The Definitives

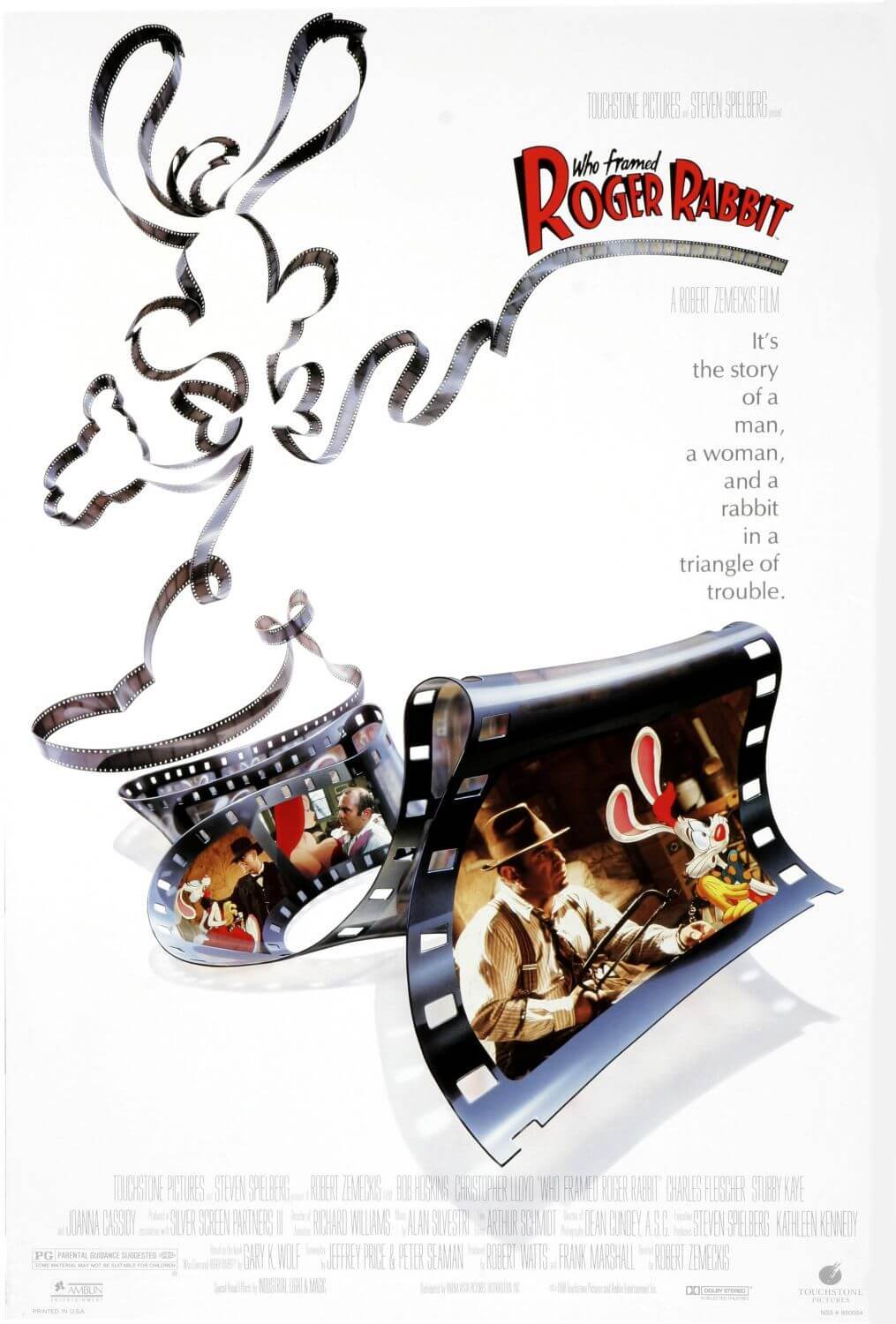

Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s first sequence epitomizes the film’s seamless fusion of live-action and traditional hand-drawn animation, of noirish plotting and zany cartoon antics: The faces of Baby Herman and Roger Rabbit fill the screen in an introduction to the Maroon Cartoon called “Somethins’ Cookin’,” about a beleaguered bunny babysitter placed in charge of a cookie-hungry kiddo. Reminiscent of MGM’s 1956 Tom and Jerry short “Busy Buddies,” and others in which the cat and mouse scramble to keep up with a wandering infant, Roger faces a flaming stovetop, high-speed kitchen utensils, and an electrical socket while he’s in pursuit of the curious tyke. All at once, Roger blows it. Inside a refrigerator that was dropped on his head, he sees birdies instead of stars. The camera pulls back to reveal a three-dimensional studio set inhabited by the cartoon characters. The live-action director Raoul J. Raoul tosses his script to the ground, shouts about Roger’s failure to remember his cues, and calls lunch for the exhausted crew. Observing the shoot, private eye Eddie Valiant (Bob Hoskins) grumbles, “Toons.” Then, Valiant walks off the set to meet with studio head R.K. Maroon (Alan Tilvern) to discuss a job. He’s tasked with investigating a rumor that Roger’s wife might be unfaithful, which has been distracting the studio’s top star—and if it’s true, Valiant will snap a few dirty photos. In a few minutes of screentime, director Robert Zemeckis has created a dazzling synthesis of so-called Toons and the comparative real world through a heightened cartoon fantasy and atmospheric film noir.

Released in 1988 after years of intensive effort and experimentation, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a technical marvel even in today’s cinema where computers do most of the complex work. Containing over 50 minutes of animation and using minimally tested techniques, the film’s specific blend of formats has been imitated yet never matched. But it’s not content with breaking boundaries in form alone; it also innovates with a distinct mixture of genres. It combines a moody mystery and Toon hijinks in a manner then untried and potentially uncommercial. The storyline involves murder, sex, and corruption interspersed between the sort of slapstick humor and gags usually aimed at youngsters. The hero, Valiant, a former “Detective to the Stars,” can barely resist salivating at the sight of a drink ever since a Toon dropped a piano on his late brother’s head. Not only does Valiant introduce alcoholism and trauma into the proceedings, but his past suggests that the cartoons of yesteryear might be capable of real murder. To be sure, though it was distributed by Disney’s more mature Buena Vista Pictures and hails from a period of 1980s commercial entertainment, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is unconventional material.

