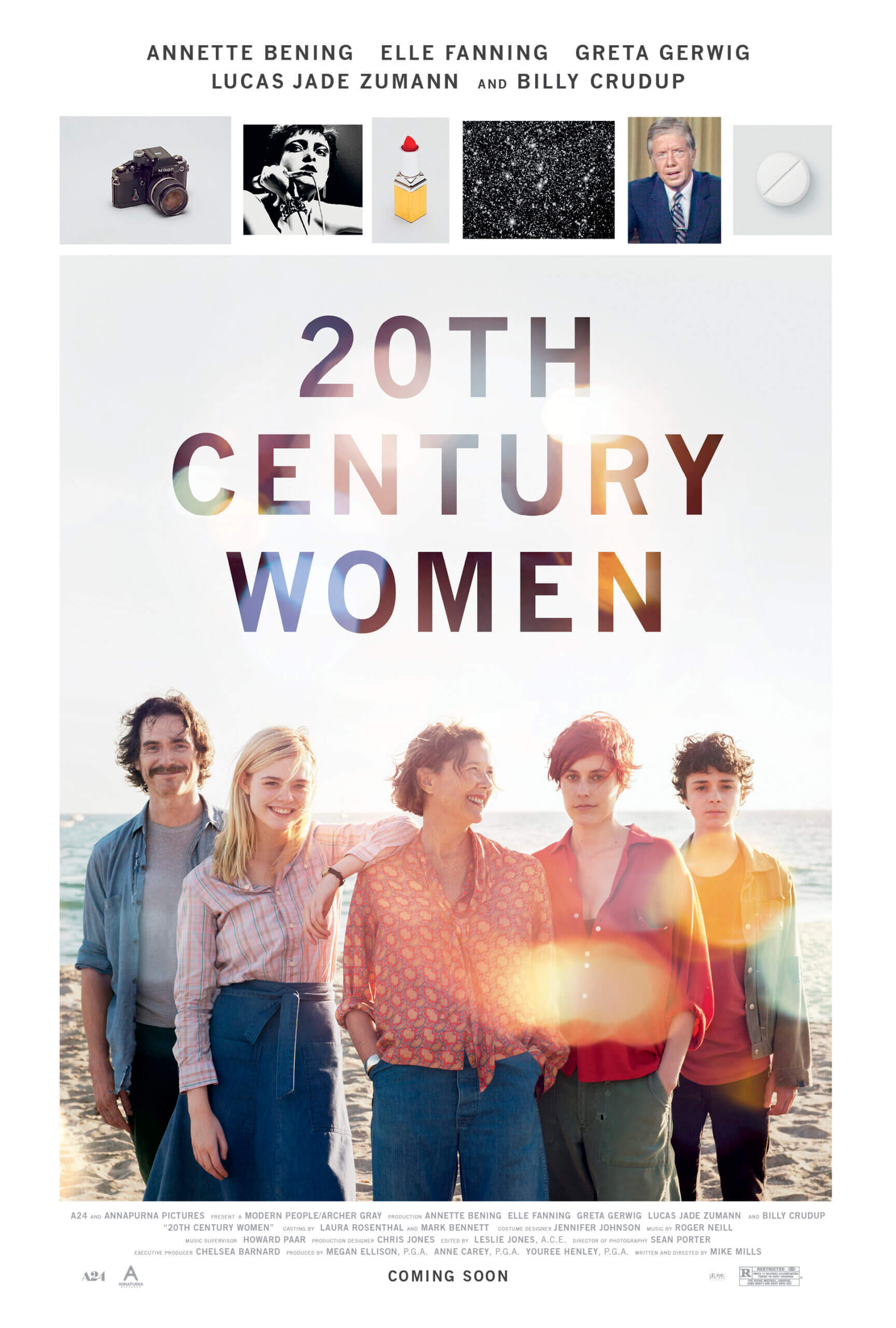

20th Century Women

By Brian Eggert |

Mike Mills’ 20th Century Women takes place in 1979, the year Jimmy Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech echoed throughout the country and ensured his political demise. Imagine it, an American President goes on television to address his morally bankrupt predecessor (Nixon), censure our energy consumption, promote a healthy environment, call out our culture’s greed, and openly acknowledge the country’s widespread existential predicament, all amid the Me Decade. The film’s characters watch the speech with pride and awe, while Mills winkingly opens his film with the Talking Heads’ “Don’t Worry About the Government” against the opening credits; but even listening to that band, which is a favorite of the writer-director (and this critic), might mean someone vandalizes your car with the words “art fag.” By the end of this affecting and dreamily assembled picture, the viewer embraces the result, happily adopting and owning the vandal’s label.

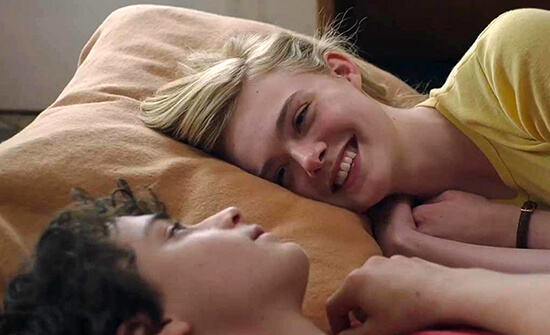

Mills charts the lives of his characters as they search for themselves in Santa Barbara, California, allowing each of them time in the film’s temporally unrestricted use of narration. Consider how the ever-smoking and Birkenstocked Dorothea Fields (Annette Bening) acknowledges how, in two decades, she will die from lung cancer. Knowing the characters’ fates enriches them, giving the audience a sense of the scope of their years beyond the film’s story. Dorothea raises her teenage son Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann) in a communal, neglected stately house that her live-in handyman, William (Billy Crudup), has been renovating. Another boarder, the wine-haired punk Abbie (Greta Gerwig), takes pictures and works through her recent trials with cervical cancer. Less permanent is Jamie’s platonic friend Julie (Elle Fanning), who sneaks into his window at night just to talk and then sleep, though Jamie wants more. Making it worse, Julie openly recounts her uncomfortable sexual experiences with other boys.

