The Definitives

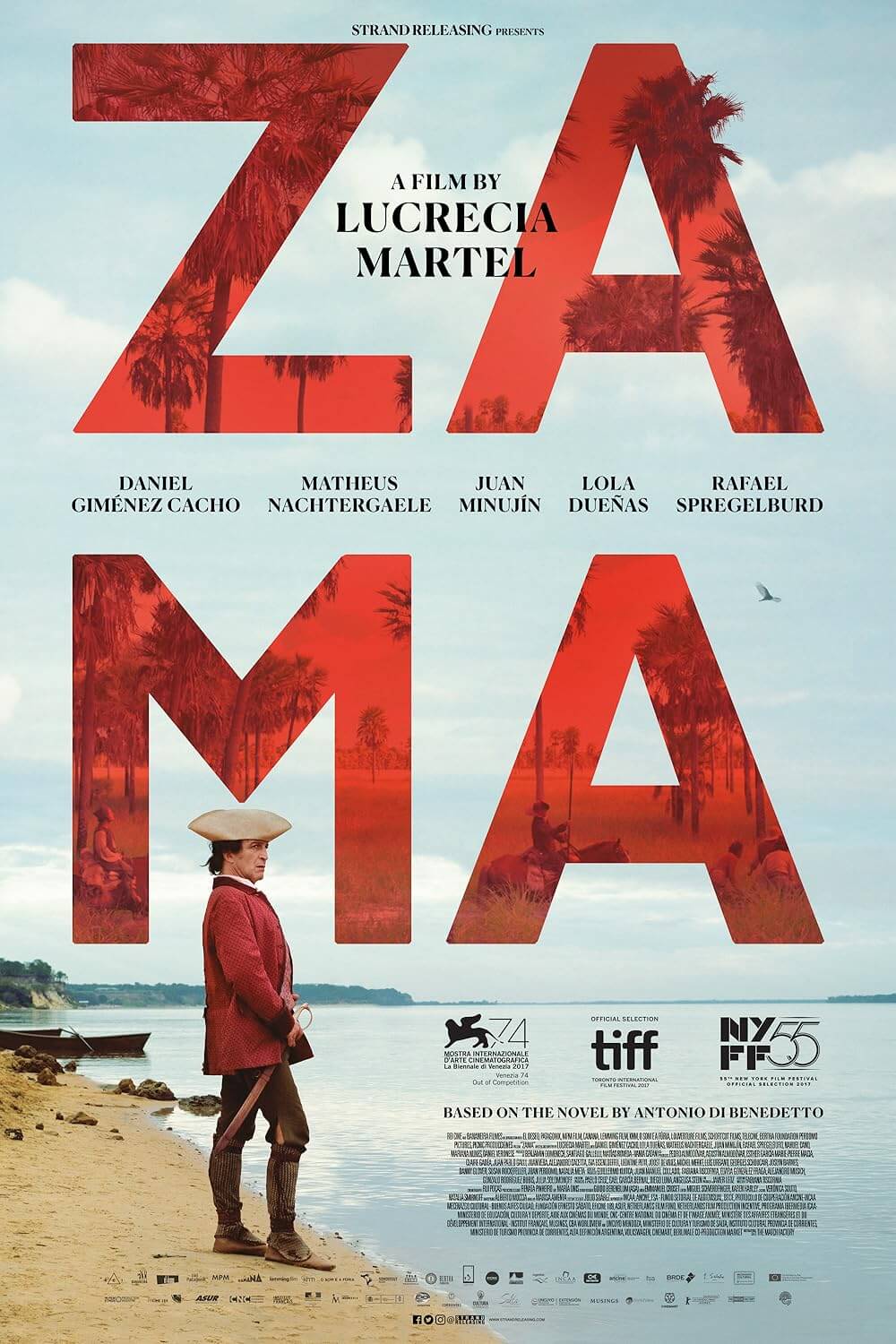

Zama

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Lucrecia Martel’s Zama opens with an image evoking wonder and contemplation. Don Diego de Zama, a Corregidor in the Spanish Empire, stands on the coast of the backwater Argentinian colony where he resides. He looks out at the expanse, tortured and yearning. His wife Marta and their children live far away, in Lerma, situated in Argentina’s Salta region, and she will remain at an eternal distance. In his current station, career advancement and decorations from his imperialist bureaucracy are nothing more than dreams. At this moment, he gazes outward as some native boys play behind him. Zama refuses to engage them, putting himself at a distance; and yet, he’s drawn to them. He glances over several times, keeping a respectable distance. He wants to be noticed and included. However, Zama will never achieve a noble career or a meaningful connection to the people of his birthplace in the Americas due to his own conceit. He resolutely sees himself as Spanish, even though the European-born representatives from Spain that rule the colony consider him a local. But the locals view him as an outsider, a representative of the Spanish colonists. He subsists in a perpetual state of isolation, removed from his country and the country he aspires to be a citizen of, leading to his nine years of inward deterioration that unfold before us. Zama‘s opening shot places its protagonist at the very point where the ocean touches his feet, a symbolic space between the colonized and its empire across the ocean.

Don Diego de Zama might be a metaphor for Martel’s films, which have a languorous poetry and inhabit the elusive space between the shown and not shown. None more so than her fourth feature, in which the Argentinian director employs formal techniques that investigate a displaced character. Zama is a symbol of the multifaceted nature of modern Argentinian identity—to some extent, the subject of every Martel film. With Zama, she creates a cinematic experience that, for those unfamiliar with Antonio Di Benedetto’s source novel, will prove equally confounding and hypnotic, if exhilarating for the sheer