The Definitives

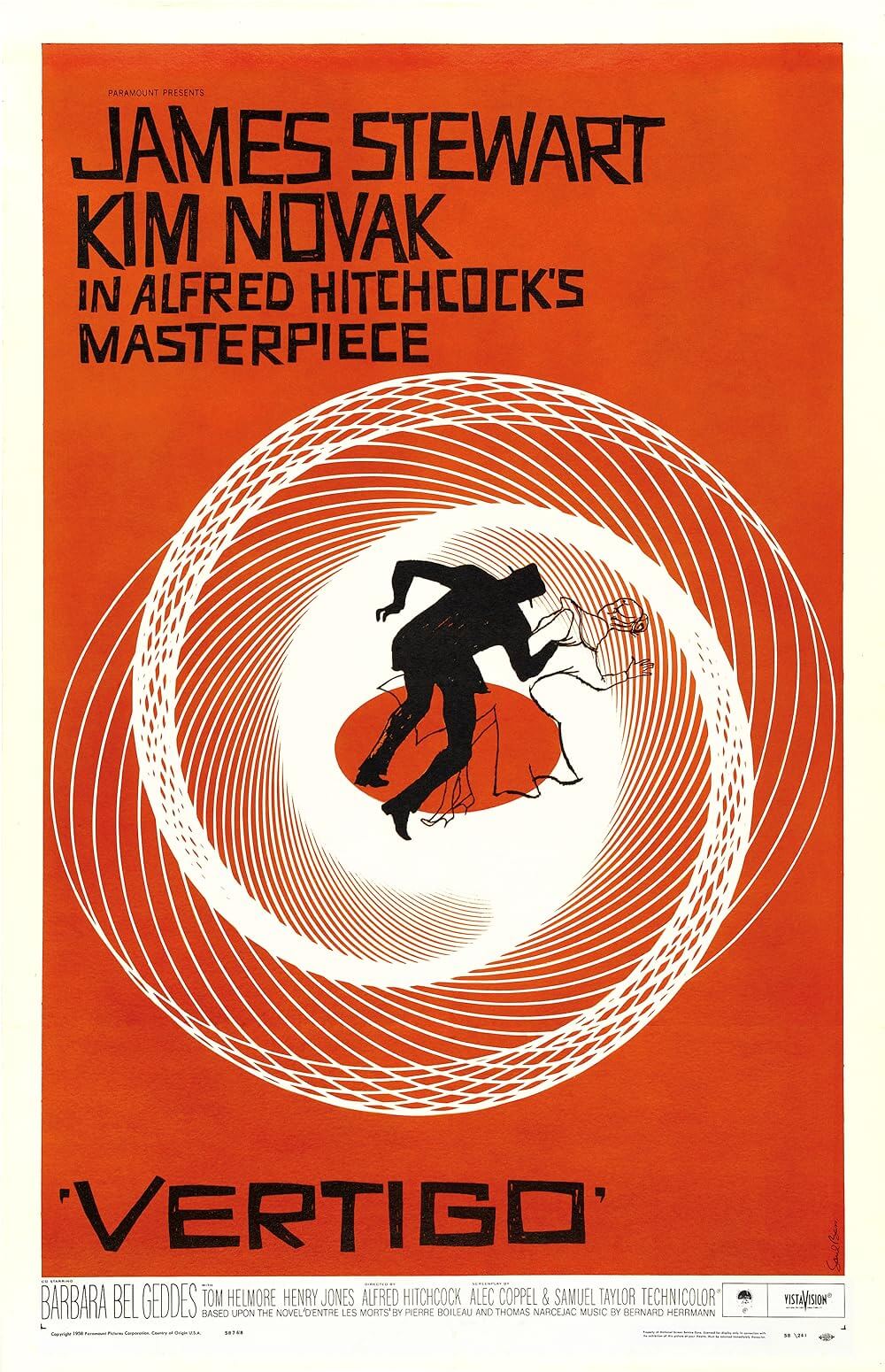

Vertigo (1958)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The director presides over a film, overseeing the creative flow of motion picture production. Savoring his control and minimizing the collaborative aspects of filmmaking, Alfred Hitchcock relished the power of his position in the director’s chair and, according to Hollywood lore, implemented that power through intense previsualization. Every detail of his given project—from storyboards informing both shot composition and editing to the screenplay, which was sometimes perfected over several years—underwent preplanning that rendered actors mere components of his master plan, the blueprint script. Adverse to Orson Welles’ suggestion that a director merely supervises chaos, Hitchcock’s place in film history, though decidedly mythical, exists as the artist of grand design, obsessively imprinting his dogged authority into every facet of the production. This is never more apparent than in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, a film about obsession that offers, as biographical evidence, an outline of the filmmaker’s thematic and personal sexual fixations within its narrative. None of Hitchcock’s many masterpieces so outwardly contemplates the director’s own proclivity to dominate every cinematic element he believed crucial. Mirroring Hitchcock himself through narrative reflectivity, Vertigo is his most personal work, describing his use of, confusion toward, and desperate attempts to control women and their sexuality.

The film encompasses Hitchcock’s reoccurring, albeit arguably unconscious, voyeuristic preoccupations, exposing them from their lingering status in the subtext to confront the viewer with their manifest presence, as well as their underlining position throughout the auteur’s entire oeuvre. Based on the novel D’entre les morts (“From Among the Dead”) by French authors Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, Vertigo was written in hopes that Hitchcock would adapt the story to film. The authors penned a number of novels under those same hopes, though D’entre les morts was their sole success in this regard. Hitchcock attempted to option Boileau and Nercejac’s Les Diaboliques, but French filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot (The Wages of Fear) adapted the project first into the shocking 1955 thriller. Both books harbor themes of ghostly apparitions that eventually reveal themselves in grounded reality, specifically elaborate schemes to get away with murder. But rather than adapt the very French, ethereal story, Hitchcock and writers Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor embedded the director’s own psychological and sexual underpinnings.

The story begins with Det. John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) pursuing a crook across San Francisco rooftops in the film’s jarring first scene. Jumping from building to building, beat cops trailing behind, Scottie leaps short, leaving him clinging to the gutter and dangling high above an alleyway. Another officer attempts to pull him up, but Scottie inadvertently causes the bluecoat to fall to his death. After the incident, Scottie retires, stricken with sudden acrophobia (fear of heights); his close friend and ex-sweetheart Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes) helps him manage his fear, albeit ineffectively. Out of the past, former college acquaintance Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) asks Scottie to shadow his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), believing her moderately deranged and under the delusion that she is the reincarnation of suicide case Carlotta Valdes. Accepting the assignment with some reservations, Scottie trails Elster’s wife and, in the process, slowly falls in love with her. Madeleine drives about the rise and fall of San Francisco’s city streets, stops at the Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum to view Portrait of Carlotta, and takes a brief respite in Carlotta’s former home. Scottie follows close behind, and he eventually makes contact and rescues Madeleine when she attempts to drown herself in San Francisco Bay. The next day, the two meet again on romantic terms, Madeleine unaware that Scottie was hired by her husband to spy. Despite their mutual love, Scottie cannot break Madeleine’s apparent possession by Carlotta. After she remembers a past life event at Mission San Juan Bautista, Scottie takes her there. She races up the steeple and leaps to her death, with Scottie, gripped by his acrophobia, powerless to stop her.

