The Definitives

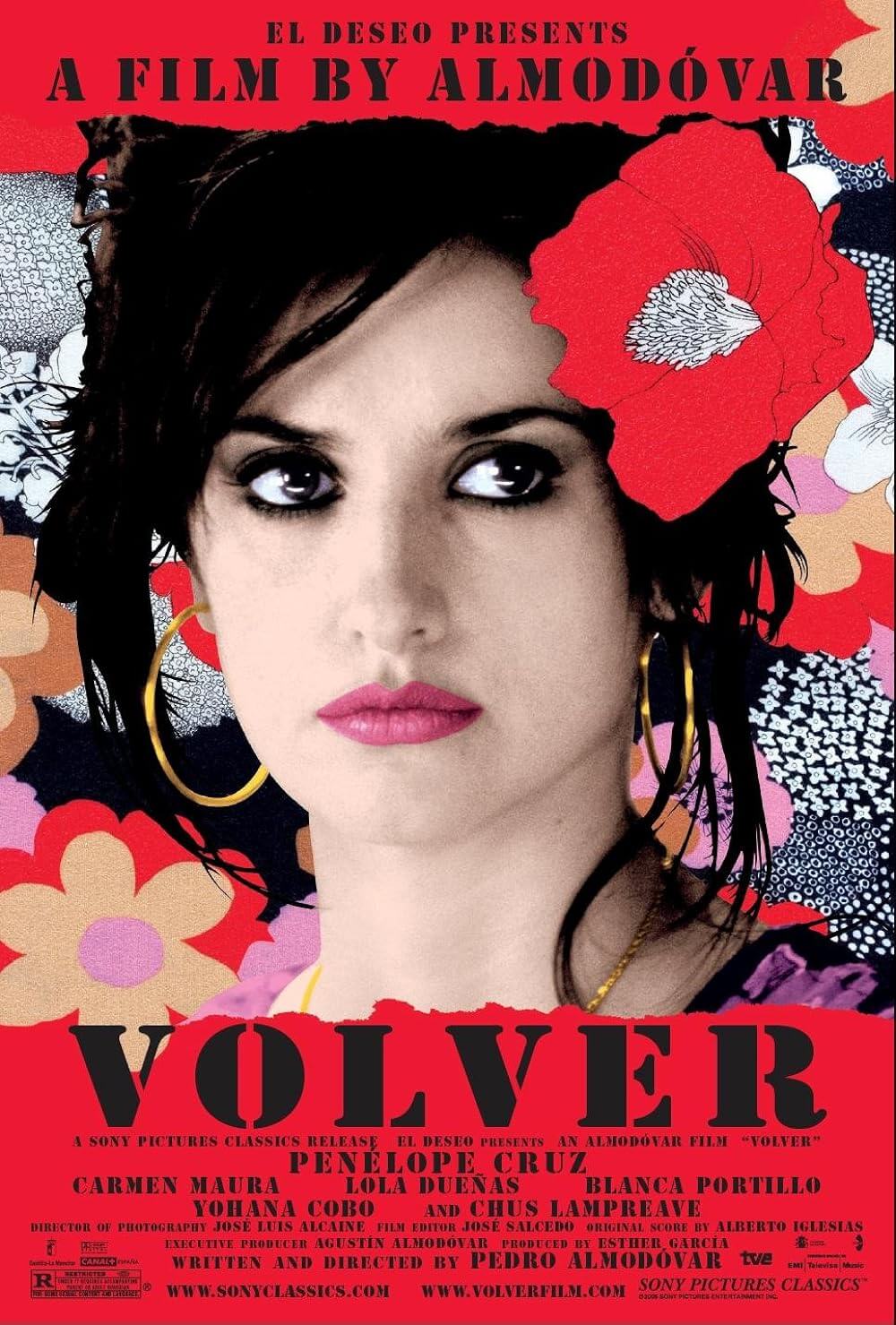

Volver (2006)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Pedro Almodóvar’s Volver takes the name of a tango first performed by Carlos Gardel in 1934. Meaning “to return” or “come back,” the film’s title—signaled by the song’s lyrics, “I’m afraid of the meeting, With the past that has returned, To confront my life”—reflects the filmmaker’s longtime obsessions. Almodóvar’s films often dwell on desire, self-discovery, and identity in relation to the haunting presence of Spain’s traumatic past. His intensely personal output teems with national and biographical influences, from allusions to his mother and childhood to his loving appreciation of international cinema—the more melodramatic, the better. Though his influences remain unmistakable, Almodóvar’s artistic inspirations never distract from his wildly distinct perspective. His masterful treatment of Volver encapsulates these many authorial preoccupations, proclivities, and hang-ups, and despite its ambitious layering, the film weaves a luminous and enchanting intertextual tapestry. In the macro, the film addresses the scars of Francoism in the collective memory; in the micro, it explores personal histories afflicted by the return of the repressed. Beautifully shot, structured, and acted, Almodóvar’s film sees the past repeat itself, the dead come back to life, and the painfully concealed return to the fore. Volver is about how things that seem dead and gone are sometimes inextricably part of our lives.

