The Definitives

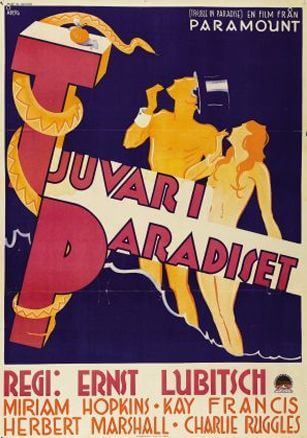

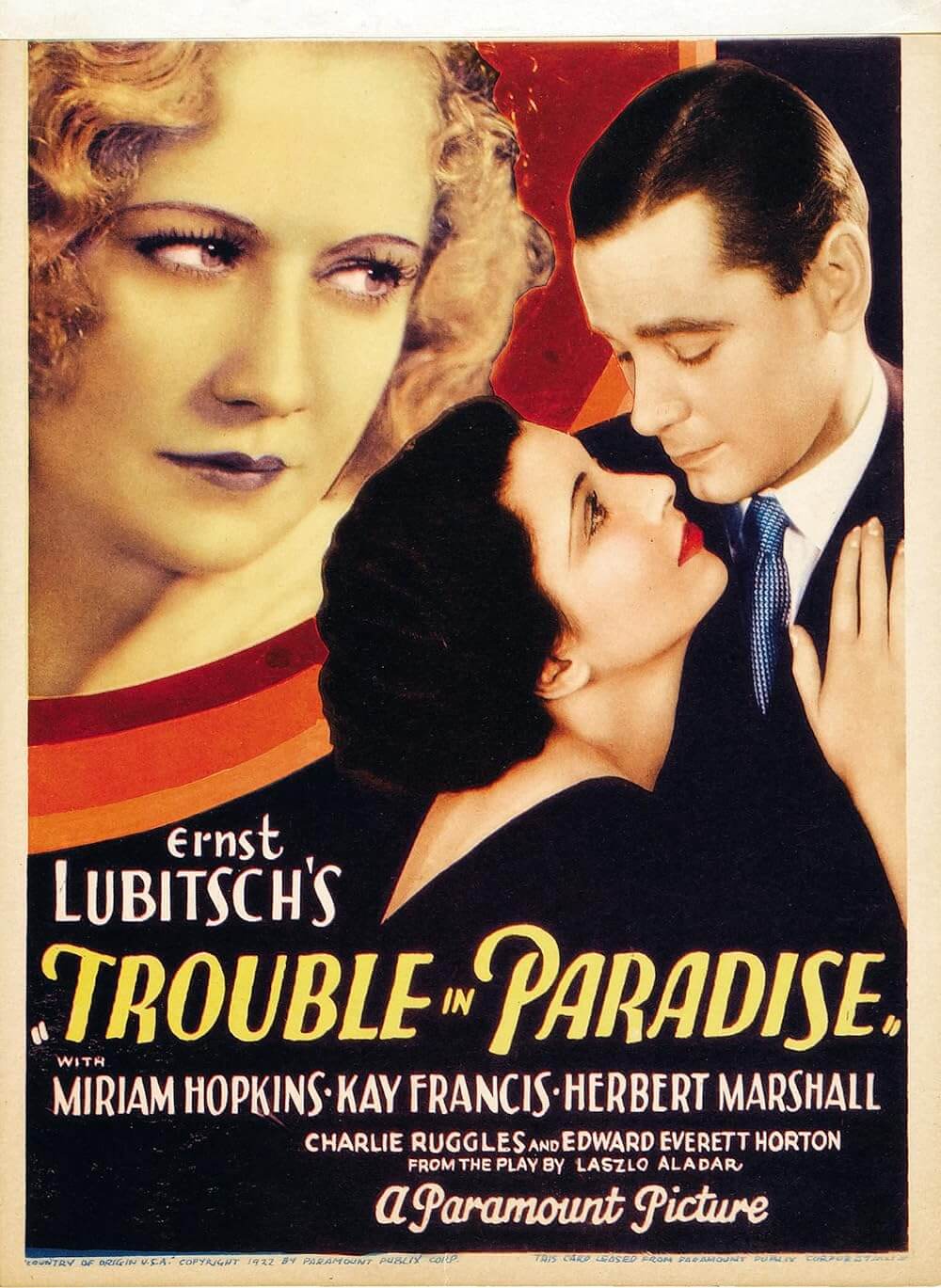

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

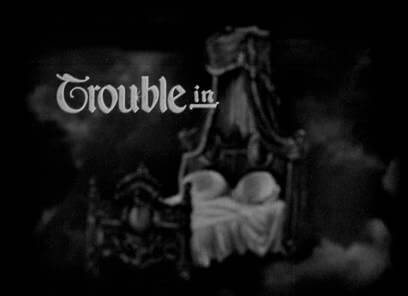

Perhaps the most elegant and sophisticated of all romantic comedy filmmakers, Ernst Lubitsch made blithe comedies about infidelity, satirizing the struggle between desire and romantic idealism. To put it bluntly, Lubitsch made pictures about sex. In a film like Trouble in Paradise, released in 1932, his approach does not engage sex directly; rather, he dances around the subject, such that his exclusions become more important than his disclosures. Lubitsch directs his audience not by pointing to the joke but by waving in the realm of the joke, which is left for us to discover. His audience understands the punchline without it being read to them. From the opening titles, which appear superimposed over a bed, we know the film’s theme concerns the messy quagmire of sex. Trouble in appears first, then the bed behind it, suggesting the title could be Trouble in Bed; finally, Paradise emerges. While this subtle sign could be missed or ignored, for many, it was as stark as the naked form.

Lubitsch was a master of innuendo. Be it a closed bedroom door, curtains pulled shut, or lipstick reapplied, Lubitsch’s delicate inferences say what other films of the period were too afraid to say, and what today’s cinema blurts without an iota of care. His favorite device, a love triangle, drives Trouble in Paradise through its enchanting progression. He begins by establishing his seemingly unshakable romantic couple, who will later be tested by a third party, a common setup for his films. But instead of two idealized figures upset by a clearly devilish third, his leads, Gaston Monescu (Herbert Marshall) and Lily (Miriam Hopkins), are thieves. At their first rendezvous, neither is aware of the other’s pastimes; they keep up the front of two luminaries meeting for a tryst in Venice. As Lily rides her gondola to the hotel, Gaston loses himself in the moonlight and arranges the evening’s provisions with the waiter: “It must be the most marvelous supper. We may not eat it, but it must be marvelous.” Lubitsch’s commentary on social-sexual practices remains critical and comical in the same breath.