The story begins with Det. John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) pursuing a crook across San Francisco rooftops in the film’s jarring first scene. Jumping from building to building, beat cops trailing behind, Scottie leaps short, leaving him clinging to the gutter and dangling high above an alleyway. Another officer attempts to pull him up, but Scottie inadvertently causes the bluecoat to fall to his death. After the incident, Scottie retires, stricken with sudden acrophobia (fear of heights); his close friend and ex-sweetheart Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes) helps him manage his fear, albeit ineffectively. Out of the past, former college acquaintance Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) asks Scottie to shadow his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), believing her moderately deranged and under the delusion that she is the reincarnation of suicide case Carlotta Valdes. Accepting the assignment with some reservations, Scottie trails Elster’s wife and, in the process, slowly falls in love with her. Madeleine drives about the rise and fall of San Francisco’s city streets, stops at the Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum to view Portrait of Carlotta, and takes a brief respite in Carlotta’s former home. Scottie follows close behind, and he eventually makes contact and rescues Madeleine when she attempts to drown herself in San Francisco Bay. The next day, the two meet again on romantic terms, Madeleine unaware that Scottie was hired by her husband to spy. Despite their mutual love, Scottie cannot break Madeleine’s apparent possession by Carlotta. After she remembers a past life event at Mission San Juan Bautista, Scottie takes her there. She races up the steeple and leaps to her death, with Scottie, gripped by his acrophobia, powerless to stop her.

Suffering “acute melancholia together with a guilt complex,” Scottie endures a nervous breakdown after Madeleine’s death, recovering with the motherly support of Midge by his side. Sometime later, on the street, he comes across Judy Barton (also Kim Novak), a dead ringer for Madeleine who claims to know nothing of either Scottie or his former love. In a fog over her similarities to Madeleine, Scottie courts Judy, unaware that she is indeed Madeleine, or rather a piece in an elaborate plot conceived by Gavin Elster to murder his wife using a double, intending Scottie to witness Madeleine’s faux suicide. Now back to her proper identity, Judy, formerly Elster’s mistress, finds Scottie’s attachment to Madeleine’s memory tragic since her love for Scottie, even while role-playing, was genuine. However, Scottie’s passions exist for Madeleine alone, and his attraction to Judy is more of a fascination with her uncanny resemblance. He proceeds to reshape Judy according to the haunting figure in his memory, hoping to make her appear as Madeleine so he may once again hold his love. At first, Judy protests, knowing that Scottie clings to a false notion, desperate for Scottie to love her as Judy, not an ersatz version of herself. He buys Judy the same gray suit worn by Madeleine, indicates precise makeup application, dyes her hair blonde, and then demands that she style it a specific way: the Madeleine way. A boutique attendant rightly observes, “The gentleman seems to know what he wants.” When Judy’s makeover is complete, she materializes as Madeleine exactly.

All at once, Scottie suspects that Judy is, in fact, Madeleine when she carelessly puts on Carlotta’s necklace, an extravagant keepsake from her crime and signifier that a horrible hoax was arranged to deceive him. To elicit a confession, he drives Judy to the mission where Madeleine died, forcing her up the steeple where his focused anger gradually dissolves his acrophobia. Judy admits to her part in Elster’s ruse, how Elster killed his wife and made it appear like suicide, and how she willfully posed as Madeleine and seduced Scottie. As she confesses, she trips and plummets to her death, falling out the same window from which Elster’s wife was thrown. Scottie looks over the edge, healed of his fear, shattered with heartbreak.

Vertigo’s subject dwells in the self-destruction inherent to obsession, which the title likens to Scottie’s fear of heights, a metaphor for his fear of plummeting into love. In the complex relationships between Scottie and Judy, and Scottie and Midge, the protagonist resists contentment and instead hopes for an unattainable ideal—a woman that never existed, that was a fantasy constructed to seduce him. Scottie’s apparent madness, as he heartlessly molds Judy into Madeleine with a fetishist’s eye for clothing and makeup, detaches some devoted Hitchcock fans. As the saying goes, there are two categories of Hitchcock aficionados: those who love Vertigo and those who do not. Scottie’s unsympathetic, alarming behavior confronts moviegoers in the film’s dramatized tragedy; participants must endure a wholly rational character, portrayed by America’s genial everyman James Stewart, deteriorate into an irrational victim of his own desire. “There’s an answer for everything,” Scottie tells Madeleine, affirming his detective’s sense of examining clues objectively to determine a rational explanation. And yet, he falls frantically and irrationally in love with Madeleine, a married woman, and his mark no less.

