The Definitives

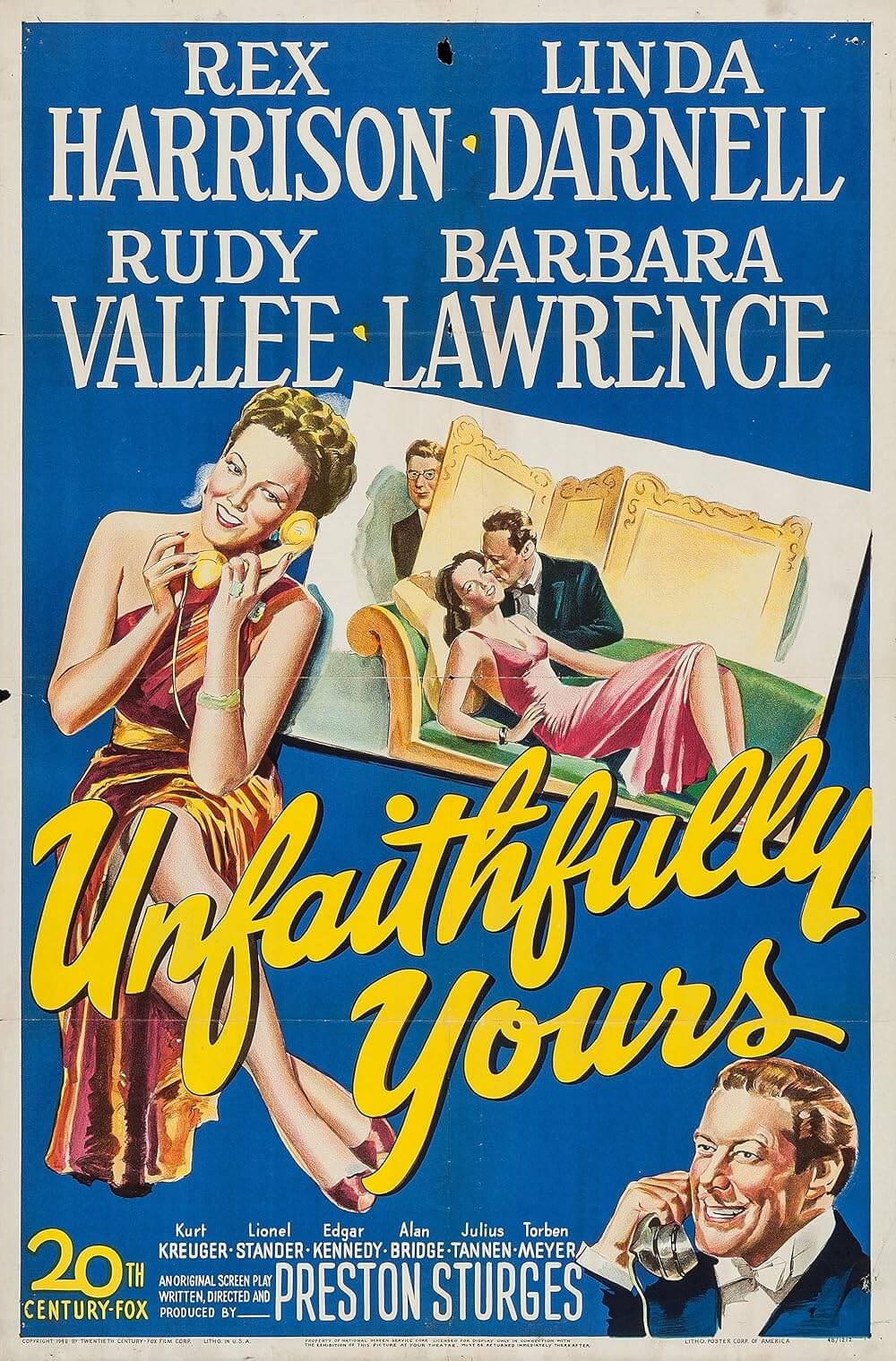

Unfaithfully Yours (1948)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In the last great film by Preston Sturges, the writer-director’s signature wit and slapstick come together with an hysterical sense of the macabre, forming a comedy far ahead of its time. And yet, Unfaithfully Yours has been described as a film in which nothing happens. The picture spends the better part of its runtime inside the obsessive imagination of its protagonist, an easily excitable concert conductor whose pathologically jealous state adds an uncommon vitality to his art. Played by Rex Harrison, the conductor’s mind becomes the stage on which the film’s fantasized events play out, ranging from elaborate traps to the slashing of a razor, from a humble goodbye to Russian roulette. Under the false impression that his faithful and loving wife is cheating on him, he directs his orchestra, and as he does so, he loses himself in the particular mood of the given composition. In a flurry of impassioned emotion shaped by selections from Gioacchino Rossini, Richard Wagner, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, he visualizes himself in a series of sometimes vengeful fantasies. Sturges explores the notion that music not only shapes our mood but that our perceptions of the world are rarely accurate. Sturges’ dark comedy plays in the mind of a paranoiac genius not unlike himself, producing a film that represents his last great effort after a series of earlier hits. Though both the public and the studio failed to understand Unfaithfully Yours upon its release in 1948, it has since been rediscovered by more sophisticated audiences and included on the long list of Sturges masterpieces.

Unfaithfully Yours is also a perfect example of how Sturges often took a theory or observation about people and developed it into a feature. During its release, the critic for The Hollywood Reporter reduced Unfaithfully Yours to its most basic components, calling it “a fanciful film dealing with an idea instead of a plot”. But Sturges could make investigations of a singular idea into a riotous comedy, such as how The Palm Beach Story (1942) explored his belief that a pretty woman need never pay for anything. In the pages of The New York Times, Manny Farber once described Sturges as “a satirist without any stable point of view from which to aim his satire.” On the contrary, this film’s point of view was familiar for the writer-director—that of a jealous artist—while his target remains incredibly unique because Sturges aimed his satire inward at our most personal darkest thoughts. But by 1948, the potential humor in murder had not yet reached the mainstream. Alfred Hitchcock’s widely held