The Definitives

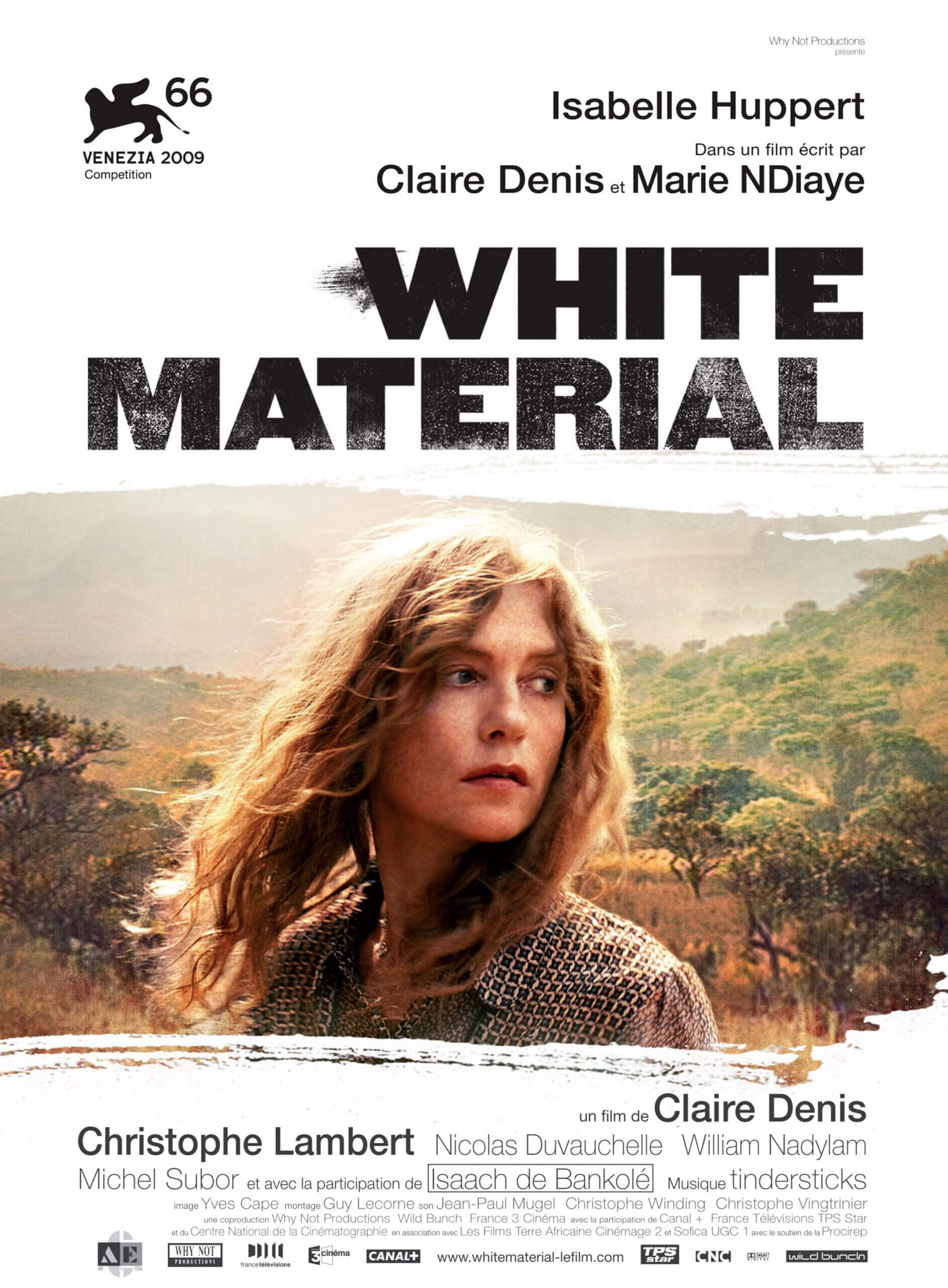

White Material

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The cinema of Claire Denis cuts into the essential core of its subject matter with unflinching reality. An example of this occurs in White Material, as the camera regards Isabelle Huppert in a morning ritual scene that might seem commonplace except for what it reveals about the central character. Maria Vial, a white farmer on a coffee plantation in postcolonial Africa, is willfully oblivious to the oncoming surge of rebels who seek to overthrow the unstable government and destroy any signs of white outsiders. Denis observes Maria’s body as the character prepares herself for the day, applying a layer of fleshy crimson lipstick and zipping up her pink dress. As the shot looks over Maria from head to toe, the viewer will notice that she has painted her toenails, a detail that seems absurd given the situation unfolding around her plantation. Maria is a French character so entrenched in a colonial ideology and sense of ownership over the plantation that she jealousy defends what she deems to be her land. Not only is she heedless to the inevitable wave of violence coming her way, to the extent that she prepares her appearance for an average workday, but she still feels as though the plantation is her home. It’s a moment that reveals Maria’s blindness to all except the matters referred to by the title.

Many of Denis’ films tackle questions of belonging and displacement, and her best, arguably most personal films explore race and colonialism alongside such questions. White Material is set in French West Africa, just as her earlier masterpieces Chocolat (1988) and Beau travail (1999) were, and it’s a setting with which she’s familiar. After she was born in Paris in 1948 to French parents, Denis’ father, a colonial functionary, moved their family to West Africa, where she lived in various French-dominated countries until her mid-teens. Although her parents were among the white colonizers in Africa, Denis has described them in interviews as being critical of imperialist ideologies. Unlike many of the French in Cameroon, Djibouti, or Senegal—all countries where she lived in her African upbringing—Denis and her parents were able to see beyond whiteness and otherness, acknowledging the human identities around them and thus see to the margins of these colonized countries. At a young age, Denis was acutely aware of the relationship between Africans and the French, the black-skinned and the white, and she came to see that relationship as warped due to matters of race and economy. When several independence movements sprang up across Africa in the 1950s, Denis’ family moved back to France.