Gaston and Lily are joyful in their thievery. Beyond the obvious physical attraction, their expert sleight of hand brings them together. Lubitsch does not show them stealing; instead, with humorous class, reveals that they have stolen. During dinner, Lily confronts Gaston, accusing him of taking a wallet from fellow hotel patron, Monsieur Filiba (Lubitsch regular Edward Everett Horton). He replies to her accusation by calling her a thief, affectionately, of course; she has picked Gaston’s pocket to steal M. Filiba’s wallet herself—the music builds to thrilling highs as Gaston stands, locks the door, and then shakes Lily until the wallet falls from under her dress. Dinner resumes, as does the lovely music. Through pleasantries and endearing compliments, the two reveal their quiet hands have been at work all night: Gaston hands over Lily’s pin, which he removed from her breast; Lily returns Gaston’s watch from inside her purse, having at some point corrected its time. Gaston decides to keep the garter he’s taken without her knowing it. No couple was ever so endearingly meant for each other.

Gaston and Lily are joyful in their thievery. Beyond the obvious physical attraction, their expert sleight of hand brings them together. Lubitsch does not show them stealing; instead, with humorous class, reveals that they have stolen. During dinner, Lily confronts Gaston, accusing him of taking a wallet from fellow hotel patron, Monsieur Filiba (Lubitsch regular Edward Everett Horton). He replies to her accusation by calling her a thief, affectionately, of course; she has picked Gaston’s pocket to steal M. Filiba’s wallet herself—the music builds to thrilling highs as Gaston stands, locks the door, and then shakes Lily until the wallet falls from under her dress. Dinner resumes, as does the lovely music. Through pleasantries and endearing compliments, the two reveal their quiet hands have been at work all night: Gaston hands over Lily’s pin, which he removed from her breast; Lily returns Gaston’s watch from inside her purse, having at some point corrected its time. Gaston decides to keep the garter he’s taken without her knowing it. No couple was ever so endearingly meant for each other.

