The Definitives

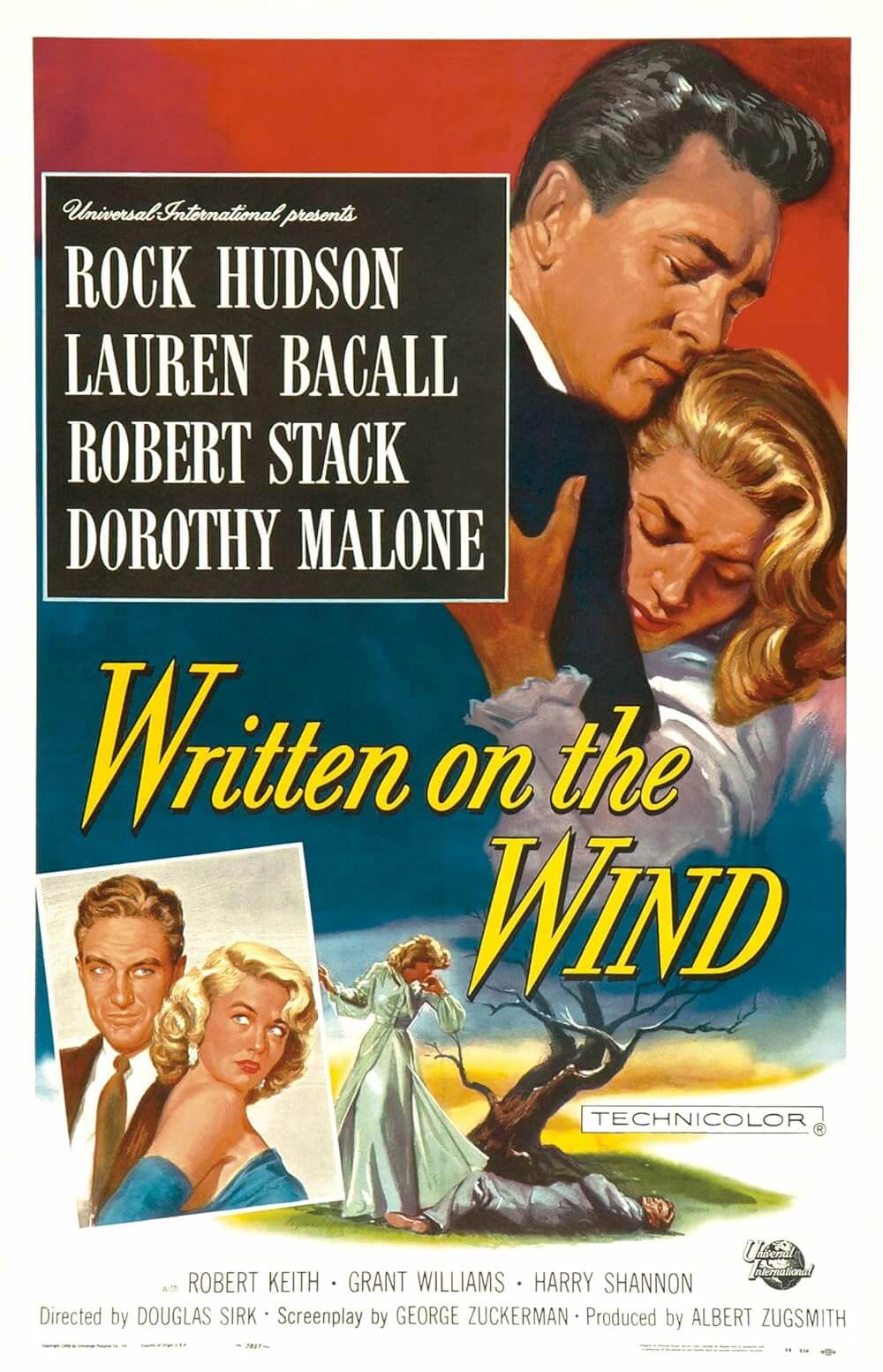

Written on the Wind

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Melodrama should not be taken lightly or dismissed as trash, at least not when it applies to Douglas Sirk’s variety, and certainly not when considering Sirk’s wild and frothy Written on the Wind. His film is an exercise in style; he creates an archetypal genre yarn and enhances it by furnishing the subtext with metaphoric symbols like mirrors and flowers, figurative uses of color, and unrelenting irony. Concealing his satirical edge with all the trickery offered by a Hollywood studio, namely Universal Studios, Sirk made popular and vital art under the noses of his producers, who were just happy the director’s films performed at the box office. But most of all, Sirk fashioned an immaculate balance between his own personal style and the subject matter of his films.

