The Definitives

Videodrome (1983)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

When Max Renn stumbles across the pirated signal of an ultra-violent torture program called “Videodrome,” a friend warns him to beware. The show has a philosophy, and philosophies are dangerous. David Cronenberg also has a philosophy, and films like his 1983 breakthrough Videodrome remain dangerous for their equal parts intellect and visceral nature. Its philosophy questions whether media images have the power to influence our unconscious on their own, or if some kind of change occurs only when the viewer allows it. Amid themes of overstimulation and transmigration through technology, Cronenberg employs an arsenal of grotesque makeup effects that align with the hallucinatory science-fiction narrative, and he constructs an unforgettable experience where pain and desire are interchangeable, obscuring the lines between horror and eroticism to disturbing limits. Films like this rouse powerful reactions to their extreme metaphors and violent imagery; but then, there has never been a film quite like this one.

Whereas Cronenberg’s earlier work could be defined as exploitation or schlock or simple genre exploration, Videodrome defies characterization, even in the realm of horror and science-fiction, and it becomes the first of the director’s works to fully earn the title Cronenbergian. Its themes provide a roadmap for his future projects, yet they emerge in a presentation so perplexing and severe that the result can feel impenetrable. Inside, he explores functions of technology, violence in society and media, sexual repression, body horror, hallucination, paranoia, displacement, and sadomasochism, all themes addressed by Cronenberg in more specific, individual terms later in his career. The film both reflects on his previous efforts in the horror genre (Shivers a.k.a. They Came from Within, 1975; Rabid, 1977; The Brood, 1979; Scanners, 1981) and rises above those works and the reactions to them. Videodrome becomes a way for Cronenberg to scrutinize the “censorious notions” that plagued the reception of his early oeuvre, in turn substantiating his earlier films by providing them with new insights and exposing their auteuristic flourishes.

In many ways, the film represents a major step forward for the Canadian filmmaker, who in the early 1980s maintained a steady output of low-budget shockers, all reasonably profitable but none taken seriously from an artistic standpoint. Videodrome was also the last of Cronenberg’s tax shelter films and his first distributed by a major Hollywood studio, MCA/Universal. Tax shelter incentives encouraged local investors to bankroll Canadian films. Investors could write promissory notes to Canadian film studios, invest only a small sum despite their promise, and then write off the larger amount on their taxes. This loophole caused investors to wait until the fourth quarter to find a last-minute venture to make the fiscal year, leaving spring and summer month shoots all but nonexistent, and filmmakers scrambling to finish their film on a short deadline and potentially insecure budget.

In many ways, the film represents a major step forward for the Canadian filmmaker, who in the early 1980s maintained a steady output of low-budget shockers, all reasonably profitable but none taken seriously from an artistic standpoint. Videodrome was also the last of Cronenberg’s tax shelter films and his first distributed by a major Hollywood studio, MCA/Universal. Tax shelter incentives encouraged local investors to bankroll Canadian films. Investors could write promissory notes to Canadian film studios, invest only a small sum despite their promise, and then write off the larger amount on their taxes. This loophole caused investors to wait until the fourth quarter to find a last-minute venture to make the fiscal year, leaving spring and summer month shoots all but nonexistent, and filmmakers scrambling to finish their film on a short deadline and potentially insecure budget.

Backed by Canadian tax shelter dollars and set for distribution to wider audiences than Cronenberg had ever seen, Videodrome’s development went through revisions both in the screenwriting and production stages. His script was originally titled Network of Blood, embracing his penchant for titles that sound like classic horror (i.e. They Came From Within). But he rewrote his screenplay when he realized early on that his initial vision was too graphic for a film, a shocking notion given the potency of what ended up onscreen. In a reaction not dissimilar from that to Terry Gilliam’s production of Brazil in 1985, Universal head Sid Sheinberg tried to halt production once he finally read the script, but by then he was too late. Additional cuts were made when Cronenberg’s budget would simply not allow certain scenes to be realized, or when the team of effects wizard Rick Baker (working with a $500,000 effects budget) could not render a visual effect in the way the director had envisioned. Shooting took place in Toronto and wrapped just before the dawn of 1983, leaving the footage subject to Cronenberg’s brutal scrutiny.

