The Definitives

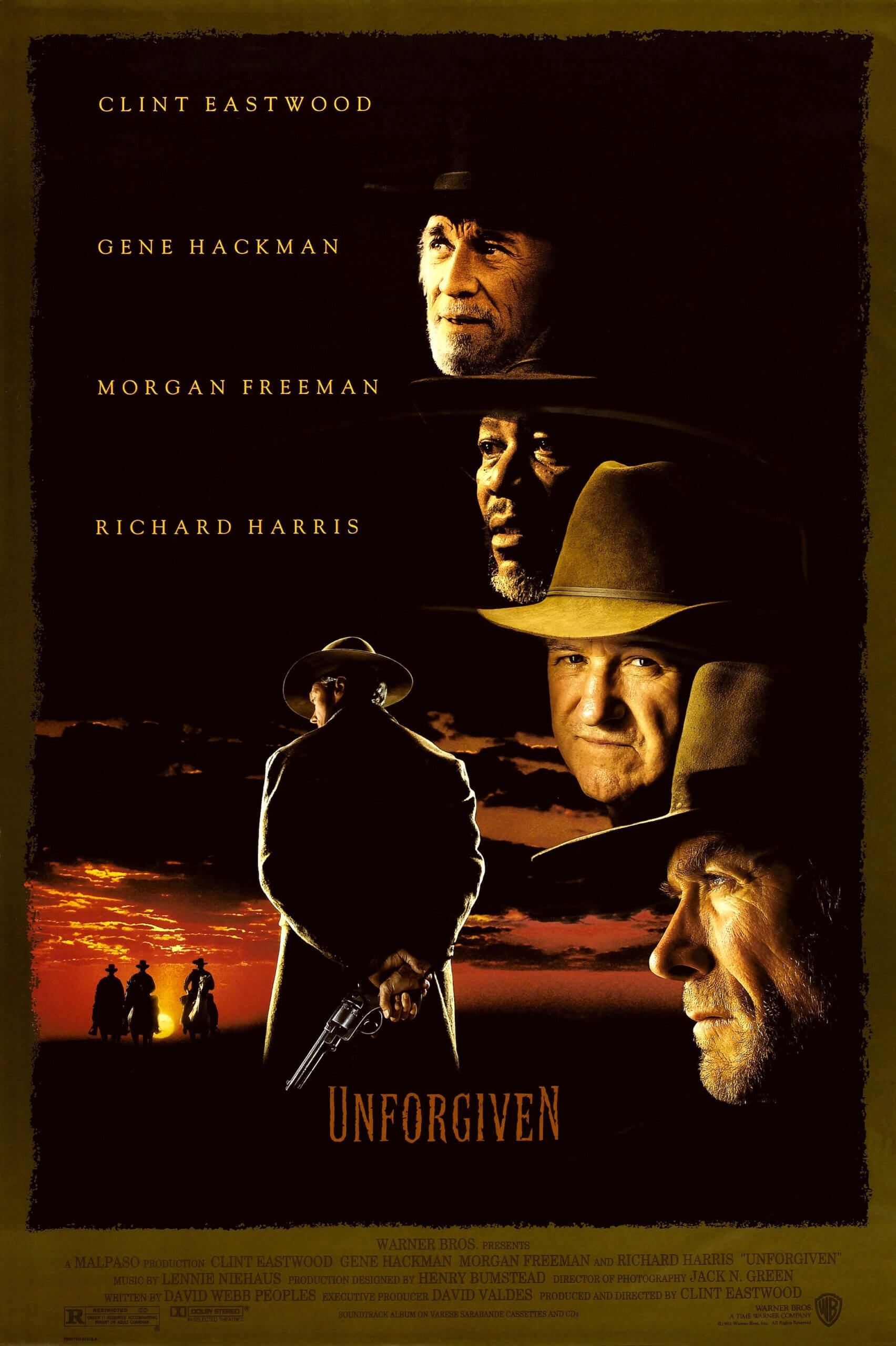

Unforgiven (1992)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

With masterful temperance and humanity, Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven adopts a critical structure to reassess our perception of the American West, both in historical terms and in an autobiographical context for its director, producer, and star. As a revisionist Western reflecting on the past, the film takes place at a time when gunslingers had lived long passed their prime. By 1880, about when the film takes place, these men had eased into what might be called simpler lives. Some escaped the violence of their former selves to settle down with a family, while others celebrated their own names by participating in dime novels and Wild West shows that transformed their exploits into the feats of living legends. Likewise, in 1992, when Unforgiven was released, the larger part of Eastwood’s career as an actor and filmmaker relied on his status as a masculine protagonist in violent, escapist action films where, along with Eastwood himself, characters like Dirty Harry and The Man with No Name became screen icons. With this film, Eastwood redefines his onscreen and offscreen persona by instilling uncertainty into traditional Western archetypes, and in doing so the film questions the history of the American West and furthermore Eastwood’s own role in defining the West in cinema.

