The Definitives

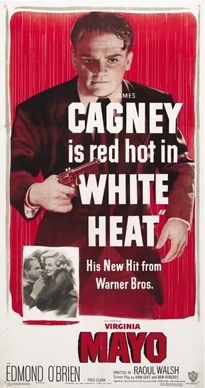

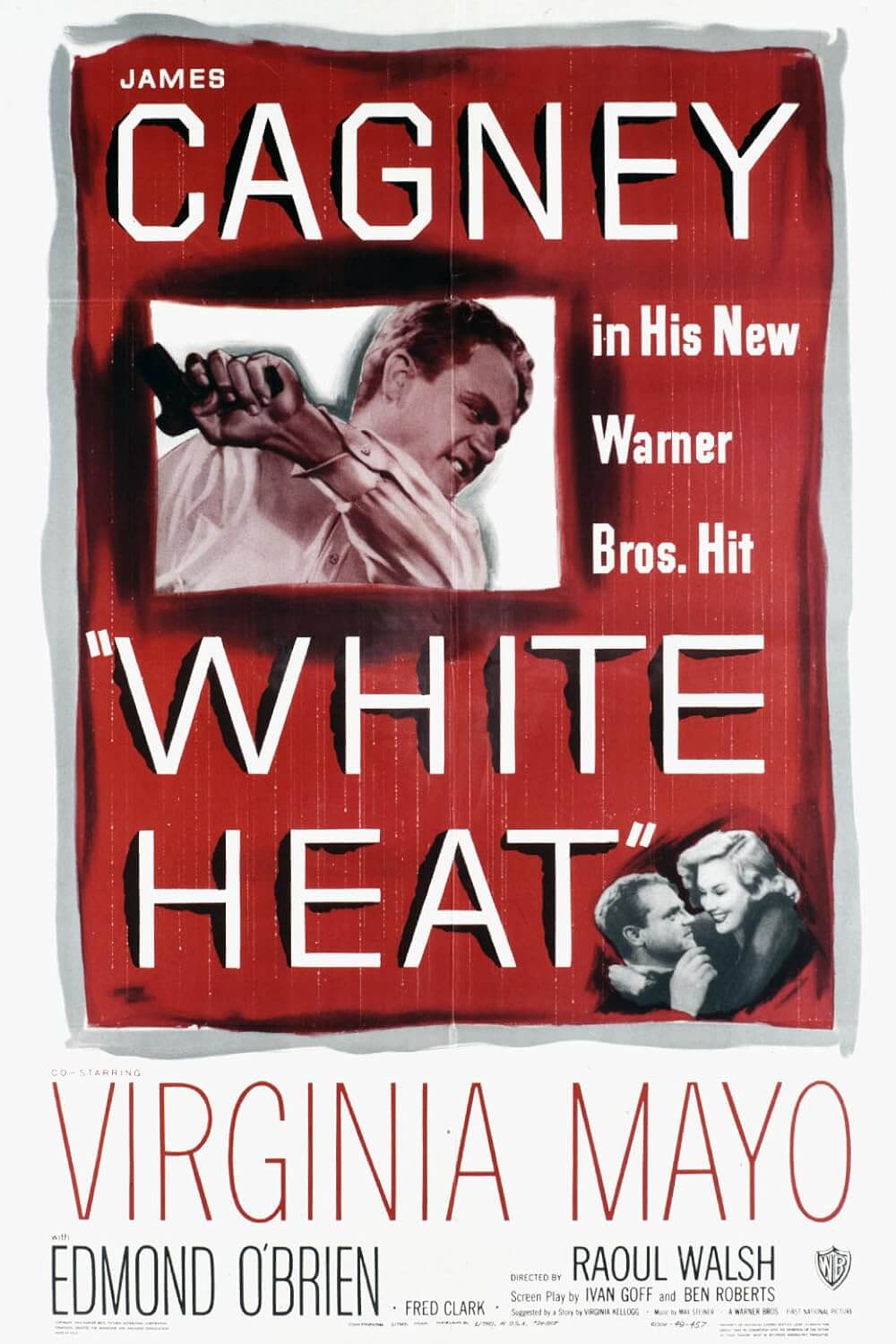

White Heat (1949)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

James Cagney reinvented his longstanding gangster persona in White Heat, the 1949 film in which he plays Cody Jarrett, a wanted criminal whose unlawful activities are reflected by the character’s extreme inner madness. Directed by Raoul Walsh, the picture proved ahead of its time by gravitating around the psychological makeup and often shocking reality of Cagney’s role. During the 1930s, Cagney had starred in a number of classic gangster pictures for Warner Bros., the studio most associated with screen gangsters, and almost none of these films considered the criminal beyond their unhinged social conscience and the freedom of gangster violence. Even more than other screen gangsters such as Edward G. Robinson or Humphrey Bogart, Cagney’s name would be forever linked with the motion picture gangster, no matter how hard he tried to shed that image with serious dramas, musicals, or comedies. Despite this, Cagney returned after a decade-long effort to distance himself from the violence and amorality associated with gangster roles, recognizing White Heat was something far more than another studio genre piece. Through his vicious, psychopathic, yet strangely sympathetic turn as Cody Jarrett, the actor’s legendary presence gives way to a film that both sums up and sends off his Cagney’s history in the classic Warner Bros. gangster picture.

To understand how Cagney reinvented himself and amalgamated his previous gangster roles with this film, one must first appreciate the actor’s long and rocky history with the studio. Of the major Golden Age studios known as the Big Five, Warner Bros. industrialized the movie business to a scale far beyond its competition. Even their logo presents a factory-like personality; other studios displayed aggrandizing and majestic imagery, such as Columbia’s pseudo-Statue of Liberty figure or Paramount’s mountain reaching to the heavens. But the Warner Bros. logo resembles a stamp imprinted onto a film’s opening as if embossed by a machine press. It was a seal of craftsmanship denoting individuality, pride, uniqueness, and, most importantly in their post-Depression-era market, their business-savvy approach. Indeed, Warner Bros. supplied an advantage over other studios by the transcendent quality of their talent and work. In its heyday, the studio boasted the most imposing assemblage of contracted stars, directors, and background players in all of Hollywood. Names like Humphrey Bogart, Bette Davis, Katherine Hepburn, George Raft, Olivia de Havilland, and Paul Muni—not to mention an additional roster of Looney Tunes, including Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck—were all at the studio’s disposal. Good for the studio, bad for the talent that was sometimes forced into taking an unwanted job. And if they complained, the studio heads issued fines or suspensions as penalties.

