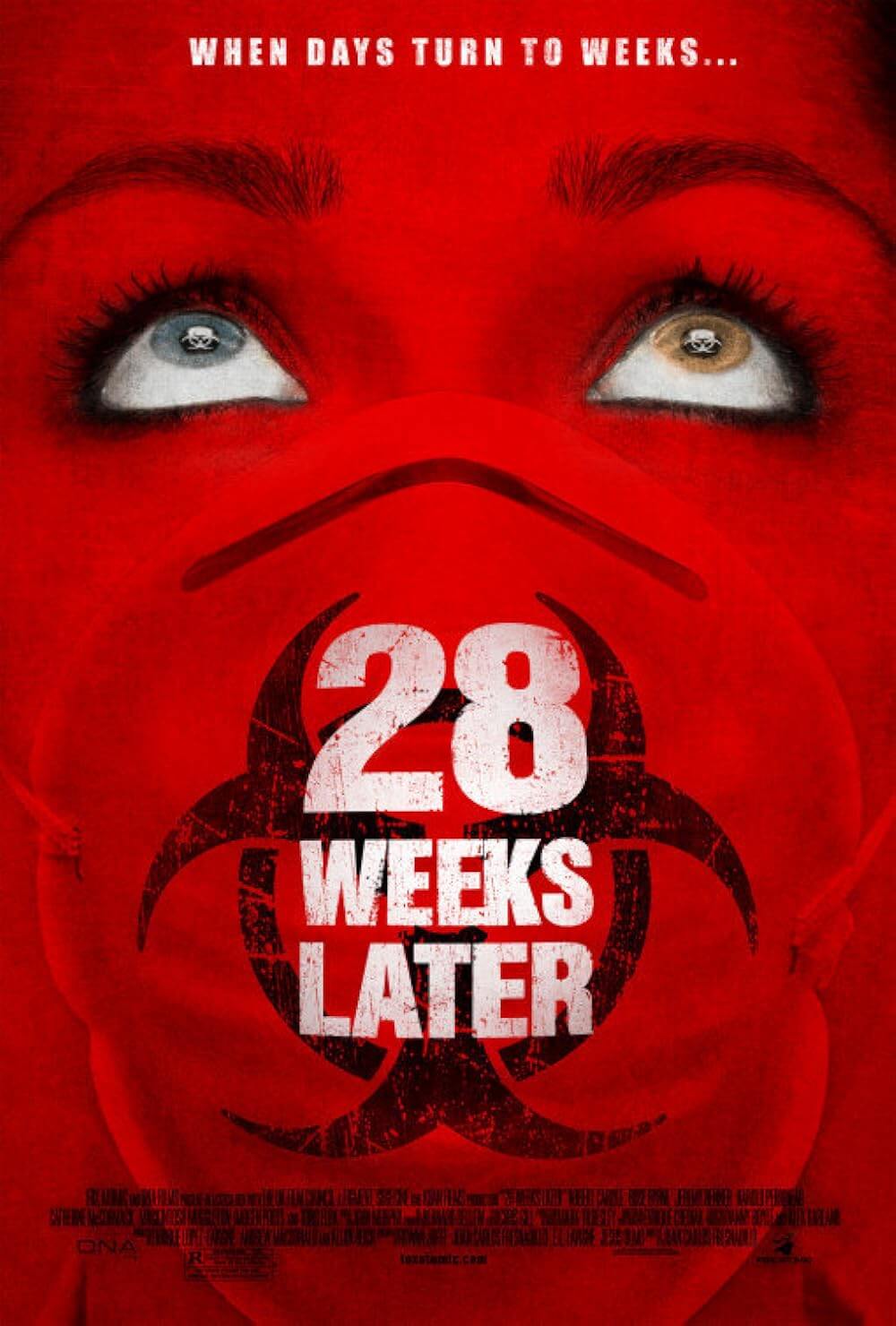

28 Weeks Later

By Brian Eggert |

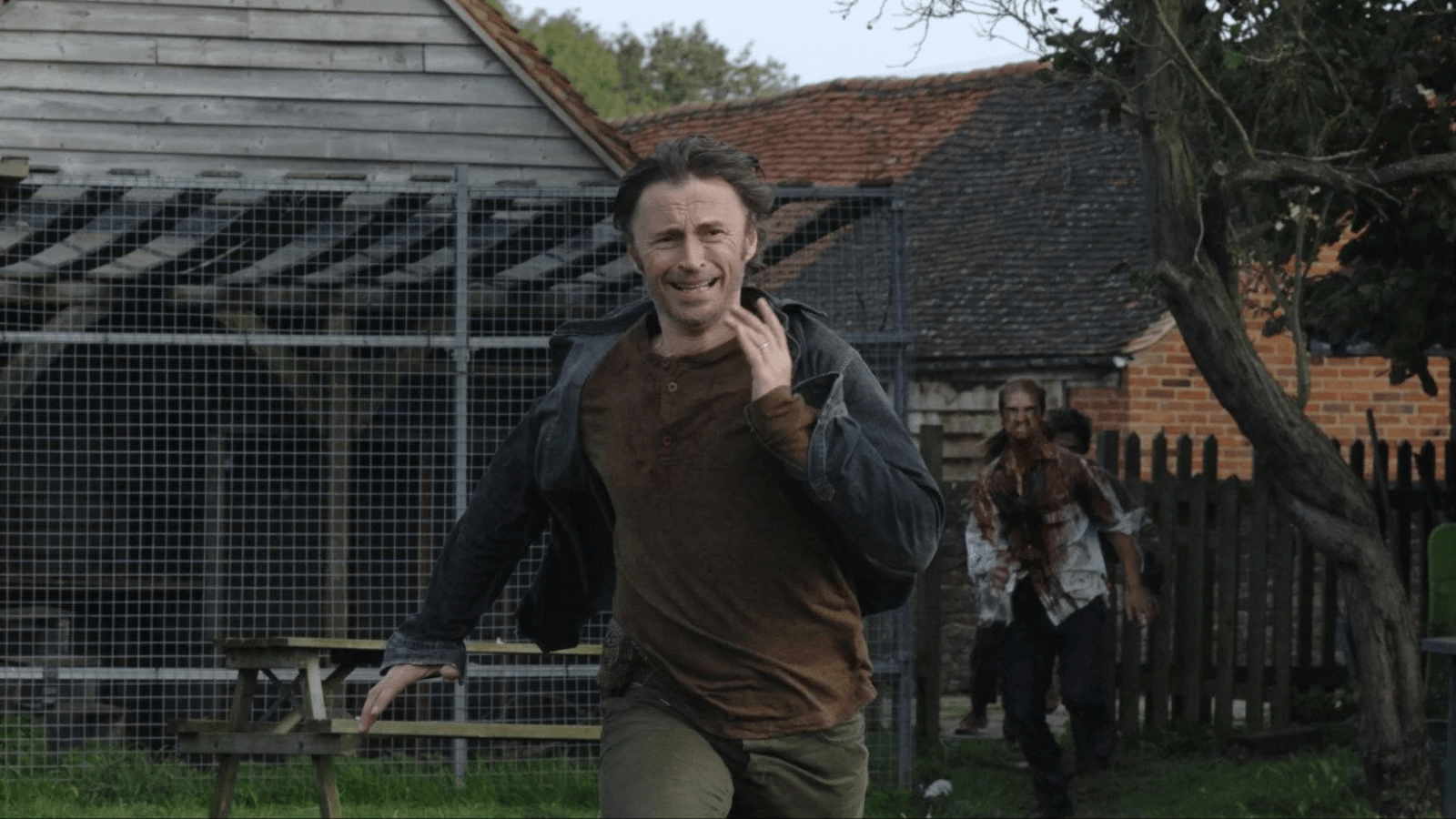

28 Weeks Later opens with a sequence that cannot help but evoke George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). Survivors of a viral epidemic have holed up in a small farmhouse on the British countryside. Married couple Don and Alice (Robert Carlyle, Catherine McCormack), who are grateful their children were abroad during the outbreak, have boarded the windows and now, along with several others, keep quiet to not draw the attention of the accelerated zombies outside. But inevitably, the frenzied Infected, poisoned by rage, smash into the survivors’ temporary haven. Don and Alice try to escape, but several Infected come between the husband and wife. Knowing she is doomed and too cowardly to attempt a rescue, Don abandons Alice. The seething Infected, who are not reanimated corpses but contaminated humans driven by pure hatred in disease form, give chase. Don escapes out of a window onto the lawn; it is a vast field of grass, and he has nowhere to hide. With seemingly endless space in which to move, he is nonetheless confined between the swarming Infected and his slim chance at escape onto a motorboat. Whereas the film’s predecessor, 28 Days Later (2002), is about feeling abandoned in a world devoid of social order or government, 28 Weeks Later is about the opposite feeling of oppressive claustrophobia in open spaces.

Following Danny Boyle’s superb zombie movie innovation, 28 Weeks Later once more turns the zombie film into a visceral, accelerated experience with a cynical message about the institutions established to protect us. Although the gasp-inducing preface resembles Night of the Living Dead in its location, much of the sequel draws from Romero’s later works, specifically Day of the Dead (1985) and Land of the Dead (2005), with their respective themes of an ineffectual military and a reconstructed city doomed to collapse once more. Boyle, unable to direct due to other obligations, turns the reins over to Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, whose earlier thriller Intacto earned him mild praise in 2002. Fresnadillo, working with three other credited screenwriters, turns this co-production between production companies in the UK and Spain into a worthy sequel by reinforcing many of the themes established in the original, while finally expanding the trajectory of the fast-spreading rage virus into a pandemic.