During the editing process, Cronenberg test screened a 75-minute version that he later admitted was “incomprehensible,” and the audience’s reaction appropriately deemed the shortened film a mess. When he finally settled on an 89-minute cut, few of the studio executives overseeing the project knew what to make of it. Accordingly, the studio took no care finding the film’s audiences by targeting appropriate demographics—in this case, arthouse crowds open to the kind of sophisticated filmmaking on display. As Cronenberg recalled, “[The film] should have been handled as an art film, and been given slow, deliberate promotion, using critical response to promote it.” Conventional audiences responded with bewilderment, revulsion, and ultimately dismissal; this could not have surprised Cronenberg, whose output had never reached general audiences. Polarized critics voiced either confused or wildly enthusiastic reactions. Andy Warhol called the film the “Clockwork Orange of the 1980s,” and after seeing the film, John Carpenter (The Thing) called Cronenberg the “only real artist” in the horror genre. “He’s better than all of us,” Carpenter would say. On the other hand, Roger Ebert called it “one of the least entertaining films ever made.” Yet Videodrome harbors visuals that are outrageous even today and ideas which only in recent years have proved their prophetic authority.

James Woods stars as Max Renn, president of sleazy cable company Civic TV, a station peddling soft-core pornography and excessive violence to home viewers. To find his station’s next risqué new program, Renn meets with Hiroshima Video in a transaction modeled after a black market deal set in a derelict hotel, where Max watches excerpts from their show “Samurai Dreams,” a pitch he deems “too soft” (despite real-life Universal production head Bob Rehme demanding cuts to the explicit segment). Max wants something more: “I’m looking for something that’ll break through, y’know, something tough.” And Max’s satellite bootlegger Harlan (Peter Dvorsky) has just the thing: a “subterranean” signal known as “Videodrome” on which participants become victims of snuff TV—chained to an electrified wall, whipped, and eventually strangled to death. His interest piqued, Max researches the show’s origins to learn more, and meanwhile watches video recordings with new lover, Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry), who, flouting Max’s warnings, intends to appear on the show to satisfy her masochistic cravings.

In tracking down the source of “Videodrome,” Max visits the Cathode Ray Mission where he meets Bianca O’Blivion (Sonja Smits), daughter of Professor Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), who suggests that watching the “Videodrome” broadcast will cause Max to have hallucinations caused by a brain tumor generated by the broadcast. After suffering a number of these hallucinations, Max is contacted by Barry Convex (Leslie Carlson), the head of Spectacular Optical, a manufacturer of inexpensive eyeglasses, missile guidance systems, and “Videodrome.” In part of an ideological undertaking to cleanse North America of social derelicts who would watch the sort of filth advocated by Civic TV, Spectacular Optical developed “Videodrome” not only to purge the world of an undesirable element through fatal brain tumors but to turn them into programmable drones. Convex orders Max to kill his partners at Civic TV, which he does, and then Bianca. But Bianca reprograms Max to destroy “Videodrome” and in turn orders him to kill Harlan, a double-agent for Spectacular Optical, as well as Convex. After both men are dead, Max learns that he must transform into the “New Flesh” before he can destroy “Videodrome” completely; to do this, he must let his body die. With a gunshot to the head, Max begins a transformation from old flesh to new, ridding himself of the “Videodrome” signal.

After Max first watches a few seconds of “Videodrome” in Harlan’s lab, only 12 minutes into the film, the viewer should suspect the reality of everything that appears onscreen. Cronenberg gradually shifts the film into Max’s point of view as his hallucinations take over the picture. Apparent waking dreams give way to violent delusions and less obvious altered perceptions, the most memorable of which remains the vaginal slit that opens on Max’s stomach, later the receptor for a pulsating videotape containing orders from Spectacular Optical. Much like Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch (1991) or eXistenZ (1999), the film blends together reality and hallucination through narrative, and so watching Videodrome becomes an experience in asking oneself, What is real? Then again, as Brian O’Blivion would argue, “There is nothing outside our perception of reality.” Since the film develops from the perspective of a protagonist, who is both unreliable and who has no idea what is happening to him, how could the audience hope to fully grasp every plot turn along the way? Indeed, after multiple viewings, even the most attentive viewer may not “get” the film; comprehending it requires intuition and interpretation. Whether or not audiences can recount the details of the plot, a feeling of understanding prevails by the end, even if the audience cannot explain how they got there or how to articulate its meaning.