As a result, the Warners gained a reputation for being penny pinchers, furthering their factory-like standing. Certainly, they were not as wasteful as today’s opulent movie business. But Jack and Harry Warner reportedly picked up nails around the lot to save from wasting then-precious iron, otherwise consumed by the army for wartime uses. Respected contract players like Errol Flynn considered the studio lot “a country club” during its prime, but minor underlings or stars with a string of box-office bombs believed the place worse than Alcatraz, with Jack Warner monitoring the onset activity of his employees and making sure they remain on the property between the business hours of 9 am to 5 pm, six days a week. So while the productive studio system had Warner Bros. processing nearly 50 pictures a year, the consequences of The Golden Age upheld a flawed methodology. For Cagney, the actor’s string of early career tough-guy roles had made him famous in Hollywood. But being a trained stage actor, dancer, and vaudevillian performer by trade, he wanted more out of his celebrity than typecast roles. Yet, his studio contract left him with no control and obligated to sometimes upwards of four pictures a year.

In addition to penny-pinching, Warner Bros. was also renowned for its “hard-hitting” appeal. They were Hollywood’s most violent studio, embracing the gangster genre with gritty pictures like The Public Enemy (1931) and Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), both starring Cagney. Often criticized for glorifying violence and depicting the murderous acts of unscrupulous hoodlums, the studio nonetheless made a fortune on the genre. Of course, they also released polished prestige pictures, screwball comedies, musicals, and romances, just like their competition. But taboo subjects were welcomed and practiced, including their passionate anti-Nazism, even when the United States government maintained an isolationist stance. Jack Warner, the youngest of the four Warner brothers, backed pictures like 1939’s Confessions of a Nazi Spy, starring Edward G. Robinson as an FBI agent exposing undercover Nazi operatives in the U.S., and received death threats for his efforts, while his brother Harry defended the studio against Washington’s accusations of warmongering. As for Cagney, he starred in more than a dozen gangster pictures for the Warners, but his evident commoditization and subjugation under the studio system left him wanting out of his contract and into more diverse roles.

