The Definitives

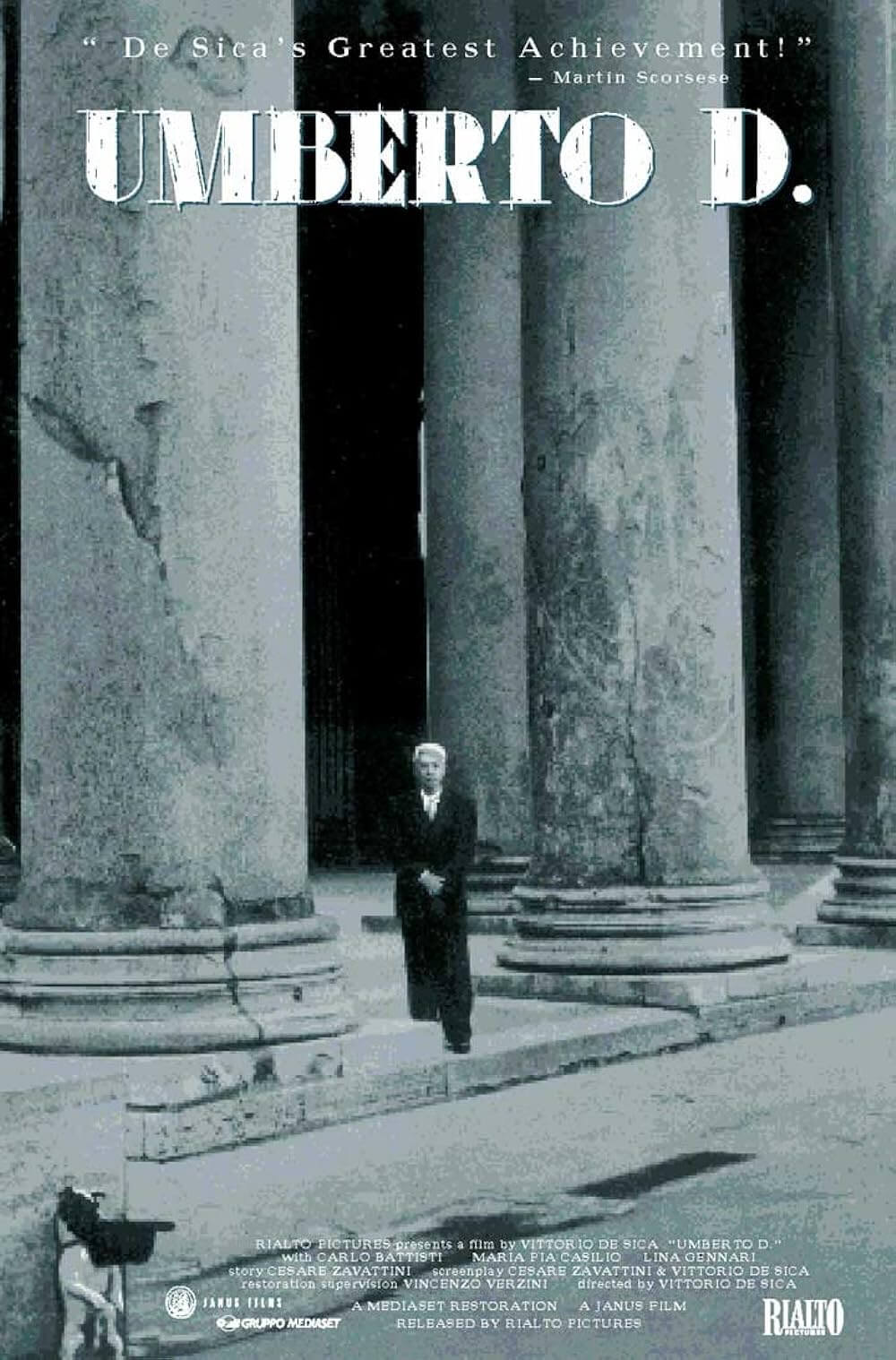

Umberto D.

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. envelops us in a seemingly futile search for dignity, within a hopeless, unsympathetic world almost incapable of recompense and riddled by indifference toward the individual. Presenting a sentimental version of Italian neorealism, the cinematic movement in which De Sica made his name, the director embraces the common man through everyday struggles, but also through the heart’s journey to find some reason to endure. Even while structuring his narrative around the emotional validation of one man by way of his best friend, a dog, the drama never feels artificial or maudlin, as common as such a story may be. Opening on a demonstration held by a crowd of aged pensioners, the film begins with citizens shouting for “justice” and higher annuities. Police break up the rabble in jeeps, honking at the men and chasing them from the square in Rome like a flock of pesky geese. De Sica sets his stage with various shots of protesters, among them the anonymous face of Umberto Domenico Ferrari (Carlo Battisti), shown briefly here and there. Without a permit to rally, the pensioners are waved away, though most can survive on their allowance anyway. Umberto cannot, probably for the first time in his life. Throughout the film, he speaks to acquaintances and former co-workers about his debts, dancing around asking them for help out of pride. When he attempts to hawk his watch, they see right through his act and quickly escape the conversation.