Six months after the zombie-like Infected have starved to death and the area has returned to normal, albeit leaving Britain an abandoned wasteland, U.S. troops oversee the resettlement of the otherwise quarantined country. London’s Isle of Dogs becomes a safe zone, restoring the illusion of infrastructure—complete with running water, electricity, CCTV surveillance, clean living spaces, and even a pub—while armed soldiers and NATO medical staff heavily monitor the incoming and outgoing traffic. Thousands now live in the remnants of the small neighborhood, among them Don, who has survived. Don’s teenage daughter Tammy (Imogen Poots) and his twelve-year-old son Andy (Mackintosh Muggleton, a name seemingly drawn from the Harry Potter-verse) become the first children allowed back into the country. They ask about their mother, and Don changes the events around just enough to remove any question of his guilt. Where Fresnadillo and his writers become perhaps too creative for their own good is suggesting that Alice survived the attack on the farmhouse.

28 Weeks Later introduces the idea that someone, namely Alice, could be a carrier of the virus without succumbing to its rage-fueled symptoms. It’s a notion that expands the mythology of the first film, as every sequel should, while also incorporating a dramatic convenience, the first of many in the film. There’s an uh-oh moment when the children learn that, despite what their father told them, their mother is alive. Meanwhile, Major Levy (Rose Byrne), a medical officer, realizes that the highly contagious Alice carries the rage virus, and at the same instant, Don visits his wife to apologize with a saliva-heavy kiss. Suffice it to say that the quarantine doesn’t hold, and the infection returns. Don, having turned into a blood-spewing, berserk member of the Infected, not only spreads the virus into the otherwise safe population but, in a dramatic flourish that feels overly convenient, he hunts Tammy and Andy amid the ensuing chaos—perhaps propelled by some unconscious disdain for his children that is intensified by his infection. Contrasting the theme of 28 Days Later that places human relationships above unreliable governmental institutions, the sequel acknowledges that the bonds of family and friendship break down, betray, and turn on you in the apocalypse—a profoundly isolating notion to be sure.

When the rage virus penetrates crowds of civilians, we see what was only described with words in 28 Days Later: a crowd swelling with panic, people toppling over one another, and the Infected biting and vomiting their contagion. Fresnadillo and editor Chris Gill render these helter-skelter scenes with an energy that shows how quickly the military’s tightly knit organization and self-assurance unravels. Ordered to shoot down and eliminate any possibility of the virus spreading, soldiers fire into the crowd, killing everyone, infected or not. In 2007, these images could not help but evoke thoughts of the U.S. presence in Iraq, and the so-called War on Terror that resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties. One of the snipers, Sergeant Doyle (Jeremy Renner), gets Andy in his sights and, refusing to fire on a child, he abandons his post to get the children to safety with the help of Major Levy. But their time is short, as Brigadier General Stone (Idris Elba) has ordered the entire area to be firebombed and then saturated with chemical weapons. The complete loss of control over the situation by the military authorities reveals how, in their desperate attempts to contain it, they never had control to begin with. Our sense of security is an illusion, ignoring that no contingency plan can account for the unpredictable or unknown.

Fresnadillo creates a relentless sequel, leaving less room for character development but more opportunity for terrifyingly tense situations. With the city’s power shut down, the concrete jungle setting becomes an oppressive and claustrophobic landscape, and the blackness of London is haunting. The buildings transform into a collection of looming, tangible shadows—something so massively dark that we can’t help but squirm in anticipation for what’s around the corner. The mere thought of the zombie-like Infected instills the perception of limited space. There’s nowhere to run, not when a crowd of them chases after you. As Doyle and Levy lead the children out of the city, they encounter not just the Infected, but soldiers ordered to terminate civilians and clouds of toxic gas cutting off their escape route. Later, Levy directs the children into a pitch-black subway terminal, where they must wander in the dark, guided by the narrow range of vision from a night vision scope. The (mostly) abandoned tunnels press down on the survivors with the confining spaces and oppressive darkness. Similar to Romero’s Land of the Dead, a small safe zone in the city becomes a horrific prison when zombies are unleashed inside—a notion that underscores the theme of how infrastructures betray and ensnare us.

Cillian Murphy’s protagonist from 28 Days Later felt unbearably alone in the abandoned London, but the survivors in 28 Weeks Later feel an empty city squeezing them from every angle. These scenes make us tremble, while the gory violence of the Infected shocks us with its unbridled savagery. It is this combination of styles, the dreadful anticipation that alternates to violent shocks, that demonstrates the filmmaker’s skill at manipulating his audience into feeling crushed by an impossible situation. Fresnadillo carefully interchanges between moments of calm and moments of hopeless chaos—a similar filmic rhythm was equally important to Boyle in 28 Days Later. But the sequel’s mistrust of military institutions is little more than an extension of the ideas established in its predecessor. Even so, Fresnadillo explores those ideas in a format that once more proves terrifying, energetic, and thoughtful in its skepticism. Ultimately, the sequel’s pandemic-facing conclusion has less faith in institutions than the original, making for a bleak, if urgent experience.

(Editor’s note: This review was originally published on May 11, 2007. It has since been expanded and re-edited.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review