artistry on display. While the film echoes the style of Di Benedetto’s novel, the two pieces complement each other, revealing a curious relationship between the texts and their respective authors, Martel and Di Benedetto. Both use colonialism, unreliable narrators, fantasticism, isolation, sexual desire, Nature, and narrative ambiguity in ways that entrance their reader and inform their beleaguered protagonist. Its adaptation to the screen reveals an aching, comically cruel internal nightmare that portrays the novel’s first-person singular world—not with subjective camera angles or other such formal devices, but through its director’s intuitive, mesmeric immersion into the world in which Don Diego de Zama languishes.

Di Benedetto’s novel was first translated into English in 2016 by writer and translator Esther Allen—whose scholarship and writings about Zama inspired and informed this essay—just a year before the film’s debut in Argentina. Born in 1922 to Latin American parents of Italian descent, Di Benedetto spent much of his early life in his birthplace of Mendoza, Argentina. Although his first writings were for a local newspaper, he began writing fiction in 1953 with the publication of Mundo animal, a collection of short stories. As Allen observes, Di Benedetto felt like a man out of time, that he should have been born in the previous or subsequent century. He felt isolated, and he isolated himself—he intentionally kept away from Argentina’s cosmopolitan epicenter of Buenos Aires, a decision that limited the potential for his work to achieve notoriety in literary circles. His first novel was Zama, published in 1956, and he followed it with several others. The author’s efforts brought him little attention at the time, though later, his work would earn him several honors, among them accolades from the French and Italian governments. Somewhat isolated from the Latin American writers of his time, Di Benedetto has a similar trajectory to authors such as Franz Kafka, Herman Melville, and Edgar Allen Poe in that critics and scholars reassess his work only after his death. He remains largely unknown in the United States outside of scholarly circles or those compelled to learn more about Martel’s film.

