The Definitives

WALL·E (2008)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

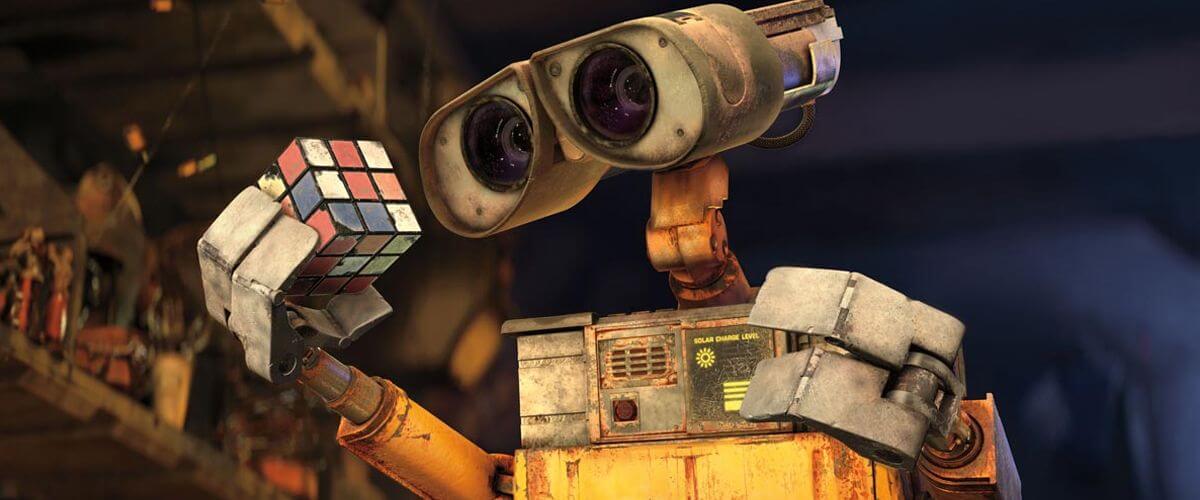

Somewhere in space, a haze of dormant satellites orbits the not-so-blue planet Earth. Beneath the planet’s rusty outer atmosphere stand ancient skyscrapers, and beside them, towers built from cubes of garbage. In between these towers, a solar-powered trash compacting robot, named WALL•E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter–Earth-class), maneuvers on the dusty trails he’s cleared, accompanied only by a squeaking cockroach companion. All other bots of WALL•E’s kind have been out of commission for some time, perhaps hundreds of years. Still, each day for the bot is the same: In the morning, he powers his solar cell until a Mac startup sound indicates he’s fully charged. Then he heads out into the wasteland, compacts trash into countless cubes and uses them to build his garbage towers, and scrounges for objects to be filed away in his collection of knick-knacks: bobbleheads, a spork, and a diamond ring case (the diamond ring itself does not interest him). Unique among his findings one day is a small plant, a vine with a few pathetic leaves peeking out from a spot of soil. WALL•E files it away inside his shelter amid rows upon rows of other carefully organized curios. As he tidies up, he watches a few scenes from his one and only Betamax cassette, Hello Dolly (1969), and sings the melodic beats of the upbeat “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” followed by the love song “It Only Takes a Moment”, after which he yearns for someone’s hand to hold. After rocking himself to sleep, a day in the life of WALL•E has come to an end, but the solitude and loneliness of this evident dreamer are enough to evoke tears.

WALL•E, Pixar Animation Studios’ ninth feature, and their very best, channels an incredible wellspring of emotion from an unlikely story about the last robot on Earth, filling us with warmth, empathy, and the desire to engage in our world. Written and directed by Andrew Stanton, the film contains a raw emotional center atop of several strains of social commentary, each an exacting reflector designed to rouse its audience out of their cultural apathy. How strange that an animated, G-rated feature should take on how we favor our rampant consumerism over our environment; or the way our pointedly American consumerist drives celebrate technology that isolates us from one another, confining our involvement in the human race and diminishing our own usefulness on the planet. Regardless of these lofty subtexts, WALL•E is foremost a love story, and a particularly joyous and moving one at that. With a perfect balance of poignant storytelling and inescapable meaning, WALL•E also remains unique for being an almost silent, mostly dialogue-less, largely pantomimed film. From its themes to its execution, Stanton and his team of animators design a resounding work of commercial art. More than any other Pixar release, it puts forth animation not as a genre unto itself, but as a medium in which the possibilities are limitless.