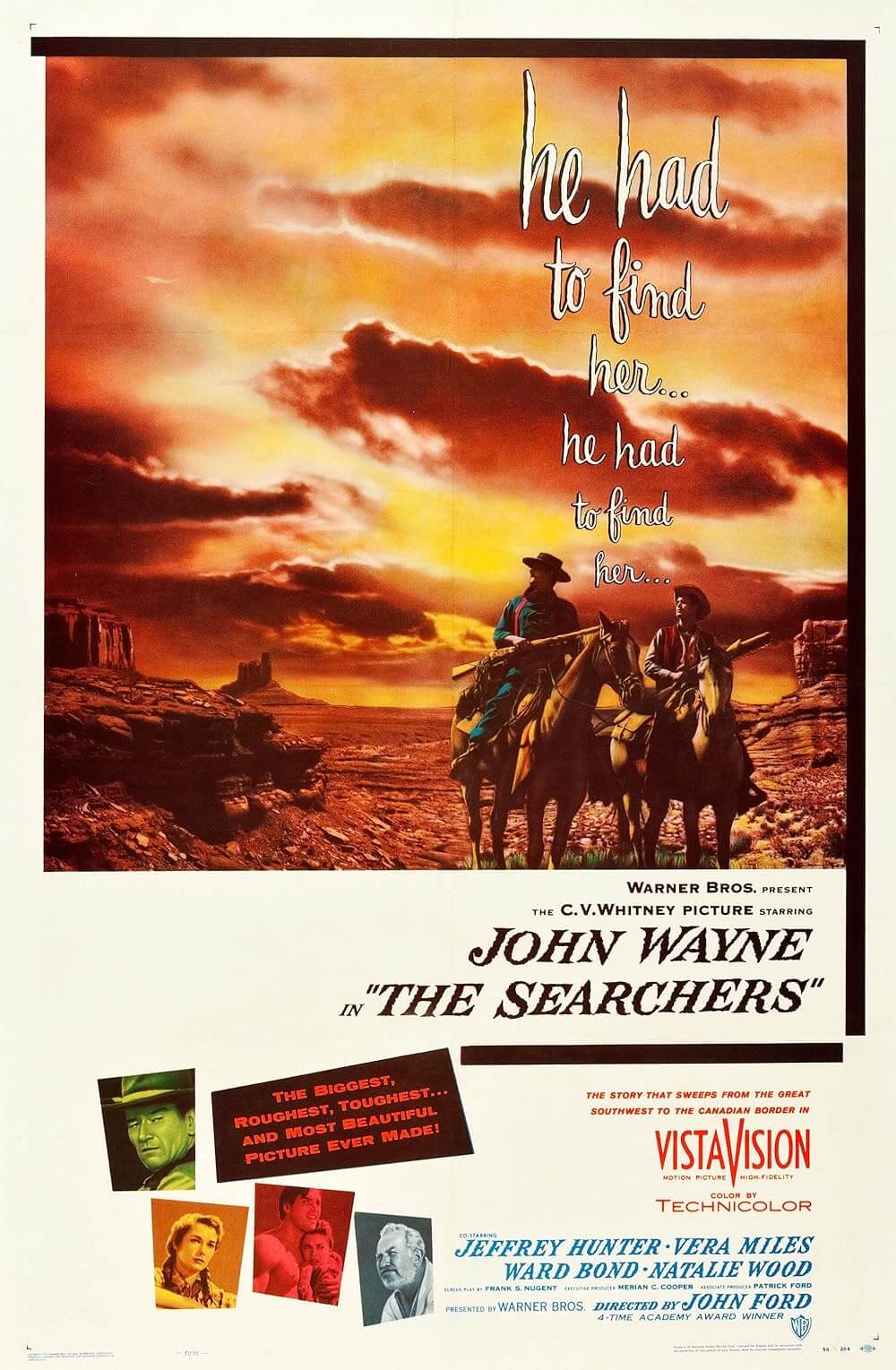

Much as John Ford had done when, after decades of directing classical Westerns like Stagecoach (1939) and My Darling Clementine (1946), Ford released his critique of Hollywood’s treatment of the West in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Eastwood’s film rethinks how we view the Western and, to a greater extent, America. His film questions how we understand a Western hero, how we applaud the hero’s violent ways, and how history is so often exaggerated. And although Eastwood insists his film was not meant to contain an autobiographical commentary, in some respect it does that too. “I’m not doing penance for all the characters in action films I’ve portrayed up till now,” he told an interviewer. True enough, as Eastwood’s provisionally reformed killer William Munny in Unforgiven is not a redeemed man by the film’s conclusion; however, Eastwood’s film complicates its characters enough to suggest that we take a discerning, critical look at our bloody past to comprehend, or at least acknowledge, that our bloody present cannot be so easily defined. As a result, Eastwood’s career can no longer be summed up as the labor of an action star.

Eastwood optioned the screenplay by David Webb Peoples six years prior to its release. The interim passed not because the script needed retooling—Eastwood’s production did not deviate much from Peoples’ script—but because Eastwood sought to make a dramatically relevant picture. Mainstream genre titles like Play Misty for Me (1971), The Gauntlet (1977), and Pale Rider (1985) populated Eastwood’s directorial career until Bird (1988), his meditative arthouse biopic of jazz legend Charlie Parker, starring Forest Whitaker. He followed Bird with White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), where Eastwood played a thinly concealed version of director John Huston, whose