brand of comic-macabre signatures in films like The Trouble with Harry (1955) or his television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1961) had not yet been popularized, and Unfaithfully Yours would have much in common with works by the Master of Suspense. Moreover, just a year before Sturges’ film reached theaters, Charles Chaplin released Monsieur Verdoux (1947), a comedy about a man who marries rich women and murders them for their money. Just like Unfaithfully Yours, Chaplin’s picture was rejected upon its debut and later reappraised by critics and audiences. Chaplin and Sturges had peaked into the dark unconscious that viewers wanted to explore with levity, even if no one wanted to admit it at the time.

Harrison plays world-famous conductor Sir Alfred de Carter, who arrives home from England with a warm greeting from his much younger, beautiful wife, Daphne (Linda Darnell). But his brother-in-law August (Rudy Vallee) has troubling news. August misunderstood Sir Alfred’s orders to look after his wife, and in turn hired a private investigator to watch Daphne while Sir Alfred was away. Sir Alfred, prejudiced again private detectives, is outraged at the thought of flatfoots following his beloved wife. But he soon learns that Daphne made a late-night trip to the hotel room of Sir Alfred’s assistant, Tony (Kurt Kreuger), a good-looking man of her own age. Now convinced Daphne and Tony are having an affair, Sir Alfred takes the stage to conduct his first of three selections, the lively overture to Rossini’s Semiramide, and while waving his wand he imagines killing Daphne and framing Tony for the murder. He conceives himself recording and manipulating his voice to sound like a woman screaming for help; then he proposes that Daphne should call Tony to take her dancing, if only to draw Tony into their room. His fantasy continues when Sir Alfred imagines slashing Daphne to death with his razor, and once Tony arrives to pick Daphne up, the conductor has arranged it so Tony is arrested once the screaming woman recording alerts authorities. As Tony is sentenced to execution for murder, Sir Alfred imagines himself laughing like a madman in the courtroom. Sir Alfred’s next daydream comes after a break in the concert, when he conducts a somber selection from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, to which he sees himself humble and forgiving—in his musing, he even writes Daphne a check and admits quite selflessly, “Youth belongs to youth.” For his last performance, Sir Alfred conducts Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini; at the same time, he sees himself forcing Daphne and Tony into a game of Russian roulette, the first shot of which tragically enters Sir Alfred’s head.

