The Definitives

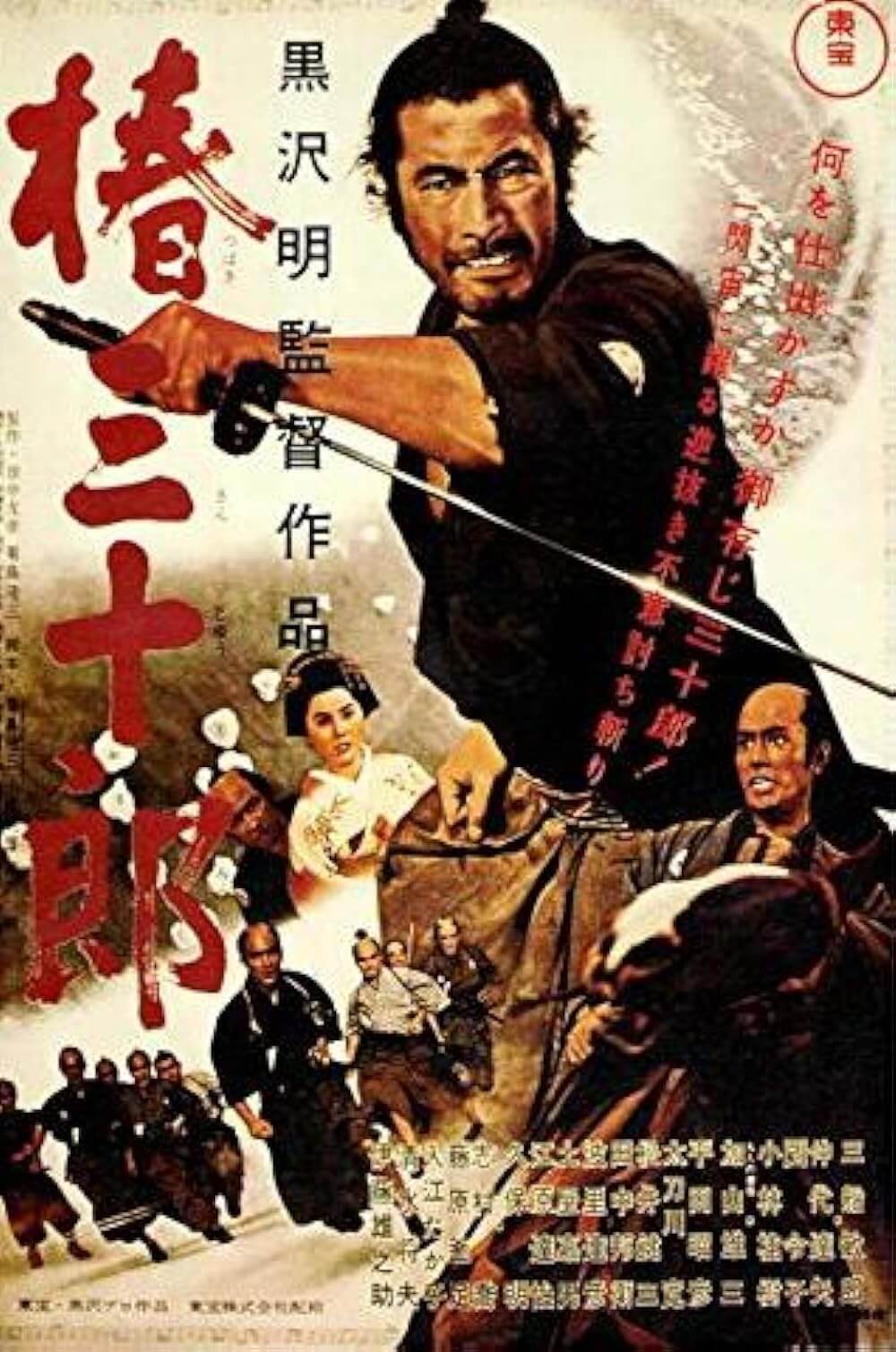

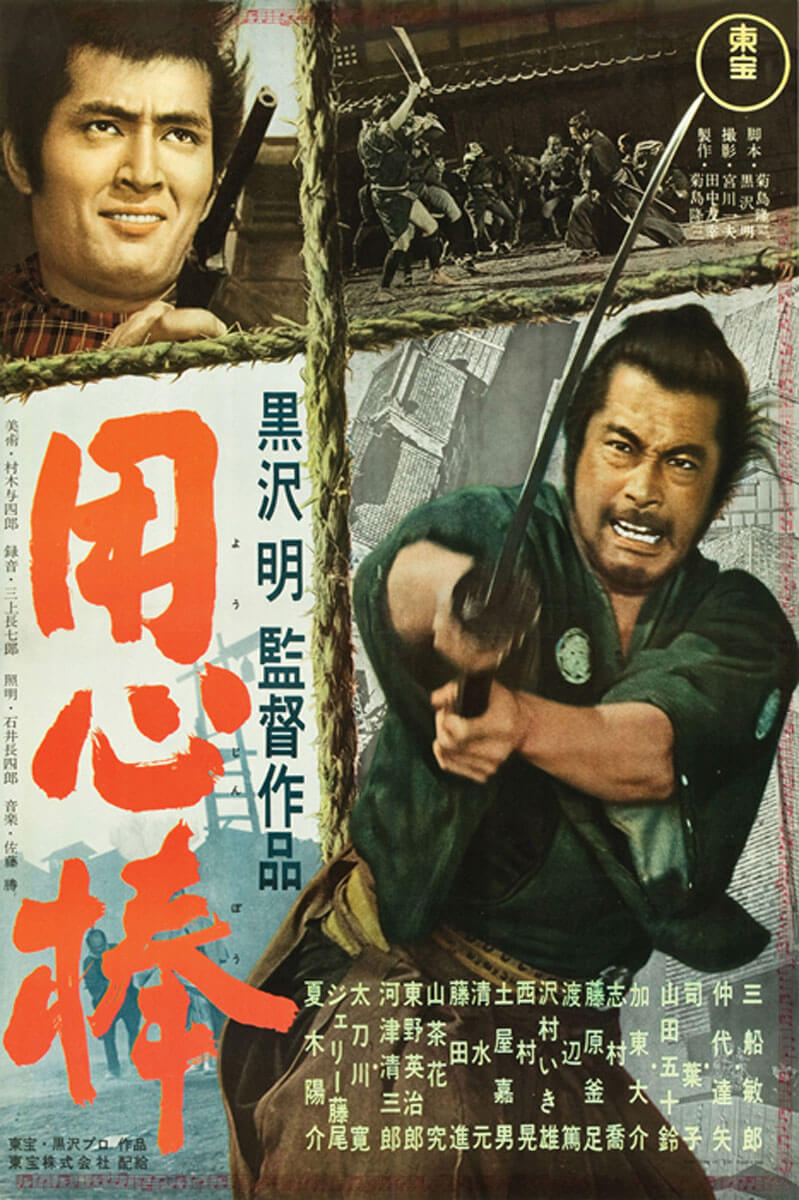

Yojimbo (1961)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo begins with a ronin, a masterless samurai who wanders here and there, making a living by his sword, at a literal crossroads. By chance, the unkempt samurai chooses a path to a small town. As he enters, a farmer argues with his son, an impetuous sort yearning for an “exciting life.” The ronin continues up the town’s desolate main street, faces in windows gawking at him. Up ahead, a dog prances his way with a severed human hand in its jaws. At first, the samurai looks surprised, but he continues nonetheless; he knows places like this teem with opportunities to make money. He quickly gathers that two rival gangs have taken control of the town, turning it into a wasteland of corruption and death. Scratching his stubbly chin, he resolves to stay and, much to his amusement, he watches as the two gangs destroy each other with little effort on his part.