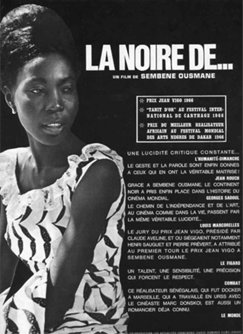

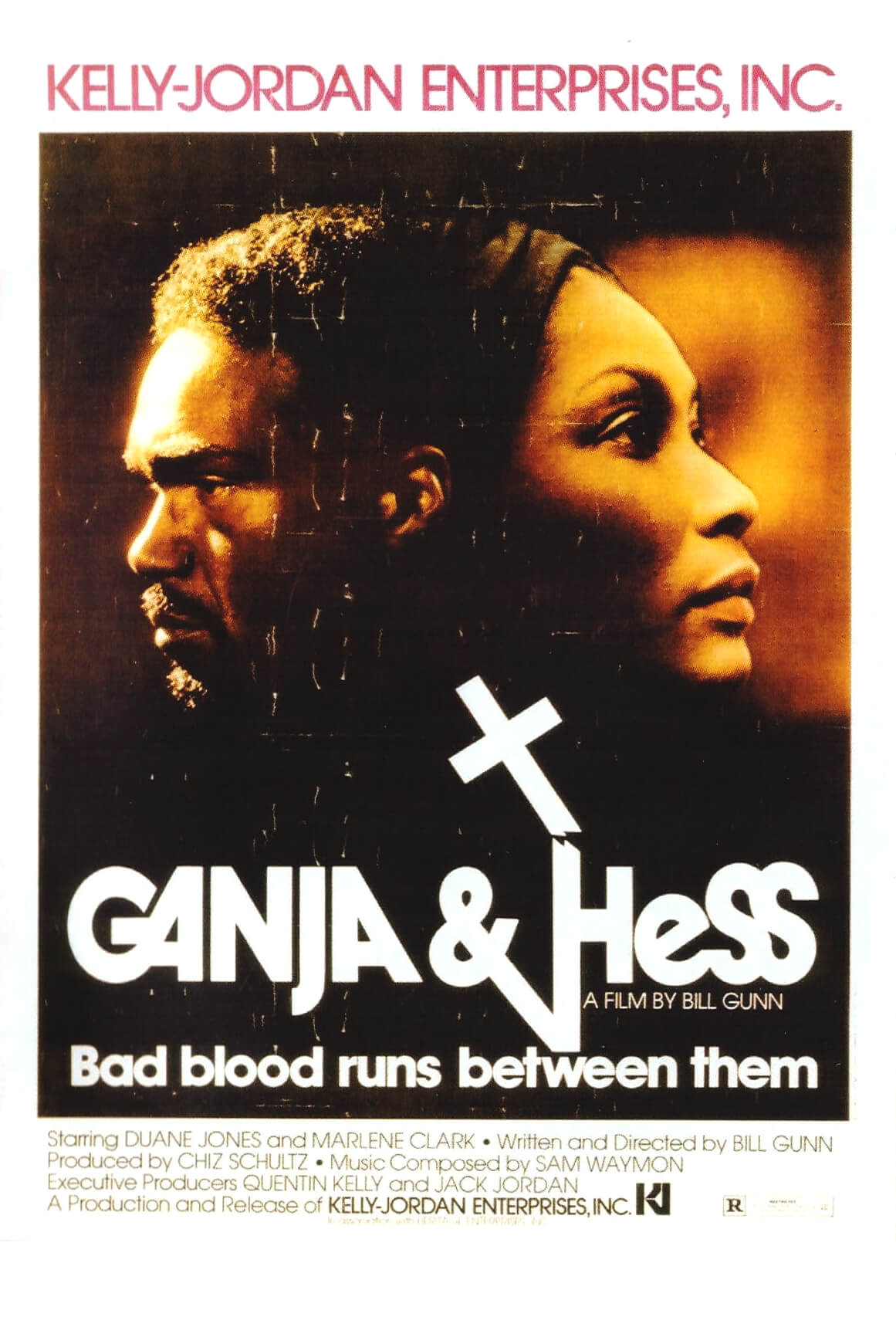

This notion of seeing and acknowledging that which is right in front of you, even though it is often ignored by others due to issues of social hierarchies determined by colonial power and race, becomes an essential component of Denis’ cinema. It is Denis’ “vagabond” quality, observed by scholar Judith Mayne, that lends her the perspective of an outsider capable of looking and assessing the dynamics of a situation. That view served her curiosity and helped ensure her acceptance into France’s premier film school, Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC), where she studied in the late 1960s around the time French filmmakers rebelled against the “Tradition of Quality” that dominated the French film industry, resulting in the New Wave movement whose progenitors rethought traditional modes of cinema. While studying at the IDHEC, Denis met her idol Jacques Rivette, for whom she later served as assistant director. After graduating in 1971, Denis worked for more than a decade alongside filmmakers such as Dusan Makavejev, Costa-Gavras, Jim Jarmusch, and Wim Wenders. Each new collaboration enriched her desire to direct her own projects and, while serving as first assistant director on Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), she completed a script for Chocolat, her debut. But as she would later claim, these early collaborations taught her more about financing and distribution than the craft of filmmaking, which she had already learned at IDHEC. She credits her mentors with teaching her how to achieve a clarity of vision and purpose that comes with the most distinguished filmmakers.

This notion of seeing and acknowledging that which is right in front of you, even though it is often ignored by others due to issues of social hierarchies determined by colonial power and race, becomes an essential component of Denis’ cinema. It is Denis’ “vagabond” quality, observed by scholar Judith Mayne, that lends her the perspective of an outsider capable of looking and assessing the dynamics of a situation. That view served her curiosity and helped ensure her acceptance into France’s premier film school, Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC), where she studied in the late 1960s around the time French filmmakers rebelled against the “Tradition of Quality” that dominated the French film industry, resulting in the New Wave movement whose progenitors rethought traditional modes of cinema. While studying at the IDHEC, Denis met her idol Jacques Rivette, for whom she later served as assistant director. After graduating in 1971, Denis worked for more than a decade alongside filmmakers such as Dusan Makavejev, Costa-Gavras, Jim Jarmusch, and Wim Wenders. Each new collaboration enriched her desire to direct her own projects and, while serving as first assistant director on Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), she completed a script for Chocolat, her debut. But as she would later claim, these early collaborations taught her more about financing and distribution than the craft of filmmaking, which she had already learned at IDHEC. She credits her mentors with teaching her how to achieve a clarity of vision and purpose that comes with the most distinguished filmmakers.