Harrison plays world-famous conductor Sir Alfred de Carter, who arrives home from England with a warm greeting from his much younger, beautiful wife, Daphne (Linda Darnell). But his brother-in-law August (Rudy Vallee) has troubling news. August misunderstood Sir Alfred’s orders to look after his wife, and in turn hired a private investigator to watch Daphne while Sir Alfred was away. Sir Alfred, prejudiced again private detectives, is outraged at the thought of flatfoots following his beloved wife. But he soon learns that Daphne made a late-night trip to the hotel room of Sir Alfred’s assistant, Tony (Kurt Kreuger), a good-looking man of her own age. Now convinced Daphne and Tony are having an affair, Sir Alfred takes the stage to conduct his first of three selections, the lively overture to Rossini’s Semiramide, and while waving his wand he imagines killing Daphne and framing Tony for the murder. He conceives himself recording and manipulating his voice to sound like a woman screaming for help; then he proposes that Daphne should call Tony to take her dancing, if only to draw Tony into their room. His fantasy continues when Sir Alfred imagines slashing Daphne to death with his razor, and once Tony arrives to pick Daphne up, the conductor has arranged it so Tony is arrested once the screaming woman recording alerts authorities. As Tony is sentenced to execution for murder, Sir Alfred imagines himself laughing like a madman in the courtroom. Sir Alfred’s next daydream comes after a break in the concert, when he conducts a somber selection from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, to which he sees himself humble and forgiving—in his musing, he even writes Daphne a check and admits quite selflessly, “Youth belongs to youth.” For his last performance, Sir Alfred conducts Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini; at the same time, he sees himself forcing Daphne and Tony into a game of Russian roulette, the first shot of which tragically enters Sir Alfred’s head.

Once he completes his concert, Sir Alfred rushes home to prepare Daphne and Tony’s demise, but without the music to guide him, he bungles through each of his three ill-conceived plots. He tries to find his vinyl “home recording unit” to record the screaming voice that will alert authorities, but in the process, he nearly trashes his entire room looking for it—crashing over furniture, breaking lamps, and stepping on light bulbs. He’s hardly the suave killer he imagined himself to be. Once he finds the cumbersome box tucked away in a closet, he struggles to understand its instructions, which frustratingly read “So Simple It Operates Itself”. Before he can finish, Daphne arrives home, baffled at her husband’s unruly and unexplained behavior throughout the evening. Sir Alfred tries to convince Daphne to go dancing with Tony, but she’s not interested; Tony is a terrible dancer, she explains. After all, there is no affair; Sir Alfred followed “circumstantial” evidence and his own insecurities to the worst possible conclusion. His love for her is so strong, while his own ego is so fragile, that the mere thought of betrayal has sent him spiraling out of control. As he tries to carry out his second fantasy—where he behaves nobly and writes her a check—he instead remains irritable, petty, and graceless, spilling ink all over his checkbook. Finally, he cannot find bullets for his gun, which means he will not be playing Russian roulette either. At last, Daphne explains beyond any doubt the misunderstanding in the private eye’s report, and she writes off Alfred’s base assumptions as a natural part of an artist’s great, consumed mind. Sir Alfred puts aside his suspicions and insecurities about his age, and he announces that tonight the two of them will dress vulgar, drink magnums of champagne, and go dancing.

