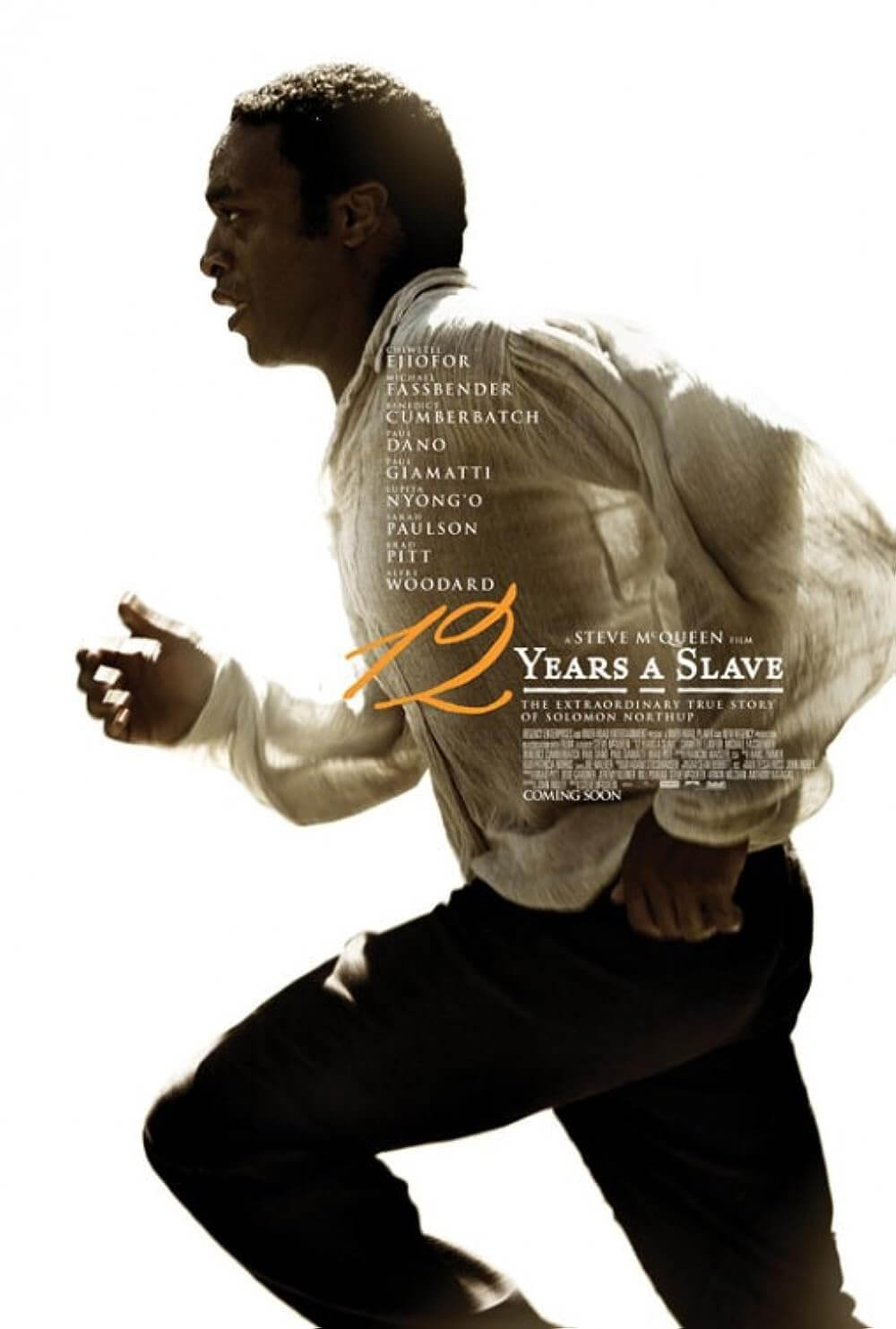

12 Years a Slave

By Brian Eggert |

After the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 but before the American Civil War, the internal American slave trade relied on this peculiar institution to keep pace with the agricultural boom of cotton in the Deep South. Though many slaves were migrated to meet demands, some slave catchers supplied the market by kidnapping free African Americans by way of deceit or force and selling them to traders in the American South. Such an atrocity happened to Solomon Northrup, a free Black man from Saratoga, New York, with a wife and two children. Northrup was kidnapped and sold to slave traders in 1841 and remained in bondage until his unlikely rescue in 1853. Northrup’s full description of his experiences, called Twelve Years a Slave, was published just a year after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And while other anti-slavery texts from the period contain outright political or moral objectives, Northrup’s story represents the experience of slavery with undaunted attention to observed detail.