Given that Umberto’s problem is clearly his own, De Sica is not constructing a social commentary about the lacking stipend for retirees provided by the government. Instead, De Sica challenges our sympathy for an anonymous individual, a face in the crowd. Italian neorealists drew their power from the populace by returning the spotlight to everyday people, by accepting reality, and acknowledging the drama in daily toils. Early examples of the movement, including Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) and De Sica’s own Shoeshine (1946), resisted the Fascist idealisms that left Italy broken after World War II, and in its place depicted, as Cesare Zavattini, the screenwriter of Umberto D. put it, “life as it is.” The choice of realism separated the filmmakers from the sheer self-deluding fantasy of the Fascists. And French poetic neorealists such as Jean Renoir and René Clair influenced De Sica, Rossellini, Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini, and other neorealist filmmakers, as their “real” cinema offered the truth—sans heightened emotionalism—these Italians aspired to.

Desperate to survive with some semblance of dignity, Umberto’s life winds down. He is without employment, family, his health, or anything else to cling to. While away, his landlady (Lina Gennari) rents out his ant-ridden room by the hour to adulterous couples, and when he complains, she gripes at him about the back rent. The maid in his rooming house, Maria (Maria-Pia Casilio), is pregnant, but she cannot be sure if the father is her inamorato from Florence or from Naples. Umberto does not blame her; he scolds the young men for not seeing to their duty. He understands that Maria too has found herself trapped, and since they share a mutual prison, they are friends. De Sica describes these characters as ordinary people, shooting on actual locations to capture their world like an observer on the scene. Consciously long examinations on the every day, such as an extended rumination on Maria’s morning routine, signify the authenticity of these people. Outdoors, among the ancient architecture of Rome, De Sica finds a surplus of visual wealth to activate his picture, including lively walkways, visually arresting squares and street arrangements. Attention is focused on meek, everyday locations, versus bold iconography representing the former glory of ancient Romans—no Colosseum, Pantheon, or vertical pan up Trajan’s Column. His most dynamic pieces of sculpture are the cracks in Umberto’s face.

Desperate to survive with some semblance of dignity, Umberto’s life winds down. He is without employment, family, his health, or anything else to cling to. While away, his landlady (Lina Gennari) rents out his ant-ridden room by the hour to adulterous couples, and when he complains, she gripes at him about the back rent. The maid in his rooming house, Maria (Maria-Pia Casilio), is pregnant, but she cannot be sure if the father is her inamorato from Florence or from Naples. Umberto does not blame her; he scolds the young men for not seeing to their duty. He understands that Maria too has found herself trapped, and since they share a mutual prison, they are friends. De Sica describes these characters as ordinary people, shooting on actual locations to capture their world like an observer on the scene. Consciously long examinations on the every day, such as an extended rumination on Maria’s morning routine, signify the authenticity of these people. Outdoors, among the ancient architecture of Rome, De Sica finds a surplus of visual wealth to activate his picture, including lively walkways, visually arresting squares and street arrangements. Attention is focused on meek, everyday locations, versus bold iconography representing the former glory of ancient Romans—no Colosseum, Pantheon, or vertical pan up Trajan’s Column. His most dynamic pieces of sculpture are the cracks in Umberto’s face.

