The Definitives

Toy Story

Essay by Brian Eggert |

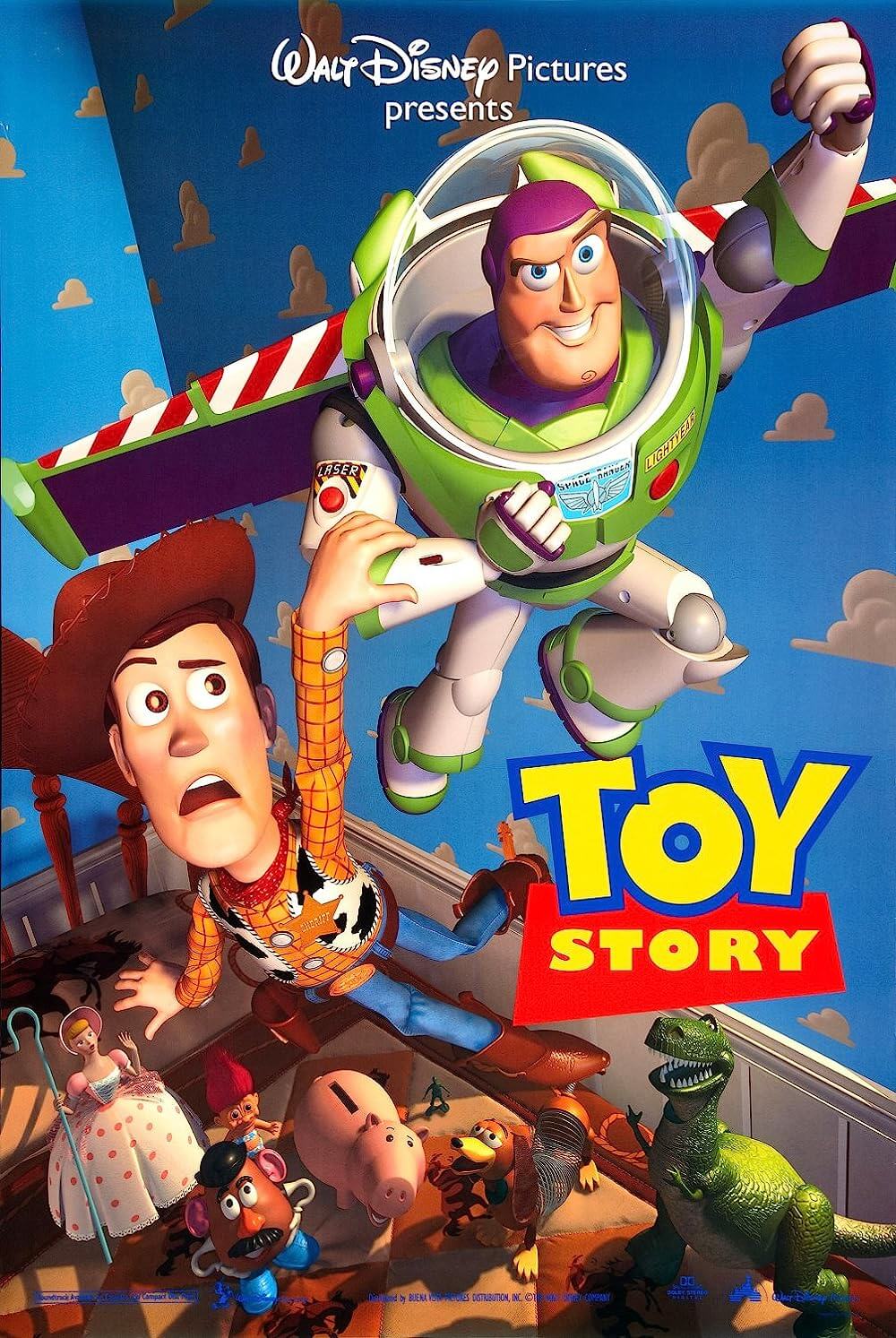

In both its narrative and production, the basis of Pixar’s Toy Story contains an intriguing metaphor whereby the film mirrors Pixar itself. The animation studio employs computers, inanimate and seemingly lifeless tools, to fabricate and bring to life worlds of affecting drama, witty comedy, and endless possibility. Toy Story does much the same by bringing life to inanimate objects, namely children’s toys, through a lighthearted tale that strikes no end of emotional chords. How fortuitous, and rather wonderful, that Pixar’s first film and their own story should share this strange alignment, together offering an integrated account of a small, bright hero entering a much larger world from the unlikeliest of origins. As a piece of history, the film presents several firsts: the first feature by Pixar; the first grand success of many in a track record that seems almost too good to be true; the first fully computer-animated film. But the magic of Pixar began to flicker long before Toy Story, beginning with the company’s experimental promotional short films and television commercials from its director John Lasseter, all completed on computers, without use of cameras or paint brushes. The long road from Pixar, Inc., the small computer hardware outfit established in 1979, to the animation studio known today was anything but graceful, and the company nearly crumbled more than once. However, Lasseter, as well as other key figures in the early incarnation of Pixar, maintained fixed on the goal of combining computer technology with traditional hand-drawn animation principles. Their efforts culminated with the glorious achievement of Toy Story, which would make history both by establishing Pixar as the standard for creative storytelling, but also by proving computers a valid instrument in the cinematic toolkit.

The film considers the perspective of children’s toys, whose walking and talking existence concerns only being played with by their owner. In the room of youngster Andy, the top toy is the cowboy plush Woody, who presides over the others as Andy’s favorite. Together, they have a small community, there for Andy whenever he needs them. Woody’s place as the top-tier toy is threatened on the boy’s birthday, when Andy receives ‘space ranger’ Buzz Lightyear as a gift, a more advanced action figure with a light-up laser and spring-action wings. At first, Buzz believes himself to be the actual Buzz Lightyear and not a toy; this infuriates Woody, but the rest of the toys are captivated with Buzz’s space-aged toy features. Most importantly, Andy loves him. Resenting Buzz for quickly taking his place as Andy’s favorite, Woody attempts to hide Buzz so that he can join Andy on an outing, just the two of them. In doing so, he inadvertently knocks Buzz out of Andy’s bedroom window, and the other toys accuse him of foul