Why not fall for Midge, the readily available and good-hearted woman by Scottie’s side in friendship? Not included in D’entre les morts, her character was added by Hitchcock to demonstrate the senselessness of man’s search for love, to show that he does not supremely search for a replacement mother like Freudian theory suggests, but instead longs for his mother’s sexual opposite. Scottie rejects Midge sexually, referring to her as “mother” on several occasions, whereas Madeline remains subject to his increasing scopophilia. Midge places herself in the maternal position; after his breakdown, she consoles him saying, “You’re not lost, mother’s here.” He denies or overlooks Midge, preferring the fantasy. Even the name, Midge, is brutal and short and motherly, whereas Madeleine rolls from the tongue like a song. Moreover, Midge designs women’s undergarments, and in the scene following Scottie’s roof chase accident, Scottie eyes one of her bras and asks, “What’s this doohickey?” Midge responds, “It’s a brassiere. You know about those things, you’re a big boy now.” In her hands, however, the item is broken down into schematics and pencil designs, its sexuality removed in hopes of providing a “revolutionary up-lift.” Conversely, Hitchcock told François Truffaut that Kim Novak was proud that she wears no bra at all, thinking it symbolic that her characters’ sexual Selves are liberated from such constraint.

Why not fall for Midge, the readily available and good-hearted woman by Scottie’s side in friendship? Not included in D’entre les morts, her character was added by Hitchcock to demonstrate the senselessness of man’s search for love, to show that he does not supremely search for a replacement mother like Freudian theory suggests, but instead longs for his mother’s sexual opposite. Scottie rejects Midge sexually, referring to her as “mother” on several occasions, whereas Madeline remains subject to his increasing scopophilia. Midge places herself in the maternal position; after his breakdown, she consoles him saying, “You’re not lost, mother’s here.” He denies or overlooks Midge, preferring the fantasy. Even the name, Midge, is brutal and short and motherly, whereas Madeleine rolls from the tongue like a song. Moreover, Midge designs women’s undergarments, and in the scene following Scottie’s roof chase accident, Scottie eyes one of her bras and asks, “What’s this doohickey?” Midge responds, “It’s a brassiere. You know about those things, you’re a big boy now.” In her hands, however, the item is broken down into schematics and pencil designs, its sexuality removed in hopes of providing a “revolutionary up-lift.” Conversely, Hitchcock told François Truffaut that Kim Novak was proud that she wears no bra at all, thinking it symbolic that her characters’ sexual Selves are liberated from such constraint.

One of Vertigo’s most difficult scenes entails Scottie arriving at Midge’s home after she left a note under his door asking, “Where are you?” Following Madeleine, little time is left over for Midge and, frantic to keep Scottie to herself and not lose him to the fantasy of Madeleine, she makes a desperate move: she shows Scottie her painting that accurately recreates Portrait of Carlotta, except with her own head inserted onto the body. With the painting, she shows Scottie that she too can be sexual, and jealous, and literally illustrates that she wants to be the focal point of Scottie’s obsession. It angers him. He prefers Madeline’s outright visual sexuality, not the inferred sexuality of Midge. Leaving, he can only resignedly say “No” repeatedly, while Midge curses herself for risking it all and losing.

For Scottie, acquiring his ideal woman equates to a highwire act wherein he fears ultimately falling to his death, but nevertheless, places himself into harm’s way for both pre- and post-suicide Madeleine. In the extended sequence where Scottie follows Madeleine in her car, a dizzying section of road sends him downhill on the literal downward spiraling streets of San Francisco. After her death and his recovery from catatonia, he mistakenly sees Madeleines at the art museum, in a restaurant, and in her old car. Roger Ebert asks if Scottie simply desires another sample from the cookie jar, asking, “Is it a coincidence that the woman is named Madeleine—the word for the French biscuit, which, in Proust, brings childhood memories of loss and longing flooding back?” Allusions to dessert aside, consider Scottie fraught with controlling that which he does not understand, specifically Madeleine, an embodiment of his own romantic fantasy and, therefore, a piece to understanding himself. Why does anyone pursue a lover, if not to improve or find the best version of themselves?