African safari became an obsession during the shoot of The African Queen (1951). Even with credible efforts such as Bird and White Hunter, Black Heart having debuted at the Cannes Film Festival, Eastwood returned to a typical shoot-em-up when he directed Charlie Sheen in The Rookie (1990), which was the director’s more common type of film up to this point. In spite of a few rare exceptions, Eastwood’s slow inching away from mainstream fodder culminated with the extraordinary craft on display in Unforgiven, then so unprecedented, marking a turning point for Eastwood as a filmmaker and storyteller.

Eastwood optioned the screenplay by David Webb Peoples six years prior to its release. The interim passed not because the script needed retooling—Eastwood’s production did not deviate much from Peoples’ script—but because Eastwood sought to make a dramatically relevant picture. Mainstream genre titles like Play Misty for Me (1971), The Gauntlet (1977), and Pale Rider (1985) populated Eastwood’s directorial career until Bird (1988), his meditative arthouse biopic of jazz legend Charlie Parker, starring Forest Whitaker. He followed Bird with White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), where Eastwood played a thinly concealed version of director John Huston, whose African safari became an obsession during the shoot of The African Queen (1951). Even with credible efforts such as Bird and White Hunter, Black Heart having debuted at the Cannes Film Festival, Eastwood returned to a typical shoot-em-up when he directed Charlie Sheen in The Rookie (1990), which was the director’s more common type of film up to this point. In spite of a few rare exceptions, Eastwood’s slow inching away from mainstream fodder culminated with the extraordinary craft on display in Unforgiven, then so unprecedented, marking a turning point for Eastwood as a filmmaker and storyteller.

