The Definitives

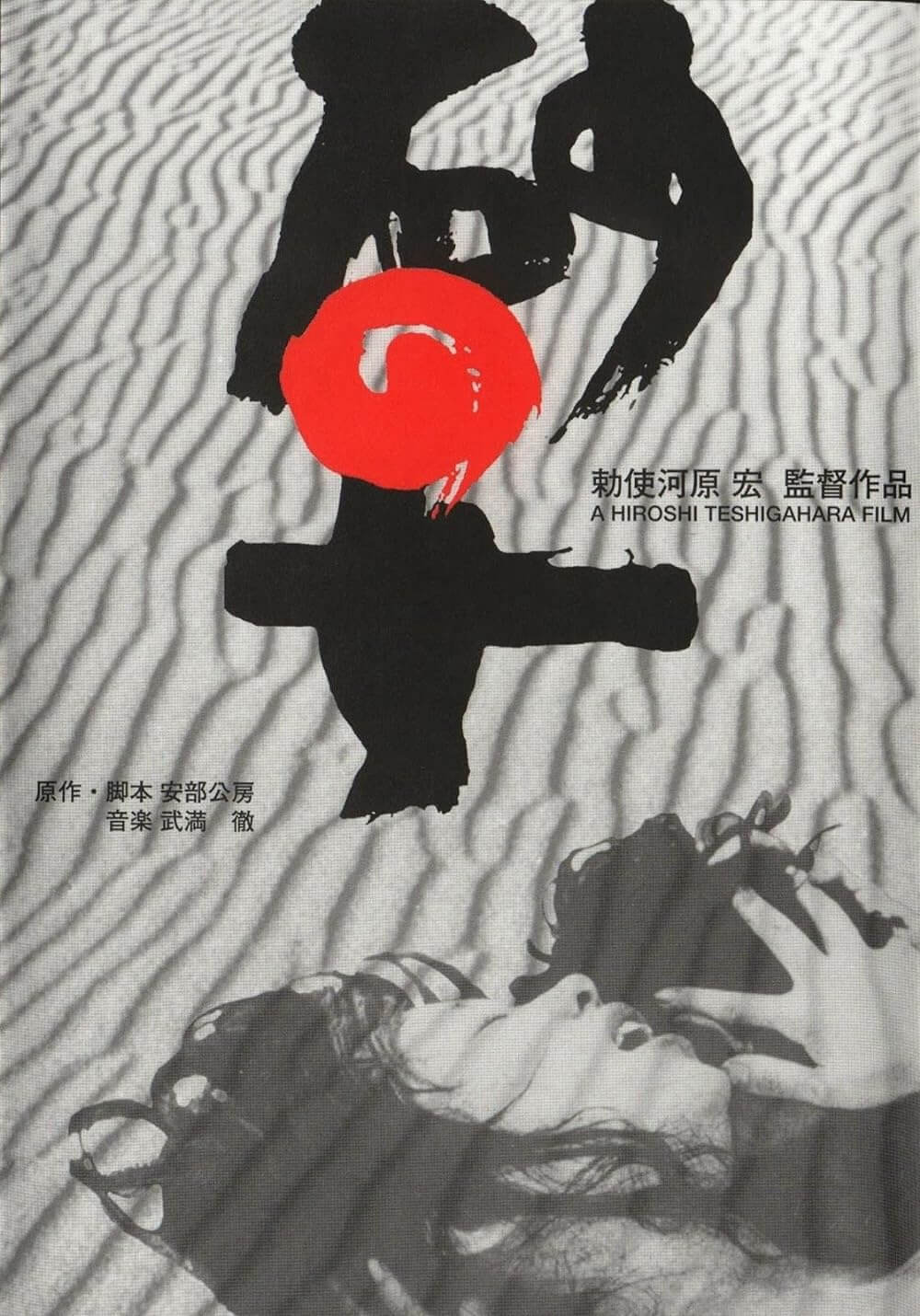

Woman in the Dunes (1964)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

A crystalline object fills the screen, surrounded by blackness and the mere impression of similar shapes around it. Reverberating layered strings carry a persistent banshee cry under the image, the shrill immediately haunting. The shape might be a honeycomb cell, except the light changes to illuminate what now becomes a central geological formation. Blown up to a hundred or more times actual size, this single grain of sand looks like some otherworldly thing, and the music fuels our suspicions. Then the shot cuts back to reveal dozens of others, that sharp gem of the first image having disappeared into the throng. Another cut outward and we see thousands now, multiplying like self-generating insect eggs inside a nest. A thunderous sound forms under the high-pitched strings, as another shift backward shows pebbles pushed by wind along patterns of sandy waves on the dune’s surface. A final cut shows us the face of a sandbank, and a lone wanderer treading uphill, oblivious to the seemingly anonymous grains looming around him on all sides. With these images the dunes have an identity; it’s a terrifying one, and we should be wary for this traveler.