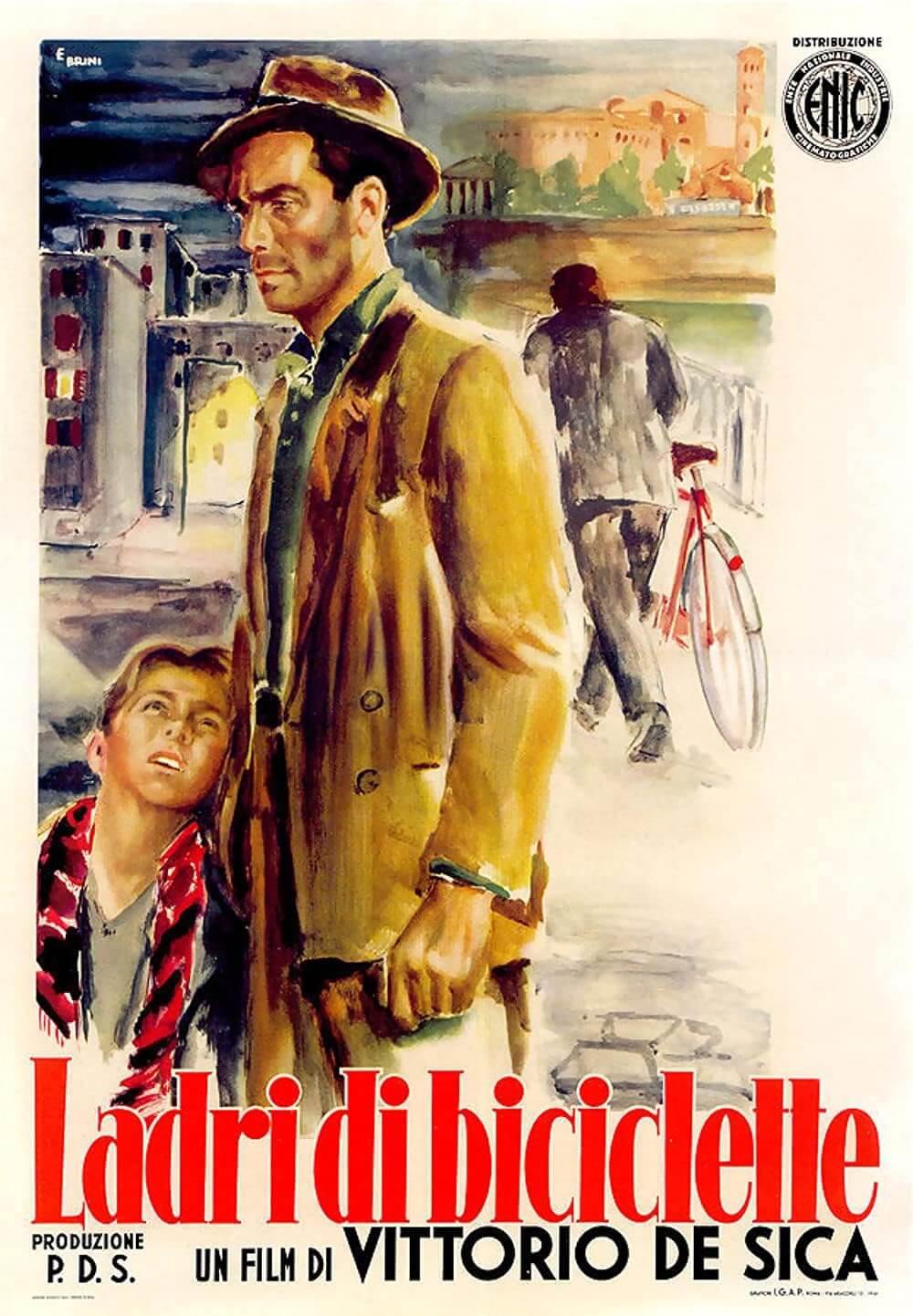

Neorealism initially sought to contribute to society by empowering the disempowered. Filmic heroes of the movement were flawed everyday types with no prospects and even less money in their pockets. De Sica defined this archetype years before Umberto D. in 1948 with Bicycle Thieves, wherein a man so desperate to keep his job steals transportation and remains sympathetic for it. Its subjects and the method in which they were depicted define neorealism; however, compositionally, the movement’s films were manufactured to be real and thus were effectively manipulative in their verisimilitude. French critic André Bazin, who adored De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, called the film “pure cinema.” The question then arises: How do you make a “true” film without obvious great effort placed onto the production? Shot on the ground level and whenever possible on location, neorealist films and filmmakers avoid sweeping shots, bravado camerawork, the use of studio sets, and the visual notation of aggrandizing imagery. Stories unfold naturally, the characters often literally emerging from the crowds, as with Umberto. Even while hoping to reinvent cinema in the name of Italian nationalism, the movement employs classically dramatic methods to portray events and characters that are ardently real. Carlo Battisti was 70-years-old when he made Umberto D. He had never acted, nor would he ever act again. Untrained actors provided neorealists with an unformed block they could mold. Such performers arrive on set projecting modesty, a convenient humility that was characteristic for their roles. Battisti’s Umberto is persnickety and independent, free of reliance, his small but passionate eyes emitting a profundity of human feeling. His performance never feels false, which amplifies the sense of genuineness present in the film. Such would not be the case with a recognized and celebrated Italian actor from the period.