After more than a dozen narrative features, several documentaries, and a few shorts, Denis’ identity as a filmmaker remains constant. To watch a Claire Denis film is to engage on every level in the images and their meaning as they unfold before you. Their very fabric is an intractable intertextuality of substance and aesthetics. Thematically, she is concerned with the things that have been pushed to the periphery; she asks why they’re there. Given her upbringing and background with filmmakers who are similarly concerned with identity and difference within a distinct formal approach, it was perhaps inevitable that Denis collaborated on White Material with the French author and playwright Marie NDiaye, whose Senegalese father left their family when she was just one year old. When they started to collaborate on the film, both had explored questions of postcolonial identity and cultural dynamics through oblique narratives, complex characterizations, and powerful visual imagery, be it cinematic or literary. Both have an edge in their approach to fiction, regardless of the format. Take NDiaye’s novel Trois femmes puissantes (Three Strong Women), released the same year as White Material in 2009. It featured a trio of thinly connected stories about the troubled relationships between characters from France and Senegal. Similarly to Denis’ aesthetics on film, NDiaye is concerned with experience and heightened descriptions of raw moments. Both women use the subjectivity of their characters as a way for the viewer to read or inhabit an alternative perspective, which in turn reflects the dynamics of colonialism and power.

The structure of White Material is elliptical and by extension demands that the viewer consider how things descended into horror—much in the same way that film noirs often begin with a scene of the protagonist dying, only to go back and consider how the character got there. However, Denis’ use of structure is less conventional, almost nebulous, and avoids the familiar bookend device. The film opens with a dreamlike, overlapping series of images of yellow dogs running through fields of Arabica bushes. Throughout, the yellow dog symbolizes the presence of white European colonists, the former ruling class that still clings to their notions of imperialist rule, although now they scavenge a postcolonial territory that does not belong to them. We then see frantic images of African soldiers pointing flashlights in a dark home, searching for a rebel leader known as The Boxer (Isaach de Bankolé, a regular in Denis’ films since Chocolat). ”He’s dead all right,” they announce when they find his corpse. A moment later, those same African soldiers close the doors on a white man, distinguishable only by his bald head and back tattoo, locking him inside a fiery warehouse where he will burn to death. After this series of dizzying and uncertain images, Denis settles in the past, where Maria Vial, donning her pink dress and makeup, waves down a bus. During her desperate ride home, she reflects on the events that led to this moment, her face gaunt, her expression somehow both detached and concerned. In this way, White Material exists in a series of flashbacks and fragmented glimpses in time that one should resist calling flashbacks-within-flashbacks; instead, the narrative structure amounts to a poetic deconstruction of an event.

Going further back, Maria attempts to maintain the Vial’s coffee plantation, though it’s owned by her former father-in-law (Michel Subor) and managed by her ex-husband André (Christopher Lambert), with whom she has an adult son, Manuel (Nicolas Duvauchelle), a maladjusted layabout. It’s no coincidence that Denis has set the events on a coffee plantation, as coffee was a central cash crop of colonial exploitation, as well as the slave trade in Africa. Only in the postcolonial era, where coffee producers often demand a “fair trade” label, has coffee transformed from a colonialist device into one of capitalist neo-imperialism. Chocolat also took place on a coffee plantation, although the setting of Denis’ first film and White Material feel decades apart. Whereas Chocolat took place in a specific historical context, namely Cameroon at the end of French colonialism in the mid-twentieth century, the latter film embraces an almost allegorical evasion of time and place. It seems closer to today given the presence of a rebel radio announcer who plays political reggae and preaches to young militants that the age of “white material” has ended, referencing the objects owned and valued by white people born into luxury. “They’re running scared,” says the voice on the radio, “their suitcases stuffed with booty they amassed while you starved.”

