31

By Brian Eggert |

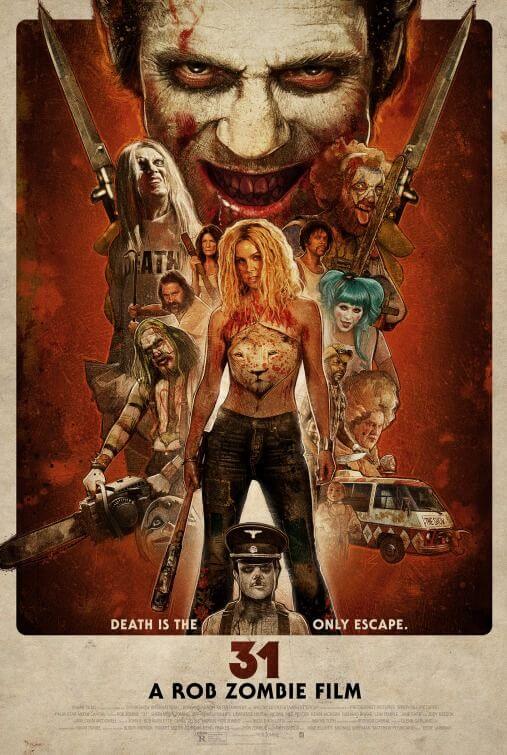

Some abrasive and awful people have a deadly encounter with a group of even more abrasive and awful people in Rob Zombie’s 31, another of the director’s obvious inspired-by-Tobe-Hooper efforts. Audiences familiar with the heavy-metal-singer-turned-filmmaker’s body of work know this description could apply to almost any of his films. What’s the difference this time around? The sheer number of killer clowns, mostly. The writer-director has been exploring clown-faced and masked killers since his debut of House of 1000 Corpses in 2003, featuring Sid Haig’s clowny Captain Spaulding, continuing in The Devil’s Rejects (2005) and his remake Halloween (2007), right on through to The Lords of Salem (2013). In Zombie’s latest sideshow-of-a-movie, a band of unsuspecting carnies must survive an arena of death filled with bizzaro killers in white greasepaint, all as part of a Halloween night survival game presided over by faux-aristocratic bigwigs.

At this point, if you’ve seen one Rob Zombie film, you’ve seen them all. Most of them take place in the 1970s and contain a soundtrack comprised of Southern rock. His trailer park aesthetic employees camerawork that looks grainy and shaky; he lights most sets with neon blues and reds; and the editing cuts away from the action, as though we’re not supposed to see what’s happening or to whom. Sheri Moon Zombie, the director’s wife, usually leads his casts, and he parades her around in skimpy outfits alongside a procession of cult figures familiar to genre fans (Haig, Dee Wallace, Meg Foster, Ken Foree, etc.). As a writer, his dialogue is comprised of clichés abound, while even the most foul-mouthed of us grow tired of hearing his coarse overuse of the F-word and C-word. And he borrows endlessly from Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), hence his obsession with masked psychos.

31 refers to Halloween 1976, the night on which the film’s events take place. Cramped in a sweaty RV, a band of low-grade carnival performers drives to their next gig, shouting caustic-but-friendly insults and lewd remarks at one another. Late at night, they halt the RV at the sight of several scarecrows blocking their passage, only to be jumped by a band of goons. The few of the carnies to survive this initial attack awake to being shackled in an elaborate abandoned factory setting, where three powdered and wigged bluebloods (Malcolm McDowell, Jane Carr, and Judy Geeson) announce, in exaggerated British accents, that the survivors are going to play a game called “31”. Almost immediately, Zombie’s cornball dialogue takes over: “31 is war,” McDowell’s Father Murder explains, “and war is Hell!”

The survivors include Venus (Meg Foster), the carny Madame; the scantily clad Charly (Sheri Moon Zombie); a lively Jamaican, Panda (Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs); the tough Levon (Kevin Jackson); and a cocky performer, Roscoe (Jeff Daniel Phillips). The bigwigs have given these remaining five survival odds, mostly unfavorable toward the women, and soon our would-be heroes learn they have 12 hours to survive “the most violent deaths imaginable” in a deadly course. Once the game starts, gimmicky killers known as “Heads” stalk our carny friends. For example, there’s Sick-Head (Pancho Moler), a Spanish-speaking dwarf who dresses as if Adolf Hitler were a clown.

As the carnies are hunted down and butchered, the audience cannot help think that 31 is anything more than Rob Zombie’s version of The Running Man (1987), with each killer’s shtick more contrived than the last. After Sick-Head comes the chainsaw-wielding clown brothers, Psycho-Head and Schizo-Head (Lew Temple and David Ury); then the German-accented Death-Head (Torsten Voges), accompanied by his randy partner, Sex-Head (Elizabeth Daily). Worst of them all is the final baddie, Doom-Head (Richard Brake), who first appears in the film’s black-and-white prologue, and is introduced later as he copulates to F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922). (Note: Comic fans will notice that Doom-Head looks like a morbid version of the Joker, while Sex-Head looks and acts suspiciously similar to Harley Quinn. Meanwhile, the entire plot seems like a scenario conceived by the X-Men’s villain Arcade, who placed the X-Men in a game called “Murder World”.)

As Doom-Head announces before the final act, “Murder school is now in session!”—a line that will make you laugh either ironically or mockingly at 31. Zombie forces his corny instincts into every line of dialogue, disconnecting the viewer from the experience on any relatable, emotional level. He’s far more interested in the aesthetics of heavy metal horror than telling a good story. To be sure, his film plays like a gruesome music video (such as Zombie’s own “Gore Whore,” the video that debuted just before my advance screening), except featuring songs from Aerosmith and Joe Walsh & The James Gang. It’s all surface, kitschy stuff, and imagery to excite Zombie’s subculture of horror fans.

Indeed, I overheard members of Zombie’s devoted audience call the film “badass” when the end credits started to roll, and so perhaps a select few will celebrate 31 as another of the writer-director’s triumphs. Fans of Zombie’s films—you know who you are—will savor every grisly detail, no matter how nonsensical or stupid the script may be, no matter how little we care about the characters, and no matter how little sense it all makes. Zombie’s films are merely an extension of his own heavy metal music persona and his affection for Tobe Hooper, but they fail to make a connection in any meaningful way beyond the superficially hardcore. And so, the filmmaker remains incapable of and uninterested in appealing to a wider audience outside of his genre. Nevertheless, those who flock to his output will no doubt enjoy the savage, gruesome, ugly, mean-spirited, and empty experience that is 31.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review