In 1976, at the outset of the Dirty War—between Argentina’s military dictatorship and the left-wing opposition that was devoted to stopping the insurgence of secret police, disappearances, and civil rights violations—Di Benedetto was arrested, imprisoned, and tortured for reasons that he never learned. It may be that his journalistic integrity and refusal to alter his reports according to the demands of military generals who incited the Dirty War caught up with him. On several occasions, he was dragged before a firing squad, read his death sentence, and told he would die. Suffering through a mock execution famously shaped Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who experienced a similar threat of trial and execution in 1849, and Di Benedetto often associated himself with Dostoyevsky in relation to his political persecution and writing style. And while Di Benedetto wrote Zama long before his torture at the hands of the military dictatorship, the author’s life seems fraught by his closeness to death, whether it be his pride about his birthdate on the Day of the Dead, his uncertainty about the reasons for his imprisonment, or his self-imposed geographical isolation in Mendoza, and thus the literary community—all qualities present in the novel and, further, Martel’s film. After his release from imprisonment in 1977, Di Benedetto fled to Spain, where he remained in exile before returning to Buenos Aires in 1984, following the restoration of democracy in 1983. He died less than two years after his return to Argentina at the age of sixty-four.

Di Benedetto’s life and work reflect one another, in that he wrote about and experienced isolation in the early part of his life. To describe places in Zama outside of his home base in Mendoza, places he would not visit until long after the book’s publication, he carried out research to achieve an accurate representation of the location and period. Di Benedetto’s book is structured into three dated sections (1790, 1794, 1799) over nine years, and to portray them, he sought historical descriptions logged by a Spanish traveler from the period. Contemporary sources also influenced Zama. He was particularly drawn to the biography of Dr. Miguel Gregorio de Zamalloa, written by Efraín U. Bischoff in 1952, about a Corregidor not unlike Zama—an Americano serving as a chief justice in what is present-day Bolivia, who was forced to remain in his unhappy post, waiting fourteen years until his transfer in 1799. But Zama resists the traditions of the historical novel by occupying its protagonist’s perspective in the first-person singular—a perspective that, by contrast, occupies a distinct twentieth-century viewpoint. This has a disorienting quality that enhances the reader’s sense of Zama’s isolation, in that Di Benedetto writes the character so that the reader can interpret how misguided, deluded, and off-base Zama often is in his thinking. Like many Latin American authors of his day, Di Benedetto set out to subvert authority, and his novel does that by unraveling the classical, romantic period drama in its focus on a petty, racist, ineffectual man.

Similarly to Di Benedetto’s devotion to the history and people of his birthplace in Mendoza, Martel began her career with three films set in Salta, her provincial hometown—a city removed from the comparatively cosmopolitan Buenos Aires, Argentina’s capital. Each film in Martel’s Salta Trilogy—La Ciénaga (2001), The Holy Girl (2004), and The Headless Woman (2008)—concerns the gap between the rich and the poor, the class divide between the privileged descendants of colonial imperialists and the natives. Her socially entitled characters demonstrate their everyday dismissal of the lower classes, even while grappling with and ultimately suppressing any latent guilt over Argentina’s violent history of colonialism and political strife. Formally, her work employs a mysterious use of visual space, temporality, and sound: What appears onscreen is sometimes less important than what is unseen; edits often remove vast periods of time; and her use of a heightened sound design points our attention to seemingly minute aural details, focusing our attention on its visual source, or lack thereof. As David Oubiña observed, “Martel treats filmmaking as a subtractive process and the film as a reduction, though what she excludes remains in the suburbs of the image, troubling what we see.” Given her mastery of form and the power of her subject matter, Martel played a significant role in gaining attention to the wave of New Argentine Cinema that began in the 1990s, and further, Latin American cinema in general, while drawing the attention of notable international producers (Pedro Almodóvar, Gael García Bernal, and Danny Glover) who would support her work.

Zama comes after a nine-year hiatus in Martel’s career following The Headless Woman. In the interim, Martel tried to make a science-fiction epic, although her trio of small, underseen previous efforts, each about colonialism to some extent, undoubtedly failed to demonstrate to investors that she could manage the bigger budget and assured commercial returns required for sci-fi. It would have been a significant departure from her experience thus far, but she sought the challenge out of a readiness to test herself as a filmmaker. She wanted to adapt El Eternauta (The Eternaut), an Argentine comic strip published between 1957 and 1959 by writer Héctor Germán Oesterheld and artist Francisco Solano. It followed a Buenos Aires family that escapes an alien invasion only to be sent reeling through time, space, and eternity. In earlier films, Martel portrayed the modest setting of Salta, a place with which she was familiar; with El Eternauta, she wanted a chance to create an entire cinematic world onscreen. She began working on a script and even consulted Industrial Light & Magic about the possibilities of special FX, but the project inevitably fell through in 2009. Shortly after that, she was given Di Benedetto’s novel and, much like a work of science-fiction, Martel recognized an other-worldliness in the author’s use and choice of words that situate Don Diego de Zama on another planet of his own making. Martel recreates that planet in Zama, making it a unique breed of science fiction.