Battisti’s Umberto finds few joys in the world, save for the loyalty of his mutt Terrier named Flike (a performance that observant viewers will notice is played by two dogs). Like Umberto, the dog has a wise face, following his master-companion with equal parts autonomy and dependence. Leaving Flike under Maria’s care, Umberto, sick with tonsillitis, attends hospital where several days worth of clean sheets and healthy meals do him good. He returns to find his landlady left the door open. Flike has run away, surely wondering where his master disappeared to. With Flike lost, Umberto takes a taxi to the pound. He has no money except for a ₤1,000 note he received from selling some books, so he buys a glass from a nearby vendor to get change for the driver. No matter how poor he may be, money is no longer his concern. Flike is all that matters. He pays the cabbie, smashes the glass, and proceeds to the pound with worried eyes. There Umberto finds the killing room where stray dogs are taken. We can imagine the terror going through his mind. He files a report to an uninterested clerk, and while in line, another pet owner decides to put down his dog, as money is too sparse. Umberto is broke also, but not so much that abandoning his only true companion is an option.

Battisti’s Umberto finds few joys in the world, save for the loyalty of his mutt Terrier named Flike (a performance that observant viewers will notice is played by two dogs). Like Umberto, the dog has a wise face, following his master-companion with equal parts autonomy and dependence. Leaving Flike under Maria’s care, Umberto, sick with tonsillitis, attends hospital where several days worth of clean sheets and healthy meals do him good. He returns to find his landlady left the door open. Flike has run away, surely wondering where his master disappeared to. With Flike lost, Umberto takes a taxi to the pound. He has no money except for a ₤1,000 note he received from selling some books, so he buys a glass from a nearby vendor to get change for the driver. No matter how poor he may be, money is no longer his concern. Flike is all that matters. He pays the cabbie, smashes the glass, and proceeds to the pound with worried eyes. There Umberto finds the killing room where stray dogs are taken. We can imagine the terror going through his mind. He files a report to an uninterested clerk, and while in line, another pet owner decides to put down his dog, as money is too sparse. Umberto is broke also, but not so much that abandoning his only true companion is an option.

Waiting with a small group of concerned pet owners, Umberto watches as trucks arrive, the dog catchers yanking the animals out by a neck restraint like pulling a hooked fish out of water. Flike, of course, arrives on the last truck for a heartrending wave of relief. But more than that, the viewer finally understands how Flike is all there is for Umberto. For cinema, a frequent go-to for depicting human compassion, and furthermore winning an audience’s heart, has always been the love between a dog and its master. From the Walt Disney classic Old Yeller to The Yearling to Samuel Fuller’s White Dog, cinema has defined humanity through our love for dogs. And yet, De Sica’s film does not schematize a warm-hearted dog movie from the beginning like so many others. Flike is present, but recessive to the Umberto character in early scenes, virtually in the background. The dog becomes our connective point to Umberto as he grows more desperate to pay bills, more aware that his position is hopeless. Umberto does not demand the audience’s affections; his persona is written without calculating notes drawing the audience in. Our appreciation for his character comes with time, our natural sympathy growing as we begin to understand just how much this pitiable old man relies on his dog.

As Umberto’s situation worsens, we finally begin to comprehend how potent a need he has for dignity. He wants only to live without fuss—not to make his mark on the world, rather just get along in a respectable fashion. Observing a beggar, he practices sticking his hand out for money. A patron walks by, ready to offer a donation, but Umberto pulls his hand back, pretending to check for rain. He trained Flike to stand on his hind legs, so Umberto positions him upright with his hat in the dog’s mouth and then hides in the distance. People pass bemused by the scene. Alas, no one contributes. Stripped of all he has except Flike, Umberto looks out his window to see train tracks and contemplates suicide. What else is there? His room will be seized by the cruel landlady. To pay his bills he would have to go without food for some time. So he looks for a place to leave Flike, his only remaining responsibility. A local couple’s dog boarding house seems unfit, as the dogs there look unhappy and neglected. He takes Flike to a park where the parents of young Daniela, a girl who has played with Flike before, refuse to take him. All options fall through. Even abandoning the loyal Flike proves futile, as the dog always remains by his side.