The surreal, hyper-detailed landscape of Japanese New Wave filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes forms an allegorical setting of remarkable beauty and horrifying implication. Based on Kobo Abe’s best-selling novel, published in 1962, the film arrived only two years later, marking the second collaboration between director Teshigahara, writer Kobo Abe, and composer Toru Takemitsu, a trio of immeasurable artistic influence in postwar Japan. These collaborators plunge their audience into surroundings made suspect by the intense scrutiny put upon them, and in turn, the environment immerses the audience in this desert world and its larger connotations. A patter of sand creeps down a hillside; an insect disappears into the granules like a monster in the mist; music hisses behind this imagery; sand clinging to a naked body beckons to be wiped away. And it’s all indescribably unsettling and intensely sensual. Amid beguiling visual and aural descriptions, the filmmakers construct a deeply symbolic, enigmatic, even Kafkaesque scenario about the search for identity.

On a three day vacation to find rare sand beetles in a desert region of Japan, a schoolteacher and recreational entomologist (Eiji Okada) misses the last bus back to civilization. A group of villagers offers to put him up for the night with a local widow. He agrees, and they head to the widow’s home, a modest shack located at the bottom of a sandpit. Climbing a rope ladder to get down, he’s greeted by the widow (Kyoko Kishida), who lives alone and eagerly takes his things and prepares him dinner. As he dines, the schoolteacher disregards the widow’s vague comments about the length of his stay being more than just overnight, just as he overlooks the villagers dropping tools into the pit for the woman’s “helper”. At night, she digs sand from the ground into wooden baskets, which are then lifted by the villagers above by a rope and pulley system. The schoolteacher watches and asks if he can help. “Not on the first day,” she replies. He tries again to explain he’s only staying for the night but assumes the misunderstanding is inconsequential. He goes off to bed after she explains her work must continue through the night because “the sand won’t wait.”

On a three day vacation to find rare sand beetles in a desert region of Japan, a schoolteacher and recreational entomologist (Eiji Okada) misses the last bus back to civilization. A group of villagers offers to put him up for the night with a local widow. He agrees, and they head to the widow’s home, a modest shack located at the bottom of a sandpit. Climbing a rope ladder to get down, he’s greeted by the widow (Kyoko Kishida), who lives alone and eagerly takes his things and prepares him dinner. As he dines, the schoolteacher disregards the widow’s vague comments about the length of his stay being more than just overnight, just as he overlooks the villagers dropping tools into the pit for the woman’s “helper”. At night, she digs sand from the ground into wooden baskets, which are then lifted by the villagers above by a rope and pulley system. The schoolteacher watches and asks if he can help. “Not on the first day,” she replies. He tries again to explain he’s only staying for the night but assumes the misunderstanding is inconsequential. He goes off to bed after she explains her work must continue through the night because “the sand won’t wait.”

In the morning, he finds the woman unreservedly nude and asleep, a towel over her face to protect from the sand that seeps through her roof and ceiling. Her bare body covered in granulated specks, he backs away in shame after regarding her figure. He leaves her some money for the room and board and decides to leave. Now is when he finds the ladder is gone. He tries to climb out from the pit except the steep sand slopes crumble under his weight. He confronts the woman who responds with some embarrassment that he is now a captive to assist with her nightly digging, a task that must be completed to preserve the village. She once had a husband and daughter to assist, but they died during a storm; their bones are buried in the pit, and so she resolves to stay near them. The schoolteacher offers to dig them up and move the grave elsewhere if he’s allowed to go free, but she refuses. Like a captured bug that begins to enjoy its jar, the woman has long since accepted her fate, so much so that we remain unclear if, like the man, she was placed down there by the villagers, or if going down there was her choice to begin with. We are certain, however, that if ever she was presented with the opportunity to escape, she would not take it.

