127 Hours

By Brian Eggert |

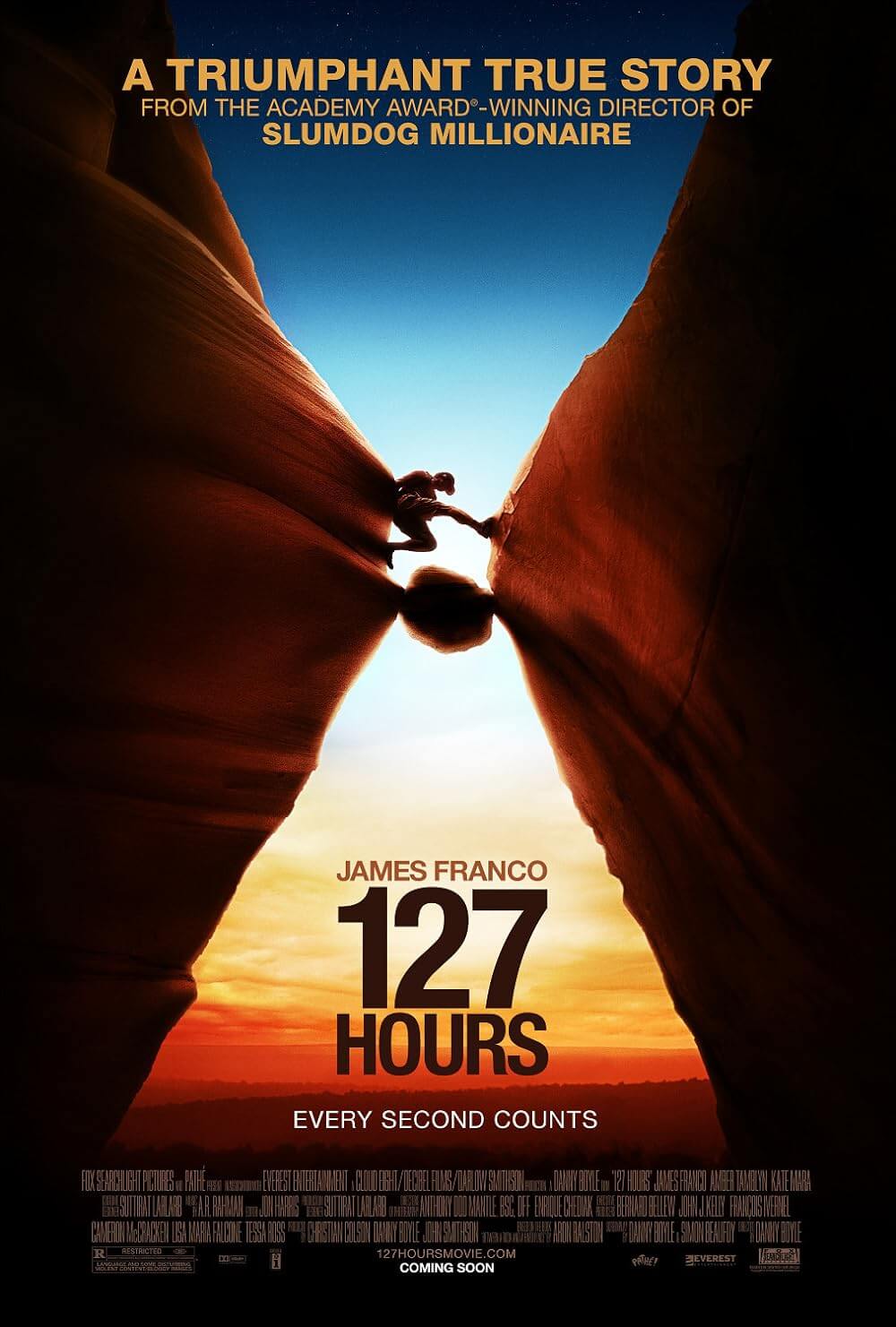

Aron Ralston’s real-life tale of survival isn’t prime material for motion picture filmmaking, if only for the lack of sheer space it covers. With his arm crushed between a boulder and a cavern wall in 2003, the climber spent days confined in an enclosed gap, suffering alone, occupied by only his thoughts and desperate attempts at escape. Committing an entire film to a limited change of scenery for an extended time, leading up to the moment when Ralston cuts off his arm to avoid dying of thirst, presents a directorial challenge—to activate both the space and immobility through innovative camerawork and cinematic cunning. And yet, with Danny Boyle at the helm of 127 Hours, such a restricted cinematic landscape has never felt so vast.