play. Before the mob of fellow toys can deal with Woody, Andy takes him to the car for the ride to Pizza Planet, and there he finds Buzz alive. The confused Buzz, still believing himself a bona fide space ranger, wants only to return to his home planet, and so when they arrive at the sci-fi themed pizzeria, he crawls into a crane toy machine shaped like a spaceship. Woody follows, and both are captured, or won, by Andy’s next-door neighbor, the sadistic Sid, who gets his kicks by demolishing his toys with fireworks. Doomed to be blown up by Sid and unable to get help from Andy’s other toys, Woody and Buzz must escape. But during their getaway, Buzz sees a toy commercial on television for a Buzz Lightyear action figure, which sends him into catatonia upon realizing that he too is just a toy. To snap him out of it, Woody must convince Buzz of the joys in being a toy, particularly for an owner like Andy. Once Buzz finally accepts his standing, he and Woody narrowly escape Sid’s capture, only to find Andy has just left the home in a planned move to a new house. Racing to return to their owner, Woody’s name is cleared among Andy’s other toys, and Woody and Buzz find a happy equilibrium as Andy’s favorites.

Long before these delightful toy characters were ever conceived, the film’s director had to master the art of animation in the untried medium of computer technology. Straight out of high school, where he had already declared his desires to become an animator, John Lasseter attended the California Institute of the Arts (or CalArts), a school that was an initiative of Walt Disney himself, for character animation. There, Lasseter could embrace his passion for animation under the tutelage of Disney animators such as Kendall O’Connor (art director on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) and Elmer Plummer (character designer on Dumbo), while learning alongside peers such as Brad Bird (director of The Incredibles and Ratatouille). Lasseter was offered a position at Disney in his junior year, but opted to finish school until graduating, when, in 1979, he took a position with Disney as junior animator. But Lasseter came to Disney in one of their least productive, most un-magical periods. Working on The Fox and the Hound and the short Mickey’s Christmas Carol, he was invited by friends working on the upcoming release of Tron to prescreen some computer animated footage. Upon seeing rough imagery of the film’s light cycles racing, Lasseter was struck with the idea of computer technology merging with Disney character animation. With a small budget, Lasseter was allowed to create a thirty-second test of his idea—a scene from Maurice Sendak’s book Where the Wild Things Are of a boy racing through his house with a dog following behind him—with computer-animated backgrounds and hand-drawn characters. His idea was rejected, and for what was considered out-of-line forward-thinking, he was fired.