Woman in the Dunes offers no simple understanding of how this village’s economy functions, nor the logic of the why, as the woman claims, if they do not keep digging, the house next door will be in danger. The mechanics do not require rationalization, however; it is enough that those inside the pit do what they’re told. The woman explains the village sells their sand for construction purposes, and they sell it cheap, given its salt content, while the schoolteacher wants to know “Are you shoveling to survive, or surviving to shovel?” After a brief period of rebellion, days and weeks pass, and they settle into a routine consisting of food, work, sleep, and the occasional bath. A single, passionate sexual experience overcomes them, and soon the villagers casually refer to him as the widow’s new husband. The work continues. She saves to buy a radio to keep up with the news and weather reports, but what difference would it make down there except to distract from their pointless existence? And every night there is the sand. The film becomes an alternate take on the Greek myth of King Sisyphus, whose deceit and trickery was punished by Zeus. Damned to a lifetime of hopeless effort, Sisyphus is ordered by Zeus to roll a boulder to the top of a hill; when he reached the top, the boulder would roll down the other side and he had to begin again, on and on like this for all eternity.

Woman in the Dunes offers no simple understanding of how this village’s economy functions, nor the logic of the why, as the woman claims, if they do not keep digging, the house next door will be in danger. The mechanics do not require rationalization, however; it is enough that those inside the pit do what they’re told. The woman explains the village sells their sand for construction purposes, and they sell it cheap, given its salt content, while the schoolteacher wants to know “Are you shoveling to survive, or surviving to shovel?” After a brief period of rebellion, days and weeks pass, and they settle into a routine consisting of food, work, sleep, and the occasional bath. A single, passionate sexual experience overcomes them, and soon the villagers casually refer to him as the widow’s new husband. The work continues. She saves to buy a radio to keep up with the news and weather reports, but what difference would it make down there except to distract from their pointless existence? And every night there is the sand. The film becomes an alternate take on the Greek myth of King Sisyphus, whose deceit and trickery was punished by Zeus. Damned to a lifetime of hopeless effort, Sisyphus is ordered by Zeus to roll a boulder to the top of a hill; when he reached the top, the boulder would roll down the other side and he had to begin again, on and on like this for all eternity.

Teshigahara, Takemitsu, and Abe made a series of four films together in the 1960s; in addition to Woman in the Dunes, there was Pitfall (1962), The Face of Another (1966), and Man Without a Map (1968). They first started working together years before, when Takemitsu produced a series of concerts at the Teshigahara family’s avant-garde flower school Sogetsu, after which Teshigahara asked the composer to create the music for his first film, José Torres (1959), a documentary short about a Puerto Rican boxer training in New York City. Each man was an artist driven by variety. Teshigahara: flower arranger, potter, calligrapher, designer, opera director, documentarian, and later in life he returned to oversee Sogetsu. Takemitsu: composer, musical theorist, philosopher, and poet. Abe: playwright, theater innovator, novelist, and stage director. Theirs was a collaborative relationship where each artist did not hesitate to criticize and help reshape the work of the other. Each member of this trio informed casting, the script, editing choices, and the design of their work. All three were visual artists, Abe having designed a soundless theater movement, while Takemitsu had explored drawing and painting.

Born in 1930 into a family of wealth and considerable historical lineage, Hiroshi Teshigahara was the son of Sofu Teshigahara, a celebrated calligrapher, painter, creator of the renowned Sogetsu school, and a major presence in the Japanese art scene. The director’s upbringing found him raised in a traditional, constraining Japanese home, where he was nonetheless privileged and his intellectual education vast. His collaborators, however, were raised outside of Japan in the comparative wilderness of Manchuria, away from the bustling cityscape of Japan’s main islands. Abe and Takemitsu enjoyed an unconventional upbringing compared to Teshigahara’s. Although both were entered into standard schools, they resisted the plans their fathers had set out for them. Abe was to be a doctor and study at Tokyo University, but he intentionally failed his exams and studied literature instead. Takemitsu’s father wanted his son to follow in his footsteps to become a businessman, except illness prevented him from attending business school, and he studied music from his sickbed, listening to the U.S. occupational forces’ broadcasts of American jazz.

Born in 1930 into a family of wealth and considerable historical lineage, Hiroshi Teshigahara was the son of Sofu Teshigahara, a celebrated calligrapher, painter, creator of the renowned Sogetsu school, and a major presence in the Japanese art scene. The director’s upbringing found him raised in a traditional, constraining Japanese home, where he was nonetheless privileged and his intellectual education vast. His collaborators, however, were raised outside of Japan in the comparative wilderness of Manchuria, away from the bustling cityscape of Japan’s main islands. Abe and Takemitsu enjoyed an unconventional upbringing compared to Teshigahara’s. Although both were entered into standard schools, they resisted the plans their fathers had set out for them. Abe was to be a doctor and study at Tokyo University, but he intentionally failed his exams and studied literature instead. Takemitsu’s father wanted his son to follow in his footsteps to become a businessman, except illness prevented him from attending business school, and he studied music from his sickbed, listening to the U.S. occupational forces’ broadcasts of American jazz.