Going further back, Maria attempts to maintain the Vial’s coffee plantation, though it’s owned by her former father-in-law (Michel Subor) and managed by her ex-husband André (Christopher Lambert), with whom she has an adult son, Manuel (Nicolas Duvauchelle), a maladjusted layabout. It’s no coincidence that Denis has set the events on a coffee plantation, as coffee was a central cash crop of colonial exploitation, as well as the slave trade in Africa. Only in the postcolonial era, where coffee producers often demand a “fair trade” label, has coffee transformed from a colonialist device into one of capitalist neo-imperialism. Chocolat also took place on a coffee plantation, although the setting of Denis’ first film and White Material feel decades apart. Whereas Chocolat took place in a specific historical context, namely Cameroon at the end of French colonialism in the mid-twentieth century, the latter film embraces an almost allegorical evasion of time and place. It seems closer to today given the presence of a rebel radio announcer who plays political reggae and preaches to young militants that the age of “white material” has ended, referencing the objects owned and valued by white people born into luxury. “They’re running scared,” says the voice on the radio, “their suitcases stuffed with booty they amassed while you starved.”

The voice on the radio frames the conflict, wherein, reading the signs of rebellion, the French colonizers in an unnamed African country have abandoned their stations. Rebel factions of militants are sweeping the countryside, and soldiers of the African army have struggled to contain them. The rebel leader, The Boxer, has been wounded, but his influence has been such that he’s inspired his followers to take action. We see droves of mostly children armed with guns and machetes, and one adult among them carries a small child on his shoulders and an RPG in his hands. The children who aren’t part of the rebellion have stopped showing up to school. Amid the chaos early in the film, a French army helicopter flies over the Vial plantation, warning Maria to give up her coffee plantation and leave the area because their forces are withdrawing. When she refuses, they drop a few survival kits and flee. Maria somehow ignores these countless warning signs and remains determined to cultivate the plantation’s latest harvest. Her workers take to their bikes to abandon the plantation, though she pleads with them to stay another five days, despite their observation of “Suffering and war everywhere!” Even this is not a deterrent for Maria. She resolves to go into town to hire more workers, at which point she discovers the plantation’s gate attendant has abandoned his post, another grim sign in a film brimming with them.

Huppert embodies the wiry, frenetic energy of Maria to such an extent that her performance drives White Material’s flow of narrative violence and action. Huppert, no stranger to intense performances that assault both her character and the spectator, sought a collaboration with Denis when she suggested the director adapt The Grass Is Singing, Doris Lessing’s 1950 novel that negotiates a similar relationship to the one Denis explored in Chocolat—between a European woman and an African man, and the role that social enslavement plays in that exchange. But Huppert and Denis explore something less understated and more visceral than Lessing’s novel, making the most of the performer’s radiant energy and intensity, while also allowing her character to inhabit the realm of the unknowable. Huppert’s performance is augmented by Stuart Staples’ agitated score, and Yves Cape’s volatile cinematography that employs handheld cameras with really-there immediacy and impressionistic transitions between shots, capturing Maria’s state of mind. But in other scenes, Cape and Denis show Maria resting after a frenzied day, eating a bowl of rice outside in silence. How could anyone be so calm under these conditions? Why does Maria stay on the plantation? Does she feel a misplaced sense of ownership over the land? Is it pride for the work she’s already put into the crop? Is her colonial ideology of white superiority so ingrained that she feels untouchable against a black threat?

Although most of the writing about White Material centers on Huppert’s character and Denis’ exploring questions of postcolonial identity and race, the character of Maria’s son, Manuel, also presents a compelling illustration of these themes, but to greater extremity. Maria’s unchecked ferocity is mirrored by the gradual degradation of her adult son, a product of privilege and arrested development who is an extension and concentration of her mania. Manuel, who was born in Africa, loafs around in bed with an aversion to the work that his mother puts into the plantation. As he lazily prepares for the day by jumping into a swimming pool, two young rebels emerge from the bushes, one armed with a machete, the other with a spear. They snoop around the house, stealing some of Maria’s jewelry, clothing, and a gun. Manuel chases after them, only to be held at gunpoint and forced to his knees. At the moment the boys force him to remove his shirt, the audience sees his back tattoo and realizes he is the same white man closed in the burning warehouse in the opening. Things are going to get much worse. The incident has shaken Manuel, and he seems to crack: He disappears for a time, grabs a rifle, and shaves his head. He radicalizes and curiously identifies with the rebels, shoving his blond hair, which is “bad luck,” into the mouth of a servant. In essence, he becomes a yellow dog, although he is rabid. “This is his country. He was born here,” says Chérif (William Nadylam), the local mayor, to Maria. “But it doesn’t like him.” Unwanted in his own country and removed from that of his parents, Manuel belongs nowhere. And we cannot help but suspect him when his father ends up dead. Perhaps he came to blame André for his displacement while maintaining a delusion that he is one of the rebel boys.