One of the first animators hired by Pixar in the late 1980s, Stanton played a creative role in their first feature, Toy Story (1995), as a writer and artist, and he later directed A Bug’s Life (1997) and Finding Nemo (2003). Stanton conceived the idea for WALL•E during a formative lunch in 1994 with other Pixar mainstays. The topic of the lunch’s conversation was how to follow-up Toy Story. Alongside John Lasseter (Pixar’s CEO), Joe Ranft (head of Pixar’s story department), and Pete Docter (one of Pixar’s future directors), Stanton helped conceive ideas for future film concepts such as A Bug’s Life, Monsters, Inc., and Finding Nemo. During the discussion, Stanton asked, “What if mankind had to leave Earth and somebody forgot to turn off the last robot?” Essentially, his idea was an entire film about an R2D2-like character, or the desk lamp character from Pixar’s iconic first short, Luxo Jr. (1986). “I just thought that was the saddest character I had ever heard of,” Stanton later reflected. But an entire film about a robot was unconventional, even for Pixar, so the concept was stored away at the time, considered too risky for a studio that had not yet debuted its first computer-animated feature.

One of the first animators hired by Pixar in the late 1980s, Stanton played a creative role in their first feature, Toy Story (1995), as a writer and artist, and he later directed A Bug’s Life (1997) and Finding Nemo (2003). Stanton conceived the idea for WALL•E during a formative lunch in 1994 with other Pixar mainstays. The topic of the lunch’s conversation was how to follow-up Toy Story. Alongside John Lasseter (Pixar’s CEO), Joe Ranft (head of Pixar’s story department), and Pete Docter (one of Pixar’s future directors), Stanton helped conceive ideas for future film concepts such as A Bug’s Life, Monsters, Inc., and Finding Nemo. During the discussion, Stanton asked, “What if mankind had to leave Earth and somebody forgot to turn off the last robot?” Essentially, his idea was an entire film about an R2D2-like character, or the desk lamp character from Pixar’s iconic first short, Luxo Jr. (1986). “I just thought that was the saddest character I had ever heard of,” Stanton later reflected. But an entire film about a robot was unconventional, even for Pixar, so the concept was stored away at the time, considered too risky for a studio that had not yet debuted its first computer-animated feature.

Not until long after Pixar had established itself would the writer-director return to the idea of an isolated robot left on Earth. During the final stages of Finding Nemo’s production, Stanton remembered his lone survivor robot idea and steeped himself in the concept that would eventually become WALL•E—though he did not yet know why humans had left Earth, nor did he know his robot’s name. He became engrossed, exploring the main character’s design. He pondered how to establish the robot’s situation with elegant animation, emphasizing physical behavior over words. Fortunately, Finding Nemo’s massive performance at the worldwide box-office afforded Stanton leverage to explore his ideas with Pixar and the distributors at Disney. In 2004, Stanton should have been on vacation after his long production on Finding Nemo; instead, under the radar, he developed the first twenty minutes of the picture with just a few storyboard artists and an editor on his team. Finally, he presented his developmental work to Pixar’s foremost executives, John Lasseter and Steve Jobs, who greenlit Stanton’s concept.

Originally titled “Trash Planet” and then the oddly punctuated “W.A.L.-E.”, Stanton’s initial development of the story alongside Docter consisted of setup alone. Acts two and three were a mystery to the writer-director, and over the course of Stanton’s various scripts and brainstorming sessions, he considered incorporating elements of an alien race and a robot rebellion, both of which were scrapped. Rather than write in WALL•E’s beeps and tones, Stanton wrote dialogue for what each of those beeps meant to convey. Legendary sound designer Ben Burtt, responsible for R2D2’s sounds and other countless iconic noises from Star Wars (1977), would voice the WALL•E character and create a number of the film’s robotic sound effects. Stanton used Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay for Alien (1979) as a model for how to encapsulate visually complicated, thematically dense, and overall loaded scenes to minimalist, almost poetic effect. The first moments of the screenplay evoke as much: “Stars. The upbeat show tune, Put On Your Sunday Clothes, plays. More stars. Distant galaxies, constellations, nebulas… A single planet. Drab and brown. Moving towards it. Pushing through its polluted atmosphere.” The writing is simple but evocative, not unlike the film itself.