British director Steve McQueen’s third film, 12 Years a Slave, was based on Northrup’s true story, which details Northrup’s real-life experiences in as many realistic facets as a film can assemble, portraying the willful dehumanization on the part of slave owners to transform human beings into their property and the physical torment suffered by the victims. Unlike other filmmakers who have addressed the subject, McQueen has no reservations about undertaking American slavery in full detail and forcing his audience to witness the shame, injustice, and horror in America’s past. The screenplay by John Ridley condenses Northrup’s account for the screen but nary an aspect is wasted or particular taken for granted. And while the subject matter may seem ripe for an intended awards prestige pic, McQueen’s treatment has all the sobering, rigorous aesthetics of an art film and never panders to the romantic requirements of a commercial audience.

Chiwetel Ejiofor plays Northrup in a devastating performance in which the main character, an educated and worldly violin player, is drugged and abducted by two men promising employment in Washington D.C., the nation’s capital where slavery is still legal. Beset by a world where the protests of a supposed free Black man without papers carry little weight with unruly slavers, Northrup quickly learns the best way to survive is to keep quiet. “I don’t want to survive, I want to live,” Northrup avows, and his hope to rejoin his family keeps him going, even after he’s renamed “Platt” and told never to acknowledge his learned background. For others in Northrup’s situation, such as Eliza (Adepero Oduye), the mother of two whose children are taken from her when a trader (Paul Giamatti) agrees to split her family after she’s sold to plantation owner Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch), hope is less clear. Eliza cannot stop crying, and soon her owners grow tired of her heartbroken wails and resolve to sell her.

A religious man, Ford recognizes that Northrup is an intelligent, talented individual and rewards this with the gift of a fiddle, a present that might suggest Ford’s decency if he wasn’t a slave owner. But Ford’s ignorant and caustic slave overseer Tibeats (Paul Dano) pushes Northrup until he can take no more, and the slave retaliates on his boss, forcing Ford to sell Northrup to the cotton plantation owner Epps (Michael Fassbender) to prevent Tibeat’s otherwise inevitable revenge. Under the vile and cruelly despotic Epps, who believes his slaves are nothing more than cattle, Northrup’s suffering and dehumanization reach a pinnacle. Prone to drink, scripture readings, and sexual advances toward his female “property”, Epps is evil incarnate, partnered in a distressed marriage by his equally cruel wife (Sarah Paulson), who takes out her frustrations on the object of her husband’s affections: a young beauty named Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o). Patsey would rather die than endure as Northrup has done, and in a heartbreaking scene, she begs him to end her life, a request he later surely regrets refusing.

A religious man, Ford recognizes that Northrup is an intelligent, talented individual and rewards this with the gift of a fiddle, a present that might suggest Ford’s decency if he wasn’t a slave owner. But Ford’s ignorant and caustic slave overseer Tibeats (Paul Dano) pushes Northrup until he can take no more, and the slave retaliates on his boss, forcing Ford to sell Northrup to the cotton plantation owner Epps (Michael Fassbender) to prevent Tibeat’s otherwise inevitable revenge. Under the vile and cruelly despotic Epps, who believes his slaves are nothing more than cattle, Northrup’s suffering and dehumanization reach a pinnacle. Prone to drink, scripture readings, and sexual advances toward his female “property”, Epps is evil incarnate, partnered in a distressed marriage by his equally cruel wife (Sarah Paulson), who takes out her frustrations on the object of her husband’s affections: a young beauty named Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o). Patsey would rather die than endure as Northrup has done, and in a heartbreaking scene, she begs him to end her life, a request he later surely regrets refusing.

McQueen applies the same method he used in his previous two features, Hunger and Shame, by employing long, unbroken takes so his audience might grasp the full severity of the conditions and their implications. McQueen does not interrupt our view and does not remind us through editing that “It’s only a movie.” In his 2008 debut Hunger, McQueen’s muse Fassbender stars as Provisional Irish Republican Army martyr Bobby Sands, and the director refuses to look away as Sands is gradually reduced to skin and bones in his fatal hunger strike of 1981. For 2011’s Shame, McQueen again used Fassbender to explore the desperation of sex addiction, and his unflinching lens earned the picture an NC-17 rating. For 12 Years a Slave, there’s a scene where Epps forces Northrup to lash Patsey on the post, the unbroken shot gruelingly long and unrelenting as Northrup tries to lighten his strokes, that is until Epps takes over and unleashes his fury on Patsey’s back.