Perhaps most of all, it’s the best film to understand what drives Zemeckis as a filmmaker—even auteur—despite his penchant for mainstream projects. It’s the film that exemplifies his directorial tendencies identified by Norman Kagan in his book The Cinema of Robert Zemeckis: his experimentation with technology, use of broad humor, and cynical commentary on the world. Though, these qualities tend to emerge inconsistently, usually in his earlier personal works, whereas his recent efforts feel comparatively impersonal or lacking in these areas. Moreover, Zemeckis’ unique balance of boundary-pushing comedy and technical innovation on Who Framed Roger Rabbit supplies the masses with a new experience that, unlike its successors, avoids alienating the audience. For instance, many others have tried to reproduce the film’s distinct formula, adding more of film noir ingredient A and less of cartoon ingredient B. Call it restraint or a precise understanding of the material’s tone, but Zemeckis serves both masters, the noir and the cartoon, so his film is a celebration of both. By contrast, Ralph Bakshi’s Cool World (1992) steps too far into the exploitative arena of crime and sex, and the meeting of puppets and a buddy cop movie in The Happytime Murders (2018) pushed the material beyond the R-rated edge. It’s easy to aim sex, violence, and crude humor at adults; it’s something else altogether to walk the fine line between the two and deliver something subversive and new to a mass audience.

To recognize how Who Framed Roger Rabbit reflects its director’s sensibilities, it’s necessary to understand Zemeckis, a filmmaker who has always been interested in commercial entertainment—in part because that’s what he grew up watching. Born in 1954, he was raised in Chicago, the son of a construction worker in a blue-collar family uninterested in the arts. Like many children of his generation, television was his third parent, feeding him a diet of The Three Stooges, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and Jerry Lewis during the day, and schlocky horror aired late at night. He particularly admired William Castle, a master of gimmicks such as seat buzzers and Smell-O-Vision, whose House on Haunted Hill (1959) is often cited as Zemeckis’ favorite film. Using his parents’ 8mm camera, he experimented with technique, learning what he could from observing television and testing from there. When he eventually transferred to the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts to become a director, he did so admiring what he called the “George Lucas Class” of the New Hollywood, including filmmakers several years ahead like Francis Ford Coppola, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg. These directors made larger-than-life entertainments, including The Godfather (1974) and Jaws (1975), with daring formal choices and accessible storytelling. Alongside fellow USC student and later writing partner Bob Gale, Zemeckis rejected the intellectualism of university film students who lionized arthouse masters and film theory. He wanted to make the kind of stories he grew up watching.