Stuck in a remote village, Don Diego de Zama, played by Spanish actor Daniel Giménez Cacho, hopes for a transfer to the Lerma Valley—the modern-day Salta, Martel’s home—where his wife and children wait for him. Although he maintains a position of power, second only to the Spanish-born governor, he’s in the middle of nowhere, and his transfer requests have a way of being ignored. Worse, the imperialist administration continues to delay wages, leaving Zama destitute, dejected, and alone. Given Zama’s oblique existence, every moment in the small town feels enhanced by sensory embellishments from Martel’s direction. Her enhancements of sound or inclusion of visual cues that do not belong in an eighteenth-century South American location, emerge slyly and without undue attention drawn to their presence in the film. They’re merely a part of the film’s world, even as their presence causes disassociation, and they reflect Zama’s status as a man out of time. Di Benedetto wrote so the reader could gain some appreciation for the variance between the world and how Zama perceives it; in the film, that distinction is trickier. Without using subjective camera angles, a film’s perspective relies on something more elusive than, in Di Benedetto’s case, the first-person singular mode of storytelling. Martel does more than merely translate the film to the screen. She portrays Zama’s world in all its imbalance, adding off-kilter touches to create a sense of disassociation, thereby demanding the viewer identify elements divorced from a representation of the real world.

Then again, Don Diego de Zama is external and separate from his surroundings, partly out of choice. He is defined, or rather defines himself, by his lineage as a Criollo—a person of full Spanish descent born in the New World. Though he’s never stepped foot on Spanish soil, he carries the austere behavior and pretense of European nobility. “Europe is best remembered by those who were never there,” he’s reminded at one point. Unlike many of the Spanish superintendents of their colonies, Zama was not born, raised, and educated in the Spanish motherland. Thus he remains a strange incongruity in the usual organization of Spanish colonialism in the Americas. In fact, he should not be there at all. Spanish rulers often enforced a policy that Creoles could not hold positions of power, regardless of their bloodlines, because they may begin to identify too much with their other Argentinian-born nationals. In the nineteenth century, Creoles led the revolutions against their Spanish colonizers and achieved independence for many South American countries. With this in mind, Zama’s relationship with his three governors throughout the film suggests that they see him more as a member of the colonized than the colonizing party. Each of the governors treats him with shame and disrespect—such as the first governor (Gustavo Böhm), who removes Zama’s furniture during an audit, forcing him to live in veritable squalor. Or the second governor (Daniel Veronese) who, after forcing Zama into a prolonged series of humiliations, finally agrees to write the king for a transfer on Zama’s behalf, and then adds that the process could take years.

Apart from his pedigree, Zama invites humiliation from those around him. He always tries to say the polite and noble thing, to carry the manner of a Spanish nobleman, but his manner always seems desperately artificial. Martel accentuates his foolish presence in one scene by placing a rogue llama in the backdrop, as if to associate Zama with the roaming, laughable-looking animal. He attempts to be gallant, such as when he chases away an intruder at the inn—there to bed Rita (Paula Grinzpan), the innkeeper’s daughter. But his heroism is unfounded, as clearly Rita and the other daughters were in league with their mysterious inamorato. Moreover, Zama uses the incident as an excuse to make an embarrassing and unrequited pass at the supposed victim. The locals assume the intruder was Vicuña Porto, a famed criminal referenced throughout the film and assigned blame for virtually every unsolved crime in the area. Vicuña Porto has “died 1,000 times” in various executions, yet he always seems to return and commit another crime. The fabled bandit appears only in the final section of Di Benedetto’s book, but Martel establishes his legend early in the film as an almost mythical presence. As others in minor bureaucratic positions view Zama as pathetic for his superior attitude, they mock him for putting on airs or claiming to have nearly captured Vicuña Porto. When he tries to beat an underling for his insolence, the man can only laugh. “Such bravura! They say you almost captured Vicuña Porto,” the man says derisively.