Sirk, along with Ernst Lubitsch, Otto Preminger, Robert Siodmak, and Billy Wilder, was among scores in the film community to anticipate Hitler’s burgeoning power and escape Nazi-influenced Europe in the 1930s. He feared an environment where familiar faces suddenly turned to Nazism, and as a theater director, he was swiftly prevented from doing the avant-garde pieces he was known for. And so he fled, seeing no other choice financially than to break into filmmaking, the more lucrative directorial medium in America. Europe, meanwhile, was losing its best artists; Goebbels even sent Sirk a letter pleading for his return to Germany, suggesting the director’s Jewish wife could remain outside the country and receive money. Sirk made it to Holland and caught the last boat to America. After landing in New York, Sirk later arrived in Hollywood in 1939 and settled inside a community of European exiles that had migrated to the West Coast. He directed pictures for Columbia and United Artists throughout the 1940s, among them Hitler’s Madmen of 1943, and based on the popularity of A Scandal in Paris from 1946, Sirk became a house director for Universal Studios in the 1950s, assigned to mostly forgettable light comedies and crime thrillers. Not until his first foray into melodrama would Sirk find the career-defining genre and stylistic freedom he once enjoyed in Germany.

Released artistically by the commercial success of Magnificent Obsession in 1954, Sirk’s interest in melodrama was not fuelled by a devoted interest in the genre’s stories; rather quite the opposite. The freedom of melodrama for Sirk, an artist otherwise suspcious of straightforward and one-dimensional narratives, resides in the potential for the duplicitous meaning he imbues onto every plot twist, every synthetic setpiece, every line of dialogue bubbling with parody yet unreserved gravity. As a result, Sirk’s inventory of melodramas with Universal represents an incomparable collection of films writhing with undertonal importance, but also constituting a model for future explorations of the genre (such as television’s Dallas or any relative fare barely hanging on to the face value of Sirk’s structure). However, today’s melodrama lacks Sirk’s sardonic yet urbane approach, because though his name is synonymous with the genre, he remained ever critical of it.

Released artistically by the commercial success of Magnificent Obsession in 1954, Sirk’s interest in melodrama was not fuelled by a devoted interest in the genre’s stories; rather quite the opposite. The freedom of melodrama for Sirk, an artist otherwise suspcious of straightforward and one-dimensional narratives, resides in the potential for the duplicitous meaning he imbues onto every plot twist, every synthetic setpiece, every line of dialogue bubbling with parody yet unreserved gravity. As a result, Sirk’s inventory of melodramas with Universal represents an incomparable collection of films writhing with undertonal importance, but also constituting a model for future explorations of the genre (such as television’s Dallas or any relative fare barely hanging on to the face value of Sirk’s structure). However, today’s melodrama lacks Sirk’s sardonic yet urbane approach, because though his name is synonymous with the genre, he remained ever critical of it.

Melodrama literally means a combination of melody and drama, which suggests a bold if emblematical way of storytelling. Surely this does not suggest melodramas are musicals, rather today’s definition is fairly conceptual in its explanation. Of course, music plays a significant role in creating the lofty dramatic points in such a story, allowing the audience to become involved because of the score’s elucidation of an emotional moment. But beyond that, melodrama is defined by lucid and emphatic narrative structure, complete with heavy rises and deeply affecting falls. From its origins in medieval morality plays to its breakthrough in French opera, the melodrama has evolved and been oversimplified throughout the centuries, and now is somehow cheap and unrefined in its soap opera classification. Music still constitutes a key device in melodrama, since it denotes the storyline’s rollercoaster configuration, which in turn comprises the details of the narrative. Melodrama inhabits stories about class struggles, conflicts between the upper and lower social ranks, frequently taking sympathy with the underdog for greater emotional impact. Much of the genre’s connotation relies on a severe and even blatant weight of conflicts, so that every confrontation and every staged clash is described with potent vitality, and punctuated by the striking music score. Actions are unambiguous, subtlety is almost nonexistent, and the expressive intrigue of the plot is communicated with explicit articulation.

Sirk believed melodrama was inherent to Hollywood cinema, and so his investigation of the genre was natural for him not only in his method of defining it for future filmmakers, but in the way he saw himself as a parodist at once outlining the genre’s tropes and satirizing them within the mise en scène. He called the genre a “drama of psychic violence,” and thus painted such behavior in aggressive colors, employing color symbolism to elucidate his social critiques. Indeed, Sirk was wholly aware of every detail in his films, tying implication onto the filmic environment and the story structure with a tight, gaudy ribbon. From 1954 to 1959, Sirk’s series of melodramas defined the field throughout his brief-but-crucial exploration of the genre. Describing them as “metaphysical,” these pictures often included the suffering or death of one character so that another could live, a theme that underscored each narrative to varying extremes.