To recognize how Who Framed Roger Rabbit reflects its director’s sensibilities, it’s necessary to understand Zemeckis, a filmmaker who has always been interested in commercial entertainment—in part because that’s what he grew up watching. Born in 1954, he was raised in Chicago, the son of a construction worker in a blue-collar family uninterested in the arts. Like many children of his generation, television was his third parent, feeding him a diet of The Three Stooges, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, and Jerry Lewis during the day, and schlocky horror aired late at night. He particularly admired William Castle, a master of gimmicks such as seat buzzers and Smell-O-Vision, whose House on Haunted Hill (1959) is often cited as Zemeckis’ favorite film. Using his parents’ 8mm camera, he experimented with technique, learning what he could from observing television and testing from there. When he eventually transferred to the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts to become a director, he did so admiring what he called the “George Lucas Class” of the New Hollywood, including filmmakers several years ahead like Francis Ford Coppola, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg. These directors made larger-than-life entertainments, including The Godfather (1974) and Jaws (1975), with daring formal choices and accessible storytelling. Alongside fellow USC student and later writing partner Bob Gale, Zemeckis rejected the intellectualism of university film students who lionized arthouse masters and film theory. He wanted to make the kind of stories he grew up watching.

Consider A Field of Honor, Zemeckis’ first short film from 1973 that plays like an episode of Tales from the Crypt (a show he helped develop for HBO). The story, co-written by Zemeckis and Gale, follows a former mental patient who returns to the world to find it wrought with cops chasing protestors, bus hijackings, cops shooting unarmed criminals, polygamy, and his well-armed veteran father preparing for an alien invasion. It’s all set to the theme from The Great Escape (1963), an ironic twist given the patient’s reaction: he goes on a brief killing spree before happily returning to the asylum. Zemeckis and Gale would continue writing darkly comical stories together, many of which combined broad humor and social commentary in rebellious ways. After a brief stint as concept writers on Kolchak: The Night Stalker, they started working for Milius as a writing team. Their first script, an anti-church vampire yarn entitled Bordello of Blood, was rejected (it would be made in 1996 as a Tales from the Crypt feature). Meanwhile, A Field of Honor earned Spielberg’s attention (because Zemeckis tracked Spielberg down and forced him to watch it), and almost immediately, the trio collaborated on several projects. Spielberg executive produced the Zemeckis-Gale scripts I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978) and Used Cars (1980)—two equally ambitious, zany, thrilling, crude, and hilarious comedies set in distinct worlds (their unofficial motto: “social irresponsibility”)—with Zemeckis directing and Gale co-writing. Spielberg himself directed their script 1941 (1979), a raucous World War II comedy about Hollywood’s paranoid response to the threat of a Japanese invasion.

Each of these early, unbridled projects reveals Zemeckis’ sustained interest in pop culture, exaggerated humor, and disorderly setups, giving way to a sense of outlandish yet organized chaos. But none of them made much money or critical favor. Instead, it took another four years of Zemeckis and Gale working on unrealized scripts for the likes of Spielberg and Brian De Palma before Zemeckis could redeem himself as a commercially viable filmmaker with Romancing the Stone (1984). Using that film’s unexpected success as proof of Zemeckis’ bankability, Spielberg helped Zemeckis and Gale set up their long-gestating script for Back to the Future at his production company, Amblin Entertainment, for release by Universal in 1985. The film would become one of the highest-grossing Hollywood productions ever at that time. And with only a few titles under his belt, Zemeckis’ signatures became undeniable. He demonstrated a penchant for nostalgia, an obsession with camera tricks and technology, an almost juvenile sense of bawdy humor, and a low viewpoint on humanity—yet he wrapped those impulses inside wildly entertaining packages of Hollywood storytelling. Gale once described Zemeckis as having “an outrageous sense of humor, a great sense of showmanship, and a healthy cynicism about the world.” Who better to make Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