Long before these delightful toy characters were ever conceived, the film’s director had to master the art of animation in the untried medium of computer technology. Straight out of high school, where he had already declared his desires to become an animator, John Lasseter attended the California Institute of the Arts (or CalArts), a school that was an initiative of Walt Disney himself, for character animation. There, Lasseter could embrace his passion for animation under the tutelage of Disney animators such as Kendall O’Connor (art director on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) and Elmer Plummer (character designer on Dumbo), while learning alongside peers such as Brad Bird (director of The Incredibles and Ratatouille). Lasseter was offered a position at Disney in his junior year, but opted to finish school until graduating, when, in 1979, he took a position with Disney as junior animator. But Lasseter came to Disney in one of their least productive, most un-magical periods. Working on The Fox and the Hound and the short Mickey’s Christmas Carol, he was invited by friends working on the upcoming release of Tron to prescreen some computer animated footage. Upon seeing rough imagery of the film’s light cycles racing, Lasseter was struck with the idea of computer technology merging with Disney character animation. With a small budget, Lasseter was allowed to create a thirty-second test of his idea—a scene from Maurice Sendak’s book Where the Wild Things Are of a boy racing through his house with a dog following behind him—with computer-animated backgrounds and hand-drawn characters. His idea was rejected, and for what was considered out-of-line forward-thinking, he was fired.

Around this time, Steve Jobs and Edwin Catmull had founded Pixar, Inc. as a computer subdivision to George Lucas’ film production company Lucasfilm. Lasseter found employment there, where he was allowed to implement classic animation principles to a computer animation in a short called André and Wally B, being about a boyish hero who escapes the sting of a pesky bee. Using the same type of rudimentary computer systems that helped generate cinema’s first piece of computer animation in the “Genesis sequence” of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Lasseter makes simple shapes come to life through his signature faultless character design. Although Lucas himself was not impressed with the result and ironically failed to see the significance of Lasseter’s breakthrough (ironic because of Lucas’ reliance on computer animation later in his career), others in the field saw the same boundless potential for the new medium that Lasseter did. But because, at the time, Lucas, as well as legendary Disney animator and animation author Frank Thomas, dispelled even the possibilities of computer animation, suggesting it lacked the nuances of hand-drawn animation, Lasseter’s victory went unnoticed in the film industry.

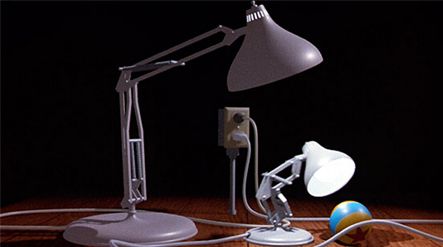

When Pixar, Inc. was purchased from Lucasfilm by Steve Jobs and the Pixar employees in 1986, the “Inc.” was dropped for purposes of singularity. The company’s first and primary goal under Jobs was to sell the Pixar Image Computer, which enhanced and analyzed images, such as rendering a 3-D mock-up of 2-D CAT scan. Meanwhile, Lasseter and other animators proceeded to work on short films, such as the one-minute-and-thirty-second gem Luxo, Jr., which later served as the basis for the Pixar Animation Studios logo. Luxo, Jr. follows father and son lamps who play together with a rubber ball; Luxo Jr. bounces on the small ball, pops it, and then scuttles off to find another, larger ball to play with—one he surely will not break. Luxo Sr. shakes his head in fatherly bewilderment. After previewing Luxo, Jr. at the annual convention SIGGRAPH (Special Interest Group on GRAPHics and Interactive Techniques), Lasseter and Pixar received praise for achieving both photorealism and emotional realism through computer animation. Lasseter had even succeeded in besting Walt Disney, who claimed that inanimate objects could not be animated for dramatic effect, only comic effect. Lasseter proves otherwise. Why else are we sad when Luxo Jr. shamefully hops away after his father shames him for bursting his toy?