Sturges first conceived the idea in 1932 while writing at Universal Studios. He had a scene for The Power and the Glory entirely sketched out in his head; but when he typed it out, the scene played much differently than he imagined it. “I sat back wondering what the hell had happened, then realized that someone had left the radio on in the next room and realized that I had been listening to a symphony broadcast from New York and that this, added to my thoughts, had changed the total.” Sturges developed this concept into a script, originally called “The Concert”, with the intent to explore how music can unintentionally shape someone’s feelings and perceptions. His screenplay centered on a conductor whose concert influences his mindset while he conducts. The character’s internal thoughts would represent nearly the entire body of the picture. As Sturges wrote, the specific content of the conductor’s thoughts developed over time into darkly funny and ghastly sequences that reflected Sturges’ own preoccupations, jealousy, and obsessions—feelings he attributed to a sometimes common self-absorption experienced by particularly expressive artists. He pitched his idea to Paramount Pictures and Twentieth Century Fox under the title “Unfinished Symphony”, but the studios balked at what they believed was an unmarketable idea. Part of the problem was the pitch itself, specifically the title. “Improper Relations”, “Lover-in-Law”, and “The Symphony Story” were all other options. Fox’s head Darryl F. Zanuck finally picked up Sturges’ script in 1947 under the condition that the word “symphony” not appear in the title.

Sturges first conceived the idea in 1932 while writing at Universal Studios. He had a scene for The Power and the Glory entirely sketched out in his head; but when he typed it out, the scene played much differently than he imagined it. “I sat back wondering what the hell had happened, then realized that someone had left the radio on in the next room and realized that I had been listening to a symphony broadcast from New York and that this, added to my thoughts, had changed the total.” Sturges developed this concept into a script, originally called “The Concert”, with the intent to explore how music can unintentionally shape someone’s feelings and perceptions. His screenplay centered on a conductor whose concert influences his mindset while he conducts. The character’s internal thoughts would represent nearly the entire body of the picture. As Sturges wrote, the specific content of the conductor’s thoughts developed over time into darkly funny and ghastly sequences that reflected Sturges’ own preoccupations, jealousy, and obsessions—feelings he attributed to a sometimes common self-absorption experienced by particularly expressive artists. He pitched his idea to Paramount Pictures and Twentieth Century Fox under the title “Unfinished Symphony”, but the studios balked at what they believed was an unmarketable idea. Part of the problem was the pitch itself, specifically the title. “Improper Relations”, “Lover-in-Law”, and “The Symphony Story” were all other options. Fox’s head Darryl F. Zanuck finally picked up Sturges’ script in 1947 under the condition that the word “symphony” not appear in the title.

By the time Sturges finally settled on Unfaithfully Yours as the title of his unproduced “bedroom farce” from 1932, his career had taken a shocking downturn. Between 1940 and 1944, Sturges had experienced an incomparable string of box-office hits, beginning with The Great McGinty and Christmas in July in 1940, The Lady Eve and Sullivan’s Travels in 1941, The Palm Beach Story in 1942, and both The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek and Hail the Conquering Hero in 1944. In a span of only four years, Sturges proved himself incredibly prolific and renowned throughout Hollywood for his intelligent screwball comedies. Because of this, the studios allotted him an uncommon artistic freedom, which Sturges tested with films like The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, a risqué comedy about an unmarried pregnant woman unsure of who fathered her baby. Sturges’ confidence in his output and faith in his audience was tested in 1944, when he released the largely dramatic The Great Moment, about the nineteenth-century dentist who discovered that ether could be used for general anesthesia. After The Great Moment bombed, which Sturges attributed to studio meddling, the writer-director left his home studio of Paramount and, as many of top Hollywood talents had done in the 1940s, formed an independent studio. He called it California Pictures and, alongside the new studio’s co-founder Howard Hughes, Sturges began production on The Sin of Harold Diddlebock with Harold Lloyd starring. The troubled production resulted in feuds between its star and director, as well as a falling out between Hughes and Sturges. As the director went incredibly over budget and received indifferent reviews at early screenings, Hughes took over the production, re-edited the film, shot new scenes, and released it under the title Mad Wednesday.