The project started as Who Censored Roger Rabbit, a novel by Gary K. Wolf, published in 1981 and almost immediately optioned by Disney. The book takes place in the modern-day world of comic strip cartoons, suggesting that Toons speak in talk bubbles, exist in three dimensions, and appear in comic strips captured with photography. The screenplay by Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman resituates the setting to 1947, which not only steeps the material in period nostalgia popular during the 1980s as Baby Boomers reconsidered their formative years, but it also makes the concept more palatable. “It helps you believe,” said Zemeckis, “if it’s once upon a time.” Years passed without progress given the production’s estimated costs and the vast technical challenges involved, which scared off potential directors like Terry Gilliam. But Michael Eisner hoped to reinvigorate Disney’s struggling animation division with the proposed blend of live-action and animation. It ultimately took Steven Spielberg, then at the height of his influence in Hollywood, to solidify Disney and Warner Bros.’s interest to greenlight the film. Serving as executive producer, Spielberg convinced Disney to cover the film’s $50 million budget and Warner Bros. to loan out their most popular Looney Tunes—marking the first occasion where Daffy and Donald Duck would play dueling pianos or Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny could collaborate on a disturbing “spare” parachute prank on Valiant. Zemeckis was eager to play in this world, even though it meant coordinating several layers of filmmaking technique into a seamless whole: hand-painted animation cells supervised by veteran animator Richard Williams, costing $250,000 for every minute of screentime; Industrial Light & Magic’s layering of special effects that gave the animation depth; and live-action footage in which actors appeared to engage with two-dimensional characters and worlds.

The project started as Who Censored Roger Rabbit, a novel by Gary K. Wolf, published in 1981 and almost immediately optioned by Disney. The book takes place in the modern-day world of comic strip cartoons, suggesting that Toons speak in talk bubbles, exist in three dimensions, and appear in comic strips captured with photography. The screenplay by Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman resituates the setting to 1947, which not only steeps the material in period nostalgia popular during the 1980s as Baby Boomers reconsidered their formative years, but it also makes the concept more palatable. “It helps you believe,” said Zemeckis, “if it’s once upon a time.” Years passed without progress given the production’s estimated costs and the vast technical challenges involved, which scared off potential directors like Terry Gilliam. But Michael Eisner hoped to reinvigorate Disney’s struggling animation division with the proposed blend of live-action and animation. It ultimately took Steven Spielberg, then at the height of his influence in Hollywood, to solidify Disney and Warner Bros.’s interest to greenlight the film. Serving as executive producer, Spielberg convinced Disney to cover the film’s $50 million budget and Warner Bros. to loan out their most popular Looney Tunes—marking the first occasion where Daffy and Donald Duck would play dueling pianos or Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny could collaborate on a disturbing “spare” parachute prank on Valiant. Zemeckis was eager to play in this world, even though it meant coordinating several layers of filmmaking technique into a seamless whole: hand-painted animation cells supervised by veteran animator Richard Williams, costing $250,000 for every minute of screentime; Industrial Light & Magic’s layering of special effects that gave the animation depth; and live-action footage in which actors appeared to engage with two-dimensional characters and worlds.

Technological limitations dictated how the camera and human cast could move in earlier attempts to blend live-action performers and cartoon characters. When Gene Kelly dances with Jerry Mouse in Anchors Aweigh (1945), the camera remains either stationary or moves along a horizontal line with the dancers to minimize animation challenges. When the titular nanny in Mary Poppins (1964) leaps into a two-dimensional cartoon world, the actors perform against a yellow screen (an ancestor of today’s green screen technology), which would be filled-in with hand-drawn animated surroundings. Similar techniques were used in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) and the 1977 version of Pete’s Dragon. Still, in each example, the actors were limited to straightforward movements to make the animators’ job easier. The result looks rather staid in terms of camera placement, allowing the interaction of humans and cartoons to take center stage. Zemeckis demanded more for Who Framed Roger Rabbit, insisting that his camera should move liberally to guide the viewer’s eye and emotion, offering a sharp alternative to the limited visual standards of these earlier examples. Producer Frank Marshall noted Zemeckis’ attitude: “‘I’m going to shoot this movie just like a regular movie, and you guys figure out how to put the Toons in.’”