Lubitsch takes us to Paris next to introduce Colet and Company, a French perfumer led by extravagant figurehead Madame Mariette Colet (Kay Francis). At the opera, her ₣125,000 jewel-encrusted handbag is pilfered. The crook goes unseen by Colet and the film’s viewers, but we have our suspicions. Rather than take the considerably less street value, Gaston, ever the thief, returns the purse for Colet’s publicized reward. Sparks fly as he offers Colet sound makeup advice, impeccable flirtatious tact, and dispels unwanted suitors, including The Major (Charles Ruggles). In short order, Gaston accepts the opportune position of Madame Colet’s personal secretary in her swank Art Deco home (with lavish sets and accessories designed by Hans Dreier), giving this master thief access to her personal safe and company-wide resources. But with every step Gaston takes toward Colet’s fortune, he finds himself falling in love with her. Meanwhile, Lily takes a job as Gaston’s secretary, unintentionally freeing him up for Colet’s more personal needs. Exaggerated to comic extremes, Gaston and Mariette seem to melt into each other during every conversation, just as Gaston and Lily did at their initial dinner. They never feel out of sync; rather, they know each other implicitly and lovingly scold one another with wit and composure.

In due course, M. Filiba, a chance member of Mariette’s entourage, (finally) recognizes Gaston’s notorious face. And so, Gaston’s game must end quickly while Colet remains none the wiser. Preparing for a clean getaway, Lily packs while Gaston wraps up office errands, but Colet slows their urgent dash with her continued courting of Gaston. She begins to take off her jewelry pre-coitus in Gaston’s office bedroom and asks, “When a lady takes her jewels off in a gentleman’s room, where does she put them?” Gaston replies, “Well, on the… on the night table.” Colet smiles, “But I don’t want to be a lady.” Sexual ruminations aside, Gaston chooses Lily, with a heartbroken concession from Madame Colet. Lily is the right choice for love, while Madame Colet is a dreamlike sexual ideal. And to be sure, our lover-thieves walk away with Colet’s cash, purse, and pearls, untouched by the law and unscathed in their love for one another. Lubitsch’s brand of mutual sexual understanding and knowing sophistication was often called “The Lubitsch Touch”—an endearing, if not limited and sometimes vaguely used term, as Lubitsch could be much more than sophisticated. Nevertheless, of his own work, Lubitsch wrote of Trouble in Paradise in 1947, saying, “As for pure style, I think I have done nothing better or as good.”

Working in Hollywood throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the German-born director became one of the first in a series of European filmmakers to leave their homeland and bring an alternative sensibility to America’s otherwise puritanical model. Making his acting debut in 1911 at the Max Reinhardt Theater Company, the Berlin-born tailor’s son would direct and star in a series of short screen comedies before moving to full-length features. After he made several successful large-scale romances as a full-time director, Mary Pickford contracted Lubitsch to join her in Hollywood to direct her in Rosita (1923), which Pickford also produced. Still, even with that film’s success, Pickford and Lubitsch clashed and never worked together again. Early in his Hollywood career, Lubitsch was influenced by Charles Chaplin’s dramatic turn on A Woman of Paris (1923) and made unsuccessful dramatic efforts such as The Patriot (1928) and The Man I Killed (1932). Later, he found his niche in musicals and romantic comedies, exploring the sexual goings-on of swindlers, thieves, spies, and bohemians, all of whom he showed as a refined contrast to the often dopey regulars in his films. He never went back to drama.

Working in Hollywood throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the German-born director became one of the first in a series of European filmmakers to leave their homeland and bring an alternative sensibility to America’s otherwise puritanical model. Making his acting debut in 1911 at the Max Reinhardt Theater Company, the Berlin-born tailor’s son would direct and star in a series of short screen comedies before moving to full-length features. After he made several successful large-scale romances as a full-time director, Mary Pickford contracted Lubitsch to join her in Hollywood to direct her in Rosita (1923), which Pickford also produced. Still, even with that film’s success, Pickford and Lubitsch clashed and never worked together again. Early in his Hollywood career, Lubitsch was influenced by Charles Chaplin’s dramatic turn on A Woman of Paris (1923) and made unsuccessful dramatic efforts such as The Patriot (1928) and The Man I Killed (1932). Later, he found his niche in musicals and romantic comedies, exploring the sexual goings-on of swindlers, thieves, spies, and bohemians, all of whom he showed as a refined contrast to the often dopey regulars in his films. He never went back to drama.