Cagney’s first role for Warner Bros. was Sinners’ Holiday (1930), a crime drama based on the play Penny Arcade, a show in which Cagney originally starred. The studio bought the rights and quickly signed Cagney to a contract, which was extended, and extended again. His breakthrough role was in The Public Enemy as crook Tom Powers, who famously smashes a grapefruit into Mae Clark’s face, and it firmly established Cagney’s hard-edged screen persona. Meanwhile, over the years, the Warners breached their contract with Cagney on several occasions. Finally, Cagney sued and left Warner Bros. in 1935 to become an independent actor, only to return in 1938 because business was better under a major studio. After winning his Oscar for Best Actor on Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), he departed the studio once again and launched his own production company, Cagney Productions, at United Artists, with his brother, William Cagney. After a few creative and commercial duds, Cagney returned to Warners once more in 1949 for White Heat, a picture that would revive memories of Cagney from the early gangster pictures of the 1930s.

After his last gangster picture in 1939, The Roaring Twenties, Cagney had actively avoided any connection with the genre to prevent being further typecast as the hard-boiled criminal with a Tommy gun, even if Yankee Doodle Dandy alone accomplished that feat. Although he would later admit to taking the role of Cody Jarrett for “a five-letter word beginning with m and ending y,” the actor overlooked his early career disputes with the Warners for a chance to create a gangster characterization unlike that of any criminal seen in cinemas before. For White Heat, Cagney reteamed with director Raoul Walsh, who had previously directed him in The Roaring Twenties and The Strawberry Blonde (1941). Like Michael Curtiz (The Adventures of Robin Hood and Casablanca), Walsh was a studio craftsman, his experience spanning a range of genres. For the Warners, Walsh brought much personality and style to a string of Errol Flynn vehicles, but he specialized in gritty crime dramas featuring vulgar characters—none so much so as Cody Jarrett. To celebrate the reunion of Warner Bros. and James Cagney, the studio’s publicity team issued a huge press release announcing Cagney’s return “home” to the studio, “To the type of bing-bang melodrama that made him a top star in his earliest years.” Despite the studio’s enthusiasm, Cagney remained soured toward the Warners, Jack Warner in particular, for allowing only a limited shooting schedule and reinforcing harsh budgetary restrictions on the picture, regardless of the eventual success and acclaim of White Heat.

A train robbery of U.S. Treasury cash opens the film, introducing Cody Jarrett as he kills unarmed witnesses—locomotive operators who must die because they hear Cody’s name mentioned by one of the other robbers. Within moments, the audience views Cody as a ruthless, unrepentant killer who enjoys criminality; yet, unlike Cagney’s earlier gangster performances, what later becomes Cody’s marked insanity adds layers to the role. After the robbery, Cody and his gang hide out together in a small log cabin until the heat from the authorities cools down. Inside this enclosed space are Cody, a number of Cody’s goons, his wife Verna (Virginia Mayo), and his mother, Ma Jarrett (Margaret Wycherly). Dismissive toward Verna and ever-affectionate toward his strong-willed mother, Cody suffers from unbearable headaches that put him into a frenzy. In the cabin, one attack sends him into the next room where only Ma Jarrett can help him recover. She rubs his head and neck, and afterward, Cody sits on this mother’s lap—a push-the-envelope detail Cagney improvised. Ma, a calculating criminal mentor, instructs Cody not to let the others see him in such a rattled state. She brings him a drink to calm him down, and she gives her customary salute: “Top of the world, son”—setting high expectations no deranged son could ever hope to meet. With this, we now see the unrepentant killer as a maddened mama’s boy.