The resultant technique, dubbed “multidimensional interactive character generation,” meant the live-action scenes would be shot first and the animation added afterward. Zemeckis captured scenes with his usual proclivity for fluid camerawork, sometimes employing long and complex takes that maneuvered around interior spaces or through the streets of Los Angeles, sometimes using quick editing that would require animators to shift perspective. Williams’ team of animators was accustomed to symmetrical framing and simple pans, and Zemeckis’ willingness to move the camera with the story’s action tested their talents. Williams recognized how the power of animation had been curtailed by studios and filmmakers unwilling to invest in a more visually active and expensive product, and he welcomed the challenge, even if it meant months of extra work. What’s more, despite the extensive pre-planning required for a typical blend of live-action and animation, Zemeckis did not eliminate on-set improvisation; he often came up with spontaneous new gags or comic asides on the spot, requiring ILM and the animation team to add to their schedule beyond what was initially scripted and storyboarded.

The performers faced unique challenges as well, such as acting opposite thin air. Zemeckis required the cast to train in pantomime to convey the presence of characters or the weight of objects that were not there. Hoskins, an extraordinarily talented performer but no one’s first choice to play Valiant (Harrison Ford, Eddie Murphy, and Bill Murray turned down the part), shares the most screentime with Toons. And in each scene, the viewer believes that Hoskins believes Roger is there—and sometimes he was, played by Richard Fleischer, the voice of Roger Rabbit, in a bunny suit—making the illusion flawless. Over the five-month shoot, Hoskins had spent so much time visualizing Roger and other cartoons that he began to see them. “The hallucination began to take over,” he told Newsweek. For other characters, Zemeckis had actual-size mannequins made so the actors had something to connect their eyes to, eliminating how performers often appear to be looking into empty space when interacting with a cartoon character. To complete the illusion, Zemeckis also used old-fashioned techniques like transparent wire or mechanical doors, tricks established decades earlier for The Invisible Man (1933), to move objects around the set as Toons interact with them. Robot arms, later covered by animation, moved props to complete more elaborate gestures—so when Roger breaks plates over his own head or a weasel shoves a gun in Valiant’s back, a small animatronic device carries out the action. Once Zemeckis captured the live-action footage, the post-production process required thousands of hand-drawn animated cells, combined with ILM’s addition of shadows, tones, and layers to the animation, creating optical composites that took over a year to complete.

The performers faced unique challenges as well, such as acting opposite thin air. Zemeckis required the cast to train in pantomime to convey the presence of characters or the weight of objects that were not there. Hoskins, an extraordinarily talented performer but no one’s first choice to play Valiant (Harrison Ford, Eddie Murphy, and Bill Murray turned down the part), shares the most screentime with Toons. And in each scene, the viewer believes that Hoskins believes Roger is there—and sometimes he was, played by Richard Fleischer, the voice of Roger Rabbit, in a bunny suit—making the illusion flawless. Over the five-month shoot, Hoskins had spent so much time visualizing Roger and other cartoons that he began to see them. “The hallucination began to take over,” he told Newsweek. For other characters, Zemeckis had actual-size mannequins made so the actors had something to connect their eyes to, eliminating how performers often appear to be looking into empty space when interacting with a cartoon character. To complete the illusion, Zemeckis also used old-fashioned techniques like transparent wire or mechanical doors, tricks established decades earlier for The Invisible Man (1933), to move objects around the set as Toons interact with them. Robot arms, later covered by animation, moved props to complete more elaborate gestures—so when Roger breaks plates over his own head or a weasel shoves a gun in Valiant’s back, a small animatronic device carries out the action. Once Zemeckis captured the live-action footage, the post-production process required thousands of hand-drawn animated cells, combined with ILM’s addition of shadows, tones, and layers to the animation, creating optical composites that took over a year to complete.

Surprisingly, the ambitious technical undertaking of Who Framed Roger Rabbit does not rob the material of its vital energy or noirish undertones. The milieu, accented by Alan Silvestri’s score that alternates between jazzy and madcap, offers a throwback to two distinct areas popular during Hollywood’s Golden Age: the shadowy films of the postwar reconstruction period and the Looney Tunes, Merrie Melodies, and other cartoon shorts that originally appeared before them. Toons like Roger and Baby Herman have been lovingly designed from classical influences like Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse, although their movements pay homage to Tex Avery’s style—rife with physical exaggerations and comic violence that seems, well, cartoonish next to the lower-key mood of Chuck Jones cartoons. Serving as animation director, Williams explained that Zemeckis “wanted three things: Disney articulation (i.e., believability, weight, skill of movement, and sincerity when we needed it); Warner Bros. characters, because they’re zanier, they do more interesting things; and Avery humor.” As a result, the film’s Toons will do anything for a laugh, making some scenes feel almost chaotic with their impulsive, rambunctious behavior that also looks tactile. The effect even drives the story when Valiant finds himself handcuffed to Roger, who can only free himself when it’s funny—at the moment when Valiant struggles to saw himself free.