By 1947, the same year as separate releases for The Sin of Harold Diddlebock and Mad Wednesday, Sturges needed another payday and another box-office hit to sustain what had become an extravagant Hollywood lifestyle. In that respect, he went to Fox somewhat desperate, needing the director’s job as he had not needed one before. Nevertheless, Zanuck signed Sturges to a two-picture deal, because Sturges’ track record was still largely impressive at the time. For the first film in the Fox deal, Sturges wanted to make a Betty Grable musical-Western (eventually called The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend, from 1949), but his script was not yet ready. That’s when Sturges dusted off his trunk script for Unfaithfully Yours, and it became the first film produced under his deal with Fox. And despite the director’s recent failures behind the camera, Zanuck allowed him the artistic freedoms he had grown accustomed to. Sturges even rewrote the part of Daphne for his lover, Frances Ramsden, whose back problems had delayed the start of production. For his male lead, Sturges wanted James Mason to star, but Mason was unavailable. Contracted Fox actor Rex Harrison was his second choice. When filming could not begin because of Ramsden, Zanuck insisted that Sturges recast the role, and ultimately the producer chose Gene Tierney, who already starred oppose Harrison in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), and as a result provided a more bankable presence onscreen than the unknown and inexperienced Ramsden. Tierney backed out as well, and the role finally went to Darnell. To prepare Harrison to play Sir Alfred, actor and conductor Robert Sanders-Clark labored to teach the actor how to become a conductor. Harrison and Sanders-Clark worked until all hours of the night until Harrison could count beats, follow the music, and plan his conductor movements along with his counting. The result would prove convincing enough to fool critics and audiences at the time, but his delivery also convinced the on-set orchestra, which followed Harrison’s baton during their performance.

By 1947, the same year as separate releases for The Sin of Harold Diddlebock and Mad Wednesday, Sturges needed another payday and another box-office hit to sustain what had become an extravagant Hollywood lifestyle. In that respect, he went to Fox somewhat desperate, needing the director’s job as he had not needed one before. Nevertheless, Zanuck signed Sturges to a two-picture deal, because Sturges’ track record was still largely impressive at the time. For the first film in the Fox deal, Sturges wanted to make a Betty Grable musical-Western (eventually called The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend, from 1949), but his script was not yet ready. That’s when Sturges dusted off his trunk script for Unfaithfully Yours, and it became the first film produced under his deal with Fox. And despite the director’s recent failures behind the camera, Zanuck allowed him the artistic freedoms he had grown accustomed to. Sturges even rewrote the part of Daphne for his lover, Frances Ramsden, whose back problems had delayed the start of production. For his male lead, Sturges wanted James Mason to star, but Mason was unavailable. Contracted Fox actor Rex Harrison was his second choice. When filming could not begin because of Ramsden, Zanuck insisted that Sturges recast the role, and ultimately the producer chose Gene Tierney, who already starred oppose Harrison in The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), and as a result provided a more bankable presence onscreen than the unknown and inexperienced Ramsden. Tierney backed out as well, and the role finally went to Darnell. To prepare Harrison to play Sir Alfred, actor and conductor Robert Sanders-Clark labored to teach the actor how to become a conductor. Harrison and Sanders-Clark worked until all hours of the night until Harrison could count beats, follow the music, and plan his conductor movements along with his counting. The result would prove convincing enough to fool critics and audiences at the time, but his delivery also convinced the on-set orchestra, which followed Harrison’s baton during their performance.

Filming began on February 18, 1948, with a budget of just under $2 million and a 60-day shooting schedule. The price tag was nearly three times as much as what it cost Sturges to shoot The Lady Eve and more than double Sullivan’s Travels. The press began to question the director about his ballooning budgets in the struggling postwar economy, to which Sturges replied, “Anybody can make money in good times, even with lousy pictures. Now is the time to put good money into good pictures.” Sturges completed filming on time and under his budget. Zanuck’s initial reaction to the press was that Unfaithfully Yours was a “wonderful, wonderful comedy”. Privately, Zanuck believed the final product to be overlong and overpriced. He complained that Sturges was allowed far too much time to edit the picture; after all, due to Sturges’ reputation, the writer-director’s allotted time in the editing room was three-times longer than other directors at Fox. And perhaps Sturges would have had his original 126-minute cut if some ninety members of the initial preview audience had not walked out during the show. The film received the worst possible reception any film can receive from a preview screening: audiences were polarized between love and hate. In response, Zanuck demanded that Sturges reduce the film’s length to no more than 105 minutes, which is exactly where the film clocks. The finished film was ready for a July 4, 1948, release, but then tragedy struck and delayed the debut. Harrison’s mistress at the time, Carol Landis, died from an overdose of Seconal. The press hounded the bereaved actor with questions on the scandal, though he refused to make any statements, as did the Fox publicity team on his behalf. “The studio could have given me some support,” he wrote years later in his autobiography. Meanwhile, Harrison had two films ready for release, Unfaithfully Yours and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Escape, but Fox delayed both over Harrison’s loss.