Pixar’s next breakthrough was the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), developed for Walt Disney Company to scan drawings of characters, add color, insert them onto composed backgrounds along with other layers of animation, and then render a completed frame onto film. After a successful test on The Little Mermaid in 1988, every Disney animated feature, though hand-drawn, was brought together with Pixar’s CAPS computer system. It allowed animators to work outside of the established boundaries, which limited them to five cell layers of animation per frame. With these boundaries no longer a hindrance, animators were free of budgetary or scheduling concerns, allowing more complicated sequences and shots to be completed in a shorter span of time. After the first all-CAPS produced feature, The Rescuers Down Under in 1990, Disney films in what has been called the 1990 Disney Renaissance—with titles like Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King—were more visually stunning than ever. Although, Disney kept their use of the CAPS system under wraps in the public eye, so as not to take away from their legacy of hand-drawn craftsmanship.

With the later shorts Red’s Dream and eventually Tin Toy also receiving high praise at SIGGRAPH, it became evident to all at Pixar that they would rather be making movies than producing computer technologies. This was all the more solidified when Tin Toy won a 1988 Academy Award for Best Animated Short. Lasseter’s shorts were gaining public attention now, and he followed Tin Toy with Knick Knack, a pure comedy inspired by the animated shorts of director Tex Avery. In the short film, a snowman in a snowglobe shares shelf space with bric-a-brac from assorted worldwide hot spots, including a busty ornament donning a bikini. She waves him over, and the snowman attempts, albeit ineffectively, to escape his globe and reach her. The original version featured finger-snapping music by then-popular singer Bobby McFerrin, but was eventually re-tooled for a home video release, both in the music selection and in the female figurine’s exorbitant bust size. To gain revenue for their eventual plan of making a feature film, Pixar turned Lasseter’s talents as an Oscar-winning short film director onto the realm of television commercials. He completed ads for Tropicana orange juice, Pillsbury, Trident gum, and Volkswagen, among many others through the mid-1990s, upwards of fifteen commercials annually, creating an average income of $2 million per year for Pixar. Meanwhile, their hardware sales continued to diminish, making the possibility and even necessity of a feature film ripe for implementation. Financially, Pixar was in ruins and continued to lose money, even after Jobs had restructured the company, laid off nearly half of Pixar’s 72 employees, and maintained an unwavering dedication to their hardware’s sales.

When Disney approached Pixar to make a feature film in the company’s commended computer animation, the fit seemed natural, as Walt Disney Company was then considered the stand-alone king of the medium. However, because many of Pixar’s animators had left Disney due to the reported tyrannical treatment of their animating staff under president Jeffrey Katzenberg, it took some convincing that Katzenberg’s influence would not impede the production or sway Pixar’s goals for the feature. After months of negotiations and failed proposals with other Hollywood studios about cutting a feature film deal, Disney and Pixar finally agreed on the financial terms and the final contract was all but signed. And in March of 1991, Lasseter, Peter Docter (Monsters, Inc.), and Andrew Stanton (WALL·E) completed a treatment of Toy Story, a take on the life of toys, a topic made in part because their plastic compositions are easier to animate than human flesh. Only this early version followed the tin musician character from the Oscar-winning Tin Toy and his ventriloquist dummy partner called “The Dummy” on an adventure through the outside world, striving to get home and be played with. Indeed, the treatment shared little resemblance to the finished film.

The script for the film as seen today came about through several treatments and a seemingly endless series of drafts that passed through the hands of multiple writers (including Lasseter, Joel Cohen, Alex Sokolow, Joe Ranft, and Joss Whedon). After endless months of writing, the script was approved by Katzenberg in 1993. Now that the script was completed, Lasseter began considering two things: music and voices. For music, Lasseter wanted to avoid making the film a musical with the Disney tradition of “I want” songs filling the soundtrack. Randy Newman agreed to score the film, his first, and wrote original songs that perfectly capture every emotional keystone in the narrative. The best of them, “You’ve Got a Friend in Me”, remains as iconic today as Casablanca’s “As Time Goes By”.

