Instant Homogenization

By Brian Eggert | November 10, 2015

Moviegoing isn’t limited to theaters; the home theater, too, is a form of moviegoing today. A considerable number of viewers watch movies almost exclusively from the comfort of their own home or on a device. They may see a mere handful of films in the theater per year, while their other viewing is done through subscription-based streaming services or television. But the variety of content available to audiences via these streaming services is limited. Over 300 films are released each year theatrically by U.S. distributors, not including hundreds of releases from the international market, plus even more on VOD-only or direct-to-video distribution deals. But only a small fraction of that number ever arrives on unlimited streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu, and AmazonPrime—each of which charge a nominal fee for access to their small library of titles.

In my experience, people rarely venture outside of these most popular services. More often than not, people will only watch movies on their current streaming plan. Recently, I asked someone, “Have you seen The Bridge on the River Kwai before?” The person responded, “Is it on Netflix?” I explained that it was not. The person shrugged, as if there was no other option. But of course there is. The Bridge on the River Kwai is indeed available on Netflix, should you choose to use their disc plan. However, so few consumers bother with discs nowadays. (Another option: you can go the less popular route of paying for a rental on AmazonPrime or Vudu.) As a result, viewers who select streaming-only options limit their choices to what companies like Netflix, Hulu, and AmazonPrime are offering.

In my experience, people rarely venture outside of these most popular services. More often than not, people will only watch movies on their current streaming plan. Recently, I asked someone, “Have you seen The Bridge on the River Kwai before?” The person responded, “Is it on Netflix?” I explained that it was not. The person shrugged, as if there was no other option. But of course there is. The Bridge on the River Kwai is indeed available on Netflix, should you choose to use their disc plan. However, so few consumers bother with discs nowadays. (Another option: you can go the less popular route of paying for a rental on AmazonPrime or Vudu.) As a result, viewers who select streaming-only options limit their choices to what companies like Netflix, Hulu, and AmazonPrime are offering.

In turn, these streaming services narrow your tastes as a viewer, giving you access to only a small percentage of the titles out there. Viewers are more apt to accept whatever these companies feed them rather than seek out what they really want, resulting in a homogenized population of moviegoers with very limited and unversed viewing chops.

What You’re Watching

Each streaming company partners with various distributors and works out a licensing deal for certain movies and TV shows, thus controlling what’s available to you. This deal allows Netflix and others like them to showcase the content, in some cases exclusively. However, the selection often includes less popular titles and rarely consists of new releases. The few newer, popular titles that do hit streaming services arrive only after the physical media option (Blu-ray, DVD, etc.) has been available to generate sales for a few months.

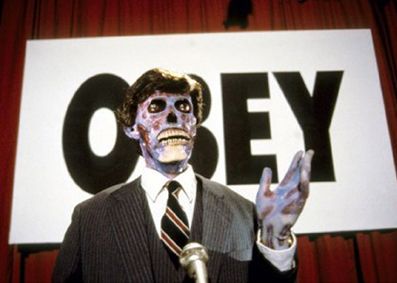

Fortunately, smaller distributors like IFC Films and other independent labels happily stream their inventory on Netflix and other on-demand providers. After all, their lower-budget releases have always struggled to reach larger audiences. Viewers who would never think of watching these so-called “indie” titles now have access through Netflix and companies like it, which is great. But there are other, smaller titles that overwhelm Netflix’s inventory, the majority of them lousy B-movies (Killer Mermaid, anyone?) and dramas barely worthy of cable television—movies that couldn’t secure theatrical distribution and perhaps debuted on VOD, or even worse, debuted on a streaming service. This direct-to-video garbage floods every title and genre search on almost every streaming service.

Fortunately, smaller distributors like IFC Films and other independent labels happily stream their inventory on Netflix and other on-demand providers. After all, their lower-budget releases have always struggled to reach larger audiences. Viewers who would never think of watching these so-called “indie” titles now have access through Netflix and companies like it, which is great. But there are other, smaller titles that overwhelm Netflix’s inventory, the majority of them lousy B-movies (Killer Mermaid, anyone?) and dramas barely worthy of cable television—movies that couldn’t secure theatrical distribution and perhaps debuted on VOD, or even worse, debuted on a streaming service. This direct-to-video garbage floods every title and genre search on almost every streaming service.

Rare are Netflix Originals that bring an artful or otherwise unique product to a mass audience. Just this October, Netflix debuted their first original feature production, the very well-reviewed Beast of No Nation starring Idris Elba, from writer-director Cary Joji Fukunaga. It’s about the not-audience-friendly subject of a warlord who trains children into his army. Netflix has said it’s planning more original content and feature films; these include a 6-picture-deal with Adam Sandler, a couple of titles produced by Brad Pitt, and a new mockumentary by Christopher Guest. Netflix also offers plenty of excellent original shows, including House of Cards and Daredevil. Amazon and Hulu offer some nice original content as well.