Given his Spanish bloodline, Zama perceives such insults as gross personal injustices against his sense of racial superiority over many of the local people—descendants from the rampant history of Spanish conquistadors reproducing with native women. He is obsessed with racial purity and, on one occasion early in the film, briefly mentions that he prefers Spanish women, women of white skin, and refuses the opportunity to sleep with a native prostitute. But similar to the conquistadors who kept several native wives as their personal harems, Zama does not limit himself to the memory of Marta and abstain from sexual relations with local women. He pines after a member of the Spanish-blooded nobility, Luciana (Lola Dueñas), the Treasury Minister’s wife, who toys with him and obviously never intends to take Zama seriously as a romantic prospect. People in the village mock Zama’s obvious infatuation, remarking that Luciana has “the most beautiful body that Don Diego de Zama has never touched.” The meetings between Luciana and Zama reveal a toying flirtation on her part, as she’s careful to keep an attendant in the room at all times, knowing Zama would never advance in another’s presence. And yet, she keeps him interested, perhaps out of scorn, when she tells him, “You deserve a kiss” before adding, “Not now.”

At the same time, he remains hypocritical about his own racist pretensions toward sexual conquests. On the side, Zama has fathered an illegitimate child with a native woman and, instead of pursuing a transfer to rejoin Marta, he seeks to legitimize his son by enlisting the governor to write a letter to the Spanish king. But the boy’s native mother is uninterested in marriage or titles for their son, and she ridicules Zama for assuming there’s any obligation between them. Perhaps more succinctly, an early scene shows Zama spying on a group of mud-bathing nude women near the beach. One of them spots him, shouts “Voyeur!” and chases after him. Filled with shame, he runs, before realizing he can exploit the situation: he slaps the woman down, relying on his status as a Corregidor to justify his actions. Martel has explored these themes since her debut, La Ciénaga, in which the classist Mecha looks down her nose at the native servant class she decries as lazy, despite having resigned herself to the life of a bedridden wino. There’s evidence in The Holy Girl as well, as the young Amalia desires piousness, yet she cannot help but find herself drawn to a frotteurist doctor. In Martel’s films, sexual desire remains in conflict with outward, repressive sociopolitical ideologies, revealing such views as sanctimonious.

Zama exists outside of his community. Despite his title, he bears no significant social status in his local government, and his imperialist leaders remain indifferent to his presence, given his birthplace in Argentina. And though he was born in their country, the natives and other Creoles view him as an outsider, a symbol of the Spanish imperialists. He furthers his isolation by refusing to have sexual relations outside of his race, a viewpoint mocked by everyone on both sides who gladly participate in interracial sex. With these dynamics in mind, much of what occurs in Zama could be interpreted as a punishment of the antihero protagonist for his allusions of so-called purity. Whether by the Fates, the Cosmos, a god-figure, or by his own making, the source of these corrective actions remains unclear. It’s worth noting that Martel removes any sign of Christianity otherwise present in the book, and hugely influential on the historical setting, which brings into question why such symbols have been extricated from her film. Perhaps this is a way of showing that Christianity has no place in Zama’s mind, or that his views betray not Christian ideals but represent political and social crimes. In any case, throughout Zama, it’s as though events occur to keep the character in his solitude: his regular denials for a transfer, his constant humiliation, and his inability to feel included. He almost earns our sympathy as a victim of his own perspective, as Martel’s treatment blends a pitch-black comedy with a sensory nightmare.