Peoples’ noirish Western story constructs for Eastwood a character who might earn comparisons to the actor’s own cowboy heroes from High Plains Drifter (1973) or The Outlaw Josey Wales (1975), with equal parts myth-making and humanism infused into his role of William Munny, an aged Kansas pig farmer and former gunslinger ten years tamed by his departed wife, Claudia. When the film opens, Munny struggles to raise two children and maintain his farm. We first meet Munny as he and his son attempt to separate feverish hogs from the others and he falls flat on his face in the mud. This is how a rider calling himself the Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett) first sees Munny. The Kid has heard Munny was once a ruthless killer, and he offers to split a bounty if Munny will ride with him. “I ain’t like that anymore, Kid. It was whiskey done it as much as anythin’ else. I ain’t had a drop in over 10 years. My wife, she cured me of that, cured me of drink and wickedness.” Munny’s children look on bewildered. “Did Pa used to kill folks?”

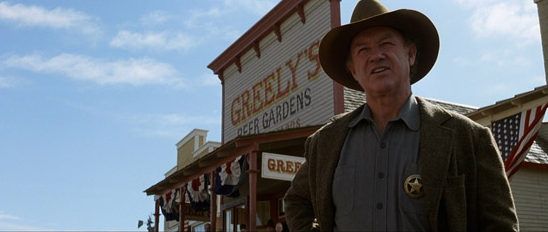

Traditional Westerns often feature a woman in peril who must be rescued by the hero, and indeed this film features several women calling for the aid of a gunslinger, but rather than an innocent schoolmarm that represents civilized society (as in My Darling Clementine), the women whose honor has been insulted are whores in a “billiards” hall in the small town of Big Whiskey, Wyoming. One night, two cowboys—Quick Mike (David Mucci) and Davey Bunting (Rob Campbell)—slash the face of Delilah (Anna Levine), a prostitute, after she snickered at Quick Mike’s “teensy little pecker”. The local sheriff, Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman), was once a gunslinger himself but now jealously keeps the peace in his town. Little Bill agrees to let the cowboys go and fines the offenders several horses on behalf of pimp Skinny Dubois (Anthony James). When the cowboys return with payment, Delilah, whose face now bears several scars, seems touched and nearly bound to forgiveness when the younger Davey offers his best pony not to Skinny but to his partner’s victim. Nevertheless, Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), the girls’ leader, wants blood. She pools together the girls’ savings to offer $1,000 to anyone who kills the two cowboys. For Little Bill, this means unsavory types, assassins, and gunslingers will arrive in his otherwise peaceful town.

Traditional Westerns often feature a woman in peril who must be rescued by the hero, and indeed this film features several women calling for the aid of a gunslinger, but rather than an innocent schoolmarm that represents civilized society (as in My Darling Clementine), the women whose honor has been insulted are whores in a “billiards” hall in the small town of Big Whiskey, Wyoming. One night, two cowboys—Quick Mike (David Mucci) and Davey Bunting (Rob Campbell)—slash the face of Delilah (Anna Levine), a prostitute, after she snickered at Quick Mike’s “teensy little pecker”. The local sheriff, Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman), was once a gunslinger himself but now jealously keeps the peace in his town. Little Bill agrees to let the cowboys go and fines the offenders several horses on behalf of pimp Skinny Dubois (Anthony James). When the cowboys return with payment, Delilah, whose face now bears several scars, seems touched and nearly bound to forgiveness when the younger Davey offers his best pony not to Skinny but to his partner’s victim. Nevertheless, Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), the girls’ leader, wants blood. She pools together the girls’ savings to offer $1,000 to anyone who kills the two cowboys. For Little Bill, this means unsavory types, assassins, and gunslingers will arrive in his otherwise peaceful town.