Whether the samurai delivers punishment for seeking a more stimulating gangster life away from the farm, or merely does so to entertain himself, either explanation defies expectations held by Japanese audiences upon Yojimbo’s release in 1961. Everything about the film disassembles the chambara genre, a division of jidai-geki or Japanese period film, featuring prominent actionized sword fighting and usually samurai. He turns chambara upside down and inside out by incorporating influences from the Western genre, largely the films of John Ford, and mocking the harsh world depicted in chambara films before his reinvention. Just as Kurosawa used Seven Samurai to reimagine traditional views of the samurai, in Yojimbo he employs the swordplay genre to satirize the world’s indifference, senseless violence, and criminality. He avoids a typical good-versus-evil plot and submerges the viewer in a setting overridden by—with one or two exceptions—deplorable characters.

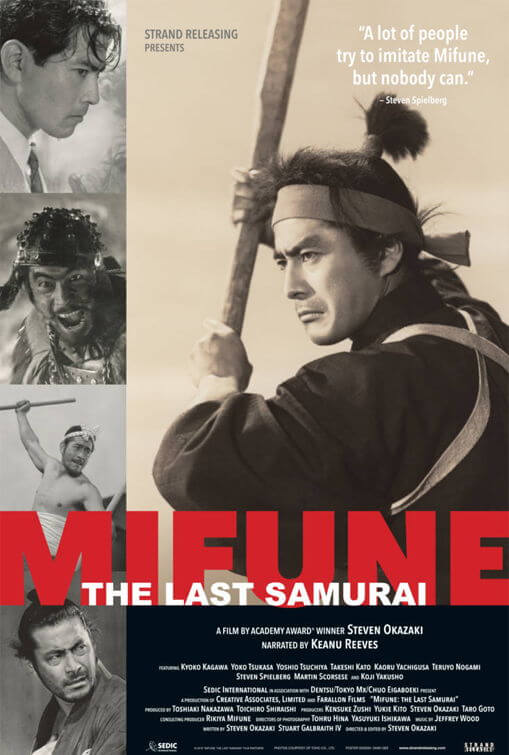

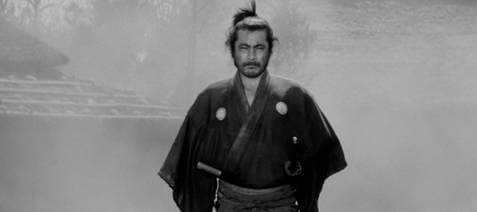

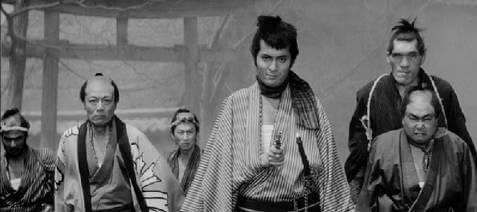

Enter the great Toshiro Mifune as the ronin named Sanjuro. Like the gods in Greek mythology, the character descends into a lowly town and pulls the strings on human puppets until they destroy each other. Their behavior does not concern him, though it may distract his attention for a brief moment or two, between a nap and dinner. Sanjuro’s presence sets the mortals into motion; as they act out their pithy drama, he stands by and watches, mildly entertained, equally amoral but far superior in his skill and intelligence. The town’s rival gangs are headed by a silk merchant, Tazaemon (Kamatari Fujiwara), and his henchman Seibei (Siezaburo Kawazu). Opposing him is the saké merchant, Tokuemon (Takashi Shimura), followed by henchman Ushitora (Kyu Sazanka). Both factions have employed a rogue’s gallery of goons-for-hire, each crew built for size over excellence. Only Ushitora’s younger brother, Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), presents any real danger when he returns to town with a pistol that makes him seemingly unstoppable. Sanjuro hires himself out to either side, commanding their dependence on him with his skilled swordsmanship, and manipulates both gangs to wipe each other out. In the end, everyone who purveyed violence is dead, leaving only a select few alive; just as in Seven Samurai, those who choose not to fight will endure. With that, Sanjuro turns to the few remaining townspeople and says “Abayo!” or “Bye!” without giving them a second thought.