Hallucinations, a side-effect of the “Videodrome” signal, also provide the film’s most potent metaphor. They discharge the idea that exposure to sex and violence in the media is desensitizing or results in an emotionally numb viewer who seeks pleasure through visceral stimuli. In Videodrome, the torturous arena, the experience of watching graphic sex and violence, provides merely the bait for what Spectacular Optical considers social undesirables—it “opens up receptors in the brain and spine”—while the hook resides embedded into any television signal. As Bianca explains, the dangers of “Videodrome” can be hidden inside a test pattern, making television itself the weapon more than any content that appears onscreen, and any viewers subject to enslavement. To another extent, the O’Blivions see television as a social stabilizer, offering TV cubicles in their Cathode Ray Mission where the homeless are reconnected to society through television: “Watching TV will help patch them back into the world’s mixing board.” The weapon is not the brain-washing, brain-scrambling transmission of “Videodrome,” but television itself, which distances the viewer from their sense of reality by creating a false sense of connection to what appears onscreen.

Hallucinations, a side-effect of the “Videodrome” signal, also provide the film’s most potent metaphor. They discharge the idea that exposure to sex and violence in the media is desensitizing or results in an emotionally numb viewer who seeks pleasure through visceral stimuli. In Videodrome, the torturous arena, the experience of watching graphic sex and violence, provides merely the bait for what Spectacular Optical considers social undesirables—it “opens up receptors in the brain and spine”—while the hook resides embedded into any television signal. As Bianca explains, the dangers of “Videodrome” can be hidden inside a test pattern, making television itself the weapon more than any content that appears onscreen, and any viewers subject to enslavement. To another extent, the O’Blivions see television as a social stabilizer, offering TV cubicles in their Cathode Ray Mission where the homeless are reconnected to society through television: “Watching TV will help patch them back into the world’s mixing board.” The weapon is not the brain-washing, brain-scrambling transmission of “Videodrome,” but television itself, which distances the viewer from their sense of reality by creating a false sense of connection to what appears onscreen.

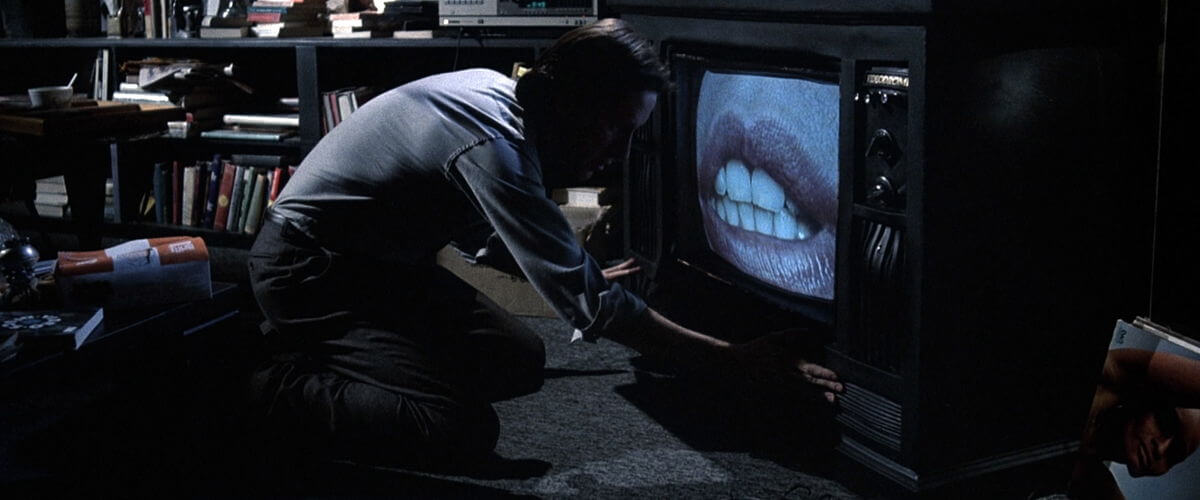

Consider the case of Nicki Brand, who sees “Videodrome” and says she was “made for that show.” Does she mean literally or figuratively? Perhaps she is a televised automaton for Spectacular Optical. Bianca claims, “They used her image to seduce you but she was already dead.” Perhaps Max and Nicki shared but a single encounter when they both appeared on a panel show early in the film, immediately after which Max watches “Videodrome” for the first time. Not until after watching the pirated signal in Harlan’s lab do Max and Nicki meet on any sexual terms, therefore almost her entire appearance onscreen could be an elaborate hallucination. She appears in the torture arena on “Videodrome” later in the film, both when Max is under the control of Spectacular Optical and later as an O’Blivion device, coaxing Max to kill himself to transcend into the “New Flesh.” Perhaps, stimulated by Nicki, Max projects her as an object of desire, employed by his hallucinations as a symbol of stimulation. Then again, her realness may not even matter—as Brian O’Blivion explains: “The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore, the television screen is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore, whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore, television is reality, and reality is less than television.”