As the film plays out, the plot itself acts to demystify Western legends. Consider the case of English Bob (Richard Harris), a hired gun for the railroads, and his biographer W. W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek), who follows Bob to write of his legend in a pulp magazine, colorfully titled “The Duke of Death”. A seemingly poised killer, Bob arrives in Big Whiskey with the intention of claiming the whores’ bounty, as his biographer listens to grandiose stories of the Wild West’s heyday in Bob’s convincing British droll. Indeed, Bob talks a good game and Beauchamp enthusiastically listens, believing and scribbling down every word, even adding his own “poetry” to the story on the printed page. But when English Bob is confronted by Little Bill, the confident gunslinger becomes a frail man under the bootheel of a superior force, who beats English Bob to set an example for any other would-be assassins in Big Whiskey looking to claim the bounty. Locked up for carrying a gun within the town’s limits, English Bob sits in his cell as Beauchamp listens to Little Bill paint a different picture of the Wild West, one where alleged hero English Bob survives only by the blundering of his opponents. By the time Little Bill kicks Bob—now dubbed “The Duck of Death”—out of town and threatens to kill him should he return, Beauchamp has resolved to stay in Big Whiskey and document Bill’s comparably authentic stories.

History was written by the winners, as they say, and English Bob was fortunate enough to win during his peak and haughty enough to brag and even lie about it later, knowing the press loves a good story. As the newspaperman in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance said, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” What Beauchamp learns is that inside every Wild West story resides the strength and weakness of men, and most often one is exaggerated and the other is downplayed. Little Bill has proven this by setting himself up as a bona fide gunslinger in his day and dismissing English Bob’s tall tales, talking to a once-again rapt Beauchamp about how drawing a gun relies less on speed than cool-headedness. And though Little Bill demonstrates himself to be a cruel and violent and capable man who defends Big Whiskey, Beauchamp overlooks Little Bill’s lesser qualities that suggest how he is putting on an act of a different sort—one of intimidation. Little Bill shows signs of weakness and incompetence that go ignored in Beauchamp’s absorption, such as his inability to construct his lakeside home with a single right angle. When it rains and the shoddy roof barely prevents any leaks, Beauchamp quips that Little Bill should shoot the carpenter, not realizing that Little Bill built the house himself. Rather than admit to his folly, Little Bill instead gives Beauchamp a prickly glare and moves on with his stories.

History was written by the winners, as they say, and English Bob was fortunate enough to win during his peak and haughty enough to brag and even lie about it later, knowing the press loves a good story. As the newspaperman in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance said, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” What Beauchamp learns is that inside every Wild West story resides the strength and weakness of men, and most often one is exaggerated and the other is downplayed. Little Bill has proven this by setting himself up as a bona fide gunslinger in his day and dismissing English Bob’s tall tales, talking to a once-again rapt Beauchamp about how drawing a gun relies less on speed than cool-headedness. And though Little Bill demonstrates himself to be a cruel and violent and capable man who defends Big Whiskey, Beauchamp overlooks Little Bill’s lesser qualities that suggest how he is putting on an act of a different sort—one of intimidation. Little Bill shows signs of weakness and incompetence that go ignored in Beauchamp’s absorption, such as his inability to construct his lakeside home with a single right angle. When it rains and the shoddy roof barely prevents any leaks, Beauchamp quips that Little Bill should shoot the carpenter, not realizing that Little Bill built the house himself. Rather than admit to his folly, Little Bill instead gives Beauchamp a prickly glare and moves on with his stories.

Back in Kansas, The Kid rides ahead but has convinced Munny to join in and split the bounty. Munny, rusty on a horse and even rustier with a firearm, rides along to enlist his former partner, Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), a gunslinger-turned-husband now living a quiet life. Ned agrees to go along and they meet up with The Kid, who boasts of his prowess as a killer in spite of his concerning poor eyesight. Heavy rains weaken the aged Munny, who, upon arriving armed in Big Whiskey, catches a fever and a fearful beating from the town’s enforcer, Little Bill, who rightly suspects Munny to be after the whores’ bounty. Munny escapes with Ned and The Kid and, over the next several days, together they track and kill the cowboys. But Ned finds he has lost his taste for violence over the years, and now, when confronted with killing again, finds himself incapable of pulling the trigger. Munny instead takes the shot that kills Davey Bunting, while Ned resolves to return home. The Kid, who admits to naming himself after his Schofield model Smith & Wesson revolver, barely lives up to his self-styled legend when he puts three bullets into a defenseless Quick Mike in an outhouse. Afterward, the killing, his now-confessed first, leaves The Kid scarred with shame until he finally realizes, “I ain’t like you, Will” as he guiltily swigs from a whiskey bottle. Even with Claudia’s lingering foothold over Munny, he was still able to kill. And with their bounty in hand, Munny’s relapse would seem to be only temporary, until with their payment comes the news that Little Bill has captured and killed Ned for Munny and The Kid’s crimes.