Screenwriters Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts based some of White Heat on the real-life Ma Barker (1873-1935), a much-publicized gang leader, or at least complicit bystander, whose offspring committed a series of robberies and kidnappings in the early 1930s. Margaret Wycherly, a former classical actress, plays Ma Jarrett with ice water in her veins. She’s a straight-lipped, cold-hearted figure—a character far removed from the era’s typical good-hearted mother and, therefore, an outrageous representation of the period. As the sole adviser to the king, she jealously protects her son, forcing us to wonder how Cody ever had the occasion to fall in love with Verna. Cody’s almost boyish behavior, such as the way Cagney bites his lower lip like a child, presents a psychopathic character obsessed with his mother, nearly to the extent of Norman Bates in Psycho (1960). A passing remark later suggests that, as a boy, Cody would pretend to have headaches to gain his mother’s attention. As an adult, Cody’s desperate need for Ma Jarrett’s love has translated into a psychosomatic reality, tearing away at his brain. As a result of this complex, Cagney’s childlike performance never becomes unintentionally humorous or disturbing to an extreme that prevents us from enjoying Cagney’s screen presence; nor does Walsh emphasize the character’s Freudian traits as oddities. Rather, Cody’s affection toward Ma Jarrett is sincere, tragic, and one of the many fascinating intricacies about the character.

Screenwriters Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts based some of White Heat on the real-life Ma Barker (1873-1935), a much-publicized gang leader, or at least complicit bystander, whose offspring committed a series of robberies and kidnappings in the early 1930s. Margaret Wycherly, a former classical actress, plays Ma Jarrett with ice water in her veins. She’s a straight-lipped, cold-hearted figure—a character far removed from the era’s typical good-hearted mother and, therefore, an outrageous representation of the period. As the sole adviser to the king, she jealously protects her son, forcing us to wonder how Cody ever had the occasion to fall in love with Verna. Cody’s almost boyish behavior, such as the way Cagney bites his lower lip like a child, presents a psychopathic character obsessed with his mother, nearly to the extent of Norman Bates in Psycho (1960). A passing remark later suggests that, as a boy, Cody would pretend to have headaches to gain his mother’s attention. As an adult, Cody’s desperate need for Ma Jarrett’s love has translated into a psychosomatic reality, tearing away at his brain. As a result of this complex, Cagney’s childlike performance never becomes unintentionally humorous or disturbing to an extreme that prevents us from enjoying Cagney’s screen presence; nor does Walsh emphasize the character’s Freudian traits as oddities. Rather, Cody’s affection toward Ma Jarrett is sincere, tragic, and one of the many fascinating intricacies about the character.

Though cited as a pure gangster film, White Heat contains qualities of a film noir as well. Cody represents the noir’s doomed antihero, while Verna is a classic femme fatale in the noir style. When Cody decides it’s safe to leave their cold mountain hideout, there’s only one blanket for the car ride. Cody takes the covering from Verna and puts it down on Ma’s lap. His loyalties are obvious, but then the duplicitous Verna doesn’t command our sympathies either. Walsh introduces Verna lying on a bed, snoring through her nose and mouth. What an entrance, as unpolished and unadorned as anyone is likely to see from Golden Age cinema. Mayo seems to relish the bawdy, voluptuous, juicy role; her Verna is a vulgar, unredeemable sort who does anything to survive and has almost no scruples. Besides snoring, Walsh shows her spitting out her gum without a hint of modesty before she kisses her husband; such baseness would never appear in a Production Code gangster picture in the 1930s. A key subplot involves Verna shacking up with Cody’s underling, Big Ed (Steve Cochran), once Cody turns himself in—not for the train robbery, but for a lesser crime with a smaller sentence. While Cody serves two years, Verna beds Big Ed on the outside and schemes to take over Cody’s gang. She and Big Ed plot to rid themselves of Ma Jarrett—the only gang member loyal to their former leader.

Once Cody lands himself in prison by his own esteem, the U.S. Treasury arranges for undercover agent Hank Fallon (Edmond O’Brien) to share Cody’s cell and determine the identity of Cody’s fence. Walsh shifts the film from Cody’s perspective to Fallon’s, forcing the viewer to look more objectively at Cody’s criminality and, ultimately, his madness. Fallon’s mission to earn Cody’s trust proves a slow process until Big Ed makes the mistake of hiring convict Roy Parker (Paul Guilfoyle) to kill Cody inside—Fallon foils the attempt and gains the trust of Cody, becoming a brother figure. When Ma visits to check on her boy, she learns of the attempt on Cody’s life and vows, against her son’s warnings, to take care of Big Ed herself. The bond between Cody and Fallon is strengthened even further when Cody learns Ma was killed by none other than Big Ed. The scene, one of the greatest in all of cinema, reveals the extent of Cody’s psychosis and the bursting talent of Cagney. The scene takes place in the mess hall during a meal, a massive setting populated by hundreds of extras. Walsh fought with Warner Bros. to shoot the sequence in the mess hall; they wanted a cheaper setup filmed in the chapel. But Walsh recognized that what unfolds next would need witnesses—all of them silenced by Cody’s reaction and Cagney’s incredible performance.

