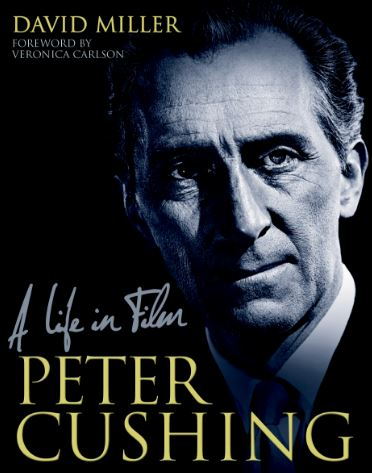

Peter Cushing: A Life in Film

By Brian Eggert | April 10, 2013

Most cineastes born in the last three or four decades probably first saw Peter Cushing onscreen in George Lucas’ original Star Wars, playing Death Star commander Grand Moff Tarkin, a role that came at a downturn in the British actor’s career. As with many creative choices in that film, Lucas cast Cushing because he was a longtime fan and wanted to pay homage. Cushing said the character’s name sounds like something that leaps out of the cupboard, but he’s incredibly pensive and nervous in the role, his physical presence and internal workings evident in his expressions. My own childhood memories of Cushing recall his intense and frighteningly morbid version of Dr. Frankenstein in Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and its many sequels. What an intimidating actor, perhaps even more so than his counterpart Christopher Lee, who played Frankenstein’s monster and the Dracula to Cushing’s Van Helsing in Hammer’s horror franchises.

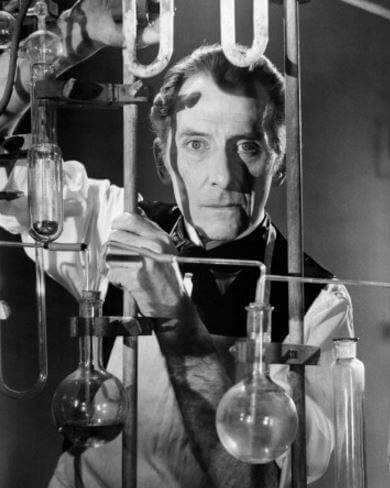

Most cineastes born in the last three or four decades probably first saw Peter Cushing onscreen in George Lucas’ original Star Wars, playing Death Star commander Grand Moff Tarkin, a role that came at a downturn in the British actor’s career. As with many creative choices in that film, Lucas cast Cushing because he was a longtime fan and wanted to pay homage. Cushing said the character’s name sounds like something that leaps out of the cupboard, but he’s incredibly pensive and nervous in the role, his physical presence and internal workings evident in his expressions. My own childhood memories of Cushing recall his intense and frighteningly morbid version of Dr. Frankenstein in Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and its many sequels. What an intimidating actor, perhaps even more so than his counterpart Christopher Lee, who played Frankenstein’s monster and the Dracula to Cushing’s Van Helsing in Hammer’s horror franchises.

What we learn from the new book Peter Cushing: A Life in Film is that Cushing became unfortunately typecast by the mid-1950s, and that his personal life and early career are nothing like what one might expect from an actor commonly associated with British horror movies. Author David Miller delivers a detailed biography which explores Cushing’s years in Hollywood, his time on stage and on BBC television, his eventual step into cult horror and science-fiction, and finally his slow decline after the passing of his wife Helen, the love of his life. This touching and sometimes saddening story paints a portrait of an actor whose presence as a performer was overshadowed by the popularity of his genre B-movies, making readers ache at the thought that we’ve forever missed Cushing’s celebrated stage renditions of Hamlet or Crocker-Harris from The Browning Version.

Miller’s approach takes us chronologically through Cushing’s young life in England as an aspiring actor who finally breaks into his chosen field after ridding himself of an embarrassing accent. Between odd jobs and the occasional stage performance, he saved for a trip to Hollywood in 1939, where his first job as a stand-in on Frankenstein director James Whale’s The Man in the Iron Mask expanded into the role of “second officer”. His career began to take off in small dramatic parts and a slapstick role in Laurel and Hardy’s A Chump at Oxford (1940), but he soon went back to his home in England after the declaration of war with the Nazis. Moving across the states to New York City, he performed for NBC radio programs and did some theater work and saved money for a ticket home. When he finally made it back, his career focused largely on theater for the next decade; noted productions of War and Peace, The Rivals, and Hamlet gave way to his rise on BBC television in the 1950s, including a masterful version of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954).