In the postwar climate of their young adulthood, each of these three artists faced Japan’s growing “kyodatsu condition”, born from the nuclear devastation and ash that now saturated their national identity. As America’s pseudo-democracy enfeebled this proud people, the culture’s former identity was obliterated and left those remaining to ask the question: Who am I? This prevailing existential dilemma became widespread in all forms of Japanese art, leaving themes such as alienation and survival on a war-demolished landscape central to the expressed sentiments of the era. Teshigahara, Takemitsu, and Abe’s collaborations each concerned an existential search to identify the meaning of human existence as it relates to life in then-modern Tokyo—the purpose of existence, the importance of one’s work, one’s place in society at large, and the relationships one maintains. Each of their films follows a protagonist who, through careful allegorical structures, posits these questions and often finds disparaging answers.

In Woman in the Dunes, the sand itself provides many answers, albeit through the film’s allegorical symbolism. With cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa’s wondrous detail of sand and skin, Teshigahara’s film captures every pebble and has a profound understanding of surfaces. When the schoolteacher first arrives in the woman’s home and he wipes away the sand that clings to him, the imagery ignites our senses with a fascinating level of texture. Teshigahara also explores the achingly erotic when he shows the woman’s body dusted in sand; we can imagine how it would feel to touch her, just as we can feel the grit on our neck and sand between our toes. And outside, Teshigahara cuts to sand periodically, to remind us that it has a life of its own. Making the film, the director found he could not create sand slopes at an angle more vertical than thirty degrees, but the pit’s construction looks deep and its angles cavernous. But ripples and waves shot at seemingly dynamic angles move with suspicious intent, seeping downward like a stream from a mountain, but also creeping inside the pit. Mesmerizing transitions between sand and water suggest that little by little the sand will flood and, in effect, drown the protagonist. Segawa’s sharp visual planes make every grain stand out as an individual, but as individuals, they are meaningless. The opening’s microscopic scrutiny of one grain of sand in a trillion, one pointless existence of many, expands to the larger view of the open desert and finds another individual of many, the schoolteacher, as anonymous as a single desert speck.

In Woman in the Dunes, the sand itself provides many answers, albeit through the film’s allegorical symbolism. With cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa’s wondrous detail of sand and skin, Teshigahara’s film captures every pebble and has a profound understanding of surfaces. When the schoolteacher first arrives in the woman’s home and he wipes away the sand that clings to him, the imagery ignites our senses with a fascinating level of texture. Teshigahara also explores the achingly erotic when he shows the woman’s body dusted in sand; we can imagine how it would feel to touch her, just as we can feel the grit on our neck and sand between our toes. And outside, Teshigahara cuts to sand periodically, to remind us that it has a life of its own. Making the film, the director found he could not create sand slopes at an angle more vertical than thirty degrees, but the pit’s construction looks deep and its angles cavernous. But ripples and waves shot at seemingly dynamic angles move with suspicious intent, seeping downward like a stream from a mountain, but also creeping inside the pit. Mesmerizing transitions between sand and water suggest that little by little the sand will flood and, in effect, drown the protagonist. Segawa’s sharp visual planes make every grain stand out as an individual, but as individuals, they are meaningless. The opening’s microscopic scrutiny of one grain of sand in a trillion, one pointless existence of many, expands to the larger view of the open desert and finds another individual of many, the schoolteacher, as anonymous as a single desert speck.

Takemitsu’s soundscape proves just as important as Teshigahara’s depiction of the physical desert, as his music characterizes the sand through severe aural descriptions defining this landscape as a place of mystery and untold terror. More even than the intense visual detail, Takemitsu gives life to the sand through a string ensemble that, later electronically manipulated, stretches out his eerie sounds to represent the image of sand slowly shifting down a hillside. His strings, interrupted by abrupt percussion spasms, call out in the sand’s voice. Even when their cries are not evident and screeching, Takemitsu uses an ever-present whirr so that we cannot settle into this nightmarish situation. In a later scene, the schoolteacher wants to make a bargain with the villagers to see the ocean for a short time every day; they agree, but only if he will perform sexual acts with his “wife” out in the open. The village audience assembles, appearing around the top of the pit like gargoyles peering down. All at once, the villagers’ machine-like drumming from Onigoroshi-daiko (demon-killing drums) throb and the schoolteacher attempts to force himself on the woman. In this moment they are both reduced to an inhuman spectacle, stripping away any semblance of humanity left in the schoolteacher. Takemitsu’s drums define the moment, just as his strings echo the faint calls of the living sand.