In O’Blivion’s cryptic phrasing, he suggests the body exists somewhere between human existence and technological influence, called the “New Flesh.” The body remains in-between two states, and television serves as the “retina of the mind’s eye” that anticipates this relationship. Although the viewer never sees Max fully transformed into his next phase of being, we catch glimpses of bioorganic changes, melting flesh that bends to technology’s influence. The implementation of technology makes the body irrelevant and in some ways abnormal on its own; only through the process of absorbing television does it become normalized, closer to the “New Flesh” of the post-absorption standard—the filter through which any individual must pass to accumulate the information necessary to standardize oneself. Though the process of transition is viewed with horror for its grotesque manipulation of the body, the end result is considered “beautiful” by Cronenberg—a complete, new organism, but one that appears horrifying because it is unfamiliar. To depict this, Cronenberg intended to create a sort of liquid bonding of Max and Nicki’s organic material in the finale, where they would appear together in an unbroken pool of growing and undulating flesh, a melted-together orgy of participants in “Videodrome.” The effect and idea were dropped as Baker could not render the effect to Cronenberg’s liking, leaving much of the audience confused by the New Flesh’s lack of presence in the film. As a result, several allusions to “New Flesh” were cut from the final script.

Though Rick Baker, the effects expert behind the practical makeup for titles like An American Werewolf in London (1981), could not render the abstract concept of the “New Flesh,” his efforts in Videodrome remain a landmark of 1980s make-up effects. As overstimulation is a prevailing theme in the film, it therefore becomes a key factor in Cronenberg’s presentation, leaving Baker and his staff to concoct some of the most disturbing visions ever put to celluloid. From the so-called cancer gun that bonds with Max’s hand and forearm via biomechanical tendrils, to the gun’s bullets that enter Convex and cause his body to surge inside, bursting out with clumps of globulous, cancerous growths, the effects are enough to draw attention away from the director’s considerable overlapping commentaries. The most unforgettable effect remains Max’s stomach slit, which was not meant as an outright vagina, but the image certainly evokes one. It first appears on Max in his apartment, with James Woods’ torso inside a couch prop, connected to the dummy bearer of the slit. This allowed Woods to reach inside the torso and create the illusion that he had penetrated the slit with his hand, which was holding a pistol. The slit seems to swallow the gun. Max panics and the effect advances when Woods stands, reaching inside himself to locate the weapon, his hand pressed against his stomach and covered by a prosthetic lip, and nothing behind the actor to disguise the effect.

Though Rick Baker, the effects expert behind the practical makeup for titles like An American Werewolf in London (1981), could not render the abstract concept of the “New Flesh,” his efforts in Videodrome remain a landmark of 1980s make-up effects. As overstimulation is a prevailing theme in the film, it therefore becomes a key factor in Cronenberg’s presentation, leaving Baker and his staff to concoct some of the most disturbing visions ever put to celluloid. From the so-called cancer gun that bonds with Max’s hand and forearm via biomechanical tendrils, to the gun’s bullets that enter Convex and cause his body to surge inside, bursting out with clumps of globulous, cancerous growths, the effects are enough to draw attention away from the director’s considerable overlapping commentaries. The most unforgettable effect remains Max’s stomach slit, which was not meant as an outright vagina, but the image certainly evokes one. It first appears on Max in his apartment, with James Woods’ torso inside a couch prop, connected to the dummy bearer of the slit. This allowed Woods to reach inside the torso and create the illusion that he had penetrated the slit with his hand, which was holding a pistol. The slit seems to swallow the gun. Max panics and the effect advances when Woods stands, reaching inside himself to locate the weapon, his hand pressed against his stomach and covered by a prosthetic lip, and nothing behind the actor to disguise the effect.

Imagery with powerful connections to sadomasochism and sheer horror is designed to incite an equally powerful reaction, whether imagined by Cronenberg, realized by Baker, or implemented by Michael Lennick, supervisor of the jarring video effects throughout the film. The highly sexual element underscoring violent and ghastly imagery has led to a number of misinterpretations of the film. Critics like Robin Wood have suggested Cronenberg displays disgust with the body, specifically the female body, as he puts it through such torturous imagery and gory transformations. But Wood could not be more wrong. The organic splendor of the director’s imagery eludes Wood, as does the biological rationales behind its origins and eventual emergence. Cronenberg hardly represses the body through disapproval; quite the opposite: he celebrates the body by liberating it from the constraints of standardized Nature, allowing the body to represent both the cerebral and the physical in a single manifestation. Though Cronenberg’s work has sometimes been viewed as sexist, the director would argue his point of view is that of a heterosexual male auteur who values his sexuality. Value judgments are forced on him when critics see sexism in his work, but he creates characters that represent a single individual, not all individuals—stories about a single man or woman, not all men or women. Moreover, Cronenberg’s work remains intriguing because he avoids making films with direct implications capable of only one reading; rather, his work contains imagery and narratives that incite varied reactions, resulting in a body of work that never fails to stimulate discussion and debate.

