MSPIFF 2025 – Dispatch 2

By Brian Eggert | April 7, 2025

The films below were screened at the 44th Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival (MSPIFF44), which runs from April 2-13. Check here for the full lineup and check back for additional dispatches. Select films reviewed below will receive separate full-length writeups, some for their wider release, some exclusive to Deep Focus Review’s Patreon. In the meantime, here are some first impressions.

Quisling: The Final Days

A timely historical drama that examines the complex, demented psychology of authoritarians, Quisling: The Final Days is a thoughtful Norwegian production about Vidkun Quisling, the Nazi collaborator who ran the puppet government throughout the occupation of Norway during World War II. Director Erik Poppe has explored similar subject matter before in The King’s Choice (2016), about the days surrounding the Nazi invasion of 1940. However, the helmer’s approach here proves far more spiritual and existential, probing the mindset of a man warped by his devotion to an ideology. It’s a rare film that reminds us that, while it’s easy to portray Nazis as evil monsters, beneath each one is a human being, albeit twisted to hateful and destructive ends.

Screenwriters Siv Rajendram Eliassen and Anna Bache-Wiig based the material on the diaries of pastor Peder Olsen, played here by Anders Danielsen Lie. Assigned by the Oslo bishop (Lasse Kolsrud) to help Quisling (Gard B. Eidsvold) recognize his crimes and repent, Olsen, a hospital chaplain, takes a job others have refused. He even resolves to keep the task secret from his wife, Heidi (Lisa Loven Kongsli), who describes living under fascist rule as a persistent knot in her stomach, untied in 1945 when the Norwegian resistance and police began rounding up collaborators. She would not and does not understand how Olsen could give this man sympathy. By contrast, Quisling’s much younger Ukrainian wife, Maria (Lisa Carlehed), is unwaveringly devoted to her husband, chillingly so.

Quisling goes on trial for his crimes, for which there is no defense, and he’s inevitably set to be executed. Meanwhile, Olsen’s task to help Hitler’s subordinate realize the extent of his crimes seems impossible. How do you convince someone so submerged in Nazi ideology—what psychologists describe as “mentally impaired”—that they are wrong? Much of the film unfolds in Quisling’s prison cell, the courtroom, and Olsen’s home. With a composed handheld camera, cinematographer Jonas Alarik captures Pia Wallin’s superb production design in yellow-green hues, as though the occupation has rendered Norway temporarily putrid. Amid the classical period piece presentation, editor Einar Egeland deploys jump cuts and erratic edits, often to convey either Quisling or Olsen’s fractured mental state.

Most effective is how Poppe shows Quisling on the cusp of recognizing that he harmed the Norwegian people, despite maintaining his innocence, even after being shown evidence of mass graves. Everyone’s the hero of their own story, I suppose. Olsen’s task is to reframe Quisling’s perspective, facing off against the maddening mental gymnastics that Quisling uses to justify his actions. This is echoed in Olsen, who helped hide an older Jewish couple during the occupation until it became too great a risk. Unaware of what was happening at Nazi concentration camps, Olsen’s gradual sense of culpability over their probable deaths never finds its equal in Quisling, but it helps him put Quisling in perspective.

Eidsvold is a force of nature as Quisling—a character who identifies with Jesus and believes he had Norway’s best interests in mind by siding with Nazis to stop Bolshevism. History would turn his name into an eponym for collaboration. But Lie (The Worst Person in the World, 2021) carries the film’s heart, refusing to see Quisling as anything less than a human being. The film’s spirituality yearns for something deeper than, say, the similarly themed Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973). Unlike the crimes purveyed by the Nazis and their collaborators, Poppe’s film refuses to dehumanize its villain, resolving to assess how ideology can corrode a mind prone to fanatical zeal, ignorance (both willful and not), and a fragility that recalls today’s authoritarian leaders. 3.5/4 Stars.