Enter the great Toshiro Mifune as the ronin named Sanjuro. Like the gods in Greek mythology, the character descends into a lowly town and pulls the strings on human puppets until they destroy each other. Their behavior does not concern him, though it may distract his attention for a brief moment or two, between a nap and dinner. Sanjuro’s presence sets the mortals into motion; as they act out their pithy drama, he stands by and watches, mildly entertained, equally amoral but far superior in his skill and intelligence. The town’s rival gangs are headed by a silk merchant, Tazaemon (Kamatari Fujiwara), and his henchman Seibei (Siezaburo Kawazu). Opposing him is the saké merchant, Tokuemon (Takashi Shimura), followed by henchman Ushitora (Kyu Sazanka). Both factions have employed a rogue’s gallery of goons-for-hire, each crew built for size over excellence. Only Ushitora’s younger brother, Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), presents any real danger when he returns to town with a pistol that makes him seemingly unstoppable. Sanjuro hires himself out to either side, commanding their dependence on him with his skilled swordsmanship, and manipulates both gangs to wipe each other out. In the end, everyone who purveyed violence is dead, leaving only a select few alive; just as in Seven Samurai, those who choose not to fight will endure. With that, Sanjuro turns to the few remaining townspeople and says “Abayo!” or “Bye!” without giving them a second thought.

Often mistaken as an escapist samurai action film, Yojimbo, like most Kurosawa pictures, is not without a greater purpose, though comparatively “light” when placed next to Ikiru or The Bad Sleep Well. Through his rugged anti-hero, the director steps back to observe, with disdain, the cruelty of the world through his story’s oligopoly of yakuza gangsters. Point-of-view shots align our perspective with Sanjuro, who relaxes on a watchtower as the two gangs prepare for battle. Kurosawa asks that his audience, too, watches this mad, violent comedy from on high with indifference as countless men kill each other, by the end, leaving so many bodies in the streets not even the town’s greedy casket-maker bothers assembling coffins. Tough gangsters are depicted as sniveling cowards afraid to engage in battle, posturing and retreating from one another like schools of warring fish, as the director observes from Sanjuro’s angle the hilarity of their big talk and spineless behavior. Looking down at the allegorical town’s madness, all one can do is laugh at the absurd, self-destructive nature of humanity.

Steered by chance, or perhaps fate, Sanjuro seems to descend upon the town to restore order to what has become social anarchy. The boy who runs off to join a gang after quarreling with his father implies civil disorder has swept over the countryside. As the farmer’s wife remarks, “Everyone is after easy money these days.” Kurosawa’s comic actioner becomes a tale about the breakdown of society, with neighbors at war and greed soaking the streets with blood. Kurosawa searches for a rare glint of beauty and freedom, but finds it nowhere in this horrid little town, until Sanjuro witnesses a child desperate for his degraded mother. Along with her husband, a mere farmer, this family represents the single mark of decency in a town ruled by crime. Sanjuro saves them, although he would never let them, or the audience, know why. In the final scenes, after Sanjuro has killed the last of the town’s gangsters, he corners the young man who wanted an exciting life and tells him to go back to the farm. The boy gladly does. Kurosawa intended his message for young Japanese, his contempt of the yakuza prevalent throughout his oeuvre (and most apparent in Drunken Angel), but the anti-gang message reaches audiences even in today’s world.