Although most of the writing about White Material centers on Huppert’s character and Denis’ exploring questions of postcolonial identity and race, the character of Maria’s son, Manuel, also presents a compelling illustration of these themes, but to greater extremity. Maria’s unchecked ferocity is mirrored by the gradual degradation of her adult son, a product of privilege and arrested development who is an extension and concentration of her mania. Manuel, who was born in Africa, loafs around in bed with an aversion to the work that his mother puts into the plantation. As he lazily prepares for the day by jumping into a swimming pool, two young rebels emerge from the bushes, one armed with a machete, the other with a spear. They snoop around the house, stealing some of Maria’s jewelry, clothing, and a gun. Manuel chases after them, only to be held at gunpoint and forced to his knees. At the moment the boys force him to remove his shirt, the audience sees his back tattoo and realizes he is the same white man closed in the burning warehouse in the opening. Things are going to get much worse. The incident has shaken Manuel, and he seems to crack: He disappears for a time, grabs a rifle, and shaves his head. He radicalizes and curiously identifies with the rebels, shoving his blond hair, which is “bad luck,” into the mouth of a servant. In essence, he becomes a yellow dog, although he is rabid. “This is his country. He was born here,” says Chérif (William Nadylam), the local mayor, to Maria. “But it doesn’t like him.” Unwanted in his own country and removed from that of his parents, Manuel belongs nowhere. And we cannot help but suspect him when his father ends up dead. Perhaps he came to blame André for his displacement while maintaining a delusion that he is one of the rebel boys.

Maria’s digression is similar to that of Manuel; however, her landslide covers the entire arc of the film, and her behavior is less radical than Manuel’s drift into mania, at least until the horrifying conclusion. Her decline is portrayed in a series of denials and refusals to acknowledge that the country’s civil war will soon sweep over the Vial plantation. When someone has clearly penetrated their fence, she chooses to believe it was a young shepherd stealing livestock; even after a bullet shell is located nearby, she ignores the warning sign. When the power goes out, she resolves to turn on the generator, which uses up precious gas they will need, should they choose to escape—but escape has never crossed her mind. When the head of a ram topples out from inside a basket of Arabica berries, placed there as a threat by either rebels or the plantation’s workers, she tries to bury it and hide the evidence. But André quickly finds it. “Do you have any idea what this means?” he shouts. “We’ll all die!” People keep telling her, “You don’t get it,” but her sense of ownership over the land is unshakable and blinding. “I have nowhere to go. I won’t give this up,” she declares unwaveringly. Dispossessed and desperate to carve out a home, Maria cannot and will not see the situation as it unravels around her.

In an interview with Jean-Luc Nancy, Denis called the experience of having black servants in a French colonial household in Cameroon “abnormal,” but then she has also told interviewers of how her family felt no more at home in France, where the national identity was shifting after the collapse of the empire. In White Material, Denis shows us a character without the capacity for the perspective that she had as a child. Maria sees herself as part of the land she owns, which of course she does not own in any way; rather, she facilitates it under the ownership of her father-in-law, whereas the notion that she, as a colonizer, doesn’t belong there seems far removed from her mind. Not all scholars agree. James S. Williams writes in his article “Beyond the Other: Grafting Relations in the Films of Claire Denis” that the film is a “case study of female obsession and hysteria,” a Lacanian psychoanalytic interpretation that threatens to downplay the postcolonial texts evident throughout the film. But Denis seems less interested in female identity—which is otherwise a frequent concern of her work—than the question of how white people continue to treat people of color around the world. History tells us that slavery is over, that colonialism has ended, and someone like Maria believes in that to the extent that she is blind to how they still exist in less obvious forms. She persists on the belief that she belongs in Africa, that it is her home. In a sense, she is unconscious of her own whiteness as it relates to the people around her. She has taken that whiteness for granted to such as an extent that, when Chérif points out that her blond hair and white material are unwanted in their country, it is a shock to her.