The schoolteacher’s resigned fate mirrors the widow’s when he finds a reason for himself to forever remain in the pit. Just as the widow’s buried family keeps her there, the schoolteacher discovers a way of drawing water from the damp sand by burying and covering a bucket, a device originally designed to catch birds. Through his method, they will no longer need the villagers to supply them with water. But soon the woman has become pregnant, and she must be taken to a doctor. In the villagers’ rush to move her, they forget to pull up the ladder. The schoolteacher’s chance to escape awaits, but now he has a purpose to stay down there, if only to thwart the villagers with his pump. Doing this becomes more important than escape; he chooses to stay and brood over when he will reveal his subversive device to those in power. In time, he resolves. As Woman in the Dunes relates to a larger view of contemporary life, this revelation may be interpreted as a worthy consolation, that some comfort in his existence is better than none at all. But in taking what he can get, he ignores the bigger picture: that he’s still trapped inside a hopeless pit from which there is no escape. Perhaps it comes down to whether the viewer is an optimist or cynic, but the film presents such a meaningless reality for this man that one cannot help but view the parable as a horrific commentary on the hollow nature of the average life, droning through humdrum domestic routines, reporting back to the same dead-end job every day, and savoring those little rewards as minor victories. What a wretched view.

The schoolteacher’s resigned fate mirrors the widow’s when he finds a reason for himself to forever remain in the pit. Just as the widow’s buried family keeps her there, the schoolteacher discovers a way of drawing water from the damp sand by burying and covering a bucket, a device originally designed to catch birds. Through his method, they will no longer need the villagers to supply them with water. But soon the woman has become pregnant, and she must be taken to a doctor. In the villagers’ rush to move her, they forget to pull up the ladder. The schoolteacher’s chance to escape awaits, but now he has a purpose to stay down there, if only to thwart the villagers with his pump. Doing this becomes more important than escape; he chooses to stay and brood over when he will reveal his subversive device to those in power. In time, he resolves. As Woman in the Dunes relates to a larger view of contemporary life, this revelation may be interpreted as a worthy consolation, that some comfort in his existence is better than none at all. But in taking what he can get, he ignores the bigger picture: that he’s still trapped inside a hopeless pit from which there is no escape. Perhaps it comes down to whether the viewer is an optimist or cynic, but the film presents such a meaningless reality for this man that one cannot help but view the parable as a horrific commentary on the hollow nature of the average life, droning through humdrum domestic routines, reporting back to the same dead-end job every day, and savoring those little rewards as minor victories. What a wretched view.

The film’s Kafkaesque hero is pinned down like one of his bugs on display, to be studied and cataloged, and the most terrible turn is when we realize that this human insect begins to enjoy the pin sticking through him and limiting his existence to something manageable with understandable controls. As the schoolteacher laments earlier in the film, so much of life is dedicated to proving to others that we are who we say we are. “The certificates we use to make certain of one another: contracts, licenses, ID cards, permits, deeds, certifications, registrations…” His list goes on and on. “Is that all of them?” he asks. “Men and women all slaves to their fear of being cheated. In turn, they dream up new certificates to prove their innocence. No one can say where it will end.” This was true in postwar Japan, but even more so today, where these items are now electronically cataloged on “the grid” from which it is so difficult to escape. But how many of us truly understand the ways in which we have deceived ourselves with such constraints? And how many of us betray our own desires every day by eking out some pitiable sense of purpose in the most mundane of ways?

As with any great allegory, Woman in the Dunes posits these questions but provides no answers. They remain riddles in the sand. For Japanese viewers in 1964, the schoolteacher embodies postwar concerns, and this experimental film presents them in grave, artistic dimensions. The universality of such themes and their unique, unforgettably hypnotic representation resulted in international attention for both Woman in the Dunes and the filmmakers. The picture won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes in 1964 and received two Oscar nominations (Best Director and Best Foreign Language Film). Today the film represents something far more expansive by way of a commentary on domestic claustrophobia, and the illusions we imagine to convince ourselves we are not trapped. But the incredible formal discipline of artists Teshigahara, Abe, and Takemitsu binds us to the film on sensory levels not typically associated with cinema. Their treatment of the sand and sound in symbolic terms results in an unforgettable parable, a picture that remains one of the great cinematic evocations of the rhythm of life, and humanity’s obligation to give life purpose by breaking free of that rhythm.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review