The script for the film as seen today came about through several treatments and a seemingly endless series of drafts that passed through the hands of multiple writers (including Lasseter, Joel Cohen, Alex Sokolow, Joe Ranft, and Joss Whedon). After endless months of writing, the script was approved by Katzenberg in 1993. Now that the script was completed, Lasseter began considering two things: music and voices. For music, Lasseter wanted to avoid making the film a musical with the Disney tradition of “I want” songs filling the soundtrack. Randy Newman agreed to score the film, his first, and wrote original songs that perfectly capture every emotional keystone in the narrative. The best of them, “You’ve Got a Friend in Me”, remains as iconic today as Casablanca’s “As Time Goes By”.

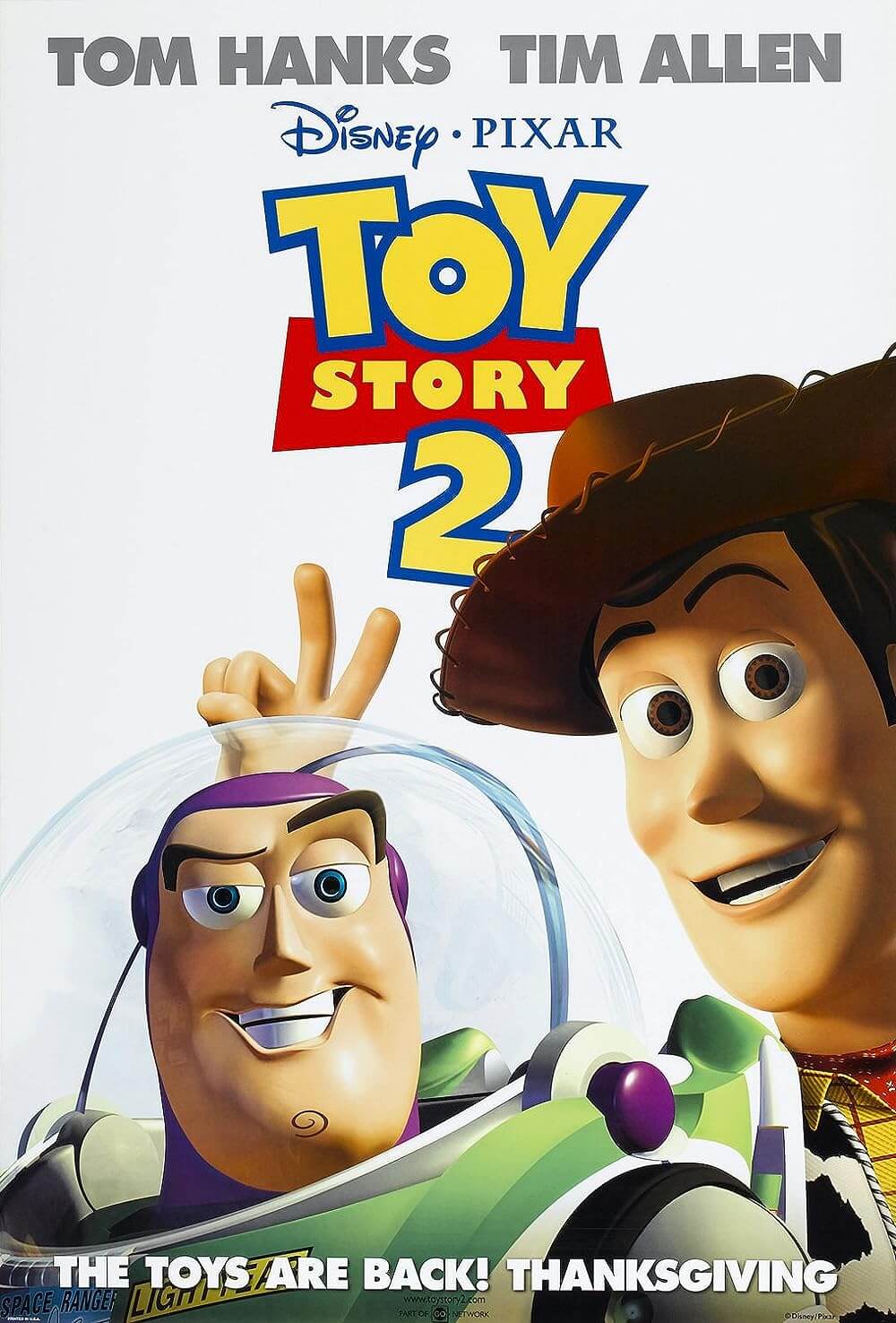

Lasseter sought out Tom Hanks to voice the role of Woody, because he saw in Hanks an ability to make any emotion likable. Consider the scene in A League of Their Own when Hanks famously shouts at a wailing female baseball player “There’s no crying in baseball!” and yet remains funny for his frustration. When Woody is no longer the number-one toy for his owner Andy, replaced by Buzz, the hero behaves quite badly in his low, yet Hanks keeps the character enduring. Hanks, who had not yet won an Oscar for, but had just completed filming Philadelphia, signed onto the film after being wowed by an animated presentation the Pixar staff had prepared that mixed Woody’s character from the “Not the car! Don’t eat the car!” scene from Hanks buddy-cop-dog movie Turner & Hooch. For Buzz, Lasseter wanted Billy Crystal, who, upon imagining the actor’s voice with the character’s face and personality, would not have worked in the role. Luckily, Crystal turned the part down; although, after seeing the finished film, Crystal said it was a huge mistake and gladly accepted the role of the one-eyed monster Mike Wazowski in Monsters, Inc. Instead, Lasseter turned to Tim Allen, who had demonstrated Buzz’s brand of misplaced male confidence on his Disney-produced television show Home Improvement. He brought that same self-assuredness to the role, yet in the recording studio helped change the character from one of a superhero to a “well-trained cop” with an appropriate dose of humanity.