Volver is difficult to describe, which is typical for a film by Almodóvar. The unclassifiable plot contains rape, murder, terminal cancer, pedophilia, and a ghost, yet the material feels accessible, charming, endearing, and often funny. Its mixture may seem incongruous, but that’s Almodóvar for you. Draw a line to represent every maneuver in the average Almodóvar scenario, and the line would zig-zag every which way. His films contain a blend of genres and tonal shifts that miraculously come together to feel strangely balanced. Their eclecticism is legendary. Although some prove more dramatic or comedic than others, his best films have a bit of everything. His stylistic barroquismo is boundlessly transgressive—a richly composed aesthetic with full consideration of the viewer’s sensuous experience. He taps into every visual, aural, and emotional receptor. Volver alone has elements of Italian Neorealism, Sirkian melodrama, Hitchcockian suspense, and screwball comedy worthy of Howard Hawks. Through the intentional artifice composed of pastiche, genre, kitsch, and allusionism, which combine into a meticulous mise-en-scène, Almodóvar’s stories unfold with all the unpredictability of life. His films usually begin by telling one story only to transition into another one entirely, often by confronting his country’s history with raw emotional realism. The most precise way to describe Volver, then, appears during the opening credits: “Un film de Almodóvar”—a surname so distinct, it needs no given name to clarify it.

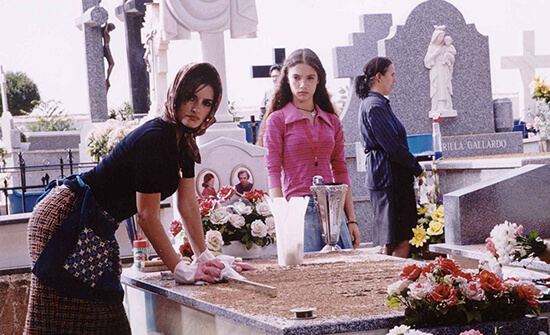

However, Volver, released in 2006 to widespread acclaim, is an exceptional Almodóvar film packed with intertextuality. The story reaches into the past, and not only its characters’ and country’s pasts but Almodóvar’s as well. Part of the film takes place in La Mancha, the region featured in Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and the place of Almodóvar’s birth. Shooting Volver on location, Almodóvar injects unchartable personal reference points into the film—a longing for his childhood home, the innocence of youth, and the nurturing comfort of his mother (as the song’s lyrics reflect: “And although I didn’t want to return, One always returns to their first love, The old street where the echo said, ‘Your life’s your own, your loving is your own.’”). To be sure, the film is another in a long line of Almodóvar films about mothers. Even so, it resists becoming a maudlin or an overserious affair, regardless of how any plot description may sound. Signaled with the Spanish song “Las espigadoras” (the gleaners), about women working in farm fields, the film opens in a cemetery populated by women, mostly widows, cleaning the tombstones of their loved ones. Among them, sisters Raimunda (Penélope Cruz) and Sole (Lola Dueñas), along with Raimunda’s daughter Paula (Yohana Cobo), have traveled from Madrid to pay their respects to the sisters’ parents. The sight of so many women remembering their loved ones, futilely cleaning in the harsh East wind, may appear curious to Paula. Still, Raimunda and Sole know this is a communal tradition in Alcanfor de las Infantas—a village where the women greet each other with warm hugs and loud dos besos.

However, Volver, released in 2006 to widespread acclaim, is an exceptional Almodóvar film packed with intertextuality. The story reaches into the past, and not only its characters’ and country’s pasts but Almodóvar’s as well. Part of the film takes place in La Mancha, the region featured in Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and the place of Almodóvar’s birth. Shooting Volver on location, Almodóvar injects unchartable personal reference points into the film—a longing for his childhood home, the innocence of youth, and the nurturing comfort of his mother (as the song’s lyrics reflect: “And although I didn’t want to return, One always returns to their first love, The old street where the echo said, ‘Your life’s your own, your loving is your own.’”). To be sure, the film is another in a long line of Almodóvar films about mothers. Even so, it resists becoming a maudlin or an overserious affair, regardless of how any plot description may sound. Signaled with the Spanish song “Las espigadoras” (the gleaners), about women working in farm fields, the film opens in a cemetery populated by women, mostly widows, cleaning the tombstones of their loved ones. Among them, sisters Raimunda (Penélope Cruz) and Sole (Lola Dueñas), along with Raimunda’s daughter Paula (Yohana Cobo), have traveled from Madrid to pay their respects to the sisters’ parents. The sight of so many women remembering their loved ones, futilely cleaning in the harsh East wind, may appear curious to Paula. Still, Raimunda and Sole know this is a communal tradition in Alcanfor de las Infantas—a village where the women greet each other with warm hugs and loud dos besos.

