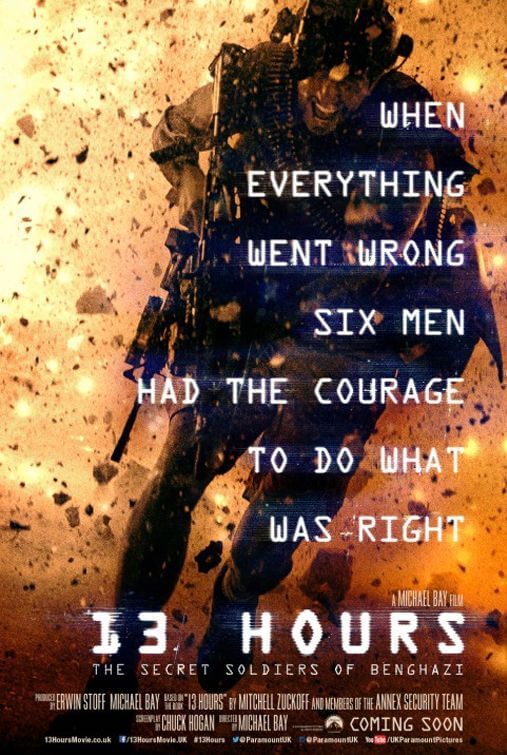

13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi

By Brian Eggert |

When Michael Bay set out to adapt Mitchell Zuckoff’s 2014 book, 13 Hours: The Inside Account of What Really Happened in Benghazi, the director reportedly told the author, “This is going to be my most real movie.” Yes, even more real than Armageddon or Transformers: Age of Extinction. Indeed, Bay’s statement quoted by Zuckoff to The New York Times seems unintentionally funny, since the director’s work is composed of exclusively over-the-top actioners (the closest he’s come to realism is Bad Boys). For his latest, Bay and screenwriter Chuck Hogan changed the title to the equally long 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi, emphasizing the film’s jingoistic, support-our-troops account of the 2012 terrorist attacks in Benghazi, Libya. Less blindly pro-American than American Sniper but more political (by a fraction of a percentile) than Lone Survivor, Bay’s attempt at realism and accuracy is a loud, visually confusing, blur-of-a-film that assaults the senses as only this filmmaker can.

Tensions ran high in Benghazi less than a year after its former dictator Muammar Gaddafi’s downfall. As the real story goes, in 2012, on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, a band of Islamic militants charged an American outpost in Benghazi, an attack that left U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens (Matt Letscher) and U.S. Foreign Service Information Management Officer Sean Smith (Christopher Dingli) both dead. About a mile away, at a supposedly top-secret CIA Annex, another group of Islamic militants attacked, eventually killing two CIA contractors and leaving several others wounded. But Hogan’s script gives the viewer little by way of political or even situational context; why America is in Benghazi and the troubled history of that area is glossed over. This is another example of Hollywood washing over the details in service of an action movie where the American soldiers are the heroes, and the locals are the enemy (“They’re all enemies until they’re not,” says one soldier.). Fortunately, the men who lost their lives and fought to protect American citizens in this warlike situation receive an affecting commemoration.

If only real-life conflicts in the Middle East could be so politically cut-and-dry as Bay makes them seem here. Bay thrusts us into the fracas with a gradual, effective build-up of intensity. But when the shooting starts, there’s only unintelligible action and geographical confusion. Editors Pietro Scalia and Calvin Wimmer deliver jarring cuts that visually our eyes throughout the film. Bay reaches for a visual treatment that conveys the frenzied environment, headed by cinematographer Dion Beebe’s wobbly digital lensing. Meanwhile, during the film’s action scenes, we struggle to differentiate between the American-accented actors with beards and guns playing the titular heroes. They’re all private security contractors and former military men working as part of the Global Response Staff (GRS): Jack Silva (John Krasinski), Tyrone “Rone” Woods (James Badge Dale), Mark “Oz” Geist (Max Martini), Kris “Tanto” Paronto (Pablo Schreiber), John “Tig” Tiegen (Dominic Fumusa), and Dave “Boon” Benton (David Denman).

The GRS isn’t allowed to respond to the militant attack on the American outpost at first; they’re ordered to wait by a CIA chief known only as Bob (David Costabile), who prevents them from rescuing Stevens and Smith in time to save them from the fire that claimed their lives. With only the thinnest layer of backstory applied to each character, a modest subplot about Jack and Rone’s families back home creates sympathy for the characters. Another admirable quality about 13 Hours is that Hogan’s script thumbs its nose at the deadly bureaucracy that delays the GRS from responding in time. Elsewhere, the film notes how the compound wasn’t protected well, its Libyan guards fled in terror, and so-called intelligence on the area wasn’t as good as originally believed. Nevertheless, by simply being a Michael Bay film—and all the mind-numbing action that such a prospect includes—the film avoids taking a political stance unless you count several shots of the American flag taking bullets.

Shaky handheld camerawork and sheer brutality saturate 13 Hours, leaving the viewer to try to assign some political context to the situation. But none exists, and the audience becomes like any machine when subject to too much energy—force enough voltage into the viewer, and they might overload and shut down. Our brains shut down early into 13 Hours and remain in a blackout state for the full two-and-a-half-hour length. Bay’s only concern is creating a “2012 Alamo” shooting gallery; however, the director fails to achieve anything near the cinematic heights found in Ridley Scott’s similarly themed Black Hawk Down. Forget a logical progression of shots that form a scene, like words do a sentence; Bay has no time for such nonsense. He’s more interested in sweeping low-angle shots, jocular humor, and mortar POV shots, all of which will feel familiar to those versed in the director’s filmography.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review