Martel’s formal methods of showing Zama’s isolation entangle the viewer in his perspective, most notably as she and sound designer Guido Berenblum create a disorienting soundscape. At all times, the viewer is acutely aware of diegetic sounds occurring off-screen: insects buzzing, children scampering, hammering from the construction in town, birds chirping, horse hooves galloping, dogs barking, and a million other insuppressible aural details that seem to trap Zama in his current position. The omnipresence of sound is both perplexing and confining; it refuses to be ignored, as though Zama endures in a perpetual state of discomfort, never settling in or growing comfortable with himself in the surroundings. Non-diegetic sounds also play an imperative, hallucinatory role in the film. During scenes when Zama is denied a transfer, or when it seems as though he might be on the right path but then experiences an overwhelming setback, Martel and Berenblum use tonal descensions that bring to mind a plane falling from the sky. The tone overwhelms these scenes as the dialogue drops away, signaling Zama’s emotional devastation, and then all at once, Zama is jolted back into reality. At the same time, Zama’s score provides a bemused commentary. Listen to the guitars of the Brazilian group Los Indios Tabajares, which evoke thoughts of Elvis Presley’s album Blue Hawaii or Santo & Johnny’s entrancing “Sleep Walk.” The contrast between 1950s Hawaiian vacation music and Zama’s dire, hopeless situation is a caustic flourish.

If the sound and music in Zama prove anachronistic to the period, it’s another indication of Martel’s inventive uses for history and time. Her approach provides a commentary, expanding on the text to make Don Diego de Zama’s story something far more bewildering, funny, and even horrifying. Di Benedetto’s use of temporality was influential for its outward appearance as historical fiction, juxtaposed by its massive omissions of the character’s life. Martel creates a less tangible notion of time in her film. Whereas Di Benedetto signaled transitions that leaped years forward with each section of the novel, from 1790 to 1794 to 1799, no such transitions occur in Martel’s film. Time unfolds over the same period but without titles to indicate the shifts. Between cuts, months or years may have passed, and only through our observations of Zama’s appearance does the passage of time become evident. He looks increasingly disheveled as the film carries on and the years pass. His hair suddenly appears grayer, or his skin has wrinkled in a way it wasn’t in the previous scene. In the final section, circles appear under his weary eyes, his skin is cracked and pale, and he has a lengthy beard, suggesting he’s given up on any hope of escaping. A single clue in the film reflects the book’s triptych structure: the presence of three governors overseeing Mendoza indicates the period of years between Spanish colonial rulers in this small Argentine town. And yet, all the while, Zama maintains his air of European superiority, an aspect of his personality emphasized and exaggerated by Martel as time elapses.

As Martel resists the three-part structure of Di Benedetto’s book, she creates an experience unique to cinema—whereas a book can be set down and returned to—that accentuates the material’s sometimes unearthly moments. Zama’s ambiguous timeline is marked by inclusions that seem to betray the historical setting, making the film even more disorienting, entering it into the realm of the fantastic. In the same way that the book employed contemporary turns of phrase like “mental checklist” that did not exist in the story’s setting, making it a postmodern work in a classical environment, Martel incorporates details uncoupled from an eighteenth-century Argentina. During a sequence late in the film, Zama and a small militia head into the wild to hunt down Vicuña Porto. A group of natives, painted in red and feared by the posse, confronts them. They force Zama and his party into a metallic chamber that has no place in this historical context. The room evokes thoughts of an underground gas chamber or steam room. The sharp cutting throughout the sequence—itself a departure in a film of unhurried rhythm—makes it impossible to identify. But the sounds of metallic doors slamming and tinny echoes of voices against the room’s walls suggest a space outside of anything rational or known in this historical context.