When Lubitsch arrived in Hollywood, Cecil B. DeMille and D.W. Griffith ruled the studios, while new European filmmakers such as Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, and Jacques Tourneur were reinventing the way American films were made. Lubitsch preceded his European contemporaries, innovating on American genres and adding European panache. His films were familiar to Americans, yet wholly exotic with European airs. Although the genre he’s known for today is the romantic comedy, he began by single-handedly inventing the musical. Lubitsch filmed The Love Parade in 1929, stylistically following German operettas he saw during his youth—it was Hollywood’s first all-sound song-and-dance extravaganza. Monte Carlo followed in 1930, The Smiling Lieutenant in 1931 (his best musical), and One Hour with You in 1932. Through these whimsical and ever-lovable films, from which Lubitsch-created musical tropes are still borrowed today, the director molded the future screen careers of French charmer Maurice Chevalier and crowned “Queen of Hollywood” Jeanette MacDonald. As a worker, he brought in his productions on or under budget, jealously adhered to the script, and upheld an efficiency that signaled his dependability to studio executives. With an unchallenged career of commercial and artistic successes—among them The Marriage Circle (1923), Design for Living (1933), The Merry Widow (1934), and The Shop Around the Corner (1946)—he worked for Paramount (he ran the studio briefly in 1929 as production head) and Warner Bros., earning himself unheard of widespread acclaim and respect.

All the while, Lubitsch slipped characters with questionable moral values past censors, presenting them as cultured and well-mannered. Despite their outward flaws, he never holds morals over them, nor does he excuse their behavior. In this sense, his films were realistic fantasies. And yet, this dynamic would elude Lubitsch in his personal affairs. His longtime collaborator Samson Raphaelson called him “almost naïve” and “as an artist shrewd, as a man simple.” No matter how effortless and charming his films were, Lubitsch’s personal life was a romantic tragedy. Maybe his naïveté attracted his two wives: one had an affair with his best friend; another married Lubitsch for his money and left him after she bore his only child, Nicola. His friends said he was overly sensitive about his appearance, despite his charisma and geniality being well known and cherished throughout Hollywood. However complex his life, his films were his legacy. At his funeral, Billy Wilder commented, “No more Lubitsch.” William Wyler responded, “Worse than that, no more Lubitsch films.”

Trouble in Paradise was Lubitsch’s first non-musical romantic comedy, adapted from a Laszlo Alada play by Raphaelson, screenwriter of Hollywood’s first renowned talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927). As the director’s greatest and most frequent contributing writer, Raphaelson penned the Lubitsch staples The Merry Widow, The Shop Around the Corner, and Heaven Can Wait (1943), adorning them all with unparalleled intelligence and humor. Understanding cinematic clichés and working with his director to avoid them at all costs, Raphaelson helped pioneer Lubitsch’s stark innovations on the typical American narrative structure. His screenplay’s tricks of metaphor and tender cynicism were emboldened by Lubitsch’s near-invisible direction. Every line has a double meaning or redirection, resulting in deft surprises and inevitable turns. Watch when Colet rejects her prospective beau, M. Filiba, with breezy abandon when she says, “Marriage is a beautiful mistake which two people make together… But with you, François, I think it would be a mistake.” Raphaelson brought words to Hollywood with The Jazz Singer; he perfected those words in his dialogue for Trouble in Paradise.

Trouble in Paradise was Lubitsch’s first non-musical romantic comedy, adapted from a Laszlo Alada play by Raphaelson, screenwriter of Hollywood’s first renowned talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927). As the director’s greatest and most frequent contributing writer, Raphaelson penned the Lubitsch staples The Merry Widow, The Shop Around the Corner, and Heaven Can Wait (1943), adorning them all with unparalleled intelligence and humor. Understanding cinematic clichés and working with his director to avoid them at all costs, Raphaelson helped pioneer Lubitsch’s stark innovations on the typical American narrative structure. His screenplay’s tricks of metaphor and tender cynicism were emboldened by Lubitsch’s near-invisible direction. Every line has a double meaning or redirection, resulting in deft surprises and inevitable turns. Watch when Colet rejects her prospective beau, M. Filiba, with breezy abandon when she says, “Marriage is a beautiful mistake which two people make together… But with you, François, I think it would be a mistake.” Raphaelson brought words to Hollywood with The Jazz Singer; he perfected those words in his dialogue for Trouble in Paradise.