Guilt-ridden after causing the death of a fellow policeman, unconsciously, Scottie prefers escape over reality by focusing his energy on a flawless projection, something dreamy, something perfect. Of course, no such ideal exists until Elster instructs Judy on how to become that ideal. When Scottie later confronts Judy, he talks through how Elster must have plotted, sounding more jealous than betrayed: “You played the wife very well, Judy. He made you over, didn’t he? He made you over just like I made you over. Only better. Not only the clothes and the hair, but the looks and the manner and the words. And those beautiful phony trances. And you jumped into the Bay! I bet you’re a wonderful swimmer, aren’t you… aren’t you… Aren’t you! And then what did he do? Did he train you? Did he rehearse you? Did he tell you exactly what to do and what to say? You were a very apt pupil, weren’t you? You were a very apt pupil!” What Scottie seems to resent most is the question raised about his masculinity, in that Elster made Judy up like Scottie “only better,” and so Elster is the better man. Tania Modleski argues in her book The Women Who Knew Too Much that instinctively, man searches for a female counterpart to better understand himself, using the woman as a mirror. For Scottie, that mirror does not exist; instead, it exists as an artificial statuette, leaving him in a state of confused self-understanding and challenging his manhood.

Guilt-ridden after causing the death of a fellow policeman, unconsciously, Scottie prefers escape over reality by focusing his energy on a flawless projection, something dreamy, something perfect. Of course, no such ideal exists until Elster instructs Judy on how to become that ideal. When Scottie later confronts Judy, he talks through how Elster must have plotted, sounding more jealous than betrayed: “You played the wife very well, Judy. He made you over, didn’t he? He made you over just like I made you over. Only better. Not only the clothes and the hair, but the looks and the manner and the words. And those beautiful phony trances. And you jumped into the Bay! I bet you’re a wonderful swimmer, aren’t you… aren’t you… Aren’t you! And then what did he do? Did he train you? Did he rehearse you? Did he tell you exactly what to do and what to say? You were a very apt pupil, weren’t you? You were a very apt pupil!” What Scottie seems to resent most is the question raised about his masculinity, in that Elster made Judy up like Scottie “only better,” and so Elster is the better man. Tania Modleski argues in her book The Women Who Knew Too Much that instinctively, man searches for a female counterpart to better understand himself, using the woman as a mirror. For Scottie, that mirror does not exist; instead, it exists as an artificial statuette, leaving him in a state of confused self-understanding and challenging his manhood.

Hitchcock devises the entire presentation of Vertigo without observance of traditional verisimilitude, applying formal techniques that place Scottie within a false world throughout the film, emphasizing the character’s blurred self-identity. Preferring the controlled environment of an elaborately designed studio set versus the unpredictability of location shooting, Hitchcock uncharacteristically uses several process shots, an effect where backgrounds are filmed on a separate reel from the characters inhabiting them. His intentional choice renders sections of the film obvious fabrications, conceived without his standard, unblemished use of believable mise-en-scéne. Furthermore, nearly every scene was photographed through filters, primary color hues, and soft light, lending a haze that illustrates the film’s atmospheric narrative. Even Madeleine, the film’s idyllic vision of sexual desire, is put forward as a vague figure donning gray clothes, aloof from her supposed possession, wraithlike, her ponderous and removed disposition uncertain.

Perhaps the mystery-laden circumstances and Madeleine’s dreamlike persona bewilder Scottie, and after he witnesses her “suicide,” her intangibility causes his persistent infatuation and subsequent mental trauma. Consider the dreamy look of the scene where Judy finally emerges, made over like Madeleine, and Scottie takes her in his arms unreservedly. The room is filled with an unearthly green light from the hotel’s neon sign, glowing and hallucinatory. Hitchcock’s camera orbits the pair locked in a passionate kiss, the hotel background dissolving into Scottie’s memory of he and Madeline’s first embrace and then back again. Imprisoned by his memories of a fantastical love, according to Hitchcock, “[Scottie] wants to go to bed with a woman who’s dead; he is indulging in a form of necrophilia.” The director’s remark has forever transformed this tender scene into something horrifying.