In the scene, Cody passes a message down through inmates like a game of telephone, Walsh’s camera following as each con relays, “Ask about Cody’s mother.” When the audiece hears the response—“She’s dead”—we watch with horror as the convicts pass the message back. Knowing what an affect it will have on Cody, we watch the fuse burn, inching closer to the moment when the bomb goes off. The last prisoner hesitates and then tells Cody the news. Walsh planned the reaction ahead of time with Cagney, and they kept his response a secret from the more than 300 extras populating the hall. A low moan begins to build inside the actor until he detonates into a screaming display that shocked everyone on set, which is evident in their genuinely stunned expressions. Cody climbs onto the table, propelled by unrestrained emotion and collapses onto the meals of his fellow convicts, and then onto the floor as he releases a jarring cry, biting his lower lip like a child lost in a tantrum. Cody’s fit propels him into the prison guards, several of whom he takes down with a single punch, until finally, the guards gain control and carry him out of the room as he howls, “I want to get out of here!” in a barely intelligible wail.

Cagney has credited two sources of inspiration for the prison breakdown scene: The actor recalled visiting an asylum on Ward’s Island when he was a boy and replicated “the shrieks, the screams of those people under restraint.”He also recreated the sounds his father would make during a bout of drunkenness—the kind of twisting, inebriated moan we hear when Cody first learns the news. Until this moment in White Heat, Cody’s family history of psychosis is only hinted at and talked about by others, such as when Cody is overcome by a headache at the mountain hideout. “He’s nuts,” says one of his goons. “Just like his old man.” Another remark Cody makes later reveals his father died “kicking and screaming” in an institution. Allusions aside, the audience is never really informed in technical terminology about what’s wrong with Cody Jarrett. After his breakdown, Fallon learns the prison doctors plan to have Cody committed to an asylum, and the prognosis is left to our imagination. But perhaps defining his affliction would create a distance between Cody and the audience, who might see him as a mere head case if diagnosed. Fortunately, his mental ailments are left a mystery, and the character remains more compelling for it. Moreover, Cody is not oblivious to his own condition. After he arranges a daring prison escape and brings along Fallon, who will ostensibly become Cody’s sole family member, he confesses to Fallon that he’s started talking to Ma when no one’s around. “It’s a good feeling,” he says, then pauses. “Maybe I am nuts.”

Cody’s awareness of his own psychological volatility transforms the character from an unsympathetic criminal into a tragic figure, more so because the burden paints him as a boy incapable of letting go of his attachment to his mother. White Heat so effectively bonds us to Cody’s emotional makeup—and yet, amazingly, does this without romanticizing his criminality—that the audience feels a sense of antagonism about Fallon and a strange sympathy toward Cody, complete with an elated, if tragic, impression of Cody’s end. The picture’s famous climax sends Cody out with an unparalleled bang. By this time, Cody has avenged his mother by killing Big Ed, formed a new gang, and plotted a new score to rob a chemical plant by hiding inside a “Trojan Horse” gas truck. Fallon, having met Cody’s fence known as “The Trader” (Fred Clark), arranges a raid at the plant to finally take down Cody Jarrett. As the police race to corner Cody’s men, the getaway driver Creel (Ian MacDonald) recognizes Fallon as the undercover cop who pinched him years ago and exposes Fallon to Cody. Now without a mother or a surrogate brother, Cody is alone, and the betrayal sends him spiraling into a madness from which he will not recover. In the resulting shootout, Cody climbs atop a tall spherical gas storage tank tower. Fallon lands several shots with a rifle, but Cody, in all his crazed glory, refuses to go down. Instead, he fires into a tank, sending up blazing spires around him. “Made it, Ma! Top of the world!” he shouts, just before the tank explodes.

