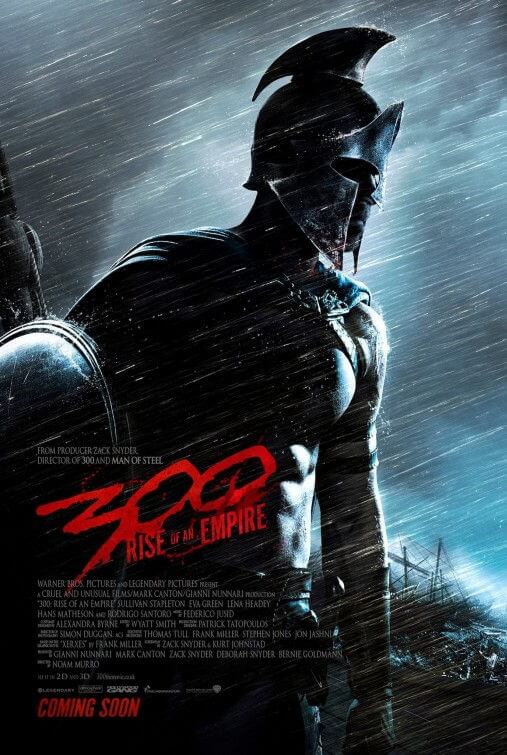

300: Rise of an Empire

By Brian Eggert |

Gratuitous bloodshed and slow-motion blight what might otherwise have been a redeeming sequel to the glaringly overrated 300, Zack Snyder’s machismo-obsessed adaptation of Frank Miller’s graphic novel. The original showcased a clash between two strict ideals, the glory-driven inflexibility of the Spartans as led by their King Leonidas (Gerard Butler), who faced off against the bow-or-die dogmatism of Persian god-king Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro). Leonidas may have fallen, but his martyrdom was remembered, while the muscle-bound Spartans were glorified by style in Snyder’s film. The sequel, called 300: Rise of an Empire, showcases a much more complex and, therefore, more interesting clashing of minds, that between Greek warrior-politician Themistokles and his strategic enemy on the open sea, the ruthless and vengeful Persian naval commander Artemisia. Still, just because the characters are more complex doesn’t mean the presentation is any less rooted in over-the-top displays of hyper-stylized violence for violence’s sake.

Based in part on Miller’s yet-unpublished graphic novel Xerxes, the script by Snyder and co-writer Kurt Johnstad considers events that history shows took place around the same time as the Battle of Thermopylae, as depicted in the original. It also delves into the formation of Xerxes into a god-king after his father’s death at the Battle of Marathon. Left in mourning, the very human Xerxes takes instruction from his father’s most devoted general and the most fascinating character in the film, Artemisia (Eva Green). She sends him into a desert cave occupied by an ambiguous evil, and when he emerges from a golden pool, he’s suddenly 8 feet tall, hairless, a deep baritone, and adorned with golden jewelry. Meanwhile, the story, as recalled by Spartan Queen Gorgo (Lena Headey), also explores Artemisia’s background as a former Greek girl whose hatred for her people was born from a childhood of rape and torture, and focused through her skill in battle.

Upon the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, before the Persians burn Athens to the ground, Xerxes heads to the “hot gates” to contend with Leonidas’ brave 300 soldiers, while Artemisia invades by sea. Anticipating the invasion, naval general Themistokles (Sullivan Stapleton) seeks help from Gorgo in Leonidas’ absence, but his request for reinforcements is declined. As a result, Themistokles and his fleet are dwarfed by Artemisia’s massive Persian navy, and using his guile and expert strategy, he relies on subterfuge to lure the Persians into some well-laid traps. Long frustrated by her lack of a worthy opponent, Artemisia beckons Themistokles to join her, and the two share a violent, sexual power-play in one arresting scene where both refuse to submit, but ultimately Themistokles’ loyalties are to Greece and Artemisia’s to Persia. Their mutual attraction, competition, and yet dutiful conflict are fascinating, perpetuated by Green’s fiery and seductive eyes, and the feeling that at any moment, her character will do something insanely vicious. In one scene, she lops off the head of a failed soldier and kisses his bloodied lips to prove her power.

Unlike the original, there isn’t overt narration throughout 300: Rise of an Empire telling us how austere and devoted to their cause the Spartans are, or in the case, the Greeks. The preachy element has been removed and replaced with inspirational rallying speeches given by Themistokles, many of them derivative of those given in Braveheart and Independence Day. Also removed is the undercurrent of narrow political- and social-mindedness celebrated by Miller’s historically problematic interpretation of the Spartan people, who in his treatment are male-dominated and revile Greek “boy-lovers.” The sequel’s concentration on the Greek navy also forces us to question why the title retains “300” since by the time this sequel begins the 300 Spartans are dead and the story gives way to the much larger Persian invasion. No matter, as Snyder’s original made $456 million worldwide, and Warner Bros. executives need to preserve their name-brand integrity.

In keeping with Snyder’s film, helmer Noam Murro, who’s known for his commercials and the feature Smart People, takes over the director’s chair but preserves the original’s same stylistic approach. CGI-constructed backgrounds and an almost monochromatic visual palette have more variety than 300 due to the variety of sea battles (during the day, through a fog, and in a night battle of fire and explosions). Nevertheless, the production is saddled by Murro’s dogged imitation of Snyder’s style. The amount of slow-motion—not to mention Snyder’s signature speed-up-then-slow-down technique—used in 300: Rise of an Empire is distracting, and one supposes the 102-minute film would run only about an hour if all footage was played at normal speed. The level of bloodshed is also a distraction. While the original certainly had an excessive amount of blood and gore, Murro seems intent on upping the ante with plenty of CGI geysers spraying red at his audience, the effect “enhanced” by the 3D presentation. Blood seems fetishized to an uncomfortable degree, the stuff gushing and, as rendered by computers, looking chunky and fake.

There’s an evident final chapter in a trilogy to follow if 300: Rise of an Empire generates enough attention at the box office, probably involving a united Greece wiping out the Persians in the battles at Mycaleand Plataea. And as the story veers away from Miller’s sexist, homophobic, and war-mongering depiction of Sparta, the characters become more accessible and the material decidedly more watchable. Gerard Butler’s larger-than-life presence is missed here, and the Australian Stapleton doesn’t fill his shoes (although his frenzied performance in Animal Kingdom no doubt earned him the role). But Green more than makes up for in presence what the rest of the cast is missing in bombastitude. In the few scenes where Artemisia unleashes her unremitting vengeance, or the compelling moments between Artemisia and Themistokles, Green enlivens the screen. The rest consists of profuse bloodshed and slow-motion, copying Snyder’s style to mind-numbing extremes.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review