His sudsy breakout into melodrama, Magnificent Obsession, features a reckless well-to-do saved by resuscitator after a boating accident, while at that instant a selfless doctor dies in need; the surviving pleasure-seeker reforms to make amends and eventually falls in love with the doctor’s widow, and then becomes a doctor himself. All That Heaven Allows (1955) centers on a widowed suburban woman enclosed by social boundaries, who scandalously falls for her gardener and learns life and love are about appeasing yourself, not your community sewing circle. Based on William Faulkner’s “unfilmable” novel, The Tarnished Angels (1958) features a daredevil pilot risking his family and life for nothing, until someone close to him teaches him a fatal lesson about appreciation. And in Sirk’s last Hollywood film, the racially charged Imitation of Life (1959), a light-skinned African American girl takes shame in her race and attempts to pass herself as white, until her mother dies and she develops pride in her race.

Written on the Wind arrived in 1956, colliding onto the screen as Sirk’s most confident and playful title. Robert Wilder wrote the novel in 1945, and George Zuckerman brought it to life within his screenplay—a spectacular tale about the spoiled and venomous brood of fictional oil magnate Jasper Hadley. Enough film scholars have analyzed the narrative in detail to make new, extensive examination into every plot point redundant. And so, why place surplus importance onto the events of the film when Sirk hardly cared about the scenarios himself? Because his picture is a sumptuous yet outrageous joy wrought with unforgettable behavior, tempting romance, and raw performances. He purveys sensationalist drama and harsh criticisms of upper classes, implemented with submissive artistry lingering under the surface like an expressionist engine, activated by the audience’s participation in and observation of his production.

Drunken playboy Kyle Hadley (Robert Stack) and his promiscuous sister Marylee (Dorothy Malone, in her Oscar-winning performance) live in their father’s mansion, in Hadleyville no less. Both subsist in the shadow of family friend Mitch Wayne (Rock Hudson), their father’s right-hand man who was all but adopted by the Hadleys in adolescence. Kyle could never keep it together like his pseudo-brother, while Marylee’s hopeless infatuation with Mitch grows increasingly desperate as time goes on. During one of Kyle’s spontaneous adventures, he and Mitch meet straightlaced working dame Lucy (Lauren Bacall), who Kyle quickly introduces himself by asking, “How would you like to join the Kyle Hadley society for the prevention of boredom?” Her common sense and aversion to chaos would make Lucy ideal for the levelheaded Mitch, but the film would avoid all drama and unfold rather plainly with that logical coupling. Instead, Lucy and Kyle end up married within a day, she confusing pity with love for his veiled undercoat of tragic self-destructiveness. Mitch continues in agony, tortured by his love for Lucy and his knowing that Kyle can never make her truly happy. And Marylee, she makes fruitless advances on Mitch with all the subtlety of an atomic bomb.

The Hadley family children are either sexually inadequate or disturbed in some way, and the virtual faultlessness and composure of Mitch and Lucy drive them crazy. Furthermore, they refuse to acknowledge their own flaws, and any blows to their egos result in a catastrophic backlash. Kyle and Lucy’s marriage proceeds without incident for a year; he even stops drinking, until his doctor explains why they cannot have children. “There’s nothing wrong with Lucy,” the doctor clarifies. Kyle just has “a weakness” the doctor assures can be bettered, which Kyle translates as utter failure as a husband, and more basically as a man. The boozehound carousel starts again. Of course, in Hadleyville, a Freudian dreamscape with phallic symbols everywhere—pumpjacks rising up and down, derricks raised into the sky—Kyle is bound to be sensitive about his potential sterility, and thus feel like a disappointment to his father who erected such rigs.

The Hadley family children are either sexually inadequate or disturbed in some way, and the virtual faultlessness and composure of Mitch and Lucy drive them crazy. Furthermore, they refuse to acknowledge their own flaws, and any blows to their egos result in a catastrophic backlash. Kyle and Lucy’s marriage proceeds without incident for a year; he even stops drinking, until his doctor explains why they cannot have children. “There’s nothing wrong with Lucy,” the doctor clarifies. Kyle just has “a weakness” the doctor assures can be bettered, which Kyle translates as utter failure as a husband, and more basically as a man. The boozehound carousel starts again. Of course, in Hadleyville, a Freudian dreamscape with phallic symbols everywhere—pumpjacks rising up and down, derricks raised into the sky—Kyle is bound to be sensitive about his potential sterility, and thus feel like a disappointment to his father who erected such rigs.