The dangerous suggestion propelled by Videodrome elucidates Cronenberg’s career-long theory that horror comes from within, rather than external sources such as a masked killer or some awful monster. In the case of the media, Cronenberg would argue that television does not influence viewers, but viewers allows themselves to be influenced through an unconscious choice; therefore, television is not inherently dangerous, though the same cannot be said for home viewers. When censured for purveying socially irresponsible material on Civic TV, Max Renn argues that he provides a healthy outlet: “Better on TV than in the street.” And yet, other forces in the film use television as a weapon or social regulator to take advantage of viewers’ dependence on TV. Spectacular Optical preys on certain viewers by transmitting the “Videodrome” signal in excessively violent or sexual programs; the O’Blivions use television to reincorporate the homeless back into the societal collective. Both institutions wield television to manipulate viewers who allow themselves to be controlled—whether they are amalgamated into slaves or worker bees, or dissolved into the anonymous whole of media consumers (the “New Flesh”).

In true science-fiction form, Cronenberg’s attack on media culture was ahead of its time in 1983, in that it both anticipates technological advances still emerging today and outlines the broad strokes of the director’s ongoing themes. Videodrome proves weirdly precise in its predictions of our increasing dependence on “entertainment” to provide a collective normalcy by which society measures itself. The film anticipates the coming technologies of virtual reality, the return of 3D, and the trend of videogames becoming more user-involved (a theme addressed with more specificity in eXistenZ). Likewise, our dependence on mobile devices easily clipped into the ear or never far from our side, rendering us into near-cyborgs, has never been more apparent. Videodrome also prefigures themes exploring the consequences of new technology, as Cronenberg explored later with The Fly (1986) and eXistenZ, and it accomplishes a narrative set largely in the mind of his protagonist, not unlike Naked Lunch or Spider (2002). He also presupposes films of a similar reality-questioning genre such as The Matrix (1999), and even similarly themed critiques of advances in social relations like that in The Social Network (2010).

In true science-fiction form, Cronenberg’s attack on media culture was ahead of its time in 1983, in that it both anticipates technological advances still emerging today and outlines the broad strokes of the director’s ongoing themes. Videodrome proves weirdly precise in its predictions of our increasing dependence on “entertainment” to provide a collective normalcy by which society measures itself. The film anticipates the coming technologies of virtual reality, the return of 3D, and the trend of videogames becoming more user-involved (a theme addressed with more specificity in eXistenZ). Likewise, our dependence on mobile devices easily clipped into the ear or never far from our side, rendering us into near-cyborgs, has never been more apparent. Videodrome also prefigures themes exploring the consequences of new technology, as Cronenberg explored later with The Fly (1986) and eXistenZ, and it accomplishes a narrative set largely in the mind of his protagonist, not unlike Naked Lunch or Spider (2002). He also presupposes films of a similar reality-questioning genre such as The Matrix (1999), and even similarly themed critiques of advances in social relations like that in The Social Network (2010).

To claim one has total understanding of every shifting reality contained within Videodrome would be misleading, even impossible. Some characters appear only on television screens, while others watch television only to become drones. Who among them is real? Just keeping track of reality in the film remains a challenge as the story progresses, with Cronenberg himself distorting the lines between hallucination and narrative to evoke messages that can oftentimes feel mixed. Martin Scorsese said, “David himself doesn’t know what his films are about.” But with visuals of anthropomorphized televisions and videocassettes, scenes flowing in and out of hallucinations, and imagery wrought with sadomasochistic undertones, the film embraces the multiple meanings of “disorder” to emphasize themes of overstimulation. More an organic pulsation of ideas than a clear explication, Cronenberg’s film suggests that TV reaches out for its audience, making public life in the flesh feel less “real” than our private relationship with the television. Once audiences are infected by the video arena, they question the authenticity of reality and their responses to it, and therein lies the challenge within Videodrome.

Bibliography:

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, c2006.

Mark Browning. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Bristol; London: Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Edited by Chris Rodley. London; Boston: Faber and Faber, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review