As Umberto’s situation worsens, we finally begin to comprehend how potent a need he has for dignity. He wants only to live without fuss—not to make his mark on the world, rather just get along in a respectable fashion. Observing a beggar, he practices sticking his hand out for money. A patron walks by, ready to offer a donation, but Umberto pulls his hand back, pretending to check for rain. He trained Flike to stand on his hind legs, so Umberto positions him upright with his hat in the dog’s mouth and then hides in the distance. People pass bemused by the scene. Alas, no one contributes. Stripped of all he has except Flike, Umberto looks out his window to see train tracks and contemplates suicide. What else is there? His room will be seized by the cruel landlady. To pay his bills he would have to go without food for some time. So he looks for a place to leave Flike, his only remaining responsibility. A local couple’s dog boarding house seems unfit, as the dogs there look unhappy and neglected. He takes Flike to a park where the parents of young Daniela, a girl who has played with Flike before, refuse to take him. All options fall through. Even abandoning the loyal Flike proves futile, as the dog always remains by his side.

In the final scenes, Umberto holds Flike in his arms and prepares to end both their lives by walking onto busy train tracks. As the train approaches, Umberto freezes, but Flike understands and runs away frightened, betrayed. Umberto’s actions have damaged the trust between dog and master, and suddenly ending his misery becomes less important to Umberto than regaining the loyalty of his friend. The old man calls Flike, but he will not come. The dog keeps its distance. Umberto tempts him with a pine cone, rolling it toward him like a ball. At last Flike comes, and with that Umberto realizes his present company is all he needs. And however against neorealistic ideals, however blatantly scheming, this final moment is ingeniously dramatic and utterly sobering. It has become perhaps the most touching, tear-inducing moment in all of cinema.

Upon its release, Umberto D. received international acclaim. The New York Film Critics Circle named it the best foreign film of that year, and it earned nominations for Best Screenplay at the 1957 Academy Awards and for the Grand Prix at Cannes. Italy, however, was not as generous. Because the film tenders an impractically romantic ending from a neorealist’s perspective, the film bombed at the local box office. Politician Giulio Andreotti wrote in Libertà how De Sica’s film failed to “help humanity” by not providing a sensible solution to Umberto’s troubles. If neorealism sought to provide a backbone to browbeaten citizens, then how could an ending so unfeasible resolve anything? After all, what was Umberto going to do after he and Flike prance into the distance during the final frames? Where will their food come from? Where will they sleep? How will he survive? The film’s solution is perhaps not logical in a pragmatist sense, but it feels right.

Upon its release, Umberto D. received international acclaim. The New York Film Critics Circle named it the best foreign film of that year, and it earned nominations for Best Screenplay at the 1957 Academy Awards and for the Grand Prix at Cannes. Italy, however, was not as generous. Because the film tenders an impractically romantic ending from a neorealist’s perspective, the film bombed at the local box office. Politician Giulio Andreotti wrote in Libertà how De Sica’s film failed to “help humanity” by not providing a sensible solution to Umberto’s troubles. If neorealism sought to provide a backbone to browbeaten citizens, then how could an ending so unfeasible resolve anything? After all, what was Umberto going to do after he and Flike prance into the distance during the final frames? Where will their food come from? Where will they sleep? How will he survive? The film’s solution is perhaps not logical in a pragmatist sense, but it feels right.

Indeed, the ending of De Sica’s film does not adhere to the idealized visions for neorealism, complete with societal implications that honor the Italian public during their postwar recovery. In fact, he transcends them completely, marrying the need for an accurate depiction of the then-contemporary working-class with the necessity for escapist sentimentalism and hope. The happy ending might seem formulaic next to the narrative invention of Bicycle Thieves, but by 1952, even neorealism’s structures followed formula. De Sica’s picture combines those two recipes to concoct a potion full of veracity and sorrow and heartbreak and love, without sacrificing his artistic integrity or the natural flow of the film. Dedicated to his father, De Sica’s Umberto D. earns a place among the most life-affirming motion pictures ever made, along with Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru and Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. The film remains an ever-tearful venture for viewers, especially upon subsequent screenings when we see Umberto as kindly and sympathetic throughout, and then remember back to our initial viewing when at first he was merely a face in the crowd. Seeing it again, we remember him and identify with him from the outset. Grasping the change in experiences, De Sica, in turn, humanizes every face in that crowd with his endearing film, and grants them each their dignity in the process.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André and Bert Cardullo. Andre Bazin and Italian Neorealism. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011.

Bondanella, Peter. A History of Italian Cinema. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009.

Ruberto, Laura E. and Kristi M. Wilson. Italian Neorealism and Global Cinema. Detroit: Wayne State Univerity Press, 2007.

Snyder, Stephen and Howard Curle. Vittorio De Sica: Contemporary Perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Wagstaff, Christopher. Italian Neorealist Cinema: An Aesthetic Approach. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review