Despite these progressions on the production, and a very rough draft of the film completed, the production was shut down in late 1993 after Disney executives watched the unfinished cut and were unmoved. Disney wanted a new script and production could not resume until it was completed and approved. The Pixar staff still refers to this day as Black Friday, as the future of their entire company rested with completion and success of Toy Story. The problems in the script at this stage were evident, primarily because of the Woody character, who the team had written as the selfish, dogmatic overlord of Andy’s toys. The character was hardly likable. He verbally abused the other toys, and he would later intentionally push Buzz out of the window—whereas in the completed film Buzz falls out of the window by accident, though Woody is to blame for driving the incident. When the writers corrected these problems, the script was eventually approved and Disney issued a meager budget of $17.5 million to complete.

110 animators were paid middling salaries for their work, but they enjoyed being a part of the first fully computer-animated film. Every shot passed through eight teams of production, accounting for layout, color, lighting, framing, texture, shading, the illusion of camera movement, and pure animation by Pixar’s team of animators. An old adage states that “an animator is just an actor with a pencil.” If this is the case, Pixar’s animators are superb actors each. The animators inspirit the characters, in particular because Pixar already had a reputation attracting the best animators in the business, experienced or fresh out of CalArts. Moreover, Lasseter resisted assigning a single animator a single character through the entire feature, which is Disney’s practice. Every Pixar animator was assigned a shot (a few seconds of screen time) rather than a character, so every animator must be well versed in every character onscreen to complete their assigned scene. In all, there were seventy-seven minutes of animation and 1,561 shots used for the production. For the entire staff of animators to grasp every character in any given shot requires an extensive synchronization between animators and a profound understanding of character and story for all working on the production. This uniformity is unparalleled by any studio in the animation business.