When Unfaithfully Yours eventually opened on November 6 of 1948, it was booked in the Roxy Theater in New York City, a massive venue with 6,200 seats. The film’s receipts were some of the worst reported in Roxy’s history. Among otherwise favorable reviews, some condemned the film, including the aforementioned appraisal in The Hollywood Reporter, which described it as “slight, repetitious, and forced”. Zanuck predicted, “We are certainly in for one of the biggest beatings in history.” When Fox expanded its distribution to an additional five theaters in Los Angeles, along with an alternative ad campaign that marketed the film as a thriller, their ploy ultimately failed. Fox quickly pulled prints from distribution and Sturges’ film was buried for years. Sturges’ reputation had reached an unrecoverable low. He scrambled to get back on top again, but his next film, The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend, fared even worse. The director never achieved another hit. His last film, The French, They Are a Funny Race (1955), was received with even greater disdain than his worst-reviewed directorial effort, The Great Moment. Besides his string of flops, Sturges’ egocentric and temperamental behavior, his insistence on creative autonomy, and his habit of testing the studios’ limits with his suggestive, often provocative material, resulted in several behind-the-scenes battles with the studios. When he was profitable, the studios tolerated his behavior and happily fought such battles; now that his films failed to turn a profit, they wanted nothing to do with him. He wrote in his autobiography, “In twenty-two years, I managed to alienate every one of the seven major studios and soon found myself out of work.” Hollywood had rarely seen anything so radical as the rise and fall of director Preston Sturges from 1932 to 1955. Though he was once the highest paid person in the entire industry, Sturges was virtually unemployable in the end. He died of a heart attack in 1959.

When Unfaithfully Yours eventually opened on November 6 of 1948, it was booked in the Roxy Theater in New York City, a massive venue with 6,200 seats. The film’s receipts were some of the worst reported in Roxy’s history. Among otherwise favorable reviews, some condemned the film, including the aforementioned appraisal in The Hollywood Reporter, which described it as “slight, repetitious, and forced”. Zanuck predicted, “We are certainly in for one of the biggest beatings in history.” When Fox expanded its distribution to an additional five theaters in Los Angeles, along with an alternative ad campaign that marketed the film as a thriller, their ploy ultimately failed. Fox quickly pulled prints from distribution and Sturges’ film was buried for years. Sturges’ reputation had reached an unrecoverable low. He scrambled to get back on top again, but his next film, The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend, fared even worse. The director never achieved another hit. His last film, The French, They Are a Funny Race (1955), was received with even greater disdain than his worst-reviewed directorial effort, The Great Moment. Besides his string of flops, Sturges’ egocentric and temperamental behavior, his insistence on creative autonomy, and his habit of testing the studios’ limits with his suggestive, often provocative material, resulted in several behind-the-scenes battles with the studios. When he was profitable, the studios tolerated his behavior and happily fought such battles; now that his films failed to turn a profit, they wanted nothing to do with him. He wrote in his autobiography, “In twenty-two years, I managed to alienate every one of the seven major studios and soon found myself out of work.” Hollywood had rarely seen anything so radical as the rise and fall of director Preston Sturges from 1932 to 1955. Though he was once the highest paid person in the entire industry, Sturges was virtually unemployable in the end. He died of a heart attack in 1959.