Originally titled “Trash Planet” and then the oddly punctuated “W.A.L.-E.”, Stanton’s initial development of the story alongside Docter consisted of setup alone. Acts two and three were a mystery to the writer-director, and over the course of Stanton’s various scripts and brainstorming sessions, he considered incorporating elements of an alien race and a robot rebellion, both of which were scrapped. Rather than write in WALL•E’s beeps and tones, Stanton wrote dialogue for what each of those beeps meant to convey. Legendary sound designer Ben Burtt, responsible for R2D2’s sounds and other countless iconic noises from Star Wars (1977), would voice the WALL•E character and create a number of the film’s robotic sound effects. Stanton used Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay for Alien (1979) as a model for how to encapsulate visually complicated, thematically dense, and overall loaded scenes to minimalist, almost poetic effect. The first moments of the screenplay evoke as much: “Stars. The upbeat show tune, Put On Your Sunday Clothes, plays. More stars. Distant galaxies, constellations, nebulas… A single planet. Drab and brown. Moving towards it. Pushing through its polluted atmosphere.” The writing is simple but evocative, not unlike the film itself.

Stanton implemented an expressive character design, but when early images of WALL•E first appeared, detractors noted similarities between the film’s titular robot and Number 5 from Short Circuit (1986), or even the short, hunched alien from E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). However, Stanton insisted any inspiration from those films remains “unconscious”, and the true inspiration for WALL•E’s look comes from binoculars: “You don’t need a mouth, you don’t need a nose, you get a whole personality just from [them].” The adage about eyes being the window to the soul comes to mind. Stanton’s other major influence was expanding upon the look of Luxo Jr., the bouncing lamp who appears on Pixar’s animated logo.But, rather than imbue WALL•E with easily recognizable, personified features, Stanton sought to create a functional robot first, and then work within the design’s limitations to project human qualities. Being a trash-compacting bot, he gave WALL•E a functional square torso and tank tread. His neck extends, allowing his head to tilt in confusion, pull back in surprise, or eke forward in curiosity. None of these features conveys as much emotion as WALL•E’s reflective eyes: two lenses, each in framework set at an upturned, vulnerable angle, capable of expressing worlds of emotion at the change of their position.

For the film’s look, Stanton emulated the visual style of classic science-fiction films from yesteryear, consulting cinematographer Roger Deakins (who also consulted on Rango) and visual FX supervisor Dennis Muren (Star Wars) to create the believable illusion of lens effects—such as barrel distortion (where the frame rounds on the edges from a wide-angle lens) or lens flares (that occur from light reflections inside a camera). Deakins had achieved crisp and earthy visuals in titles like Barton Fink (1991) and There Will Be Blood (2007), and offered advice for how to depict light shining through a dusty atmosphere. Muren had long been the premier expert for integrating animated visuals into live-action footage, largely in works of sci-fi and fantasy. Together, they gave WALL•E photo-real details, playing with light in ways normally associated with live-action photography. For instance, a moment where WALL•E tries to outrun a tidal wave of shopping carts zooms in so quickly, the camera appears to lose focus for a moment. After the Deakins-Muren consultancy, Pixar changed the mathematic formulas that drove animation software responsible for creating realistic light. Indeed, there are moments among the early scenes in WALL•E where the audience could swear we were watching photography.