The strokes of Eastwood’s revisionist intentions can be seen as broad. Arguments that Unforgiven imparts the director’s personal commentary on Hollywood violence are poorly construed points of view, given the finale. And yet, Eastwood maintains that his intentions behind the film were to provide a commentary on violence in cinema, saying “We’ve reached a stage of our history, where I said to myself that violence shouldn’t be a source of humor or attraction.” Watching Eastwood’s film, however, his intentions do not reflect the outcome. Eastwood’s treatment of violence suggests the same degree of ambiguity that we feel toward Munny. The shootings, English Bob’s beating, and especially Ned’s whipping at the hands of Little Bill, have dire consequences; the violence itself is painful to behold, and the deaths are just as inglorious. Yet, violence also becomes a source of considerable gratification in the finale’s shootout. Eastwood does not deliver a Western based in pure entertainment value, since the catharsis felt by the finale cannot be ignored. The film’s revisionist moral implications lie not in the de-glorification of violence, but in the mystery of William Munny’s dear departed wife Claudia and her curious devotion to him noted in the opening, a mystery that lingers in the ending’s coda: “And there was nothing on the marker to explain to Mrs. Feathers why her only daughter had married a known thief and murderer, a man of notoriously vicious and intemperate disposition.”

The strokes of Eastwood’s revisionist intentions can be seen as broad. Arguments that Unforgiven imparts the director’s personal commentary on Hollywood violence are poorly construed points of view, given the finale. And yet, Eastwood maintains that his intentions behind the film were to provide a commentary on violence in cinema, saying “We’ve reached a stage of our history, where I said to myself that violence shouldn’t be a source of humor or attraction.” Watching Eastwood’s film, however, his intentions do not reflect the outcome. Eastwood’s treatment of violence suggests the same degree of ambiguity that we feel toward Munny. The shootings, English Bob’s beating, and especially Ned’s whipping at the hands of Little Bill, have dire consequences; the violence itself is painful to behold, and the deaths are just as inglorious. Yet, violence also becomes a source of considerable gratification in the finale’s shootout. Eastwood does not deliver a Western based in pure entertainment value, since the catharsis felt by the finale cannot be ignored. The film’s revisionist moral implications lie not in the de-glorification of violence, but in the mystery of William Munny’s dear departed wife Claudia and her curious devotion to him noted in the opening, a mystery that lingers in the ending’s coda: “And there was nothing on the marker to explain to Mrs. Feathers why her only daughter had married a known thief and murderer, a man of notoriously vicious and intemperate disposition.”

For reasons that remain unknown, this good woman Claudia forgave Munny for his trespasses because she saw something of worth in him. But since her death, Munny has not been able to forgive himself. Throughout the course of the film, he tries to convince himself that he has changed, that he no longer remains the cold-blooded killer he once was. In one scene on the trail, Munny asks Ned, “You remember that drover I shot through the mouth and his teeth came out the back of his head? I think about him now and again. He didn’t do anything to deserve to get shot, at least nothin’ I could remember when I sobered up.” Ned reminds Munny, “You ain’t like that no more.” Munny replies, “That’s right. I’m just a fella now. I ain’t no different than anyone else no more.” Except that his words sound uncertain, as if he speaks them to convince himself to verbalize it so that he will not fall into that trap again and betray Claudia’s memory. But then, seeking out this bounty betrays her memory and he knows it; he can feel himself becoming the Old William Munny again—that “killer of women and children”—and at least for a while, he resists it. That is, until the final scenes when, after Little Bill captures and kills Ned, and Skinny displays his body in public view, Munny takes the whiskey bottle from The Kid and falls back into drink. He will once again embrace the violent young man inside himself.