Toons, Roger above all, behave as though they’re aware of an audience outside of the diegesis, and they calibrate their action to entertain that audience. When Valiant drives into Toontown, the scenery and characters seem to be performing an ever-playing cycle of brightly colored comic routines, as though their very existence derives meaning from the performer-audience relationship and less as a response to Valiant or anyone inside the diegesis. When Valiant first steps onto the Maroon Cartoon backlot, we see familiar faces (Dumbo, Michigan J. Frog, the brooms from Fantasia, et al.) interacting with their surroundings—an obligatory passage for any picture with a scene on a studio lot—performing sight gags in the background. Who are these performances for, other than the audience, and not even the spectators in the film, but the viewer of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Curiously, there is no suggestion that this state represents forced servitude or that the Toon is locked inside a one-way arrangement of indentured servitude or slavery to the humans in the diegesis. The film makes no mention of the Toons’ creator(s) or how they live and inhabit the three-dimensional plane (though the formula of Dip, a substance designed to kill Toons, includes chemicals typically used as paint thinner, suggesting the Toons have been painted). Looking at onscreen evidence, the Toon appears to live for us, while the film views most of them as innocents.

The Toons’ status as a wholesome, entertainment-driven species creates a sharp contrast to the noir story elements. In a conspiracy resembling the plot of Chinatown (1974), the resident villain, Judge Doom (Christopher Lloyd), uses a company called Cloverleaf to buy Los Angeles’ public transit trolley system, Pacific Electric Railway. His elaborate scheme also entails framing Roger for murder to acquire ownership of Toontown from Marvin Acme (Stubby Kaye), the man playing “patty-cake” with Roger’s wife, the voluptuous Jessica Rabbit (voiced by Kathleen Turner). Doom’s master plan is to eventually own and wipe out Toontown, replacing it with a freeway to Pasadena lined with “a string of gas stations, inexpensive motels, restaurants that serve rapidly prepared food.” The scheme recalls the vast conspiracy at the intersection of water irrigation, land development, politics, and power in Chinatown. Like that film, the conspiracy in Who Framed Roger Rabbit has some bearing in historical fact. General Motors and other automobile companies purchased the streetcar companies only to dissolve them and ensure their own industry. In any case, the film’s neo-neo-noir script went through several drafts before settling on this conflict, some with Baby Herman as the villainous mastermind, others with Jessica Rabbit as the culprit.

The Toons’ status as a wholesome, entertainment-driven species creates a sharp contrast to the noir story elements. In a conspiracy resembling the plot of Chinatown (1974), the resident villain, Judge Doom (Christopher Lloyd), uses a company called Cloverleaf to buy Los Angeles’ public transit trolley system, Pacific Electric Railway. His elaborate scheme also entails framing Roger for murder to acquire ownership of Toontown from Marvin Acme (Stubby Kaye), the man playing “patty-cake” with Roger’s wife, the voluptuous Jessica Rabbit (voiced by Kathleen Turner). Doom’s master plan is to eventually own and wipe out Toontown, replacing it with a freeway to Pasadena lined with “a string of gas stations, inexpensive motels, restaurants that serve rapidly prepared food.” The scheme recalls the vast conspiracy at the intersection of water irrigation, land development, politics, and power in Chinatown. Like that film, the conspiracy in Who Framed Roger Rabbit has some bearing in historical fact. General Motors and other automobile companies purchased the streetcar companies only to dissolve them and ensure their own industry. In any case, the film’s neo-neo-noir script went through several drafts before settling on this conflict, some with Baby Herman as the villainous mastermind, others with Jessica Rabbit as the culprit.