Through this process, the budget for Toy Story increased by several million that was only in part covered by Disney, who was more concerned about their own impending releases, Pocahontas and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. The production at Pixar, hundreds of miles away, was hardly their concern. Not even the obvious choice, toy licenses for the film’s characters such as Woody and Buzz, were getting Disney excited about the material. In February 1995, just a month after the film was announced for release that November, a small toy company called Thinkway Toys took a bid to create toys for the film that would become hugely successful. When the film finally opened on November 22, just in time for the Thanksgiving rush, Burger King, as well as both PepsiCo and Coca-Cola Co. had promotional material driving audiences to see Toy Story, which most audiences and critics alike misunderstood as a Disney film otherwise animated on computers by Pixar. One can only speculate as to the outcome had audiences known that Disney was simply distributing a Pixar production, though likely the Disney name, and the comprehensive ad campaigns, would have drawn a massive audience regardless. As is, the film earned high praise from critics, even if they failed to understand the Disney-Pixar relationship, and went on to make $192 million in domestic box-office receipts and $357 million worldwide.

Partnership with Pixar gave Disney access to computer technology that would help complete the computerized ballroom sequence in Beauty and the Beast, the collapse of the Cave of Wonders in Aladdin, and the stampede in The Lion King. And yet, Disney inadvertently opened themselves up to competition against a staggeringly powerful competitor by proving Pixar, and all computer-animated films, capable of box-office success. Disney’s arms reached further by name alone, as their release schedule and animation history proved more prolific, although, in time, Pixar would overcome the House of Mouse and render their hand-drawn form of animation all but obsolete as the theatrical standard medium for animation. Disney eventually shifted their output to computer animation, releasing Chicken Little and Bolt in the format; however these attempts have failed to match the singularity of a Pixar film.

Pixar’s triumph made way for other computer-animation competitors as well, such as Dreamworks (Madagascar), Fox (Ice Age), and Sony (Surf’s Up), none of which compare to Pixar, who benefitted in unforeseen ways by their association with Disney. In time, Pixar earned a form of autonomy from Disney, despite whatever trials they may have endured on their first feature film outing. In 2004, with the end of Pixar’s original distribution contract with Disney just around the corner, Jobs could have cut Disney loose entirely. Mercifully, he did not. In order to make the most of the partnership from both perspectives, Pixar was purchased in 2006 by Disney Corporation for $7.4 billion, a decision spearheaded by Robert Iger, the CEO who replaced Michael Eisner. Having nearly shut down production on Toy Story, which would have surely ended Pixar altogether, Disney was now clinging to Pixar for dear life. Over the years, Disney had made a vast sum distributing Pixar blockbusters and very little from their own series of increasingly unwatchable animated flops. And so one cannot help but wonder who benefited more from Pixar’s decision to allow Disney to distribute their films. Certainly, the name “Disney” on any poster or marquee does not harm a film’s chances to draw an audience, and yet, does it draw an exclusive audience that the name “Pixar” would not? Perhaps. But the new terms of the Disney-Pixar relationship ultimately empowered Pixar, leaving them with unequivocal creative control. After the deal, high concept, daring pictures like Ratatouille, WALL·E, and even John Carter challenge audiences in ways that proved Pixar was more than “family” films.

Pixar’s distinctive fusion of artistry and universal storytelling has been called everything from “Pixar Magic” to “The Pixar Touch,” the latter a welcomed nod to the effortless delight of Ernst Lubitsch films. And certainly, there exists an indefinable element of joy with each of the animation studio’s releases, which is only enhanced when one considers how they continue to make these astonishing computer-animated films time and again. Toy Story stands as an emblem for Pixar by telling the small guy’s tale, an account of the diminutive toy who, despite his size, remains capable of anything. But this is also the tale about the imagination that a child, or an animator, can bring to a seemingly inert object. Whenever watching the film, an eternally charming account of the world of toys, imagine that the story told is that of Pixar, the little company who proved, both through their own story and their film, the infinite possibility of imagination.

Bibliography:

Auzenne, Valliere Richard. The Visualization Quest: A History of Computer Animation. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

Lasseter, John; Daly, Steve. Toy Story: The Art and Making of the Animated Film. New York: Hyperion, 1995.

Price, David A. The Pixar Touch. New York: Knopf, 2008.

Thomas, Bob. The Art of Animation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review