Ghosts and long-held family secrets reside at the film’s center; when revealed, they indicate patterns of behavior and trauma from one generation to the next. For example, questions linger about how Raimunda and Sole’s parents died. As Raimunda tells it, they burned to death in a fire in each other’s arms. The same day marked the disappearance of the mother of a family friend, Agustina (Blanca Portillo), leaving uncertainties about a possible connection between the two events. In the village, Augustina watches over Raimunda and Sole’s elderly Aunt Paula (Chus Lampreave), who talks as though her sister Irene, Raimunda and Sole’s mother, were still alive. Locals also claim to have seen Irene’s ghost around their Aunt Paula’s house, which the sisters admit “smells of Mom.” It might be unbelievable, except Aunt Paula is practically blind and incapable of taking care of herself. So who’s cooking and cleaning her house? Irene’s ghost? Other secrets have been buried even deeper. A pattern emerges involving men, particularly fathers, and incest, bringing to mind Chinatown (1972). Secrets notwithstanding, Raimunda doesn’t talk about the past—not her mother, not her father, not how she used to sing. Nevertheless, Volver is a story about Raimunda, a working-class mother from Madrid caught between her past and present, tradition and modernity, the country and the city. Her roots belong to her village and its venerable customs—and the mysteries they hold. But her life in the city, epitomized by her job mopping floors at the newly reconstructed Barajas Airport, represents her desire to fly away from her past.

Raimunda and Sole belong to a generation that, like Almodóvar, who grew up in rural poverty before moving to the cosmopolitan city, remains divided between worlds—marked by a dual identity, between their traditional past and fast-paced present. The sisters have settled in Madrid, but their origins in the countryside leave them split, while the young Paula, glued to her cell phone, is a product of modernity. But Raimunda and Sole are just old enough to remember the country under Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator from 1939 to 1975, who enforced an ordered society and the illusion that truth was unequivocal, which made life simple, assuming one conformed to his version of the truth. Of course, the world proved more complex and messy than Franco allowed. When he died in 1975, the end of Francoism brought about the so-called economic miracle in Spain that led to social freedom and material development. Spain in the 1980s became a liberalized and consumer-obsessed culture bent on ignoring rather than untangling the specters of their culture’s shared trauma. Before Almodóvar arrived in 1980 with his debut, Pepi, Luci, Bom, serious Spanish filmmakers received notoriety for remembering the country’s brutal Civil War (1936-1939). The prime example remains Víctor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive (1963), often cited as the greatest Spanish film of all time. After surviving their respective past traumas, Almodóvar and Raimunda focused primarily on escaping their past.

Almodóvar’s views about how his films represent the so-called new Spanish mentality after Franco remain cagey and unclarified, sometimes alternating from interview to interview. In early career interviews, he talks about his films exemplifying post-Franco Spain. Others suggest they exist independently of any conversation relating to Franco. “I never speak of Franco; I hardly acknowledge his existence,” he said in an interview about his initial films. “The stories unfold as if he had never existed.” His characters in Pepi, Luci, Bom and Labyrinth of Passion (1982) live in this moment, with clear motivations and often transgressive desires—from the publicly held penis size contest in the former to the unbridled nymphomania of the latter. If Almodóvar’s early films sought to free Spain from any association with Francoism through a punkish attitude and John Waters-level camp, that would change over time. The director would begin to confront Franco in somewhat indirect terms as his career progressed, referencing the before and after in films such as Dark Habits (1983). By the time he makes Live Flesh (1997), he employs flashbacks to the Francoist era, making the connections undeniable. But in a symbolic sense, most of Almodóvar’s films deal with Franco, before and after. He frequently tells stories rooted in the structure of a tragic past that cannot help but shape the present. While these concerns prove universal—everyone has events in their history that have made them who they are—it is particularly tempting to interpret Almodóvar’s films through the lens of Franco and the new Spanish liberalism.