While the first half of Vertigo involves Scottie and his search for self-understanding through romantic discovery, a changeover occurs when the third act discloses Judy’s secret to the audience, but not Scottie, in the narrated writing of her confession. Having just spotted Judy for the first time on the street, Scottie follows her to her apartment door. The audience has seen Scottie mistake women for Madeleine before by this point, but Judy is the first interaction. She pities him and agrees to dinner, asking him to return in an hour. When alone again, Judy begins to prepare for an apparent getaway; she sits down to write a letter explaining Elster’s plot and her role therein, that the Madeleine of Scottie’s heartbreak never existed. But then, perhaps in consideration of her love for Scottie and the hope that she can make him love her as Judy, she tosses the letter away, leaving the audience with crucial information about Scottie’s story. Perspectives change: the audience shifts from identifying with Scottie’s lovelorn misfortune and melancholia to concern about what will happen to Judy when Scottie discovers her secret. Aligning with Scottie until the flashback, the film remains subjectively male but then takes a radical transfer to an accelerated feminine, almost bisexual subjectivity when the audience is asked to consider both Scottie’s desire and, in perhaps the ultimate staging of dramatic irony, Judy’s secret. Her male-afflicted victimization and visual objectification by way of Scottie’s manic insistence that she changes her appearance to suit his needs realigns our sympathy. The viewer fears Scottie’s reactions and cannot empathize with them in his disturbed and possessed form. So empathy is cleverly directed toward Judy, who, knowing what the audience knows, always appears in unbearable pain, hiding her love and sacrificing her dignity for Scottie.

Hitchcock’s choice to include the scene of Judy’s written confession was last-minute and almost found its home on the cutting room floor. Except, as Patrick McGilligan argues in Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, the director’s wife, Alma Reville, the frequent credited and ghostwriter of Hitchcock scripts, vied for its placement. She recognized that without it, the audience’s empathy for Scottie mutates into confusion and inability to relate to a troubled mind. Included, the letter scene helps identify with the sympathetic female psyche, and in that, shapes Scottie into an almost antagonist role. Not only does this protagonist switch challenge the audience’s sense of linear drama, but the choice represents the epitome of Hitchcockian suspense trickery: Hitchcock swaps out one hero for another, deems the first capable of murder or worse, ends the madness with the new lead’s shocking death, and then leaves the audience to soak up the tragedy.

Hitchcock’s place was The Director’s Chair, where he reveled in the power to upset the ordinary, to create suspense, and to manipulate audience involvement. Disturbing normality was his pleasure as an auteur. In another of his many masterpieces, Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Hitchcock introduces a cold-blooded killer, played by Joseph Cotton, into middle-class suburbia, a neighborhood lined with white picket fences and little girls with bows in their hair; he even suggests murderers might exist within the average American family. Finding the splotch on the whitewashed canvas was his specialty. Hitchcock set his stories in iconic locations and struck the macabre into the ordinary, blotting America’s comfortable landscapes with a murderous twist: Vertigo has the Golden Gate Bridge, Saboteur (1942) has the Statue of Liberty, and North by Northwest (1959) has Mount Rushmore. His formula was to disrupt knowing into a state of unknowing, allow his audience to catch their breath, and then disrupt some more, controlling every instrument in his orchestra with a precisely arranged crescendo.

Hitchcock’s control myth, the idea that he was the solitary creative mind on set, resolves that everything the audience sees on screen was preconceived prior to filming. Many who worked with Hitchcock, and indeed the director himself, outlandishly claimed that he was never on set and, if present, slept in his director’s chair. Depicted as a tyrannical preproduction ruler, Hitchcock ensured that, by the time cameras began to roll, the entire film had been schematized; therefore, his being there was pointless. The truth, of course, was much different. Though Hitchcock’s supposed method resides within efficient adherence to the script and storyboards, a film set where budgetary concerns crop up, equipment breaks down, and improvisation occurs daily rarely allows for this. While Hitchcock sought less on-set improvisation than most directors, reports of his obsessive preplanning techniques are undoubtedly exaggerated.