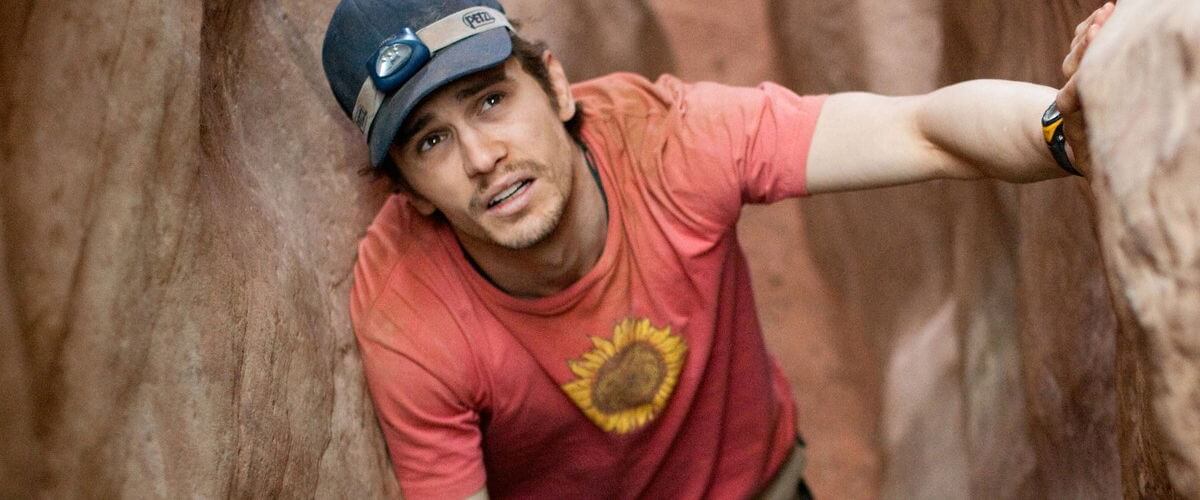

Talk shows and news outlets have already covered Ralston’s story in exhausting detail through interviews and even dramatic reenactments, but none of them have created the level of understanding and sense of ‘being there’ that Boyle does here. This is perhaps because Boyle and the actor portraying Ralston, James Franco, were given exclusive access to the recordings Ralston made during his ordeal. He kept a detailed video diary of his trials using a digital camcorder, and, though never shown to the public, one can only imagine what level of human desperation he captured. Ralston allowed the director and actor behind his story to view the log, and from there Boyle has made yet another exciting, confronting film about living life to the fullest under extremes.

A self-made adventurer and mountain climber, Ralston, age 27, braves into Utah’s Blue John Canyon in April 2003. Set against Indian composer A. R. Rahman’s energetic score, the first fifteen minutes of 127 Hours show Ralston absorbed by every moment. Biking across dangerous terrain, he takes a nasty spill into the sand, takes a picture of his fall, laughs it off, and continues onward. He meets two lost hikers (played by Amber Tamblin and Kate Mara) on the trail and, while they think he’s an enthusiastic weirdo, treats them to a storybook dive in a picturesque crystal blue grotto. When he continues on his own, he overestimates the stability of a foothold and soon finds himself in his life-defining predicament. And this is all before the title appears onscreen.

Boyle and co-writer Simon Beaufoy trigger a fast-moving but ironically stationary narrative, wherein Ralston looks back on his life, dwelling on his mistakes and selfish lifestyle. Beaufoy wrote Boyle’s last film, Slumdog Millionaire, and both won Oscars for their efforts there—no doubt they’ll be nominated for their work here as well. They establish all the necessary situational problems, including lack of food and water, the cold temperatures at night, and the growing physical and mental fatigue. Ralston drifts away into delirious memories, some apparent, others hallucinations designed to manipulate the audience just as they do the protagonist. His mindset fluctuates from lucid to crazed within moments, and it only gets worse as he runs out of water and is stricken with dehydration. Ralston speaks to himself on his video camera and later watches his own outbursts only to plead with himself not to lose his mind. It all leads to an epiphany that forces Ralston into the film’s most upsetting scene, which progresses out of equal parts courage and survival instinct.

Boyle shoots Franco largely in close-ups but moves his camera about with vibrant angles and breakneck editing to keep the film visually engaging. Of course, what cautious moviegoers will wonder is how graphic Boyle makes the eventual self-amputation. To be sure, Boyle doesn’t shy away from the gritty details, as those versed in the director’s Trainspotting and 28 Days Later or even Sunshine will know. When Ralston musters up enough desperation to break the bones in his forearm and begin cutting through his flesh with a dull utility blade, the result will make even the most desensitized viewer squirm, but not merely because of the visible gore. Rather, Boyle shocks the viewer with harsh sounds and sudden cuts to jarring visual flashes. The attention to detail Boyle brings to this scene makes one appreciate Ralston’s incredible resolve, forcing you to ask if put in the same situation, “Could I do that?”

Comparisons to this year’s Buried are unavoidable, as both films revolve around a protagonist whose limited space gives way to a breakthrough performance by the pretty-boy actor portraying him. Here is James Franco, mostly associated with lighter fare such as The Pineapple Express and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man franchise, rendering an excruciating dramatic intensity. Much of his performance involves frustration, pain, hunger, and thirst, but also delusions and dreamy sequences of faraway—one of them involving a frightening appearance by Scooby Doo. And unlike Ryan Reynolds in the sister film, Franco’s performance is about more than panic and sarcasm. The actor demonstrates incredible range that is bound to earn him much-deserved awards consideration.

As most members of the audience will enter 127 Hours aware of how Aron Ralston’s dilemma ends, the experience becomes not one of discovery or will-he-make-it-suspense, but of appreciating Boyle’s cinematic flourishes—his dynamic camerawork, Rahman’s pulsing score, and the organic sense of energy that Boyle brings to every film. In the wrong hands, the story could have easily been toned down to movie-of-the-week quality banality. But the presentation is pure cinema, designed to create the illusion of motion and progress in otherwise stationary circumstances. As always, Boyle displays a directorial intensity that goes unmatched in its momentum and emotional clarity, telling a story that has been told before, but never with such bravado.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review