Steered by chance, or perhaps fate, Sanjuro seems to descend upon the town to restore order to what has become social anarchy. The boy who runs off to join a gang after quarreling with his father implies civil disorder has swept over the countryside. As the farmer’s wife remarks, “Everyone is after easy money these days.” Kurosawa’s comic actioner becomes a tale about the breakdown of society, with neighbors at war and greed soaking the streets with blood. Kurosawa searches for a rare glint of beauty and freedom, but finds it nowhere in this horrid little town, until Sanjuro witnesses a child desperate for his degraded mother. Along with her husband, a mere farmer, this family represents the single mark of decency in a town ruled by crime. Sanjuro saves them, although he would never let them, or the audience, know why. In the final scenes, after Sanjuro has killed the last of the town’s gangsters, he corners the young man who wanted an exciting life and tells him to go back to the farm. The boy gladly does. Kurosawa intended his message for young Japanese, his contempt of the yakuza prevalent throughout his oeuvre (and most apparent in Drunken Angel), but the anti-gang message reaches audiences even in today’s world.

With Yojimbo full of crime and deplorable people, satiric humor sets Kurosawa’s tone—to the extent that this film is often called the director’s only full-length comedy. His comic intentions are most apparent in the heightened caricatures present in the film, many derived from Westerns and others almost Dickensian in their palpable framework, all grotesques, tattooed and animal-like. A flock of shabby geishas answer to Seibei’s wicked wife, Orin (Isuzu Yamada), who reigns over her weak husband. A hilariously seedy undertaker played by Atsushi Watanabe is pleased by the business the ronin brings to his village, the more coffins the merrier, recalling a dozen undertakers seen preparing caskets just before a showdown in a dozen Westerns. Or Nakadai’s maniacal villain, so fascinated by his deadly new gizmo that kills with so little effort; his bloodthirsty madness flashes a wild-eyed grin across the actor’s face. Every henchman looks brutish, such as the gargantuan strongman who is paired with a petite cohort, or oafish Ushitora, whose name (which in part means “boar”) reflects his boar-like appearance. Villainous, ever-devious gang bosses behave with pathetic uncertainty when confronted. All the while, Kurosawa revels in the deplorable nature of the townspeople, and such cartoonish characterizations remind us of his objective to make Yojimbo a comedy, almost an attack on reckless chambara films popular in the period.

To be sure, of Yojimbo’s countless imitations and actionized remakes, all subsequent copycats fail to achieve Kurosawa’s entrenched comedic satire. The greatest caricature remains Mifune’s Sanjuro, a performance that defies everything heroic and honorable about the actor’s samurai portrayal in Hiroshi Inagaki’s Musashi Miyamoto trilogy in the previous decade, but no less iconic. Mifune, improvising shrugs and scratching his unshaven face or the back of his head, displays the mannerisms of a scruffy loner with no money and garbed in a filthy kimono, but also a character of respectable intentions despite outward appearances. Mifune’s casual and contemplative reactions to a large opponent or an unexpected severed limb are hilarious, slyly comic expressions, whereas his sardonic silence requires just as much indefinable presence. Between two gangs of embellished criminality, the audience has no choice but to sit on the sidelines with Sanjuro, who may be the greatest killer in the film, until both parties have torn each other apart, leaving Sanjuro the hero for orchestrating a town cleanup and helping an innocent family escape. The anti-hero persona created by Kurosawa and Mifune—his confident saunter, arms warmed within his kimono, toothpick in mouth—spread no end of influence throughout cinema.

To be sure, of Yojimbo’s countless imitations and actionized remakes, all subsequent copycats fail to achieve Kurosawa’s entrenched comedic satire. The greatest caricature remains Mifune’s Sanjuro, a performance that defies everything heroic and honorable about the actor’s samurai portrayal in Hiroshi Inagaki’s Musashi Miyamoto trilogy in the previous decade, but no less iconic. Mifune, improvising shrugs and scratching his unshaven face or the back of his head, displays the mannerisms of a scruffy loner with no money and garbed in a filthy kimono, but also a character of respectable intentions despite outward appearances. Mifune’s casual and contemplative reactions to a large opponent or an unexpected severed limb are hilarious, slyly comic expressions, whereas his sardonic silence requires just as much indefinable presence. Between two gangs of embellished criminality, the audience has no choice but to sit on the sidelines with Sanjuro, who may be the greatest killer in the film, until both parties have torn each other apart, leaving Sanjuro the hero for orchestrating a town cleanup and helping an innocent family escape. The anti-hero persona created by Kurosawa and Mifune—his confident saunter, arms warmed within his kimono, toothpick in mouth—spread no end of influence throughout cinema.

