“Joyland” by Stephen King

By Brian Eggert | June 9, 2013

Forget any marketing or official blurbs you might have read about Stephen King’s latest book, Joyland. In fact, forget any preconceived notions you might have about King himself. The official synopsis for Joyland suggests it’s a spooky tale about ghosts and an amusement park killer—a scenario perfectly suited for this author of the macabre, whose work has been adapted to film almost as much as Shakespeare. But within the first few dozen pages, the reader begins to discover the reality is much different than the marketing. This isn’t one of King’s 1,000 page tomes—such as The Stand and It, or more recently Under the Dome—filled with countless intersecting characters, endless flashbacks, and potboiler suspense. Nor does it meet the requirements of crime fiction, as intimated by the publishers at Hard Case Crime. Quite the opposite. This is perhaps King’s most touching book.

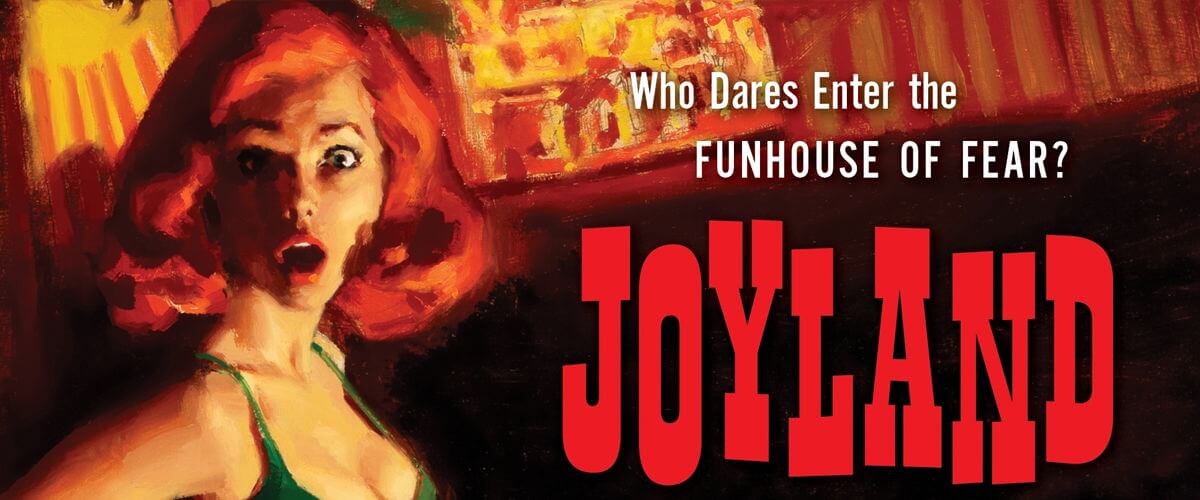

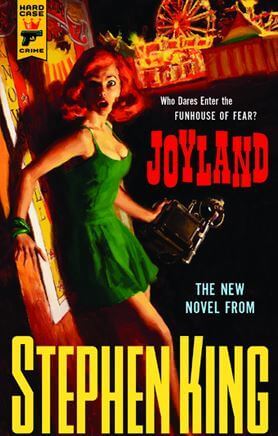

A “hard-boiled crime fiction” label dedicated to preserving and celebrating the pulpy style of paperbacks from yesteryear, Hard Case Crime specializes in reviving and discovering new works reminiscent of genre pioneers Carroll John Daly and Mickey Spillane. They publish a series of crime-themed paperbacks by new and celebrated authors, each book adorned with a vintage-style cover recalling those juicy crime stories from the 1960s and earlier. Joyland isn’t a gritty, bare-knuckled detective novel, though. There are no police, no private investigators, and no femme fatale. What the reader slowly realizes is that King has delivered perhaps his most emotionally rewarding novel in years; and moreover, he does so without resorting to one of his exhaustive page counts. In a mere 288 pages, King develops one of the most affecting, sad characters he’s ever written. Joyland may not fit all the criteria of razor sharp crime fiction, nor even meet the standards of a typical King novel, but it was a pleasure to read and recall the best efforts from his arliest work.

Set in North Carolina in 1973, this first-person paperback follows the heartbroken Devin Jones, who remembers his yearlong break from college at the titular seaside amusement park. Telling his story from an older and wiser perspective, he recalls his own coming-of-age tale as the younger version of himself is dumped by his first love and dwells in the melancholy that followed. King astutely taps into the mind of a 20-year-old man, particularly one in the 1970s (complete with Devin’s immersion into music by The Doors and Pink Floyd, and the written works of Tolkien). Between his self-pity and not-so-serious thoughts of suicide, Devin becomes a fully formed character that is more than King’s usual assemblage of clichés. Devin’s depressed worldview is contrasted by the absolute joy he—and thus the reader—discovers working at Joyland and learning King’s casually researched carny lingo. Many of the book’s pleasures come from feeling engulfed in the carny world and remembering our own early experiences at lesser theme parks similar to the one in the book.

Set in North Carolina in 1973, this first-person paperback follows the heartbroken Devin Jones, who remembers his yearlong break from college at the titular seaside amusement park. Telling his story from an older and wiser perspective, he recalls his own coming-of-age tale as the younger version of himself is dumped by his first love and dwells in the melancholy that followed. King astutely taps into the mind of a 20-year-old man, particularly one in the 1970s (complete with Devin’s immersion into music by The Doors and Pink Floyd, and the written works of Tolkien). Between his self-pity and not-so-serious thoughts of suicide, Devin becomes a fully formed character that is more than King’s usual assemblage of clichés. Devin’s depressed worldview is contrasted by the absolute joy he—and thus the reader—discovers working at Joyland and learning King’s casually researched carny lingo. Many of the book’s pleasures come from feeling engulfed in the carny world and remembering our own early experiences at lesser theme parks similar to the one in the book.

Almost tacked on to this ruminative character piece is a ghost-story-turned-mystery involving a murder at the park years earlier and the resultant urban legends about the park’s haunted Horror House ride. The park’s look-into-my-crystal-ball fortune teller gives Devin cryptic warnings, while our hero’s friends—one an amateur detective and the other a child with a second sight—guide him to a suspenseful (if predictable) conclusion. But this is secondary to the pleasures of Joyland and the carny experience. Devin gradually gets over his first love, loses his virginity, and makes himself into something of a local hero through the course of this short novel, and all of this has more weight with the reader than the “crime fiction” requirements of the publisher. Also secondary are the King-isms that his longtime readers will recognize: a ghost, a sickly child with special powers, and a chummy antagonist.

With Joyland, the adage “don’t judge a book by its cover” was never more appropriate. In this case, it’s a steamy painting designed by Robert McGinnis and Glen Orbik—a fantastic retro image to be sure, but very misleading. Such a cover creates all manner of expectations the book simply does not deliver. But it doesn’t have to. Of course, King incorporates cinematic descriptions of mild gunplay, sex, some spooky moments, and a mystery—all noirish qualities otherwise associated with the advertised genre. Beyond those isolated elements, King concerns himself with making Devin Jones a moving and at times devastatingly tragic individual, one who looks back on his life from a shrewd yet nostalgic present. Writing in a first-person style is rare for this author; King assumes a distinct voice and through it remembers better (and worse) times with fondness and sensitivity. His novel may not meet the strictest qualifications for crime fiction, but this sweet, lovingly told tale immerses us in its world and reminds us how elegant and even gentle a writer King can be.

Thanks to Titan Books for sending a review copy of the book. You can order it from Titan’s website.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review