Marylee, meanwhile, remains driven by insatiable sexuality. Though she throws herself at Mitch, she also picks up local men. When police bring her home one evening accompanied by her John, the young man tells Jasper of her unchaste night life, confessing, “You’re daughter’s a tramp, mister!” Jasper instinctively reaches for a pistol, but Mitch stops him. Consumed by disappointment, the industrialist makes his way upstairs. Sirk cuts back and forth between Marylee and Jasper. She moves to a jazzy jungle dance in her room, holding Mitch Wayne’s picture, smoking, gyrating her loose hips about, and undressing into a red nightgown. All at once, Jasper tumbles down the stairs. Marylee’s easy virtue kills her father. Watch Malone in her role. She writhes like a drug addict hungry for more; her portrayal is brilliantly brazen. Using Kyle’s weakness to her advantage, Marylee tells him of Lucy’s unexpected pregnancy, suggesting Mitch is the father. Mitch is too honorable for an affair, however; Kyle is the father, though his certainty in his emasculation will not let him believe this. Staggering through the front door with a wave of dead leaves following him inside, he confronts his friend Mitch in a stupor with his father’s gun, and in the struggle, Kyle dies. Mitch and Lucy can pursue their probable love. And Marylee is left the man of the house. Malone miraculously creates a monster of sympathy at the end of the film when she appears at Jasper’s desk, stroking the symbol of her father: his golden model of an oil derrick.

Directed on two levels, feral according to Stack and Malone, staid according to Hudson and Bacall, Sirk uses various manipulations of color to enhance the characters’ personas. Employing gorgeous Technicolor, cinematographer Russell Metty, who shot pictures ranging from Bringing Up Baby (1939) to Spartacus (1960), photographed Sirk’s melodramas, ingraining them with rich hues that reflected the moods and dramatic placement of the characters within the frame. Designing the expert lighting together, Metty’s partnership with Sirk also informed Bill Thomas’ costumes that identified the characters without an ounce of nuance. Mitch and Lucy’s wardrobes consist of modest browns, recessive greens, and unassuming grays. Kyle owns a coward-yellow sports car, but in his clothing attempts business professional as compensation. Marylee’s garb is primarily vaginal-colored, with low-cut pink and red dresses, or a plaid shirt of electric pink and blue. She drives a fire-red vehicle, and her room is decorated with labia-shaped flowers. Only in her last scenes, when she finally must take over her father’s position, does she appear in a gray business suit.

Sirk makes such illustrative color choices apparent to signify the fundamental deception inborn to Hollywood cinema and melodrama as an artform, which in turn identify the social elitism of the Hadleys as equally illusory. The sets and backdrops are constructed with the finest matte paintings and production design, shot on Universal’s best studio lots, but Sirk intentionally avoids realism. He employs deliberate plasticity so the viewer sees past the gloss of his production to examine the artifice. Material details are collected to be noticed. The Hadley manor, for example, comes festooned with flowers, objects, space and things, and yet feels cold and empty, lonely and isolating. Mirrors on almost every wall point out the delusion of their façade, the reflectivity of the Hadleys’ false glory.

Written off as base, Sirk’s films were initially ignored by critics, even condemned as dramatic sensationalism. But as the title of his last melodrama indicates, Sirk’s films are an “imitation of life”—the perfect qualifier for his oeuvre. Later film scholars and historians from Laura Mulvey to Thomas Elsaesser rediscovered Sirk’s body of work, praising his marriage of distinctive visuals with subversive social commentary. Filmmakers like Pedro Almodovar, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Todd Haynes, Martin Scorsese, and François Truffaut would also sing his praises by way of written testimonials and cinematic tributes within their own works. And of course, soapy daytime dramas obtained their roots from Sirk’s variety of plot. Dripping with irony, Written on the Wind is more than Douglas Sirk’s assessment of an impotent class of moneyed folk. Viewers considering only the plot may indeed reduce the film to a collection of melodrama’s most conventional stereotypes. But viewers peering into the production’s mode of description, Sirk’s simultaneous appreciation and parody of his narrative, and the complication of the auteur’s mise en scène, will find something singularly enjoyable on the most primal, yet artistically sophisticated levels. Romance and intrigue are what draw the audience; Sirk’s elegant craftsmanship absolves them of their reservations.

Bibliography:

Camper, Fred. “The Films of Douglas Sirk.” Screen, Summer ’71, Vol. 12 Issue 2, p44-62.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama.” Film Genre Reader II, edited by Barry Keith Grant. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995, pp: 50-80.

Fassbinder, Rainer Werner. “Six Films by Douglas Sirk”, in Laura Mulvey & Jon Halliday, Eds. Douglas Sirk. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Film Festival ’72, 1972), p. 102.

Halliday, Jon. Sirk on Sirk. London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1997.

Klinger, Barbara. Melodrama and Meaning: History, Culture, and the Films of Douglas Sirk. Illustrated Edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review