White Material’s nonlinear structure implants the knowledge of what the African locals, and indeed everyone besides Maria and Manuel, seem to already know: the situation is doomed. Denis places that appropriate sense of dread and urgency in the viewer, which makes Maria’s behavior seem all the more unhinged and somehow even tragic, even though the film is no tragedy. Still, her behavior demonstrates that she maintains an ideological superiority toward Africans, whom she views as subhuman out of sheer blindness and self-absorption, as evidenced in a sequence in which she hires some cheap workers for the plantation to replace those who abandoned it. The workers cram into the bed of her truck and, after they’re loaded, she drives them to a local school and asks them to wait as she picks up José, her ex-husband’s son. The workers must stand in the back of the truck like human cargo, waiting in the sun as the white woman conducts her chore, and the image reveals Maria’s persistent inclination toward ideological enslavement. Worse, her treatment of the workers turns out to be unnecessary, as André, too, has arrived to pick up José from school. For Denis, who grew up with an outsiders appreciation of the racial and cultural dynamics of colonialism, a character like Maria must seem dangerously, cruelly oblivious.

White Material’s nonlinear structure implants the knowledge of what the African locals, and indeed everyone besides Maria and Manuel, seem to already know: the situation is doomed. Denis places that appropriate sense of dread and urgency in the viewer, which makes Maria’s behavior seem all the more unhinged and somehow even tragic, even though the film is no tragedy. Still, her behavior demonstrates that she maintains an ideological superiority toward Africans, whom she views as subhuman out of sheer blindness and self-absorption, as evidenced in a sequence in which she hires some cheap workers for the plantation to replace those who abandoned it. The workers cram into the bed of her truck and, after they’re loaded, she drives them to a local school and asks them to wait as she picks up José, her ex-husband’s son. The workers must stand in the back of the truck like human cargo, waiting in the sun as the white woman conducts her chore, and the image reveals Maria’s persistent inclination toward ideological enslavement. Worse, her treatment of the workers turns out to be unnecessary, as André, too, has arrived to pick up José from school. For Denis, who grew up with an outsiders appreciation of the racial and cultural dynamics of colonialism, a character like Maria must seem dangerously, cruelly oblivious.

It takes violence against her family, if not the total destruction of the plantation by the African army, to shake Maria out of her perspective, delusions, and denials. The second round of workers demands to be returned to the village nearby after learning that The Boxer hides on the Vial plantation, dying from a gunshot wound. In another display of her willful ignorance of the political situation occurring around her, Maria agrees to shelter The Boxer, refusing to consider the consequences should he be discovered. When she sees the violent consequences of the civil war upon returning the workers to the village, she frantically returns to the farm, which, by the time she arrives home, the army has burned. She finds the body of her son, now charred black, as he seemed determined to become. And much as Manuel had done when stripped of his identity, Maria resorts to murder when robbed of the farm and motherhood that defined her. She kills the only one left alive by the soldiers, her father-in-law, whom she holds responsible for Manuel’s death—but perhaps more so for betraying a promise that the plantation would be hers, and signing a contract that hands the plantation over to Chérif.

In the end, White Material is a portrait of the horror that results from an entrenched ideology. Perspectives that refuse to acknowledge or see outside of the demarcated limits of national borders, skin color, or imperialist power leave themselves open to a rude awakening when confronted by the reality that these are illusions. Huppert’s severe performance embodies the fixed mindset of a person who cannot see herself or her own position within her surroundings clearly. In a sense, Denis’ film is about a defect in perspective, and further, the importance of seeing beyond one’s immediate social or cultural limitations. More specifically, it is about the isolating and displacing effect of colonialism that robs one of their identity, making Maria a character misplaced between two worlds, unable to return to her homeland in France, unwanted in Africa. The nonlinear structure and elusory visual state in which Denis portrays this condition perfectly echo the filmmaker’s own identity as a worldly figure unbound by a narrow ideology of race or nationalism, and the amorphous identity of Maria. It is this perspective that informs Denis’ uncommon use of form to force her viewer to see, investigate, and engage with the areas of the world that might otherwise go unseen.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, David!)

Bibliography:

Beugnet, Martine. Claire Denis (French Film Directors). Manchester University Press, 2004.

Mayne, Judith. Claire Denis. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Vecchio, Marjorie, editor. The Films of Claire Denis: Intimacy on the Border. I.B. Tauris, 2014.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review