe plant, where Tesla hoped to use the earth as a conductor to send messages to the other side of the planet. Along with cinematographer Sean Price Williams’ skewed angles and fisheye lenses, or the point of view shots where Tesla sees invisible energy flowing over everything, Almereyda creates a character who lives inside his head, arguably to a fault.

Tesla may cause some viewers to recoil at how Almereyda injects modern devices, uses historically inappropriate references, and breaks the Fourth Wall throughout. But his perspective grants the viewer a better understanding of how Tesla operated both ahead of and outside of time, offering an unlikely example of form-follows-function. At one point, Edison lights up a cigar and defiantly takes out his smartphone, probably to check his Twitter feed. Tesla, meanwhile, probably doesn’t use social media. His more inward approach finds him performing a karaoke rendition of “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” by Tears for Fears on an empty stage. Hawke’s wobbly vocal performance, a sad reflection of a man who rarely expresses himself but had a grand vision—he hoped to use electricity to turn the world “into a huge brain”—offers a performance just as woeful and internalized as his role in First Reformed (2018). Either you will embrace this sort of playfulness, which operates outside of prescribed norms just as Tesla did, or you’ll wish for something more straightforward. In any case, Almereyda has captured the essence of Tesla. From Almereyda’s fascinating emphasis on method over the artifice of a commercial production, we realize that a more traditional film just wouldn’t do.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review