LUZ

Much has been written about humanity’s dependence on the internet, social media, and online communities to build relationships, particularly related to horrifying experiences, deception, and predation. But with LUZ, Hong Kong writer-director Flora Lau takes an optimistic perspective on how technology, specifically online virtual reality games, can bring people together. Most movies about VR present cautionary tales about the dangers of losing oneself in artificial environments—see Total Recall (1990), The Lawnmower Man (1992), Virtuosity (1995), and eXistenZ (1999). However, Lau charts two relationships brought closer together in a digital realm. Although its conception of what VR gaming looks like feels awkwardly retrofuturist at times, the genuine emotions conveyed by the terrific cast make up for what Lau’s visualization of the titular game lacks.

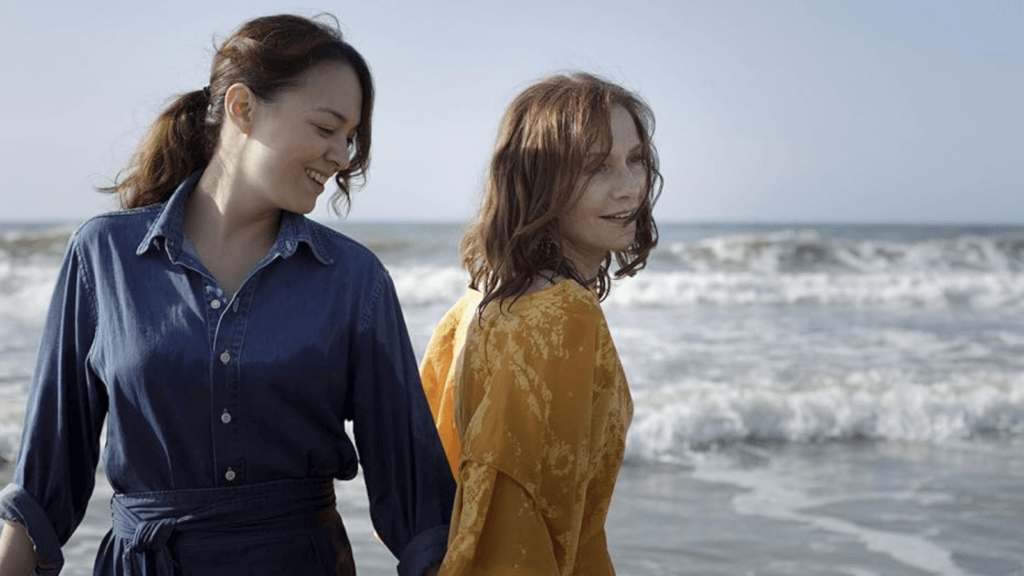

Xiao Dong Guo plays Wei, an enforcer for a powerful gangster who hopes to reconnect with his estranged daughter, Fa (Enxi Deng), who works as a cam girl. Wei subscribes to her livestream anonymously and, fortunately, her show never veers into sexual exploitation while Wei watches. Knowing she plays LUZ, he resolves to order the requisite goggles and hand sensors to find her in the virtual world. In a loosely connected second storyline, Wei’s boss owns a painting by a late, renowned artist whose daughter Ren (Sandrine Pinna) returns to France to reconnect with her ex-stepmother, Sabine (Isabelle Huppert). Sabine suffers from complications stemming from an aneurysm. Ren meets Wei in the game and helps him locate Fa, while the game also brings her closer to Sabine, albeit not to the same extent as Wei and Fa.

Marked by first-person POV shots, prism-like light refractions, and pixelated transitions, the gameplay never resembles a next-gen game. The objective of LUZ, too, feels simplistic—players must attempt to catch a mystical deer in one of its many worlds. “It’s much better than the real world,” claims Ren. “I don’t even know what that means,” responds Sabine. Indeed, if the game looks so outdated that it doesn’t feel advanced, the drama built around these devoted and reluctant gamers fares better. Pinna is excellent as a woman attempting to find her place in the world, only to realize that human relationships can be supported by technology. Huppert, as ever, finds prickly humor and humanity in her role. If Lau’s film naively ignores the downfalls of losing oneself in virtual worlds, it shows that, in some cases, such devices may work as intended. 3/4 Stars.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review