Hitchcock’s control myth, the idea that he was the solitary creative mind on set, resolves that everything the audience sees on screen was preconceived prior to filming. Many who worked with Hitchcock, and indeed the director himself, outlandishly claimed that he was never on set and, if present, slept in his director’s chair. Depicted as a tyrannical preproduction ruler, Hitchcock ensured that, by the time cameras began to roll, the entire film had been schematized; therefore, his being there was pointless. The truth, of course, was much different. Though Hitchcock’s supposed method resides within efficient adherence to the script and storyboards, a film set where budgetary concerns crop up, equipment breaks down, and improvisation occurs daily rarely allows for this. While Hitchcock sought less on-set improvisation than most directors, reports of his obsessive preplanning techniques are undoubtedly exaggerated.

Instead, consider this myth an ideal approach employed when possible, enabled in part for Hollywood publicity to advertise their director for the first time. His popularity spawned from the success of the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, without his commercial viability, it is doubtful Hitchcock could have made such a personal film as Vertigo in 1958. Hitchcock engrossed himself in whatever his current project may have been, some more than others, sometimes reaching the extreme of infatuation, attuning finer details according to his own predominant tastes. Performers, particularly his actresses, were chosen according to his desires. Soundstages were regularly used to craft and thus regulate his vision. His status as a legend, birthed from the embellished and conflicting accounts about his method, holds considerable legitimacy.

The production of Vertigo allowed one technical obsession of Hitchcock’s to flourish by way of his innovational artistry. The director had long-envisioned the type of camera effect needed to convey disorientation, in this case, Scottie’s “vertigo”, but technology could not yet construct his mental picture. Plagued by the idea since making his first American production for David O. Selznick, the Best Picture Academy Award winner Rebecca (1940), he was told the effect cost too much to produce. But he insisted on this point-of-view shot from Scottie’s perspective, so technicians employed cheaper miniatures of the steep stairway and alley that caused the character’s breakdowns. By zooming the lens inward and increasing its focal length while dollying the camera out at the same time, the resulting effect leaves the viewer with an intended unsteadiness (and also suggests to Freudian theorists that the in-out motion infers Hitchcock’s sexual preoccupation with the effect). Though copied by directors ranging from Brian DePalma to Steven Spielberg, their uses have been in the name of superfluous homage to its original; never has its application been given such powerful consequence to the narrative as in Vertigo.

The singular film remains vital to understanding the confused psychology of Hitchcock, above all his sexual identity. Hitchcock claimed the only time he and his wife Alma engaged in intercourse was to conceive their daughter, Patricia, and his biographers believe the resultant sexual repression caused a late-life disorder and unaddressed fixations. His films were thus embedded with a symbolic and subtextual curiosity to investigate topics of an unconsciously sexual nature. His filmography contains several cold, inaccessible women characters, usually blonde, designed with equal parts style and fetishism. Hitchcock’s leading ladies were often humiliated, placed in danger, or altogether murdered (on screen) in what scholars attribute to Hitchcock’s desperation to understand and thus conquer the unknown female.

Like Scottie’s attempts to understand the dreamlike nature of Madeleine, Hitchcock pursued this mystery by way of his cinematic tools of narrative and formal presentation, enriching his pictures with sexualized undertones and visual bravado. Knowingly ornamenting his pictures with innuendo, he did not confront his own psychological relationship with women on film until Vertigo and further revealed his possessive and unhealthy associations in the subsequent films Marnie (1964) and Frenzy (1972). Perhaps he resented women for what he believed was their lack of genuine reflectivity, as his biographers suggest. Or maybe he considered them impossible to contain or even understand on emotional grounds and thus exerted his directorial prowess unto women he found himself attracted to. On set, he was in absolute control over women under his direction, whereas offset, his personal life was no longer a Hollywood production complete with a director’s chair reading “Mr. Hitchcock.”