Unfaithfully Yours exemplifies how rare a talent Sturges was—an artist whose egoism had been justified by his proven intelligence and early directorial successes. But without such validations, his behavior would have been intolerable. Fortunately, the director was aware of his own downfalls, enough to incorporate his behavior into Sir Alfred. Indeed, Harrison was playing a role Sturges based on himself, complete with mood swings, bouts of foul temper, and even the director’s unique penchant for orating what would otherwise be inner monologues. And what could be more like a film director than an orchestra conductor—someone who waves his wand to cast a spell on other artists to perform his commands? As a result, Sturges personalized Unfaithfully Yours more than his other films. His lover at the time, Frances Ramsden, was twenty-four years younger than the director, who was then almost fifty. His insecurities over their winter-summer romance inspired several references to divergent age relations within the film; Ramsden herself later attested that Unfaithfully Yours had more than a few autobiographical flourishes. Casting Ramsden in the role of Daphne as Sturges originally intended would have lent the picture an art-imitates-life edge that preceded even Hitchcock’s own obsessive direction of his blonde actresses, notably Tippi Hedren, with whom Hitchcock was infatuated. Meanwhile, by basing the character on himself and making Sir Alfred a conductor, Sturges embraced his intellectual side more than his earlier work. He made use of his love for classical music and selected each piece of music carefully to reflect Sir Alfred at the time of its use. In both its internal autobiographism and the Freudian manner in which it explores dreams, Unfaithfully Yours has much in common with Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963).

Unique for his time and genre, Sturges explores a wonderfully Kafkaesque character who can clearly see what he wants to accomplish in his mind’s eye, and yet, humorously and quite exasperatingly, he cannot carry out the actions as he has seen them. It’s almost as though the universe operates against Sir Alfred, except that his perception of the universe has been characterized by his own fragile subjectivity. With each episode imagined in Sir Alfred’s mind, cinematographer Victor Milner’s camera peers into the character’s pupil after a long, impressive zoom across the orchestra. Few images could be more Freudian than the human eye, a visual cue employed by Hitchcock on a number of films from Spellbound to Psycho. Inside, the character’s every impulse—every murderous, exposed, angry, and jealous whim—seems possible and has been considered by the subject. Another moment, a shocking image where Sir Alfred shoots himself in the head, overlays the bullet hole with a swirling whirlpool, anticipating the famous shower drain and eye juxtaposition in Psycho. Sturges’ specific use of this optical effect better anticipates the way Hitchcock’s frame entered into eyes in Vertigo, another film that explores the sexual obsessions of its protagonist. From inside Sir Alfred’s mind, his fantasies and nightmares come pouring out upon the screen, unadulterated and unreserved. His behavior is terrible and petty, from downright violent to utterly maniacal, and the viewer almost feels embarrassed by how shameful his behavior becomes within the course of his daydreams, as if we have entered a particularly private session of psychoanalysis and overheard secrets no one else will ever hear. After all, the character’s feelings are never really expressed in a direct way; Sir Alfred never confesses his murderous feelings to Daphne.

Unique for his time and genre, Sturges explores a wonderfully Kafkaesque character who can clearly see what he wants to accomplish in his mind’s eye, and yet, humorously and quite exasperatingly, he cannot carry out the actions as he has seen them. It’s almost as though the universe operates against Sir Alfred, except that his perception of the universe has been characterized by his own fragile subjectivity. With each episode imagined in Sir Alfred’s mind, cinematographer Victor Milner’s camera peers into the character’s pupil after a long, impressive zoom across the orchestra. Few images could be more Freudian than the human eye, a visual cue employed by Hitchcock on a number of films from Spellbound to Psycho. Inside, the character’s every impulse—every murderous, exposed, angry, and jealous whim—seems possible and has been considered by the subject. Another moment, a shocking image where Sir Alfred shoots himself in the head, overlays the bullet hole with a swirling whirlpool, anticipating the famous shower drain and eye juxtaposition in Psycho. Sturges’ specific use of this optical effect better anticipates the way Hitchcock’s frame entered into eyes in Vertigo, another film that explores the sexual obsessions of its protagonist. From inside Sir Alfred’s mind, his fantasies and nightmares come pouring out upon the screen, unadulterated and unreserved. His behavior is terrible and petty, from downright violent to utterly maniacal, and the viewer almost feels embarrassed by how shameful his behavior becomes within the course of his daydreams, as if we have entered a particularly private session of psychoanalysis and overheard secrets no one else will ever hear. After all, the character’s feelings are never really expressed in a direct way; Sir Alfred never confesses his murderous feelings to Daphne.