Although it’s tempting to lump both Di Benedetto and Martel’s versions of Zama into the critical category of magical realism, given how both deploy aspects that have no foundation in the historical reality of the setting, a distinction between magical realism and Martel’s feverish storytelling here must be made. The comparison is understandable since, as a critical term, magical realism (or lo real maravilloso) emerged in Latin American literature in the mid-twentieth century as a postmodern trend to critique conventions, question notions of the rational and real, and explore politics and religion through their collision with fantasy. Such stories blend a fantasy element into a realistic setting and, together, those elements exist in the same narrative space. Many of Di Benedetto’s contemporaries, such as Jorge Luis Borges or Gabriel García Márquez, explored this genre as a collocation of an established history and the novels designed to subvert those histories. Many drew inspiration from Franz Kafka’s 1915 novella The Metamorphosis. Kafka comments on society and family through a fantastical metaphor when his protagonist, Gregor Samsa, transforms into a large insectoid. Within the reality of Kafka’s story, Samsa has actually metamorphosed into a bug. Latin American writers of Di Benedetto’s period introduced similar elements into their stories as a form of narrative commentary. Colloquial uses of the term magical realism today differ from Di Benedetto’s time, in that it now occupies an entertainment genre of unassuming landscapes or gritty urban settings that find themselves intruded upon by figures from myth and fantasy in a genre mash-up style. Guillermo Del Toro, for instance, has followed in that tradition with The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and The Shape of Water (2017).

By contrast, Di Benedetto and Martel operate in ambiguity, creating a distinction between their approaches and those of magical realists. Their narrative treatment occupies the subjectivity of the protagonist in the same way that, say, the writing of Miguel de Cervantes did in his respective masterwork. Cervantes wrote Don Quixote in 1605 and, in his blend of realism and fantasy, he acknowledged that his hero experienced a delusion in the form of fantastical elements that appear in the story. Quixote saw windmills that were not there within the text of the novel, and the hero’s delusions served as an interpretable commentary by the author. In both the book and film of Zama, elements that seem transcendental or uncanny could be, and probably are, the protagonist’s imagination getting the better of him. Di Benedetto and Martel embrace this type of distorted subjective viewpoint, whether by their mutual commitment to describing the world through Zama’s eyes, or the film’s formal ambiguity—its vague temporality or unnerving use of sound and silence. The misplaced elements of Zama’s world occur in his mind or, in the case of the film, Martel’s representation of it.

In Martel’s devotion to and directorial elaboration on her character’s subjectivity, time fades in hypnotic ways because it is experienced as a blur in Zama’s life. His interaction with the red-painted natives plays like science-fiction because it’s a fearful experience in an unfamiliar setting. The viewer of Zama, therefore, remains unclear about the events and their place in the story’s world. This approach is not a continuation of the Latin American affinity for magical realism, not a blend of the fantastical with a harsh reality, but a convergence of the protagonist’s imagination colliding with his cruel reality, creating an unreliable narrator. As Esther Allen points out in her introduction to the novel, comparisons between Zama and The Metamorphosis remain fitting, if not essential, but Zama is “a negative image of Samsa.” Zama has been separated from his family; Samsa is confined to his room by his family. Even their names sound similar, as the letter z in the Spanish pronunciation around Argentina has an s sound, so Zama sounds like Sama. Journalists and critics in Di Benedetto’s time asked him about these comparisons, and he admitted that he read The Metamorphosis the year before publishing Zama. Consequently, it’s not difficult to see the influence of Kafka on Di Benedetto, given that both Samsa and Zama are characters undone by some combination of an oppressive society and their own stubborn worldview. But the influence of magical realism on Di Benedetto’s book, and by extension Martel’s film, does not align it with that category. Zama is far more ambiguous and ominous about what’s really happening and what isn’t.