Fallon’s last lines—“He finally got to the top of the world. And it blew right up in his face”—end the picture, but they fail to instill the moral center of Cagney’s other gangster pictures as then required by the Production Code. White Heat contains little or no overriding moral lesson about the state of criminality in America, whereas Cagney’s previous genre efforts often included a line such as “I ain’t so tough” uttered by Cagney’s bullet-riddled Tom Powers in The Public Enemy, or in The Roaring Twenties when Gladys George’s Panama Smith cradles the dead body of Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett and announces, “He used to be a big shot.” Both instances demonstrate where a life of crime gets you, and both films are prefaced by a virtual public service announcement condemning the criminal acts portrayed within the film. But Cody Jarrett’s detonation teaches the audience nothing, nor does White Heat attempt to explain away Cody’s everlasting love of criminality. Refreshingly, the film resolves to be a character study equating crime to Cody’s sociopathic behavior; goodness or principles have no place in the discussion. In the end, the film is about a troubled mind, leaving the audience to savor James Cagney’s performance. Cagney’s stage actor style could have easily been too broad for the screen, but his larger-than-life presence and long-established natural appeal make Cody Jarrett into an iconic character. Every moment he’s onscreen offers some ingenious and unscripted touch, transforming Cody from a despicable psycho into a broken person and criminal madman. In one scene after the prison escape, Cody unloads a few rounds into his trunk where he’s locked prison traitor Roy Parker. “Stuffy, huh?” he says, munching happily on a chicken wing. “I’ll give you a little air,” and then ventilates the trunk with bullets, signaling Cagney’s enduring talent for turning screen violence into a macabre charisma.

By 1949, the studio system had begun to wind down under the threat of television, and top talent such as the Bogarts and De Havillands left their former studios to pursue independent projects. White Heat represents the final major gangster picture for both Warner Bros. and James Cagney, containing the sensationalist airs of a 1930s gangster yarn with the more introspective psychology and violence characteristic of postwar filmmaking. The Warners had successfully rekindled their former glory one last time, while the modern era allowed Walsh and Cagney to push limits to create something that pays homage to a decades-old genre with new Freudian complexity otherwise absent from the earlier gangster pictures. Upon the release of this revisionist film, Cagney’s performance reminded audiences why his signature hard-nosed dynamism (from The Public Enemy to Angels with Dirty Faces) and intricately detailed characterizations (from Yankee Doodle Dandy to Man of a Thousand Faces) made him among the period’s greatest screen actors. Today, the picture stands not only as the last hurrah in Cagney’s tradition of playing gangsters, but perhaps the greatest single example of the actor’s onscreen magnetism: his ability to evoke equal measures of humanity and brutality, the thrill of his finger on the trigger and his clenched fists, the way his lips curl and voice snarls smooth, and how his acting style is no less nuanced for its grandiosity. Ahead of its time yet encompassing what came before, White Heat might be the perfect screen metaphor for Cagney himself.

By 1949, the studio system had begun to wind down under the threat of television, and top talent such as the Bogarts and De Havillands left their former studios to pursue independent projects. White Heat represents the final major gangster picture for both Warner Bros. and James Cagney, containing the sensationalist airs of a 1930s gangster yarn with the more introspective psychology and violence characteristic of postwar filmmaking. The Warners had successfully rekindled their former glory one last time, while the modern era allowed Walsh and Cagney to push limits to create something that pays homage to a decades-old genre with new Freudian complexity otherwise absent from the earlier gangster pictures. Upon the release of this revisionist film, Cagney’s performance reminded audiences why his signature hard-nosed dynamism (from The Public Enemy to Angels with Dirty Faces) and intricately detailed characterizations (from Yankee Doodle Dandy to Man of a Thousand Faces) made him among the period’s greatest screen actors. Today, the picture stands not only as the last hurrah in Cagney’s tradition of playing gangsters, but perhaps the greatest single example of the actor’s onscreen magnetism: his ability to evoke equal measures of humanity and brutality, the thrill of his finger on the trigger and his clenched fists, the way his lips curl and voice snarls smooth, and how his acting style is no less nuanced for its grandiosity. Ahead of its time yet encompassing what came before, White Heat might be the perfect screen metaphor for Cagney himself.

Bibliography:

Bordwell, David, et al. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Columbia University Press, 1985.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

McCabe, John. Cagney (Paperback ed.). Aurum Press, 2002.

McGilligan, Patrick. Cagney: The Actor as Auteur. A. S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1975.

Warren, Doug; Cagney, James. Cagney: The Authorized Biography. St. Martin’s Press., 1986.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review