For the film’s look, Stanton emulated the visual style of classic science-fiction films from yesteryear, consulting cinematographer Roger Deakins (who also consulted on Rango) and visual FX supervisor Dennis Muren (Star Wars) to create the believable illusion of lens effects—such as barrel distortion (where the frame rounds on the edges from a wide-angle lens) or lens flares (that occur from light reflections inside a camera). Deakins had achieved crisp and earthy visuals in titles like Barton Fink (1991) and There Will Be Blood (2007), and offered advice for how to depict light shining through a dusty atmosphere. Muren had long been the premier expert for integrating animated visuals into live-action footage, largely in works of sci-fi and fantasy. Together, they gave WALL•E photo-real details, playing with light in ways normally associated with live-action photography. For instance, a moment where WALL•E tries to outrun a tidal wave of shopping carts zooms in so quickly, the camera appears to lose focus for a moment. After the Deakins-Muren consultancy, Pixar changed the mathematic formulas that drove animation software responsible for creating realistic light. Indeed, there are moments among the early scenes in WALL•E where the audience could swear we were watching photography.

Stanton further tested himself by giving WALL•E an earthbound sidekick, a cockroach, a character just as unlikely and challenging—and just as frequently associated with vermin—as the rat in Ratatouille. Stanton puts forth the cutest squeaking cockroach ever put to film; he could have chosen an adorable mouse or something more traditional, but his choice was logical since cockroaches are known survivors of earthly catastrophe. As with many aspects of the film, Stanton wasn’t interested in taking the easy way out. For example, it would have been much easier if Stanton just wrote actual dialogue for WALL•E to speak; except, he was far more interested in delivering a kind of silent film to his audience, where characters don’t exactly speak, but they share expressive phrases like “ta da” and “whoa”, or each other’s names. The effect is something like a Charles Chaplin picture, watching a rambunctious but hopelessly romantic hero. Early in the film, the arrival of a scouting vessel interrupts WALL•E’s routine. A slick, white robot named EVE appears like an Apple-brand egg born from a massive spaceship. She might be a mindless procedure bot, except when her vessel leaves, she jets across the dusty landscape, free.

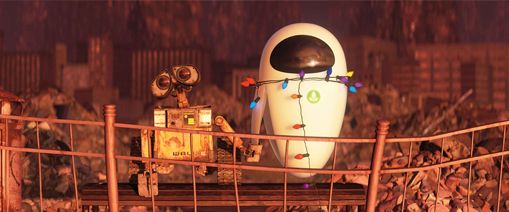

WALL•E becomes a pathetic, awkward kind of Tramp-esque figure, humiliating himself again and again, while vying for EVE’s attention. Our hero makes a series of unnoticed attempts at romance, such as making her a sculpture or waving from a distance, but she doesn’t take notice. WALL•E can only sigh, enamored by her indifference. Only when he saves her from a storm does she pay attention and begin to explore WALL•E’s findings in his shelter. EVE explores his rows of trinkets, while he prepares his Hello Dolly tape. But at that moment, she finds a lighter and ignites it. In this beautiful, heartrending scene, WALL•E looks at the flame, looks at her, and seems to understand love, only to once again be greeted by indifference when she refuses to take his hand. He tries one last thing to get EVE’s attention: he shows her the plant in its soil, both of which he placed inside an old shoe. She scans it, and this sets off a series of beeps and procedures in her that take the plant and contain it in her core. After these processes are complete, she’s left in an unresponsive standby mode. WALL•E tries for days to snap her out of it, keeping her safe in the meantime, desperate for his loneliness to end. All other work seems meaningless by comparison. And when a ship descends to Earth to recover EVE and return to its mother ship, he hitches a ride—hanging on all the way to Axiom, a space ship that has housed humanity for the last 700 years.