The film’s ending is a confluence of reality and Zama’s identity catching up with him. Amid their search for Vicuña Porto, one of the soldiers, traveling under the name Soldado Gaspar Toledo (Matheus Nachtergaele), admits he is the famed rogue in disguise. “The Vicuña Porto they talk about doesn’t exist,” says the rather diminutive man. “It’s no one.” Neither does Don Diego de Zama exist, at least, not in the way he projects himself. While tall tales have exaggerated Porto’s identity, Zama’s identity is self-authored, but both are equally fabricated. Out of terror and self-preservation, Zama keeps Porto’s true identity a secret, until the perilous journey becomes too much to bear. When the mission’s commander refuses to return without Vicuña Porto in chains, Zama quickly exposes the infamous bandit, hoping to overtake him and finally return home. Instead, Porto and his followers torture the commander to death and then proceed to chop off Zama’s hands, leaving him for dead. It’s all the more ironic and horrifying that Porto’s group searches for “cocoanuts”—their word for precious stones that are, in fact, worthless amethyst geodes. The final scene, set to the pleasant guitars of Los Indios Tabajares, finds Zama’s bloody stumps wrapped, his half-dead body ferried through a lush, green swamp by two natives, as though carried by Charon through the river Styx. A boy on the boat asks him, “Do you want to live?” Throughout the film, Zama has waited, denied himself, and pretended, but he has never lived.

For all of its artistic and thematic intricacy, Zama is also an uncommonly beautiful film that revels in Nature’s sublimity. The director’s efforts have earned their comparisons to the renegade exquisiteness of Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) or Fitzcarraldo (1982)—productions that were shot in the Peruvian jungle and transmit the same horrible grandeur as Martel’s film. The director and Portuguese cinematographer Rui Poças, shooting on a budget of $3.5 million in entirely open-air locations throughout Formosa, Argentina, capture imagery that, in almost all cases, presents a divergence of setting and character. The opening shots on the beach contrast Zama’s melancholy presence with an idyllic oceanside view; scenes in the jungle balance the inherent dangers with captivating fauna; Zama’s final moments onscreen pair his mutilated, near-dead body with a gorgeous marsh of the most outstanding greens. Costumer Julio Suárez made authentic costumes that provide a visual accent to the landscape—in particular, Zama’s crimson red jacket. Further demarcating Zama’s onscreen presence are Cacho’s regal and aquiline features, which, given his character’s pitiful status outside of both the colonial bureaucracy and the colonized locals, represent the film’s most constant visual irony.

An exquisite and haunting adaptation of Antonio Di Benedetto novel, Lucrecia Martel’s Zama is sensuous and formally audacious—a tremendous synthesis of textual adaptation, directorial authorship, sociopolitical commentary, and sophisticated filmmaking. Her work ruminates on its intricate motifs, exploring them in effusive, hypnotic, and often mystifying ways. However contemptibly and pettily Don Diego de Zama may behave in Zama, the film’s absorption into his subjectivity offers some manner of sympathy given his functionary role in the system of colonialism. In this sense, Martel follows in the tradition of great critiques of colonialism in Latin American filmmaking, as it articulates why colonialism cannot work, as the colonized remains ever at odds with the colonizer, no matter the degree to which parties on both sides seek cultural entanglement. Zama’s position within that system is nothing more than that of a powerless symbol, inessential and, much like the natives, a casualty of colonial destruction, both physically and culturally. His life is painfully funny yet also an inescapable absurdist nightmare. Martel renders this not through bold statements or direct commentary; rather, through the uncertain spaces between time and identity, the diffusion of a fever dream.

Bibliography:

Allen, Esther. “The Crazed Euphoria of Lucrecia Martel’s ‘Zama’.” The New York Review of Books. 14 April 2008. nybooks.com/daily/2018/04/14/the-crazed-euphoria-of-lucrecia-martels-zama/. Accessed 10 November 2018.

Di Benedetto, Antonio. Zama. Translation and introduction by Esther Allen. The New York Review of Books, 2000.

Guest, Haden, and Phillip Penix-Tadsen. “Lucrecia Martel.” BOMB, no. 106, 2009, pp. 30–37.

Oubiña, David. “La Ciénaga: What’s Outside the Frame.” The Criterion Collection. 26 January 2015. criterion.com/current/posts/3444-la-ci-naga-what-s-outside-the-frame. Accessed 14 November 2018.

Taubin, Amy. “Identification of a Woman.” Film Comment, vol. 45, no. 4, 2009, pp. 20–23.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review