Lubitsch films often involve delivering a soft blow to the upper classes; he pokes fun at the bourgeoisie, their frequent promiscuity, and their recklessness with money. Sexual crassness serves as his tool to chip away at the prestige of “nobles,” bringing them down a notch, humanizing them, even depicting them as childish. In his silent picture The Oyster Princess (1919), the title character (Ossi Oswalda) vows to smash every bit of furniture and decoration in her house until she’s married; after she’s finally married, the uninvolved Oyster King (Victor Janson) tiptoes downstairs like a cartoon to peep grotesquely through his daughter’s keyhole, hoping to find her consummating her new marriage, perhaps giving him something to be “impressed” with. Or look at Gene Tierney’s parents (Eugene Pallette and Marjorie Main) in Lubitsch’s late joy Heaven Can Wait. They bicker childishly over the funny papers, forcing their server to relay messages between them on opposite ends of a comically elongated dinner table. Lubitsch elevates his audience by making the rich absurd to humanizing extremes.

Following this pattern, Trouble in Paradise offers an escapist romantic fantasy with then-modern relevance by addressing issues plaguing the world of 1932, specifically the nationwide disenchantment with The Great Depression. Lubitsch shows us how absurd the world looks by raising us above it. With well-to-do thieves as his heroes, he implies that Madame Colet deserves to be robbed. After all, look at the way she spends money needlessly on a handbag. At one moment, ₣3,000 is too much for one purse; the next moment, ₣125,000 seems like a bargain for the attention it will bring. Of course, the thief-lovers, as well as the greed of Madame Colet, become appealing for Depression-era audiences by way of monetary appeal—their ability to steal, or simply have wealth, lures victims of the recession. Gaston even refers to himself as a member of the “nouveau poor,” identifying himself with his contemporary audience. Not even the romantic promise of Venice is safe from the director’s critical eye. Trouble in Paradise opens with a garbage man emptying trash onto a gondola, bellowing a sonata from a boat traditionally reserved for aristocrats.

Indeed, the director chose targets as closely as his subjects and themes. Another of Lubitsch’s masterpieces is To Be or Not to Be, the dark wartime satire he hoped would give Hitler a much-needed kick in the pants. Filmed in the latter part of 1941, just before America entered World War II, the film centers on an acting troupe that outwits numbskull Nazis in occupied Warsaw. Jack Benny and Carole Lombard (in her last screen performance) star in this provocative attack on Hitler’s regime—as directly referential as Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940)—that says more than Hollywood was willing to say before the war began. Felix Bressart’s character goes as far as to recite Shylock’s famous “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech from The Merchant of Venice; a German of Jewish background, Lubitsch sought to defend his beliefs. Nevertheless, To Be or Not to Be was released in March of 1942, receiving an awkward response given the political climate. Attitudes toward the picture would lighten as years passed, and the film is now acknowledged as one of the cinema’s great comic satires.

Indeed, the director chose targets as closely as his subjects and themes. Another of Lubitsch’s masterpieces is To Be or Not to Be, the dark wartime satire he hoped would give Hitler a much-needed kick in the pants. Filmed in the latter part of 1941, just before America entered World War II, the film centers on an acting troupe that outwits numbskull Nazis in occupied Warsaw. Jack Benny and Carole Lombard (in her last screen performance) star in this provocative attack on Hitler’s regime—as directly referential as Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940)—that says more than Hollywood was willing to say before the war began. Felix Bressart’s character goes as far as to recite Shylock’s famous “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech from The Merchant of Venice; a German of Jewish background, Lubitsch sought to defend his beliefs. Nevertheless, To Be or Not to Be was released in March of 1942, receiving an awkward response given the political climate. Attitudes toward the picture would lighten as years passed, and the film is now acknowledged as one of the cinema’s great comic satires.

Never forget that Lubitsch has made us fall for criminals in Trouble in Paradise. Each member of Lubitsch’s love triangle is a thief, a swindler, and a superficial artistocrat, but they remain honest about their positions. None are hypocrites, especially when they flirt; they at once realize the potential disaster but follow their loins nonetheless. Lubitsch walks us through the gate into an affectionate and sexual dream world, the consequences of which are less important than the acts themselves. Generally speaking, Pre-Code cinema of this kind contains a surprising amount of sexual content, which seems uncharacteristic given popular contemporary views that classical cinema is somehow stuffy or sexually repressed. Rather, DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932), for example, made the same year as Trouble in Paradise, is pointedly liberated, depicting Orientalized lesbians, orgies, and nude bathing scenes amid Roman courts. Such blatant signs were described as “immoral,” just as some Prohibition-era gangster pictures (such as Howard Hughes’ Scarface, also 1932) were said to glorify violence and gangsterism. Public protests over Hollywood’s growing indecency in entertainment media fuelled the creation of the Production Code (or Hays Code), established on March 31st, 1930. Enforcement of the Code began on July 1st, 1934. After this date, all films would require a certificate of approval before release, issued by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (or MPPDA, later MPAA and then MPA).