Almodóvar’s views about how his films represent the so-called new Spanish mentality after Franco remain cagey and unclarified, sometimes alternating from interview to interview. In early career interviews, he talks about his films exemplifying post-Franco Spain. Others suggest they exist independently of any conversation relating to Franco. “I never speak of Franco; I hardly acknowledge his existence,” he said in an interview about his initial films. “The stories unfold as if he had never existed.” His characters in Pepi, Luci, Bom and Labyrinth of Passion (1982) live in this moment, with clear motivations and often transgressive desires—from the publicly held penis size contest in the former to the unbridled nymphomania of the latter. If Almodóvar’s early films sought to free Spain from any association with Francoism through a punkish attitude and John Waters-level camp, that would change over time. The director would begin to confront Franco in somewhat indirect terms as his career progressed, referencing the before and after in films such as Dark Habits (1983). By the time he makes Live Flesh (1997), he employs flashbacks to the Francoist era, making the connections undeniable. But in a symbolic sense, most of Almodóvar’s films deal with Franco, before and after. He frequently tells stories rooted in the structure of a tragic past that cannot help but shape the present. While these concerns prove universal—everyone has events in their history that have made them who they are—it is particularly tempting to interpret Almodóvar’s films through the lens of Franco and the new Spanish liberalism.

Like many Almodóvar films, Volver uses personal trauma as a metaphor for Franco. The film rushes into Hitchcockian territory when Raimunda returns home one night to find her daughter Paula outside, waiting, drenched by the rain, and visibly shaken. Paco (Antonio de la Torre)—introduced as a layabout who just lost his job, drinks too much, watches sports on the couch, and leers at his teenage daughter—tried to rape Paula. Groping her, he claimed, “I’m not your father,” and she responded by stabbing him. Raimunda finds his body in the kitchen and quickly cleans the crime scene to dispose of the evidence. Almodóvar shoots the sequence of Raimunda soaking up and scrubbing Paco’s blood from the same angles he uses to show her doing housework—as though covering up murder belongs on Raimunda’s list of maternal chores. She takes full responsibility and reminds her daughter, “Remember, I killed him.” In a moment of caught-in-the-act suspense, Emilio (Carlos Blanco), a neighbor who owns an out-of-business restaurant nearby, knocks on Raimunda’s door. In a darkly comic flourish, she explains the blood on her neck dismissively as “women’s problems”—an excuse that suggests menstrual blood but winks that repairing the damages of abusive men is a woman’s burden. Emilio leaves the keys to his restaurant with her in case a potential buyer comes along. There’s a certain whimsy to the way Emilio appears with the keys, unwittingly giving her a place to hide Paco’s corpse in the large restaurant freezer. In an equally whimsical way, a film crew just so happens to be shooting nearby, prompting Raimunda’s offer to cook for them and earn some extra cash to support her daughter in Paco’s absence. Or note how, at almost the exact moment of Paco’s death, Raimunda and Sole’s elderly Aunt Paula passes away in her sleep, prompting the spiritual return of their mother.

Almodóvar’s use of fantastical coincidence, coupled with shifts in tone and genre throughout Volver, nimbly maneuver from murder story to comic farce to family drama in minutes. He told Marsha Kinder, “You can say my films are melodramas, tragicomedies, comedies or whatever because I used to put everything together and even change genre within the same sequence and very quickly.” When Raimunda enlists her daughter to carry Paco’s body next door to hide it in the restaurant’s freezer, there’s a certain macabre humor in their clumsy luck. It channels Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) or The Trouble with Harry (1955), just as their desperation proves empathetic and gravely serious. And later, after Sole attends Aunt Paula’s funeral without her sister, a screwball subplot involves the ghost of her mother, Irene (Carmen Maura), who has returned to Madrid with Sole. Is she a literal ghost, or merely ghostly in the sense that she has returned from the distant past? Sole—who operates a beauty parlor out of her apartment, where Irene poses as a Russian immigrant who cannot speak Spanish—seems unconcerned about the distinction and bewildered by her mother’s return. Hilarious scenes set inside the parlor, where the wide-eyed Sole attempts to conceal Irene’s presence by loudly and awkwardly announcing Raimunda’s arrival so their mother can hide under the bed, do not distract from Raimunda’s more dramatic arc. They highlight it. When Raimunda thinks she smells her mother’s phantom farts in Sole’s apartment, the moment is funny but also heartrending when her olfactory senses connect with cherished memories of her mother’s flatulence, conjuring tears.