During this period, Hammer Film Productions sought Cushing out, and he made his first appearance of many as a mad doctor, playing Victor Frankenstein in the aforementioned The Curse of Frankenstein. He continued his relationship with Hammer for several years, making The Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas (1957), Dracula (1958), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Mummy (1959), and dozens more for the studio, which introduced blood and gore into horror movies in a way no film had done before. These films would be his legacy, but his talent reaches even further. As Miller points out, Cushing is the kind of actor who could play a madman in one film and a dryly effective version of Sherlock Holmes in Hammer’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) the next. Alongside genre actors like Vincent Price and Robert Quarry, Cushing played heroes like Van Helsing and Dr. Who with a solemn dignity, and played weirdoes and occultists with an undercurrent of humanity in their morbid behavior.

And yet, Miller makes Cushing’s cinematic legacy seem secondary to the actor’s companionship with his wife Helen, whom he married in 1943. Cushing’s career revolved around those roles which accommodated his personal life, including bouts of depression and, later, a hysterical suicide attempt when Helen died in 1971. His career after Helen’s death consisted of filling roles which were “just killing time” until he was reunited with Helen in the afterlife. Reading about how her loss affected him is simply heartbreaking, adding a new dimension to his roles after her death. Nevertheless, he’s described in Miller’s text as a consummate professional by the author’s many interviews with Cushing’s fellow actors and friends. Perhaps Cushing’s experience in the theater taught him to take each role seriously, no matter how many Tesla coils fill the backdrop or fake blood sprays in the foreground. Cushing noted that he would have preferred playing Shakespeare and the Classics on stage, but no one wanted to see him play Hamlet—they wanted to see him hunt vampires and murder unsuspecting young women.

And yet, Miller makes Cushing’s cinematic legacy seem secondary to the actor’s companionship with his wife Helen, whom he married in 1943. Cushing’s career revolved around those roles which accommodated his personal life, including bouts of depression and, later, a hysterical suicide attempt when Helen died in 1971. His career after Helen’s death consisted of filling roles which were “just killing time” until he was reunited with Helen in the afterlife. Reading about how her loss affected him is simply heartbreaking, adding a new dimension to his roles after her death. Nevertheless, he’s described in Miller’s text as a consummate professional by the author’s many interviews with Cushing’s fellow actors and friends. Perhaps Cushing’s experience in the theater taught him to take each role seriously, no matter how many Tesla coils fill the backdrop or fake blood sprays in the foreground. Cushing noted that he would have preferred playing Shakespeare and the Classics on stage, but no one wanted to see him play Hamlet—they wanted to see him hunt vampires and murder unsuspecting young women.

After retiring in 1987 following a string of sad performances in low-rent productions and his death in 1994, Cushing became a genre icon, and this book celebrates his career lovingly. Behind Cushing’s skeletal frame and deathly pale blue eyes was an extraordinarily subtle and effective performer who disappeared into his roles and often brought an unlikely level of humanity to monsters. Miller’s book helps inform his sometimes unfairly overlooked performances with biographical insight to deepen what we see of Cushing onscreen. And though I’ve read biographies on other film icons whose personal exploits sometimes outshine their career (Errol Flynn) or whose offscreen life seems defined by their film celebrity (Alfred Hitchcock), Peter Cushing: A Life in Film represents a unique read, in that Cushing’s personal and professional lives progressed separately yet parallel.

By the end, though Miller shows his affection for the actor’s career throughout, there’s a bittersweet quality to the book because he’s done such an excellent job defining the actor’s personal life as Cushing’s primary drive, as opposed to him being an actor first and husband to Helen second. The book, which marks the centenary of Cushing’s birth, is a distinctly human approach to a movie star’s biography and, being rather short (about 175 pages) and populated with crisp and bright photos (both promotional and personal), it becomes an easy recommendation for die-hard enthusiasts and even casual fans of Peter Cushing.

Many thanks to Titan Books for sending a review copy of Peter Cushing: A Life in Film. You can order it from Titan’s website.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review