WALL•E becomes a pathetic, awkward kind of Tramp-esque figure, humiliating himself again and again, while vying for EVE’s attention. Our hero makes a series of unnoticed attempts at romance, such as making her a sculpture or waving from a distance, but she doesn’t take notice. WALL•E can only sigh, enamored by her indifference. Only when he saves her from a storm does she pay attention and begin to explore WALL•E’s findings in his shelter. EVE explores his rows of trinkets, while he prepares his Hello Dolly tape. But at that moment, she finds a lighter and ignites it. In this beautiful, heartrending scene, WALL•E looks at the flame, looks at her, and seems to understand love, only to once again be greeted by indifference when she refuses to take his hand. He tries one last thing to get EVE’s attention: he shows her the plant in its soil, both of which he placed inside an old shoe. She scans it, and this sets off a series of beeps and procedures in her that take the plant and contain it in her core. After these processes are complete, she’s left in an unresponsive standby mode. WALL•E tries for days to snap her out of it, keeping her safe in the meantime, desperate for his loneliness to end. All other work seems meaningless by comparison. And when a ship descends to Earth to recover EVE and return to its mother ship, he hitches a ride—hanging on all the way to Axiom, a space ship that has housed humanity for the last 700 years.

When WALL•E was first advertised, the trailers appropriately borrowed composer Michael Kamen’s hectic typewriter theme from Brazil (1985), Terry Gilliam’s wondrous, yet fatalistic look at the stifling bureaucracy of modern society. WALL•E is not unlike the hero of Gilliam’s film, Sam Lowry, played with awkward perfection by Jonathan Pryce. Both are lonely individuals awakened by imagination and love; and in pursuit of that love, both interrupt carefully regimented processes of the all-powerful System, and ultimately the status quo, with their heroic and romantic quest. Fortunately, WALL•E’s journey proves far more successful than Lowry’s complete mental breakdown in Brazil’s final sequence, but the comparisons remain. With his arrival in Axiom, WALL•E interrupts the smoothly running system of automation, whereby humans have devolved into bulbous, helpless, baby-like drones. A varied workforce of robots takes care of every chore and answers every human need, leaving the humans to grow wider and more complacent. In the quarters of Axiom’s Captain (voiced by Jeff Garlin), we see the long line of captains before him, and how humans have progressed from real-life humans into increasingly fat, and increasingly animated, blobs.

Indeed, WALL•E’s most daring facet must be its depiction of humanity, and how its portrayal of humans represents a blow to consumerism, as well as our society’s cultural and social apathy. Humans have turned themselves into veritable babies in the film, their desires for comfort and a literally laid-back lifestyle find them coddled by the robots running Axiom, all commanded by the ship’s autopilot program, dubbed AUTO. Stanton’s film suggests the outlandish degree of leisure follows the consumerist impulse. From our first moments on Earth in the film’s initial scenes, we see logos everywhere—specifically, one logo: Buy ‘N’ Large (or BnL), the brand stamped on soft drink cups, trains, gas stations, various buildings, and even the Axiom spaceship. “We’ll clean up the trash while you’re away,” promises an advertisement for off-world living on the Axiom spaceship where there’s “no need to walk” with hover chairs. BnL supplies “everything you need to be happy” on Axiom, and as a result, humans have evolved into isolated, chubby babies, addicted to their screens and oblivious to the world around them.

Indeed, WALL•E’s most daring facet must be its depiction of humanity, and how its portrayal of humans represents a blow to consumerism, as well as our society’s cultural and social apathy. Humans have turned themselves into veritable babies in the film, their desires for comfort and a literally laid-back lifestyle find them coddled by the robots running Axiom, all commanded by the ship’s autopilot program, dubbed AUTO. Stanton’s film suggests the outlandish degree of leisure follows the consumerist impulse. From our first moments on Earth in the film’s initial scenes, we see logos everywhere—specifically, one logo: Buy ‘N’ Large (or BnL), the brand stamped on soft drink cups, trains, gas stations, various buildings, and even the Axiom spaceship. “We’ll clean up the trash while you’re away,” promises an advertisement for off-world living on the Axiom spaceship where there’s “no need to walk” with hover chairs. BnL supplies “everything you need to be happy” on Axiom, and as a result, humans have evolved into isolated, chubby babies, addicted to their screens and oblivious to the world around them.