While many filmmakers offer similarly adroit shifts, Almodóvar explains, “The main difference is the private morality. I think one auteur is different from another because he has his own morality. When I say morality, I don’t mean ethics, it’s just a private point of view.” Almodóvar’s perspective aligns with Raimunda, and ironically, the murder becomes a catalyst for several changes in her life: Not only will she bury Paco, but she will unearth her past. Unlike, say, a classic Hollywood film that might punish Raimunda for covering up a murder, Almodóvar’s morality recognizes the necessity of such action. It’s no coincidence that “Paco” is short for “Francisco” and that Raimunda is stricken with the nagging reminder of Paco’s body in the freezer. Like Francisco Franco, Paco’s reach extends beyond the grave. His body becomes a persistent issue that Raimunda tries to hide away—first in a freezer, but then finally, buried at a river where they used to picnic. After she buries him, Paco may be gone, but the psychic trauma remains. The past contains many moral wrinkles for Raimunda. For instance, Paco was not Paula’s father after all. Still, he offered to help Raimunda raise Paula, which does not excuse his subsequent behavior but adds another layer of moral complexity to the proceedings. His death, combined with her eventual discovery that her mother has been staying with Sole, brings back the repressed trauma that her father raped her to produce Paula—who is her sister and daughter.

While many filmmakers offer similarly adroit shifts, Almodóvar explains, “The main difference is the private morality. I think one auteur is different from another because he has his own morality. When I say morality, I don’t mean ethics, it’s just a private point of view.” Almodóvar’s perspective aligns with Raimunda, and ironically, the murder becomes a catalyst for several changes in her life: Not only will she bury Paco, but she will unearth her past. Unlike, say, a classic Hollywood film that might punish Raimunda for covering up a murder, Almodóvar’s morality recognizes the necessity of such action. It’s no coincidence that “Paco” is short for “Francisco” and that Raimunda is stricken with the nagging reminder of Paco’s body in the freezer. Like Francisco Franco, Paco’s reach extends beyond the grave. His body becomes a persistent issue that Raimunda tries to hide away—first in a freezer, but then finally, buried at a river where they used to picnic. After she buries him, Paco may be gone, but the psychic trauma remains. The past contains many moral wrinkles for Raimunda. For instance, Paco was not Paula’s father after all. Still, he offered to help Raimunda raise Paula, which does not excuse his subsequent behavior but adds another layer of moral complexity to the proceedings. His death, combined with her eventual discovery that her mother has been staying with Sole, brings back the repressed trauma that her father raped her to produce Paula—who is her sister and daughter.

Raimunda is one of Almodóvar’s many characters who occupies a distinctly Spanish state of progressing from the past to the present, from the traditional to the modern, the repressive to expressive, the country to the city, from here to there. In most of Almodóvar’s twenty-first-century films, his protagonists must explore their pasts, usually by traveling to the country or returning to the home of a long-lost friend or family member. This is true of All About My Mother (1999), Talk to Her (2002), Bad Education (2004), Broken Embraces (2009), Julieta (2016), and Pain and Glory (2019). Given that Spain’s post-Franco rush toward globalization has made the countryside a signifier of the past, journeying to a village in an Almodóvar film means reconnecting with a former life—a literary motif true in most fiction. There, his characters search for love, work, answers, family, and escape. People like Raimunda must travel to maintain connections with their past, both geographical and cultural. But the past does not exist in a bubble; the massive wind farms on the drive to Alcanfor de las Infantas show how technology has changed since Don Quixote was chasing windmills. Almodóvar’s characters are always in the process of realizing that some aspect of their lives is unresolved and unfinished, in a state of flux from something old to something new. Symbolically, they are rural and migrant subjects who have moved into urban and modern spaces only to encounter cultural differences. They engage with otherwise marginalized and taboo characters such as transgender people, sex workers, terrorists, drug addicts, sexual predators, and even the occasional psychopath—figures either scarred by or associated with the country’s traumatic past. Yet, Almodóvar humanizes what would have been intolerable under Francoism, embracing difference with the postmodern necessity for cultural fluidity.

Volver’s most famous scene takes place during the film crew’s lavish wrap party at the restaurant. Raimunda realizes that her daughter has never heard her sing; she has repressed that part of herself, along with so much of her past. Overcome by nostalgia, she performs “Volver,” whose lyrics underscore Raimunda’s impending reunion with her mother and a forgotten part of herself. As she sings, her eyes filling with joyful tears, Almodóvar’s regular cinematographer José Luis Alcaine pans over various generations watching the performance, suggesting how the music has brought them together. Raimunda remains unaware that her mother watches from Sole’s car nearby, but she senses her uncanny presence. Cruz convincingly lip-syncs the song, performed by contemporary flamenco singer Estrella Morente, marking the convergence of cultures, generations, and perspectives that coexist through expression. The song comes from an Argentina-born singer who lived in France, and it’s performed in a restaurant with Hispanic motifs, from music to mojitos. Regina (María Isabel Díaz), the undocumented Latin American immigrant and prostitute, provides Raimunda with an authentic mojito recipe—not to mention the perfect criminal accomplice to bury Paco’s body. After learning about the murder, Regina dares not inform on Raimunda out of fear of capture, so she shrewdly negotiates a job bartending at the restaurant and quickly becomes a trusted ally. Almodóvar’s interest in the Spanish transnational community is apparent in his many international reference points, which denote Spain’s new state of liberal multiculturalism. Still, these themes remain secondary to Raimunda’s open-hearted performance and realization that she belongs to a larger community than she realized.