And while much of this original programming takes more risks than your average network show, the sheer volume isn’t enough to compete with (what would/should be) a full inventory of recognizable streaming catalog titles.

What You’re Not Watching

Indeed, the streaming moviegoer’s options are getting narrower all the time. For example, at the end of September, Netflix ended a five-year deal with Epix (comprised of MGM, Lions Gate Entertainment, and Paramount Pictures). This deal allowed viewers access to big Hollywood titles from World War Z (2012) to The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and everything in-between. These particular titles went to Hulu. But if you don’t use Hulu, to watch these titles now you would have to rent a streaming copy from AmazonPrime or Vudu for a small fee. Or buy them in a physical media format (renting in a physical format is a virtually Netflix-only prospect, aside from Redbox and a few other vendors).

No matter how much original programming these streaming companies offer, viewers have less variety than if their favorite streaming service licensed more titles from the studios. Good luck finding major blockbusters or a thorough catalog of classic cinema on these services, unless they happen to be owned by one of their few studio distribution deals. Whether it’s because major studios aren’t getting the attention they want on streaming services, or because the streaming services are avoiding such deals to escape the associated costs, audiences suffer.

No matter how much original programming these streaming companies offer, viewers have less variety than if their favorite streaming service licensed more titles from the studios. Good luck finding major blockbusters or a thorough catalog of classic cinema on these services, unless they happen to be owned by one of their few studio distribution deals. Whether it’s because major studios aren’t getting the attention they want on streaming services, or because the streaming services are avoiding such deals to escape the associated costs, audiences suffer.

To be sure, licensing is a costly process for streaming companies; it’s more profitable for them to create their own, limited content. Not every studio partners with each streaming service, and those who do only offer a limited number of titles. In some cases, a consumer must use 3-4 different services, if not more, to access everything they want. And so, you get the illusion of variety with these streaming services, nothing more. This is why viewers can waste countless minutes scrolling through the not-so-boundless streaming inventory, trying to find something of quality to watch. Meanwhile, as countless minutes—hours even—are spent trying to find something worthwhile to watch, we could be getting what we want from another service.

Your Solution

To quote Bane in The Dark Knight Rises, “Take control!” Assume responsibility for your viewing. Figure out what you want and seek it out. These companies are telling you what to watch. Remember, there are hundreds of films released each year, and thousands of titles from years past. Don’t create a viewing wall for yourself by simply accepting the boundaries of Netflix or AmazonPrime.

And so, what do you do when there’s a movie you want to see, but it’s not yet on a streaming service? One of the best resources for movie diversity is Netflix’s disc plan. It may not be streaming, but they carry almost everything. The shipping is overnight in most cases. And because fewer people are using this service today as opposed to ten years ago, there are fewer “long wait” times. Although some new releases are delayed a month or more after their initial physical media release date to allow for disc sales, the rental release is worth the wait for a title you want. Or, if you’re a classic or art movie buff, check out Hulu. The Criterion Collection offers over 500 of their “important contemporary and classic” films through Hulu’s streaming service. Truth be told, there’s not one perfect option for you to see everything you want. It’s a sad reality that you may have to use 3-4 streaming services to see everything you want to see.

And so, what do you do when there’s a movie you want to see, but it’s not yet on a streaming service? One of the best resources for movie diversity is Netflix’s disc plan. It may not be streaming, but they carry almost everything. The shipping is overnight in most cases. And because fewer people are using this service today as opposed to ten years ago, there are fewer “long wait” times. Although some new releases are delayed a month or more after their initial physical media release date to allow for disc sales, the rental release is worth the wait for a title you want. Or, if you’re a classic or art movie buff, check out Hulu. The Criterion Collection offers over 500 of their “important contemporary and classic” films through Hulu’s streaming service. Truth be told, there’s not one perfect option for you to see everything you want. It’s a sad reality that you may have to use 3-4 streaming services to see everything you want to see.

The point is, don’t reduce your viewing habits to the programming offered by these streaming services. A lot of talk with friends and acquaintances about movies has descended into chats about what this or that person has “Netflixed” recently. Aside from it being annoying that Netflix has become a verb, it’s more annoying that people have tunnel vision when it comes to what’s available to them. They aren’t seeing great movies they should because Netflix, and services like them, aren’t yet and maybe never will offer them as free streaming. It makes for boring movie conversations and, frankly, boring people. So, as I said, take control. There’s a wealth of great material out there, and unless you’re searching for it outside of the realm of these streaming services, you’re probably missing it.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!