Though Jamie remains at the center of the film’s microcosm, he exists as a sponge, absorbing everything the women around him have to offer by way of grace, perspective, and experience. Abbie exposes him to records and demonstrates how to exorcise his frustrations through dance. She also gives him books like Our Bodies, Ourselves and Sisterhood Is Powerful, second-wave feminist texts that enlighten Jamie to the female experience. After reading them, he becomes concerned with how to please a woman through clitoral stimulation, while also becoming acutely aware of his mother’s internalization and quiet desperation. Being a single parent, Dorothea doesn’t quite know what to do with Jamie at this age, and she enlists Abbie and Julie to help shape her son and take an active role in his life. To be sure, 20th Century Women seems to recall a formative time from Mills’ own experiences.

The filmmaker’s last picture, Beginners, a quirky and touching comedy, told the story of Mills’ father, who came out during his septuagenarian years. Mills turned to his mother for 20th Century Women, a portrait both fictional and autobiographical, told in periodic collages and accompanied by the sounds of Devo, the Clash, and the aforementioned foursome headed by David Byrne. At any moment, Mills cuts to an archival black-and-white photo or places titles on the screen so Jamie can read an excerpt from an influential text. A post-modern visualist who plays freely with the formal devices of film speed, voiceover, and editing, Mills creates a lyrical and carefully observed study of people that, though they may serve as composites or approximations, evidently had a major influence on his life. The viewer can sense the profoundly intimate touches throughout the film, as though each scene represents a page or impression in the photo album of Mills’ memory.

Though Jamie may represent Mills, the film does not occupy his perspective alone. 20th Century Women shifts its view throughout to align with William, Abbie, Julie, or Dorothea. We hear their thoughts in voiceover or watch an entire scene from their perspective, such as Julie’s experiences sitting-in on her psychologist mother’s group sessions, or William’s account of what happened in his life after he opened a pottery store in Arizona. But there are also countless endearing moments when everyone comes together, and Mills orchestrates a fluid, lived-in dynamic amid the actors. Take the scene where Abbie insists the guests at a dinner party say and become comfortable with the word “menstruation,” followed by William’s advice on how to make love not to just the vagina but the whole woman, and finally, Julie’s recollection of her rather awful first sexual experience. By this point in the film, our reaction to these equally shocking and hilarious confessions and avowals equate to the understanding we might feel for family or longtime friends.

Scenes both tender and funny create moments in which the actors disappear into their roles. A gentle Crudup and newcomer Zumann hold their own against Mills’ trio of female performers: Bening’s complex, impressive turn is both sad and strong, independent yet compartmentalized. Black-and-white stills recall Dorothea’s upbringing in the Depression to explain away how things were different then; people took care of each other. But Dorothea’s refusal to openly communicate with her son keeps her at a distance. Mills would surely admit he did not entirely figure his mother out before her death. How many of us do? Fanning balances Julie’s elusive and adventurous side with a staggering vulnerability. And Gerwig is perhaps the standout, doing what she does best (in Frances Ha and Mistress America) by playing a woman who must accept that she’s no longer as young as she thinks she is—except, she does so with an incredible degree of rawness and anger here.

Alongside editor Leslie Jones, Mills explores his memories and creates characters through elegiac and ruminative filmmaking, giving the film an art project quality. Though his formal choices never go too far or remove us from the scene at hand, the technical beauty and artistry behind 20th Century Women cannot be denied. Mills follows cars up and down the coast, streaming them with the rainbow colors of an LSD trip. By manipulating the frames-per-second, the uncontainable Julie walks like a J-horror specter, zipping along at a faster pace than everyone else, as if she’s both ahead of the curve and moving too fast for her own good. The film takes an anecdotal form, offering scenes that come together in a stunning and moving patchwork, all of it shot in bright, muted 1970s tones by cinematographer Sean Porter.

Alongside editor Leslie Jones, Mills explores his memories and creates characters through elegiac and ruminative filmmaking, giving the film an art project quality. Though his formal choices never go too far or remove us from the scene at hand, the technical beauty and artistry behind 20th Century Women cannot be denied. Mills follows cars up and down the coast, streaming them with the rainbow colors of an LSD trip. By manipulating the frames-per-second, the uncontainable Julie walks like a J-horror specter, zipping along at a faster pace than everyone else, as if she’s both ahead of the curve and moving too fast for her own good. The film takes an anecdotal form, offering scenes that come together in a stunning and moving patchwork, all of it shot in bright, muted 1970s tones by cinematographer Sean Porter.

Above all, 20th Century Women feels intimate beyond measure, and those who can relate will undergo a deep and meaningful connection to its characters. Mills explores a time and place, the people who lived there, what they were thinking, the music they listened to, and where they ended up in life with sweeping intimacy. Perhaps it’s all to better understand Dorothea, a homebody experiencing Carter’s crisis and trying to figure out where she belongs, but everyone around her feels the same way. Her state of mind reflects the world around her, and it’s a particularly germane perspective. Mills’ formal approach has an emotional logic that may not work for the literal-minded, but then his subjects are not so obtuse; his incredible screenplay and outstanding cast humanize living, breathing people with inexplicable eccentricities and complex interior lives. In no small or insignificant way, Mills explores life in all its uncertainty and individuality, leaving his audience with an undeniable, personal experience.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review