Raimunda and Regina offer just one example among many in Volver, and several other Almodóvar films, of how women form a supportive community. Under Franco’s patriarchal culture, women endured crimes ranging from domestic and sexual abuse to incest, which went unpunished. That shared trauma, along with the mortality rate of their husbands that necessitates communal grave cleaning, fosters the type of sisterhood shown in Volver. For instance, when Raimunda prepares her first meal at Emilio’s restaurant for the film crew, she relies on her community of women neighbors, who contribute pork and sweets without much fuss. Later, they serve tables and help Raimunda load the heavy freezer containing Paco’s body onto a rented truck. The women in Volver offer another in a long line of Almodóvar’s all-female ensembles. His films have showcased the lives of female punk rockers; bored, unsatisfied, or repressed housewives; drug-addicted and debauched nuns; film actresses; kidnapped porno stars; beleaguered authors; and transgender sex workers. But his favorite character must be a mother like Raimunda, who, typically so for the director, is less a sexless Madonna figure than a woman with desires and dimension. In a 1987 interview, Almodóvar characterized his use of mothers as distinctly Spanish: “When I’m writing about relatives, I just put in mothers, but I try not to put in fathers. I avoid it. I don’t know why. I guess I’m very Spanish.” By contrast, fathers usually appear as abusive, absent, or Francoist characters. As a result, Volver closely resembles the director’s What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984), featuring Carmen Maura as a desperate housewife who resorts to murder. Both feature women as wives and mothers who rally against their roles in a patriarchal and capitalist culture, which suppresses their desires and replaces them with domestic drudgery.

Raimunda and Regina offer just one example among many in Volver, and several other Almodóvar films, of how women form a supportive community. Under Franco’s patriarchal culture, women endured crimes ranging from domestic and sexual abuse to incest, which went unpunished. That shared trauma, along with the mortality rate of their husbands that necessitates communal grave cleaning, fosters the type of sisterhood shown in Volver. For instance, when Raimunda prepares her first meal at Emilio’s restaurant for the film crew, she relies on her community of women neighbors, who contribute pork and sweets without much fuss. Later, they serve tables and help Raimunda load the heavy freezer containing Paco’s body onto a rented truck. The women in Volver offer another in a long line of Almodóvar’s all-female ensembles. His films have showcased the lives of female punk rockers; bored, unsatisfied, or repressed housewives; drug-addicted and debauched nuns; film actresses; kidnapped porno stars; beleaguered authors; and transgender sex workers. But his favorite character must be a mother like Raimunda, who, typically so for the director, is less a sexless Madonna figure than a woman with desires and dimension. In a 1987 interview, Almodóvar characterized his use of mothers as distinctly Spanish: “When I’m writing about relatives, I just put in mothers, but I try not to put in fathers. I avoid it. I don’t know why. I guess I’m very Spanish.” By contrast, fathers usually appear as abusive, absent, or Francoist characters. As a result, Volver closely resembles the director’s What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984), featuring Carmen Maura as a desperate housewife who resorts to murder. Both feature women as wives and mothers who rally against their roles in a patriarchal and capitalist culture, which suppresses their desires and replaces them with domestic drudgery.

The similarities between Volver and What Have I Done to Deserve This? underscore the presence of several longtime Almodóvar collaborators. Penélope Cruz, of course, started acting for the director in Live Flesh and would continue to appear in many other films, including All About My Mother, Broken Embraces, I’m So Excited (2016), and Parallel Mothers (2021). But more importantly, Volver ends a seventeen-year break between the director and Carmen Maura, his muse for many of his most formative early films. Along with Chus Lampreave, who appears as Aunt Paula, Maura was a fixture in Almodóvar’s films throughout the 1980s. She starred in his edgy debut, Pepi, Luci, Bom, and also many of his breakout successes, such as Dark Habits, Matador (1986), Law of Desire (1987), and perhaps his biggest international success in his early period, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988). For those versed in Almodóvar’s filmography, Maura and Lampreave feel like literal and symbolic figures from the past who have returned to haunt Volver—in Maura’s case, pretending to be a ghost as Irene. How appropriate, given Maura’s status as a revenant figure from Almodóvar’s filmography. With younger but no less significant faces in Almodóvar’s career, Maura and Lampreave’s presence complements those of Cruz and Lola Dueñas, making the film a rare merging of collaborators from the past, present, and future.