Regardless of the many revisions, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a tightly structured classical noir script. Every line of dialogue sets up a subsequent plot detail or comic reward; every detail on the screen has a payoff later in the film. Within its noir structure, the script also creates distinct characters. Roger is the sprightly, tender-hearted comic relief. Doom is a terrifying figure of authority, garbed in black and disguised to hide the monstrous, murderous, high-pitched Toon underneath. The most famous of them is Jessica Rabbit, the self-aware red herring and femme fatale (“I’m not bad. I’m just drawn that way,” she remarks). Jessica remains the focus of much analysis about Who Framed Roger Rabbit, owing to her unconventional representation as a two-dimensional sexpot who draws the eyes of Toons and humans alike. She’s an amalgam of Marilyn Monroe’s curves, Veronica Lake’s peek-a-boo hairstyle, Lauren Bacall’s sultry voice, and Rita Hayworth’s duplicity in The Lady from Shanghai (1947). All of these influences have been contained in a character design inspired by the titular character in Tex Avery’s “Red Hot Riding Hood” (1943). (Alternatively, Avery’s “Little Rural Red Riding Hood” (1949) offers the origins of her frightening counterpart, Lena Hyena, the man-crazy Toon who plants a smooch on Valiant in Toontown.) But after years of endless discussion about Jessica Rabbit’s sex appeal, her role in the film’s success has been overestimated. Instead, consider Hoskins’ presence as Valiant: the unlikely, down-on-his-luck hero whose tentative romance with the no-nonsense bartender Dolores (Joanna Cassidy) proves endearing. Title notwithstanding, Valiant’s character arc and Hoskins’ committed performance propel the film.

While earning over $150 million at the U.S. box office, the contemporary critical response to Who Framed Roger Rabbit was mixed and usually accompanied by discussions about the production’s technical accomplishment and entertainment value, followed by an entrenched analysis of how the film handles the interplay between the human and Toon worlds. Roger Ebert celebrated its story and technique as “not only great entertainment but a breakthrough in craftsmanship.” In The New York Times, Janet Maslin praised how Zemeckis takes “thrilling steps into another dimension” that “must be seen to be believed.” John Simon of the National Review disagreed, calling the production “a film for technology’s sake, and so, ultimately a case of the tail wagging the rabbit.” Some dismissed the appeal of Roger Rabbit, such as Variety’s Brit, who wrote, “the story itself amounts to little more than inspired silliness.” Critics also noted the curious sex appeal of Jessica Rabbit, such as Jonathan Rosenbaum in the Chicago Reader, who underlined how her quality of “bestiality” and “fetishism” muddled the character in a strange blend of fantasies (a reference to Jessica’s declaration to Roger, “I’ve loved you more than any woman’s ever loved a rabbit”). Writers also observed the sociological dynamics between the species, making lofty comparisons to issues of race. Los Angeles Daily News critic Michael Healy wrote, “The way humans talk about toons is derived from the way prejudiced whites talk about blacks—carefree fools, simpletons, happy-go-lucky stereotypes—before the civil rights movement. One doesn’t have to be overly sensitive for this conceit to make one’s skin crawl.” In his book about Zemeckis, Norman Kagan furthers this notion, suggesting the human characters “see nothing wrong with segregation” and the film amounts to “history’s nightmare transformed by Hollywood into jokey entertainment.”

Arguments against the film’s treatment of Toons, and theories about whether they represent marginalized cultures, are not entirely unfounded. Ghettoized in Toontown, where they remain desperate for approval and desperate for a laugh, the Toons could represent any non-white race forced to endure institutionalized racism or racial violence throughout U.S. history. Worse, Toons deserve less-than-human treatment in the eyes of the law, evidenced when Judge Doom slowly submerges a Toon shoe in a vat of Dip. Valiant and some cops watch, horrified, as the puppy-like shoe melts in a chemical bath, screaming for its life, with apparently no recourse to object. But theories about the film as a metaphor for race in America ignore the finale’s details. Valiant’s endeavor to stop Judge Doom’s plan to eliminate Toontown and build a freeway is not about preserving segregation or keeping Toons and humans separate. Rather, it’s about preventing Doom from wiping out Toontown altogether. The film does not end with an edict that requires all Toons to live inside of Toontown’s borders. Acme’s will gives the Toons ownership of their own municipality, though they’re free to continue living and working outside its walls. What the film captures is Valiant’s willingness, and thus our own, to see the Toons as living beings worthy of love, life, and self-governance, thus revealing the humanity that he has kept at bay with booze. If the film sees the Toons as a marginalized race, the film is anti-segregationist—it ends with the wall between Toontown and Los Angeles crumbling—and hopes for their rights alongside human beings. However, the wall imagery suggests a closer resemblance to contemporary Cold War politics and the Berlin Wall’s eventual destruction to bring two communities closer together.