However iconic and authoritative, Kurosawa and Mifune instill Sanjuro with guarded humanity, as cracks in the samurai’s contemplative, selfish, manipulative, god-like performance reveal occasional moments of compassion. Sanjuro’s inflated perspective dominates the majority of the film: we see gangsters as duplicitous and grotesque because that is how Sanjuro sees them; the “conflict” of the film rests with the almighty Sanjuro keeping himself busy, finding something to eat and something to taper his boredom while wholly removed from the town’s pitiable goings-on. But his godly stature is brought down to earth when the child’s family shows gratitude for being saved and bows to their savior. “Shut up! I hate grateful people,” he shouts. “If you cry, I’m going to kill you right now!” Their gratitude forces Sanjuro to acknowledge his humanity, a quality of decency to which he refuses to deem himself capable. Sure enough, Kurosawa punishes the character for his generosity when Unosuke finds the family’s ‘thank you’ note to Sanjuro and has him detained and beaten. After exposing his human weakness, Sanjuro, who escapes his capture to recover in a shed, becomes a more complex character, one who despises the wicked world and holds himself back from it. As his lesson shows, becoming involved is anything but desirable.

But when the world, more specifically Unosuke, confronts him, Sanjuro lashes back in violence. Unosuke and his gang have wiped out any opposing forces, the townspeople all but vanished. They string up the restaurant owner, who has provided Sanjuro with food and shelter, as bait. Obliging their lure, and in keeping with his god-like stature, Sanjuro marches into town and, without breaking his stride, slices through gang members in an impressive display of swordsmanship and agility. The final duel with gunslinger Unosuke leaves the thug whimpering and afraid, dying in a gathering pool of blood. With this, Kurosawa’s technical mastery brings another dimension to challenge the soundless and bloodless action in chambara films prior to Yojimbo. Earlier chambara films were known for their clanging swords; but when a blow was struck, only silence and no blood. Kurosawa adds a sense of consequence to the action by including fleshy sound effects and bloody outcomes.

But when the world, more specifically Unosuke, confronts him, Sanjuro lashes back in violence. Unosuke and his gang have wiped out any opposing forces, the townspeople all but vanished. They string up the restaurant owner, who has provided Sanjuro with food and shelter, as bait. Obliging their lure, and in keeping with his god-like stature, Sanjuro marches into town and, without breaking his stride, slices through gang members in an impressive display of swordsmanship and agility. The final duel with gunslinger Unosuke leaves the thug whimpering and afraid, dying in a gathering pool of blood. With this, Kurosawa’s technical mastery brings another dimension to challenge the soundless and bloodless action in chambara films prior to Yojimbo. Earlier chambara films were known for their clanging swords; but when a blow was struck, only silence and no blood. Kurosawa adds a sense of consequence to the action by including fleshy sound effects and bloody outcomes.

Death’s visual and aural reality in Yojimbo set the picture apart from standard chambara films of the era, which rarely used blood or flesh-chopping sounds to convey the physical veracity of a blow from a samurai sword. In a conversation with sound mixer Ichiro Minawa, the director determined there should be a sound effect for a sword cutting into a body; Minawa went to a butcher and bought several cuts of meat, chopping them with a sword and recording the outcome (the crew ate the hastily chopped results). The sounds were far too quiet until Minawa tried a chicken stuffed with wooden chopsticks for a bony effect. The technique would become an industry standard in Japan. As for blood, Kurosawa insisted the stuff spurt onto walls behind Sanjuro’s enemies as they were cut down and pools form under their bodies. The graphic images shocked audiences around the world and predated violent pictures like Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Wild Bunch (1969) frequently cited as the origin of modern violence in cinema.