All the same, Hitchcock still fought battles with women on set, except without the need for the patience and warmth of a loving husband and father, which he most certainly was. He could be downright cruel on the job, imposing near torturous influence over an actress that displeased him—his treatment of Joan Fontaine and Tippi Hedren being the most extreme cases. His second choice for Madeleine/Judy, Kim Novak was not “meant” to play the role, so her director spurned her from the outset. Hitchcock originally intended to shoot Vera Miles in the role(s), except, much to his annoyance, Miles became pregnant. Such was a reoccurring aggravation with Hitchcock and his leading ladies, as pregnancies and marriages had prevented actresses like Ingrid Bergman and Anita Björk from taking various roles for which Hitchcock believed them ideal. These conflicts escalated if Hitchcock did not approve of his actress’ choice in men. And so, Novak, the replacement for Hitchcock’s original choice of Miles, became subject to his vengeful resentment.

When meeting with legendary costume designer Edith Head to plan her elegant wardrobe for the picture, Novak insisted on anything but gray. Either trying to say that she had not yet read the script or book, both of which describe Madeline’s attire as a gray suit or simply trying to irritate her director, Novak’s gray suit becomes the key attire-based signifier for Madeline in the film, the outfit over which Scottie obsesses so. Hitchcock’s taste was not so much his choice but the requirements of the character, the color of gray alluding to Madeline’s foggy psychology, the varied and uncertain way Hitchcock believed many women see themselves. Novak’s behavior infuriated Hitchcock, so he flexed his authoritarian muscle to belittle Novak into feeling powerless and dependent, dissolving her opposition until she no longer knew her role in the film, which would render perfectly onscreen. Madeline and Judy are multi-faceted personas; each layered with uncertainties, weak façades, and exposed underbellies. Like Scottie, Hitchcock made her up with his very specific choice of clothing; he shaped her behavioral mannerisms, such as how she walked and talked. Hitchcock did all he could to transform Novak into an object of his design, forcing her to evoke the character in front of the camera through the discomfort and alienation he caused the actress offscreen.

Nevertheless, for all the ways Hitchcock identifies with Scottie, the director sees outside himself enough to include the feminine viewpoint by changing the spectatorship from male to female with Judy’s letter. With this device, Hitchcock admits his behavior is at once conscious and cruel but also uncontrollable, impulsive, and perhaps even mad. Vertigo provides a release for themes building throughout his career, allowing Hitchcock to finally work out his longtime obsessions with a kind of cinematic therapy, finally acknowledging their existence to embrace their undeniable presence—their axis upon his work. He infiltrates his own psyche as he explores obsession, finding a complex predatory emotion that encircles its prey. That sense of encircling undoubtedly informed Vertigo’s production, permitting composer Bernard Herrmann and title designer Saul Bass to act upon their respective skills according to the narrative. Herrmann’s score plays on a haunted merry-go-round, shuttered by gratification and melancholy, going around and around with lasting persistence. Saul Bass’ lurid title sequence segments a woman’s face, shifting locations on the anonymous visage like a scopophile examining an enamored thing, and then offers spirals twisting about to demonstrate the rhythmic temperament of obsession.

Deemed his personal “masterpiece” for, in effect, being about Alfred Hitchcock himself, Vertigo, aside from its autobiographical traces, is a motion picture of incomparable dramatic involvement and hypnotic filmmaking. Its characters feel material, yet they exist in a terrifying nightmare of conflicting, deeply tragic duality. So well articulated in every inference, the intricate story and the implications thereof beautify the film’s substance beyond the label of mere suspense, placing the film into the realm of probing psychological art. It takes a particular genius to retain Hitchcock’s clarity of purpose in this investigation, and only a filmmaker with his profound ardor for the topic could escalate his obsessions past the recurrent foreplay of his career and realize them with such cinematic intimacy.

Bibliography:

Krohn, Bill. Hitchcock At Work. Phaidon, 2000.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, c2003.

Modleski, Tania. The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. Routledge, 2006.

Petrie, Graham. Hollywood destinies: European directors in America, 1922-1931. Wayne State University Press, c2002.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. Atheneum, 1975.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Žižek, Slavoj. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). Verso, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review