Munny orders The Kid to deliver Ned’s share of the bounty to Ned’s wife, and his own share to his children. The whiskey bottle is empty. Rain pours down but unlike before, it has no effect on Munny now; he will not become feverish and sickly. When he enters Skinny’s billiards hall where Ned’s body is displayed, he identifies the owner and shoots him dead. Little Bill steps forward, “Well, sir, you are a cowardly son of a bitch. You just shot an unarmed man!” Munny says flatly, “Well, he should have armed himself if he’s going to decorate his saloon with my friend.” Munny moves his shotgun barrel to take Little Bill down, but he misfires. In the ensuing ruckus, Munny shoots Little Bill’s deputies one-by-one with a pistol and no end of cool-headedness, and afterward, Beauchamp tries to interview him about what happened. Unlike English Bob and Little Bill, Munny has no need to venerate himself and tells Beauchamp to run off. Little Bill is still alive, barely, and Munny holds a barrel in front of his face. “I don’t deserve this…” Bill gurgles. “To die like this.” Munny, dismissive of any greater meaning to his actions, says “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it” and then pulls the trigger.

Munny orders The Kid to deliver Ned’s share of the bounty to Ned’s wife, and his own share to his children. The whiskey bottle is empty. Rain pours down but unlike before, it has no effect on Munny now; he will not become feverish and sickly. When he enters Skinny’s billiards hall where Ned’s body is displayed, he identifies the owner and shoots him dead. Little Bill steps forward, “Well, sir, you are a cowardly son of a bitch. You just shot an unarmed man!” Munny says flatly, “Well, he should have armed himself if he’s going to decorate his saloon with my friend.” Munny moves his shotgun barrel to take Little Bill down, but he misfires. In the ensuing ruckus, Munny shoots Little Bill’s deputies one-by-one with a pistol and no end of cool-headedness, and afterward, Beauchamp tries to interview him about what happened. Unlike English Bob and Little Bill, Munny has no need to venerate himself and tells Beauchamp to run off. Little Bill is still alive, barely, and Munny holds a barrel in front of his face. “I don’t deserve this…” Bill gurgles. “To die like this.” Munny, dismissive of any greater meaning to his actions, says “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it” and then pulls the trigger.

Everything about Unforgiven’s plot and much about its execution reflects a reverse image of classical Western tropes. The heroes defend the honor of prostitutes and not a God-fearing innocent. Rugged gunslingers are exposed as cowards and weaklings and liars, while others find they have outlived any desire to take another man’s life. Vain men try to make names for themselves, and their chronicler only further embellishes those names. The law is represented by a pitiless former gunslinger whose idea of order is fearful cruelty. Our self-reflecting protagonist resists his once violent ways only to become a cold-blooded killer again, suggesting that a Western hero is not necessarily “the good guy”, rather just the one who survived. Eastwood, as well as Peoples, become the authors of a true or “real” history, whereas we can be sure Beauchamp has no intention of writing an accurate account of what happens in the finale. He will print the Legend. Self-promoters like English Bob and Little Bill are the stuff of the Old West’s myths, but William Munny becomes the hard and unpleasant fact about the West—that heroes and villains were nowhere to be found. Legends did not exist. There were only men fuelled by drink and lawlessness, armed and riding free on the plains. Someone else embossed them into mythic status.

By 1992, the Western had diminished from a once-prosperous source of box-office splendor to an infrequently represented genre barely hanging on. The days of traditional Westerns where a white-clad champion defended justice from a black-clad desperado were, with a few exceptions, over in terms of their popularity. Of course, Revisionist Westerns had been around for decades, emerging with the films of Samuel Fuller (I Shot Jesse James (1949) and Forty Guns (1957)) and Anthony Mann (The Naked Spur (1953) and Man of the West (1958)), but now had changed into a resource for grand drama. Audiences wanted their Old West tales to ring of truth, yet humanity and Hollywood obliged with several epic Western revisions in the ‘90s. Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) won 7 Oscars and was favored among audiences for just its revisionist intentions, and in some way, Costner’s film seemed to make Eastwood’s possible. After earning just over $100 million in cinemas, Unforgiven would go on to earn 4 Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor for Gene Hackman, and Best Editing by Joel Cox. Moreover, Unforgiven paved the way for Tombstone (1993), Wyatt Earp (1994), The Quick and the Dead (1995), and Wild Bill (1995).