But rather than add a sense of bloody theatricality, the effect heightens the picture’s realism, insomuch that yakuza gangsters rarely confront each other onscreen, their earthly violence unrealized—Unosuke’s pistol kills mark the only exceptions. Like children or childlike mortals, they play act until Sanjuro, in all his superiority, reminds them that life is no game. And yet, composer Masaru Sato’s drumming score, one of the film’s most memorable attributes, associates Yojimbo with a performance piece, not unlike a stage piece being acted out, perhaps even a violent ballet. Even Mifune’s signature strut seems to align with Sato’s music in an effortless synchronization and tension-building momentum. Along with the meticulously detailed sets, Kurosawa’s dramatic staging, and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa balanced but asymmetrical framing, the film contains an opposing interplay between reality and cinematic fantasy that forces the viewer to consider how the latter enhances the former.

But rather than add a sense of bloody theatricality, the effect heightens the picture’s realism, insomuch that yakuza gangsters rarely confront each other onscreen, their earthly violence unrealized—Unosuke’s pistol kills mark the only exceptions. Like children or childlike mortals, they play act until Sanjuro, in all his superiority, reminds them that life is no game. And yet, composer Masaru Sato’s drumming score, one of the film’s most memorable attributes, associates Yojimbo with a performance piece, not unlike a stage piece being acted out, perhaps even a violent ballet. Even Mifune’s signature strut seems to align with Sato’s music in an effortless synchronization and tension-building momentum. Along with the meticulously detailed sets, Kurosawa’s dramatic staging, and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa balanced but asymmetrical framing, the film contains an opposing interplay between reality and cinematic fantasy that forces the viewer to consider how the latter enhances the former.

Though said to be vaguely inspired by Dashiell Hammett’s book Red Harvest, Kurosawa’s film begat several direct influences of its own, some credited and others not. After Italian director Sergio Leone saw Yojimbo in 1963, he announced to his wife that he would turn it into a Western. A month later he had written A Fistful of Dollars, the first in Leone’s increasingly grandiose “Spaghetti Western” series, unofficially called “The Man with No Name Trilogy”. Leone’s producers attempted to secure permission to adapt Kurosawa’s film but never followed through, apparently hoping no one would notice that the film was merely a light resurfacing of Yojimbo’s template. Shamelessly, Leone would later claim ignorance when no screen credit was given to Kurosawa, while his producers attempted to cover up their blunder with ridiculous legal jargon. But the lawsuit eventually filed by Toho and Kurosawa Production Co. would prove victorious. In an out-of-court settlement, Kurosawa received 15 percent of the worldwide receipts for Leone’s film, whose release was delayed until 1967 in the U.S. because of the legal troubles. When it finally premiered, Kurosawa was still not given credit. In 1992, New Line Cinema purchased the rights to remake Yojimbo as a 1930s-style shoot-em-up gangster picture, called Last Man Standing, the excessively violent and humorless result more akin to Red Harvest than its director Walter Hill or star Bruce Willis were willing to admit.

Kurosawa’s own influences are less direct and conceived from his affection for Western cinema, both in terms of geographical West and the Western genre, combined with his embrace and reinvention of Japanese history. Certainly, Kurosawa popularized, perhaps even gave birth to the international East-meets-West amalgamation of cinematic techniques and execution, calling for worldwide recognition of his artistry and accessibility beyond borders (his picture Rashomon drew enough attention to help inspire the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to establish the Best Foreign Film category in 1952). In Yojimbo, the East-meets-West theme becomes most evident through the marriage of chambara and cowboy archetypes. The symbolic final showdown between the rugged samurai and the modern gunslinger—counterparts for Japan and the United States, one armed with a classical sword and the other a modern weapon—suggest the convergence of cinematic styles present in the film, while also delineating their obvious differences. Through his modernized villain so much more “advanced” and powerful than the hero, Kurosawa makes Sanjuro’s inevitable victory all the more impressive, while slyly hinting at the sometimes dangerous influence of American culture, which played such a detrimental role in developing Japan’s postwar yakuza image.