Released a year-and-a-half before the Production Code’s imposition on Hollywood, Lubitsch slipped Trouble in Paradise through the cracks with intact riffs on so-called sexual swapping and criminality. The Code demanded that such immoral behavior be punished, whether by law, by fate, or by God. But Gaston and Lily, thick as the thieves they are, remain criminals and, most significantly, they get away with it. When the film ends, their crimes are unpunished; even Gaston’s intended infidelity is excused. In fact, we are overjoyed in the finale when Gaston and Lily pinch Colet’s pearl necklace, jewel-coated purse, and ₣100,000 worth of incidental cash. But because of these details, Trouble in Paradise failed to receive re-release approval under Hays Code mandates after 1934 due to its “depraved” content. It was not seen again until its welcome 1968 revival, when a new wave of film students sought examples of liberated sexual politics in film. This is the case with several early Lubitsch romantic comedies. Consider Design for Living (1933), a film that begins and ends with the notion of a functioning and healthy threesome—not even years later, in more liberal cinematic time,s did François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) or Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) have the bravery to suggest such a thing.

Now imagine if Lubitsch released Trouble in Paradise in 1935 under Production Code regulation. “Different” hardly describes the resulting hypothetical product. Of course, M. Filiba would still recognize Gaston Monescu straightaway, while the justly moral Madame Colet would begrudgingly concede that the police take her budding lover to jail. No doubt Gaston would be imprisoned for his robberies, and Lily, too, for her part in the con. Perhaps this version would end with our couple jailed in side-by-side cells, exchanging flowery dialogue through prison bars, rather than driving away in a getaway car. Fortunately, the film was released at the height of Lubitsch’s artistic prowess, allowing Lubitsch’s half-nefarious, half-endearing characters to remain, in their humanness and, curiously, in their exaggerated but affable flaws, free. Of all Lubitsch’s pictures, this one best explores the direct theme of romance, which stands as a symbol of sexual freedom; he was careful to separate these concepts, with one serving as a nod to the other in the cleverest of ways.

Now imagine if Lubitsch released Trouble in Paradise in 1935 under Production Code regulation. “Different” hardly describes the resulting hypothetical product. Of course, M. Filiba would still recognize Gaston Monescu straightaway, while the justly moral Madame Colet would begrudgingly concede that the police take her budding lover to jail. No doubt Gaston would be imprisoned for his robberies, and Lily, too, for her part in the con. Perhaps this version would end with our couple jailed in side-by-side cells, exchanging flowery dialogue through prison bars, rather than driving away in a getaway car. Fortunately, the film was released at the height of Lubitsch’s artistic prowess, allowing Lubitsch’s half-nefarious, half-endearing characters to remain, in their humanness and, curiously, in their exaggerated but affable flaws, free. Of all Lubitsch’s pictures, this one best explores the direct theme of romance, which stands as a symbol of sexual freedom; he was careful to separate these concepts, with one serving as a nod to the other in the cleverest of ways.

In a Lubitsch film, what might be considered brutal honesty translates into endearing candor. When Lily tells Colet that her mother is dead, Mariette replies, “That’s the trouble with mothers. First, you get to like them. Then they die.” On the one hand, she jokes about her mother’s death; on the other, she refuses to cut her workers’ salaries (another important aspect of her character to Depression-era audiences). No one apologizes for their feelings in an Ernst Lubitsch film. In this romanticized Paradise, Gaston never has to deny his feelings for Colet to Lily, nor does Colet deny her intentions toward Gaston. Everyone participates in The Game of Sex, and all parties are well aware of the rules before the whistle blows and the game begins. For its honesty and unrestrained frankness about relationships and sex, Trouble in Paradise is a delightful screen fantasy, and a rare one in which men and women can give and receive “love”—elements of an adult, sophisticated view toward romance and a key characteristic of “The Lubitsch Touch.”

Bibliography:

Eyman, Scott. Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review