Because Sir Alfred never carries out Daphne’s murder, and Daphne never learns how close she came to oblivion, Unfaithfully Yours bears a certain resemblance to Hitchcock’s Suspicion. In the 1940 release, Joan Fontaine stars as a wife whose new husband, played by the charming Cary Grant, seems to be plotting the murder of his pet-named wife “monkeyface” to resolve his gambling debts. Through the course of the film, she has a few close calls, but the suspense is ultimately all in her head (and ours), since her husband never had any plans to murder her. (NOTE: In Hitchcock’s original treatment, Grant’s character was trying to kill his wife; however, the studio decided that the audiences would not want to see the exceedingly popular and charming Grant play such an against-type role.) Hitchcock manipulated the orchestral score and camerawork to influence the audience’s reactions, delivering what is largely an empty, meaningless experience. The subject of both Hitchcock and Sturges’ film is deceptive, in that they plant the expectation of murder, whereas no murder will ever take place. Instead, they consider the everyday state of mind common in many human beings and our relationships, where we offer our trust to another person but the completeness of that trust, and the degree to which we can truly know someone, remains finite. A level of secrecy exists in every relationship, no matter how open it may seem. Sturges and Hitchcock’s film suggest that behind every set of eyes lurks a mind that, whether it intends to carry out such thoughts or not, thinks of murder.

After Sir Alfred completes the first performance of his concert, his manager asks what inspired it: “What did you have in your head?” Sir Alfred conjures a sinister smile and replies, “You’d be enormously surprised if you knew.” Watching Unfaithfully Yours, the viewer imagines that Sir Alfred finds some reason, any reason, to go through this series of morbid, jealous, and self-indulgent outbursts during each of his concerts, and that this episode represents just one of many such incidents in a pattern of volatile behavior. Consequently, the viewer also imagines that Sturges went through something similar when he ruminated about the concepts that drove his films, specifically those about the relationships between men and women. Though hints of Sturges’ autobiographical influence and openness to macabre comedy give Unfaithfully Yours its distinctive pitch, and it certainly represents an advanced perspective for 1948, his film remains a testament to the sometimes tortured state of great artists, from Van Gogh to Jim Morrison, and the frantic process of creation they require. For Sturges, creating great art meant that an artist must engage in an emotional process, no matter how intelligent the artist may be. Despite being a genius, Sturges never wanted that label, nor did he want to thrust his intellect upon his audience in any way that would compromise the pure entertainment value of his cinema—so much so that he sought to underscore the outlandishness of such behavior by making a film about it. With Unfaithfully Yours, he tests his own boundaries and that of his entertainment, and he hides his rare wit behind a comedy of dark emotions.

After Sir Alfred completes the first performance of his concert, his manager asks what inspired it: “What did you have in your head?” Sir Alfred conjures a sinister smile and replies, “You’d be enormously surprised if you knew.” Watching Unfaithfully Yours, the viewer imagines that Sir Alfred finds some reason, any reason, to go through this series of morbid, jealous, and self-indulgent outbursts during each of his concerts, and that this episode represents just one of many such incidents in a pattern of volatile behavior. Consequently, the viewer also imagines that Sturges went through something similar when he ruminated about the concepts that drove his films, specifically those about the relationships between men and women. Though hints of Sturges’ autobiographical influence and openness to macabre comedy give Unfaithfully Yours its distinctive pitch, and it certainly represents an advanced perspective for 1948, his film remains a testament to the sometimes tortured state of great artists, from Van Gogh to Jim Morrison, and the frantic process of creation they require. For Sturges, creating great art meant that an artist must engage in an emotional process, no matter how intelligent the artist may be. Despite being a genius, Sturges never wanted that label, nor did he want to thrust his intellect upon his audience in any way that would compromise the pure entertainment value of his cinema—so much so that he sought to underscore the outlandishness of such behavior by making a film about it. With Unfaithfully Yours, he tests his own boundaries and that of his entertainment, and he hides his rare wit behind a comedy of dark emotions.

Bibliography:

Curtis, James. Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, c1982.

Harvey, James. Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, from Lubitsch to Sturges. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Sturges, Preston; Sturges, Tom. Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review