Arguments against the film’s treatment of Toons, and theories about whether they represent marginalized cultures, are not entirely unfounded. Ghettoized in Toontown, where they remain desperate for approval and desperate for a laugh, the Toons could represent any non-white race forced to endure institutionalized racism or racial violence throughout U.S. history. Worse, Toons deserve less-than-human treatment in the eyes of the law, evidenced when Judge Doom slowly submerges a Toon shoe in a vat of Dip. Valiant and some cops watch, horrified, as the puppy-like shoe melts in a chemical bath, screaming for its life, with apparently no recourse to object. But theories about the film as a metaphor for race in America ignore the finale’s details. Valiant’s endeavor to stop Judge Doom’s plan to eliminate Toontown and build a freeway is not about preserving segregation or keeping Toons and humans separate. Rather, it’s about preventing Doom from wiping out Toontown altogether. The film does not end with an edict that requires all Toons to live inside of Toontown’s borders. Acme’s will gives the Toons ownership of their own municipality, though they’re free to continue living and working outside its walls. What the film captures is Valiant’s willingness, and thus our own, to see the Toons as living beings worthy of love, life, and self-governance, thus revealing the humanity that he has kept at bay with booze. If the film sees the Toons as a marginalized race, the film is anti-segregationist—it ends with the wall between Toontown and Los Angeles crumbling—and hopes for their rights alongside human beings. However, the wall imagery suggests a closer resemblance to contemporary Cold War politics and the Berlin Wall’s eventual destruction to bring two communities closer together.

The reviews of Who Framed Roger Rabbit also anticipate how, for the remainder of his career, Zemeckis would be saddled with the label of a technophile more interested in experimenting with the cinematic apparatus than telling a good story. If this is true, it’s certainly more evident in his twenty-first century work. Examples from the first half of his career regularly feature his authorial signatures, including his penchant for broad humor and a healthy skepticism about the goodness of humanity and its institutions. These qualities remain unmistakable in I Wanna Hold Your Hand, Used Cars, Death Becomes Her (1992), Forrest Gump (1994), Contact (1997), and Allied (2016). Among these examples, Who Framed Roger Rabbit pushes technology furthest, contains unabashedly cartoonish humor, draws its morality from the ambiguities of film noir, and questions the integrity of law enforcement and corporate greed. His later experiments with animation and performance captured in The Polar Express (2004), Beowulf (2007), A Christmas Carol (2009), and Welcome to Marwen (2018) often result in visually disappointing outcomes that have little to say about the world and feature technology that overwhelms the story. Even his relatively straightforward films such as Cast Away (2000) and Flight (2012) offer visual trickery of another kind—bravado plane crash sequences in both quicken the pulse, yet the central performances by Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington, respectively, deliver a different type of special effect. But few examples from his career, apart from Allied or What Lies Beneath (2000), prove as cynical about systems of authority as Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

Watching the film more than thirty years after its release, Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s pure energy, mistrust of the system, and countless delights almost outshine how it revolutionized the mixture of animated characters in the human world. From a historical outlook, what remains so fascinating is how, even though successors like Space Jam (1996), Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003), or Tom & Jerry (2021) are aided by less strenuous computer technology, the result has never been as seamless, kinetic, or entertaining as Zemeckis’ breakthrough. The film is not merely the first of a kind but a true original, occasionally imitated but never matched. Unlike other, hollow attempts to capitalize on intellectual properties with the convergence of live-action and animation, Who Framed Roger Rabbit feels like a work of passion and craft. Zemeckis supplies an unlikely personal touch that leaves this big-budget studio project feeling like an extension of his creative, madcap, cynical, and technology-obsessed sensibilities. Contained in the film’s commingling of kooky humor, formal bravado, and portrait of America’s corrupt institutions resides a familiar set of traits found throughout the director’s body of work. Without Zemeckis at the helm, the film may have felt engineered; instead, it feels inspired.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

“Behind the Ears: The True Story of Roger Rabbit.” DVD. Buena Vista Home Entertainment, 2003.

Kagan, Norman. The Cinema of Robert Zemeckis. Taylor Trade Publishing, 2003.

Williams, Richard. “The Time Is Right: A Talk with Richard Williams.” Animation, vol. 2, no. 1, Summer 1988.

Zemeckis, Robert. “Guilty Pleasures.” Film Comment, January-February, 1995.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review