Technology is not inherently bad. Automation creates the potential of having more free time to explore the things that interest or excite us—to make further advancements in our personal relationships or the betterment of humankind. However, humans, both in the film and in real life, have become lazy and self-satisfied, dependent on automation, increasingly helpless, and ever more distanced from one another by the conveniences that were meant to bring us closer together. Stanton hopes to snap his audience out of complacency so they engage in the world, to see and interact with the natural beauty of the Earth and each other. “I wanted to show that our programming is the routines and habits that distract us to the point that we’re not really making connections to the people next to us,” Stanton said. And while audiences often read the film’s depiction of overweight humans as a critique of the American obesity epidemic, WALL•E has more to say about humans disengaging from life and allowing automation to transform them into a helpless species. A crumbling environment and obesity are two symptoms of a much deadlier disease: indifference.

Though WALL•E disrupts the mechanism of indifference, this is not an outright anti-establishment film, as the music suggests. Our hero interferes with stressed steward bot named Mo, who is fixated on cleaning “foreign contaminants”; the symbiotic relationship between human blobs and their screens; and finally the AUTO-pilot conspiracy to keep humans from recolonizing Earth. Stanton’s intended Christian themes (WALL•E as Adam, EVE as Eve, together bringing a new Genesis to Earth)notwithstanding, the film demonstrates how humanity has developed without the necessary driving force of progress because humans have fully integrated technology as a method of comfort. How ironic a lesson, then, because its teachers are robots. For certain, WALL•E might feel like a nightmarish cautionary tale against the dangers of so abundantly embracing such technology—that is, if it were not so wonderfully balanced by its elements of romance. Thomas Newman’s score plays on this balance with mischievous melodies in Axiom, contrasted by the swell of romantic notes in scenes between WALL•E and EVE. Furthermore, consider the film’s use of Hello Dolly’s “Put On Your Sunday Clothes”—the song encapsulates our hero’s desire for more than his “hick town” to discover “there’s lots of world out there”. To be sure, in lieu of original songs, “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” takes the place of a musical’s typical “I Want” tune. The message also resonates, albeit indirectly, for the film’s human characters, who must break free of their self-imposed establishment of isolation and return to Earth. Also from Hello Dolly, the song “It Only Takes a Moment” creates WALL•E’s understanding of romance, as he watches Michael Crawford and Marianne McAndrew hold hands, sing their dreamy verses, and fall in love.

Though WALL•E disrupts the mechanism of indifference, this is not an outright anti-establishment film, as the music suggests. Our hero interferes with stressed steward bot named Mo, who is fixated on cleaning “foreign contaminants”; the symbiotic relationship between human blobs and their screens; and finally the AUTO-pilot conspiracy to keep humans from recolonizing Earth. Stanton’s intended Christian themes (WALL•E as Adam, EVE as Eve, together bringing a new Genesis to Earth)notwithstanding, the film demonstrates how humanity has developed without the necessary driving force of progress because humans have fully integrated technology as a method of comfort. How ironic a lesson, then, because its teachers are robots. For certain, WALL•E might feel like a nightmarish cautionary tale against the dangers of so abundantly embracing such technology—that is, if it were not so wonderfully balanced by its elements of romance. Thomas Newman’s score plays on this balance with mischievous melodies in Axiom, contrasted by the swell of romantic notes in scenes between WALL•E and EVE. Furthermore, consider the film’s use of Hello Dolly’s “Put On Your Sunday Clothes”—the song encapsulates our hero’s desire for more than his “hick town” to discover “there’s lots of world out there”. To be sure, in lieu of original songs, “Put On Your Sunday Clothes” takes the place of a musical’s typical “I Want” tune. The message also resonates, albeit indirectly, for the film’s human characters, who must break free of their self-imposed establishment of isolation and return to Earth. Also from Hello Dolly, the song “It Only Takes a Moment” creates WALL•E’s understanding of romance, as he watches Michael Crawford and Marianne McAndrew hold hands, sing their dreamy verses, and fall in love.