Kurosawa’s own influences are less direct and conceived from his affection for Western cinema, both in terms of geographical West and the Western genre, combined with his embrace and reinvention of Japanese history. Certainly, Kurosawa popularized, perhaps even gave birth to the international East-meets-West amalgamation of cinematic techniques and execution, calling for worldwide recognition of his artistry and accessibility beyond borders (his picture Rashomon drew enough attention to help inspire the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to establish the Best Foreign Film category in 1952). In Yojimbo, the East-meets-West theme becomes most evident through the marriage of chambara and cowboy archetypes. The symbolic final showdown between the rugged samurai and the modern gunslinger—counterparts for Japan and the United States, one armed with a classical sword and the other a modern weapon—suggest the convergence of cinematic styles present in the film, while also delineating their obvious differences. Through his modernized villain so much more “advanced” and powerful than the hero, Kurosawa makes Sanjuro’s inevitable victory all the more impressive, while slyly hinting at the sometimes dangerous influence of American culture, which played such a detrimental role in developing Japan’s postwar yakuza image.

Drawn from Hollywood’s long history in the Western genre, as well as his own personal affection for the films of John Ford (My Darling Clementine, The Searchers), Kurosawa’s setting embodies archetypal Western traits, his lone swordsman moseying into the frightened town like Gary Cooper in High Noon, cautious but prepared for anything. Many of the characters fit typical Western tropes (the aforementioned casket-maker, geishas as saloon whores, a knowing bartender, etc.), while the dusty, windswept settlement itself was modeled after countless failed boom towns from Westerns. Eight wind machines were used to create gusts that blow dead leaves and dirt through the streets, causing no end of debris in the air—and Kurosawa would not allow his actors to blink onscreen despite the effect; they were forced to wash out their eyes between takes. But to call Yojimbo derivative based on its few similarities to the American Western would be an oversimplification; instead, call it inspired post-modernism.

Redefining not only a Japanese genre but a Hollywood one, Kurosawa’s Yojimbo testifies to the cyclical, international pathways of inspiration driving cinematic art. But more than its inward and outward flowing influences, or even its prevalent, satiric commentaries on social order crumbling under growing corruption and yakuza brand criminality, the film deepens its foundational themes and elevates diversionary filmmaking into something intertextual. Through impressive bursts of action and one of the most iconic central performances in screen history, Kurosawa hides his artistry behind his most entertaining picture, seamlessly combining inventive methods with mainstream appeal. Achieving a rarely found ideal in which art and accessibility are merged, Yojimbo remains one of the great cinematic entertainments—a film deceptive enough in its simplicity to leave audiences is unaware that what they have just witnessed is a crafty, intelligent picture disguised as an escapist samurai film.

Redefining not only a Japanese genre but a Hollywood one, Kurosawa’s Yojimbo testifies to the cyclical, international pathways of inspiration driving cinematic art. But more than its inward and outward flowing influences, or even its prevalent, satiric commentaries on social order crumbling under growing corruption and yakuza brand criminality, the film deepens its foundational themes and elevates diversionary filmmaking into something intertextual. Through impressive bursts of action and one of the most iconic central performances in screen history, Kurosawa hides his artistry behind his most entertaining picture, seamlessly combining inventive methods with mainstream appeal. Achieving a rarely found ideal in which art and accessibility are merged, Yojimbo remains one of the great cinematic entertainments—a film deceptive enough in its simplicity to leave audiences is unaware that what they have just witnessed is a crafty, intelligent picture disguised as an escapist samurai film.

Bibliography:

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber, 2002.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like An Autobiography. New York: Knopf: distributed by Random House, 1982.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

(NOTE: This essay was updated on March 24, 2023, to correct a reference to the gods of Greek mythology.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review