Maura’s presence never overshadows Cruz, whose best performances have been under Almodóvar’s direction. Hollywood has rarely made good use of Cruz’s talent and range, reducing her to sexpot or love interest roles in many bland blockbusters. Her performance in Volver is arguably her best, earning her an Oscar nomination and a Goya win. Almodóvar models her appearance after the working-class women at the center of so many Luchino Visconti or Vittorio De Sica films starring Sophia Loren or Anna Magnani. In Volver, the director shows Irene watching Visconti’s Bellisima (1951) on television. The brief glimpse of Magnani mirrors Cruz’s appearance as Raimunda—her dark hair pulled back; her cleavage accentuated; her wardrobe comprised of simple, colorful outfits. Beautiful though she is, Almodóvar and Cruz avoid turning Raimunda into a product of the male gaze. Raimunda’s complexity and evident history capture both the performance’s range and the character’s realistic human detail. Her short temper and duty-bound exhaustion, compounded by her recent need to hide Paco’s body, create a hard surface that softens in rare moments. “Cruz almost perfectly embodies the confluence of realism and hyper-stylized fiction so central to [Almodóvar’s] work,” notes critic Carla Marcantonio. She becomes a maternal, protective figure derived from the director’s memories of his mother and his experiences with Italian Neorealism and melodrama. It’s no wonder he continued to cast Cruz as mother figures, most notably as a stand-in for his mother in Pain and Glory, followed by her central role in Parallel Mothers.

Given his concentration on women subjects, Almodóvar’s work has sometimes been compared to melodramas from classical Hollywood. He invites such contrasts by making direct references to Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray in many of his films—his characters always seem to be talking about, going to see, or even providing Spanish dialogue for a classic melodrama. Such films historically bring to mind an investigation of binary gender roles in so-called women’s films, such as Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), which raises questions about certain social norms for a middle-aged woman. Volver also draws influence from Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), a similar story that entails a self-reliant mother’s resolve, entrepreneurship, a troubled past, exposed secrets, and murder. Almodóvar uses melodrama to blur the lines in a nonbinary investigation of desire, drawing from melodrama’s roots in the French Revolution as a method of questioning the sacred order of the Church and State that crumbled with the monarchy. Similarly, Almodóvar uses melodrama in the wake of Franco’s repressive regime to explore the erosion of boundaries in Spain’s newfound and initially intoxicating freedom in a liberal democracy. In Volver, the order of Franco’s past becomes a site of moral and personal corruption that women must confront when the time comes: Raimunda eventually discovers Irene in Sole’s apartment—and what’s more, she is not a ghost but has been in hiding for years and therefore appears pale and ghostly. Mother and daughter finally share their respective traumas. Raimunda forgives Irene and puts to rest her lifelong resentment that her father’s sexual abuse went unnoticed. At the same time, Raimunda promises to one day tell Paula about her past. Almodóvar shows his embrace of melodrama and the interior world of women gracefully when Raimunda and Irene agree that their secrets are “Our business and no one else’s.”

Given his concentration on women subjects, Almodóvar’s work has sometimes been compared to melodramas from classical Hollywood. He invites such contrasts by making direct references to Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray in many of his films—his characters always seem to be talking about, going to see, or even providing Spanish dialogue for a classic melodrama. Such films historically bring to mind an investigation of binary gender roles in so-called women’s films, such as Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), which raises questions about certain social norms for a middle-aged woman. Volver also draws influence from Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), a similar story that entails a self-reliant mother’s resolve, entrepreneurship, a troubled past, exposed secrets, and murder. Almodóvar uses melodrama to blur the lines in a nonbinary investigation of desire, drawing from melodrama’s roots in the French Revolution as a method of questioning the sacred order of the Church and State that crumbled with the monarchy. Similarly, Almodóvar uses melodrama in the wake of Franco’s repressive regime to explore the erosion of boundaries in Spain’s newfound and initially intoxicating freedom in a liberal democracy. In Volver, the order of Franco’s past becomes a site of moral and personal corruption that women must confront when the time comes: Raimunda eventually discovers Irene in Sole’s apartment—and what’s more, she is not a ghost but has been in hiding for years and therefore appears pale and ghostly. Mother and daughter finally share their respective traumas. Raimunda forgives Irene and puts to rest her lifelong resentment that her father’s sexual abuse went unnoticed. At the same time, Raimunda promises to one day tell Paula about her past. Almodóvar shows his embrace of melodrama and the interior world of women gracefully when Raimunda and Irene agree that their secrets are “Our business and no one else’s.”