Another borrowed musical cue comes from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), when the Captain, determined to confront AUTO, struggles to get out of his hover chair, and finally rises to his feet—a moment set to the crescendos of Johann Strauss’ Thus Spake Zarathustra, as popularized by Kubrick’s use of the piece. Likewise, AUTO bears a cagey resemblance to HAL-9000 from Kubrick’s film and goes just as mad, locking the Captain in his quarters and taking over Axiom. Indeed, AUTO even ejects our hero into space, not unlike HAL-9000 did to an ill-fated human crewmember. Fortunately, WALL•E survives the vacuum and dances in weightlessness alongside EVE, one of the film’s most enchanting scenes. WALL•E’s final set of references comes during the end credits, which chronicle what happened to humanity after recolonizing Earth, and does so by a historical progression of art forms. This gorgeous sequence charts the styles of ancient cave paintings, mosaics, frescoes, impressionism, and so on, alongside the advancement of humanity on the newly recolonized Earth. At the end of this artistic progression should have been Pixar, the latest form of high art. However, as the end credits scroll upward, digitized 8-bit animations of WALL•E, EVE, and their cockroach friend appear. Perhaps this marks the origins of computer animation, which led to Pixar’s arrival as the premier animation house working in cinema.

Stanton’s unlikely story produced one of Pixar’s most expensive films ($180 million) and earned back nearly three-times its budget at the worldwide box-office. WALL•E also earned the Best Animated Feature award at the Golden Globes, and was nominated for five Academy Awards (Best Original Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Original Song, Sound Editing, and Sound Mixing), winning the Best Animated Feature category. Many balked that WALL•E was not nominated for Best Picture as well, since dozens of critics place the film on their Top 10 lists in 2008. The accolades go on and on, continuing in subsequent years. The British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine ranked it second on a list of the all-time best animated features, just behind Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro (1988). The late critic for Time magazine, Richard Corliss, named the film the best movie of the 2000s. To be sure, the power of Stanton and Pixar’s storytelling in WALL•E was relevant upon its release and continues to grow more relevant as our society gradually turns itself into the humans depicted in the film. And though audiences have yet to heed the warnings in WALL•E, its message remains ever more powerful as time goes on, its call for love ever more necessary.

Stanton’s unlikely story produced one of Pixar’s most expensive films ($180 million) and earned back nearly three-times its budget at the worldwide box-office. WALL•E also earned the Best Animated Feature award at the Golden Globes, and was nominated for five Academy Awards (Best Original Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Original Song, Sound Editing, and Sound Mixing), winning the Best Animated Feature category. Many balked that WALL•E was not nominated for Best Picture as well, since dozens of critics place the film on their Top 10 lists in 2008. The accolades go on and on, continuing in subsequent years. The British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine ranked it second on a list of the all-time best animated features, just behind Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro (1988). The late critic for Time magazine, Richard Corliss, named the film the best movie of the 2000s. To be sure, the power of Stanton and Pixar’s storytelling in WALL•E was relevant upon its release and continues to grow more relevant as our society gradually turns itself into the humans depicted in the film. And though audiences have yet to heed the warnings in WALL•E, its message remains ever more powerful as time goes on, its call for love ever more necessary.

In their dependence on punchy colloquialisms, meta-humor, and attention-deficit animation, other animation studios lend little substance to their animated “family” or “children’s” entertainment. In fact, entertainment, and entertainment alone, is often what animation houses like DreamWorks, Fox, and others have resolved to produce. With its earlier titles, and in particular WALL•E, Pixar, too, offers entertainment, but of another kind entirely. Their entertainment transcends the otherwise limitless visual possibilities of animation to fulfill a rare narrative significance. WALL•E stands as the studio’s crowning achievement: just as experimental as Luxo Jr., just as revolutionary as Toy Story, except a far more singular work of art than anything they produced before or after. It’s a masterpiece among Pixar’s many masterpieces. Artistic yet accessible, poignant without overt sentimentality, and enlightening without being preachy—Stanton and Pixar achieved a motion picture that goes beyond what any major animation studios have done, or even aspire to do. Their elegant animation realizes a world teeming with life. And how extraordinary that a small robot, with limited speech and only the expressions on his mechanical face, serves as a conduit for that like. WALL•E represents humanity’s innate desire for love, and a greater feeling of connectedness to everything around us, in a film that is a work of art first, commercial cinema second.

Bibliography:

Auzenne, Valliere Richard. The Visualization Quest: A History of Computer Animation. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch. New York: Knopf, 2008.

Thomas, Bob. The Art of Animation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review