By 1992, the Western had diminished from a once-prosperous source of box-office splendor to an infrequently represented genre barely hanging on. The days of traditional Westerns where a white-clad champion defended justice from a black-clad desperado were, with a few exceptions, over in terms of their popularity. Of course, Revisionist Westerns had been around for decades, emerging with the films of Samuel Fuller (I Shot Jesse James (1949) and Forty Guns (1957)) and Anthony Mann (The Naked Spur (1953) and Man of the West (1958)), but now had changed into a resource for grand drama. Audiences wanted their Old West tales to ring of truth, yet humanity and Hollywood obliged with several epic Western revisions in the ‘90s. Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) won 7 Oscars and was favored among audiences for just its revisionist intentions, and in some way, Costner’s film seemed to make Eastwood’s possible. After earning just over $100 million in cinemas, Unforgiven would go on to earn 4 Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor for Gene Hackman, and Best Editing by Joel Cox. Moreover, Unforgiven paved the way for Tombstone (1993), Wyatt Earp (1994), The Quick and the Dead (1995), and Wild Bill (1995).

The film also marks a crucial turning point in Eastwood’s career, being the first of many self-reflective, persona-changing efforts to bear Eastwood’s mark in the coming years, whether his cinematic autobiography was an intentional subtext or not. From here on out, Eastwood expanded and matured as a filmmaker and screen presence; he redefined his image by acknowledging his age and expanding his breadth of storytelling. His usual Dirty Harry detective persona was rethought, and in a sense reinforced with Blood Work (2002); his hard-edged attitude received a makeover on Gran Torino (2008); he told the oft-one-sided WWII story from opposing perspectives in 2006 with his ambitious twin films Flag of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima. After Unforgiven, Eastwood’s films contained a pointed delicacy and sensitivity, a dramatic density of character and narrative seen in Mystic River (2003), Million Dollar Baby (2004), and Hereafter (2010), examples in which he did not have to star, though his presence is surely felt. Always thoughtful and crafted with confident hands, Eastwood’s films changed from action movies into deliberately paced, multi-faceted dramas of intricacy and emotion with complex characters like William Munny.

Eastwood’s masterful touch in Unforgiven lies in his capacity to span a measure of moral uncertainties and profound historical questioning, but with a sense of understanding for his characters. And strangely enough, his film remains accessible for a large filmgoing audience—whereas other films with such characteristics seem relegated exclusively to independent cinema. Only one other Western filmmaker ever balanced art and commerce so well in this genre, and that was John Ford. Artistic and commercial crowds flock more than ever to Eastwood’s output since Unforgiven, and he continues to challenge his mass of willing viewers with confronting questions and richly complicated characters. Here, violence and retribution never feel wholly justified, and yet the viewer cannot deny that Munny, killer though he may be, elicits our sympathy. By embracing the uncertainty behind Munny, the Old West, and American myths, Eastwood elevates a simple story by transcending the genre itself, and transforming his film into great art with the dynamic and compassion that has become his signature.

Eastwood’s masterful touch in Unforgiven lies in his capacity to span a measure of moral uncertainties and profound historical questioning, but with a sense of understanding for his characters. And strangely enough, his film remains accessible for a large filmgoing audience—whereas other films with such characteristics seem relegated exclusively to independent cinema. Only one other Western filmmaker ever balanced art and commerce so well in this genre, and that was John Ford. Artistic and commercial crowds flock more than ever to Eastwood’s output since Unforgiven, and he continues to challenge his mass of willing viewers with confronting questions and richly complicated characters. Here, violence and retribution never feel wholly justified, and yet the viewer cannot deny that Munny, killer though he may be, elicits our sympathy. By embracing the uncertainty behind Munny, the Old West, and American myths, Eastwood elevates a simple story by transcending the genre itself, and transforming his film into great art with the dynamic and compassion that has become his signature.

Bibliography:

Buscombe, Edward. Unforgiven (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, 2004.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review