Depicting the full measure of the torment endured by slaves may earn 12 Years a Slave some criticisms for its representation of violence on film, but no amount of harsh moviemaking could equal the reality. Out of a sense of historical accuracy, McQueen doesn’t recoil from the cruelty, but he brings a sad poignancy to even the most unbearable scenes. Consider the painfully long sequence of Northrup’s near-hanging after he beats Tibeats, his neck noosed and his feet touching the muddy ground below just enough to prevent his suffocation. Around Northrup on the plantation, other slaves go about their business because they’ve been conditioned by fear or because they’re simply accustomed to such sights, all while Northrup gasps for air. Such scenes in the picture are not engineered to depict the brutality itself; rather, they illustrate the more damaging effects of fear on the human spirit. Indeed, even those white men who show some basic human decency toward Northrup, such as Brad Pitt’s Canadian carpenter, writhe in fear over reprisals from the Southern man’s hatred and ownership of slaves. But McQueen’s unwavering treatment also finds beauty in the Louisiana shooting locations. Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt captures almost Terrence Malick-esque shots peering through the trees at the sky as if to look up for its god-fearing characters and ask, What kind of God would allow this crime against Nature?

To counteract the rampant inhumanity onscreen, Ejiofor’s enlivened eyes convey so much life, dignity, and fortitude. When Northrup is finally returned home, he’s so overwhelmed that he can offer few words to his family beyond a needless apology and the tragic understatement, “I’ve had a difficult time these last several years.” Excellent in Dirty Pretty Things, Serenity, and Redbelt, Ejiofor has never delivered this kind of performance, which is enhanced by McQueen’s lingering shots on the actor’s physical and spiritual punishment, the film entrenched in Northrup’s experiences. But if Ejiofor’s presence offers the quintessence of human endurance, Fassbender channels pure hatred onto the screen in a display of acting that is not so much a performance as an elemental force. Epps is rapt by an unhinged tension and hunger for power, given to outbursts of violence and subtle paranoia. Fassbender commits to this physical role completely, the detestation flowing beneath the surface. Nyong’o, Cumberbatch, Dano, Pitt, and the entire cast all serve the film well, never once taking us out of the picture despite their “names”. And Hans Zimmer’s elegiac score plays low throughout, save for his horns from Inception that cry out and reverberate during Northrup’s anguish. Zimmer’s music is further joined by affecting and buoyant songs bellowed by the slaves.

To counteract the rampant inhumanity onscreen, Ejiofor’s enlivened eyes convey so much life, dignity, and fortitude. When Northrup is finally returned home, he’s so overwhelmed that he can offer few words to his family beyond a needless apology and the tragic understatement, “I’ve had a difficult time these last several years.” Excellent in Dirty Pretty Things, Serenity, and Redbelt, Ejiofor has never delivered this kind of performance, which is enhanced by McQueen’s lingering shots on the actor’s physical and spiritual punishment, the film entrenched in Northrup’s experiences. But if Ejiofor’s presence offers the quintessence of human endurance, Fassbender channels pure hatred onto the screen in a display of acting that is not so much a performance as an elemental force. Epps is rapt by an unhinged tension and hunger for power, given to outbursts of violence and subtle paranoia. Fassbender commits to this physical role completely, the detestation flowing beneath the surface. Nyong’o, Cumberbatch, Dano, Pitt, and the entire cast all serve the film well, never once taking us out of the picture despite their “names”. And Hans Zimmer’s elegiac score plays low throughout, save for his horns from Inception that cry out and reverberate during Northrup’s anguish. Zimmer’s music is further joined by affecting and buoyant songs bellowed by the slaves.

Proper films about American slavery are few, the subject and lasting bigotry in America too close to home for many audiences. Films such as Steven Spielberg’s Amistad or the much-lauded TV miniseries Roots acknowledge the events and their immorality but never explore the horrors of slavery with entirely factual objectivity. Even Quentin Tarantino was condemned in some circles for Django Unchained, which examined the savagery of slavery through the guise of a difficult, yet pop-culture-laden cinematic experience. And yet, Tarantino’s vibrant and cathartic revenge story was an escapist delight when compared to the persistent terror in McQueen’s film. 12 Years a Slave is unsettling and painful to behold, but from the lows of human civilization emerges a courageous and moving motion picture. After viewing and enduring McQueen’s film, one wonders if an American director ever would have dared to tell Solomon Northrup’s story in such a manner, at least without being censured for representing too much truth about the evils in America’s history—which America is desperate to forget and when remembered, rarely does so in full detail. If McQueen’s effort does as it should and opens the doors for further advanced explorations of American slavery, then 12 Years a Slave‘s impact will be even more important than the film itself.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review