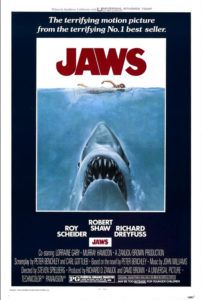

Jaws: The Shark Who Ate Too Much

By Brenda Harvieux | July 4, 2007

Many have come to interpret Steven Speilberg’s iconic 4th of July-associated film Jaws as representing the fear of the unknown—of what lurks under the waves of the vast, dark sea. This strays from sensible logic; the main characters, Brody, Quint, and Hooper, immediately realize that there is a man-eating shark terrorizing the peaceful East Coast town of Amity Island, and therefore, the “mystery beneath the waves” is far from unknown. Based on shot composition, the frenzied nature of the shark’s feeding, and the shark’s own death drive, it is clear that Jaws seeks to unveil the obsessional self-destructive nature of eating disorders, mainly bulimia—a disease very much known, but often ignored.

Many have come to interpret Steven Speilberg’s iconic 4th of July-associated film Jaws as representing the fear of the unknown—of what lurks under the waves of the vast, dark sea. This strays from sensible logic; the main characters, Brody, Quint, and Hooper, immediately realize that there is a man-eating shark terrorizing the peaceful East Coast town of Amity Island, and therefore, the “mystery beneath the waves” is far from unknown. Based on shot composition, the frenzied nature of the shark’s feeding, and the shark’s own death drive, it is clear that Jaws seeks to unveil the obsessional self-destructive nature of eating disorders, mainly bulimia—a disease very much known, but often ignored.

Bulimia is usually suffered by young women due to low self-esteem, poor body image, and can be triggered by a traumatic experience. It is characterized by an irresistible urge to binge eat and then purge the consumed food. This violence against the body leads to malnutrition, a decrease in body mass, organ failure, and if sustained, eventually death. Yet it is done voluntarily. Most often, it is left untreated because our society’s ideals, represented by the media, promote current “boney is beautiful” ideals.

The shark in Jaws is traumatized after the ship called the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) delivered the Hiroshima bomb—a haunting story retold in monologue by Robert Shaw’s Quint. When a German U-boat attacked the Indianapolis and 1,100 men went into the water, it triggered the beginnings of a downward spiral of self-abuse and binge eating via a shark feeding frenzy. The shark in Jaws was there, at the Indianapolis with Quint, and kept eating and eating, never feeling full. It made its way to Quint, but unbeknownst to both parties, Quint would be lifted to safety just as the shark approached for one last meal. The remaining 321 sailors were rescued and the frenzy was over. Was the shark not fast enough to catch Quint in time? Was his (or her—it’s never specified) girth too pronounced after gulping down who-knows-how-many sailors? Perhaps the shark’s weight prevented itself from another meal. Unable to answer these questions, to fill its void, the shark began to blame Quint (classic transference), vengefully thinking of him as “the one that got away.” A period of self-loathing followed in the shark, hatred for itself, its body, and Quint.

Unable to control its hunger, the shark begins eating humans. Though these attacks seem random (a young woman, a dog, a boy, etc.), the shark is aware his feedings attract attention; its own suicidal death drive takes over, hoping someone, which ironically turns out to be Quint, will try and put it out of its misery. As the attacks persist, the mayor of Amity Island purposefully ignores the problem in order to preserve the beauty of the locale. This parallels society’s choice to ignore the growing epidemic of deathly skinny women in the media and our home communities, thus finally declaring that their lacking forms are beautiful, hence devaluing any mental issues that could account for their negative bodily self-images.

Juxtaposed by the three main characters—all of which are male—the shark in Jaws becomes effeminized; the shark becomes the vagina dentata, or vagina with teeth. In the eyes of the male characters, the shark seeks to castrate them with its powerful and renegade jaws, and the only conclusion they can reach is to destroy it instead of acknowledging the social problem it represents. In admitting that they implemented the system that supports negative self-images, they would be castrating themselves.

Speilberg shows his sympathy for those who suffer from eating disorders similar to the shark’s by allowing the audience to identify with it in the first scene of the film. When Jaws begins, Speilberg uses a point-of-view shot to suture the viewer to the shark; we are meant to see things from its standpoint and sympathize with those who oppose it. Often in films where there is an attacker/attackee relationship; the camera focuses on the attackee, placing the audience in the shoes of the attacker. Throughout most of Jaws, only a small part of the shark appears on the screen; a shadow here and a fin there allows the viewer to recognize their relationship to the central character in the film: the shark. Then, during the feeding attacks, our attention is focused on the human being eaten. We see what the shark wants us to see. We become the shark, driven to madness by a ravenous hunger, yet revulsion to digest.

Speilberg shows his sympathy for those who suffer from eating disorders similar to the shark’s by allowing the audience to identify with it in the first scene of the film. When Jaws begins, Speilberg uses a point-of-view shot to suture the viewer to the shark; we are meant to see things from its standpoint and sympathize with those who oppose it. Often in films where there is an attacker/attackee relationship; the camera focuses on the attackee, placing the audience in the shoes of the attacker. Throughout most of Jaws, only a small part of the shark appears on the screen; a shadow here and a fin there allows the viewer to recognize their relationship to the central character in the film: the shark. Then, during the feeding attacks, our attention is focused on the human being eaten. We see what the shark wants us to see. We become the shark, driven to madness by a ravenous hunger, yet revulsion to digest.

In the finale, the shark eats Quint, believing that “the one that got away” will finally appease its appetite. When the shark swallows Quint, it realizes its emptiness of stomach is akin to its vacant heart and soul. Realizing this self-reflective penultimate truth, its death drive takes over; suicide becomes the only answer. It leaves Brody and Hooper alive so they might kill it, and even entices Brody to do so. The shark attacks the sinking boat, crashing through the side and lunging at Brody. With its powerful jaws and general massiveness, the shark could have easily snatched Brody and eaten him. Yet it did not; instead, the shark motions to a tank compressed air in order to draw Brody’s attention to it.

Sharks are known to spit out food unsavory to them, so the fact that the shark keeps the tank in his mouth is significant. It backs away from the boat, allowing Brody to prepare. When Brody tosses the tank into the shark’s mouth, it is not swallowed, but shown in the shark’s mouth pointedly as a vulnerability for Brody to exploit. Brody fires a few shots, and when he is unsuccessful, the shark swims closer, eager to meet the eternal darkness of the deep. When Brody’s bullet pierces the air tank, the shark explodes, and his chunky red fog becomes one with the sea, ironically food for hungry little fish.

Clearly, this film is not about the fear of the unknown, but rather, the tragic tale of a self-loathing creature suffering from an eating disorder. So, this 4th of July when you plop down in front of your television to watch Jaws with a plate full of grilled meat and anti-pasta salad, dive a little bit deeper into the story: do not just accept what is on the surface.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review