Volver is characteristic of Almodóvar’s later work through the recognition of the trauma that many of his early films actively ignored. But he told the New York Times in 2004, “Everything I am is a response to this place [Spain].” Men supply the familiar signs of physical and psychic scars inflicted on the country by the Civil War and forty years of Franco’s rule. Specifically, the father who raped Raimunda and cheated on Irene with Augustina’s mother only to be burned alive; there is also the stepfather who attempted to rape Paula only to be murdered and buried in secret. After decades of repressing its past, Spain is still maturing out of its enforced infancy and naivety under Franco, still finding ways to move beyond its relationship with its abusive father. Franco’s memory still haunts Spain even though he is dead and buried, much like Paco and Raimunda’s father. And those who dwell on the past, like Augustina, allow the trauma to eat away at them, symbolized by her terminal cancer—even if her obsessive investigation of their history leads to Raimunda’s reconciliation. The film sees the necessity of healing and growth out of trauma, as opposed to outright rebellion. Moreover, it recognizes the capacity for women to share in their trauma and better understand each other and their histories. Almodóvar acknowledges the necessity of the past and, as the titular song’s lyrics suggest, “to live, with the soul bound to a sweet memory.” People are products of their past, and understanding the melancholic relationship between past trauma and present conditions allows for healing conversations.

Look at the filmography of Pedro Almodóvar, and there’s a clear progression from his cinematic independence and defiance of Franco to his unburdening of the past. Some of his films reflect the comical and delightfully transgressive Almodóvar; others, the more severe and matured filmmaker. Most of his films, and his most complex and narratively intricate, such as Volver, offer examples of both sides. Accented by untold visual pleasures, passionate characters, and emotional intelligence, the film comes from a filmmaker who, in his late fifties at the time, started to look back and make peace as Raimunda does. His mastery of pastiche finds him incorporating influences from the past to discover new uses for melodrama and realism—familiar cinematic expressions that become reframed by his intertextual agenda. Almodóvar’s persistent allusionism reflects how his characters mine their past to understand the present; they embrace traditions and liberate their trauma to move beyond Francoism and its patriarchal dominance of Spain. Volver rests on a tender community of women who were forced together due to their trauma, and the film’s unlikely optimism comes out of how they resolve to share their histories and memories.

Bibliography:

Besas, Peter. Behind the Spanish Lens: Spanish Cinema under Fascism and Democracy. Arden Press, 1985.

Gutiérrez-Albilla, Julián Daniel. Aesthetics, Ethics and Trauma in the Cinema of Pedro Almodóvar. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

Kinder, Marsha, and Pedro Almodóvar. “Pleasure and the New Spanish Mentality: A Conversation with Pedro Almodóvar.” Film Quarterly, vol. 41, no. 1, University of California Press, 1987, pp. 33–44, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212326. Accessed 25 October 2021.

—. “Reinventing the Motherland: Almodóvar’s Brain-Dead Trilogy.” Film Quarterly, vol. 58, no. 2, University of California Press, 2004, pp. 9–25, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2004.58.2.9. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Marcantonio, Carla. “Review: Volver.” Cinéaste, vol. 31, no. 4, Cineaste Publishers, Inc., 2006, pp. 77–79, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41690411. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Ochoa, Debra J. “Music and Migratory Subjects in Almodóvar’s ‘Todo Sobre Mi Madre, Hable Con Ella’, and ‘Volver.’” Confluencia, vol. 29, no. 2, University of Northern Colorado, 2014, pp. 129–41, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43490040. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Pingree, Geoff. “Pedro Almodóvar and the New Politics of Spain.” Cinéaste, vol. 30, no. 1, Cineaste Publishers, Inc., 2004, pp. 4–8, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689799. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Richards, Arlene Kramer, et al. (editors). Pedro Almodóvar: A Cinema of Desire, Passion and Compulsion. International Psychoanalytic Books, 2018.

Straus, Frederick (editor). Almodóvar on Almodóvar. Revised edition. Faber and Faber, 2006.

Vernon, Kathleen M. “Melodrama against Itself: Pedro Almodóvar’s ‘What Have I Done to Deserve This?’” Film Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 3, University of California Press, 1993, pp. 28–40, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212901. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review