The Definitives

Touch of Evil (1958)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The maligned directorial history of Orson Welles offers an archetypal cautionary tale and horror story for other filmmakers to reflect upon and ultimately avoid. Welles stands in for every visionary director who has ever battled the monster of the Hollywood System and found themselves defeated. Every entry in Welles’ cinematic career, save for his first motion picture, Citizen Kane, met with production difficulties in some form or another and reached the silver screen in a shape not adhering to his original vision, if at all. Meddling studio executives, budgetary troubles, and creative differences left the filmography of this greatest of auteurs riddled by films taken from him, recut and reformatted, and released in a manner against his wishes. At the same time, he watched, powerless, lamenting the outcome of his labors. As a result, the production histories for his earlier films such as The Magnificent Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai, and Mr. Arkadin contain almost as much pure drama as the screen stories themselves. And yet, each is a masterpiece despite their tampered result. None so much as Welles’ 1958 picture Touch of Evil.

His last directorial effort for Hollywood, Touch of Evil endured the perils of studio intervention yet survived to earn itself, after much time, a release that closely resembled the director’s intentions. Removed from its production after turning over his cut, Welles, then crushed after enduring many such interventions, watched as his film was altered by studio execs. In a letter to London’s New Statesman publication commenting on his brand of filmmaking, Welles wrote, “I must face the likelihood that I shall not again be able to put it to the service of any theme of my own choosing.” His protests notwithstanding, the film became another in a long line of Wellesian catastrophes. Not until 1998, when film scholars reassembled footage for a Restored Version of Touch of Evil, guided by extensive production notes from Welles himself, was there a penultimate version of the director’s film. Sadly, Welles passed away thirteen years prior and never witnessed the final assembly of his trials released on a wide scale.

Welles’ track record of failed film projects began to catch up with him after Touch of Evil. He told Cahiers du Cinéma in June 1958, “I’m seriously considering putting a complete stop to all cinematic or theatrical activity, to end it once and for all, because I’ve had too many disillusions. I’ve devoted too much work, too much effort, for what has been given in return.” Indeed, it was the last straw for Welles, who had suffered much at the hands of producers indifferent to his artistic needs. When production on Touch of Evil began in early 1957, Welles’ stature had metamorphosed from a thin, good-looking actor and professed wunderkind of Hollywood in the early 1940s into an overweight, down-and-out director taking bit acting roles and narration jobs to finance his independent projects, which inevitably fell through. After co-starring in the Western Man in the Shadow for Universal Studios, Welles received a script based on Whit Masterson’s cheap novel Badge of Evil and considered taking a supporting role offered by the studio. Welles admitted, “I was still wondering whether I could afford not to make it when they called up Chuck Heston.” Then accomplished actor Charlton Heston was approached as well and was told, “We have Welles.” Believing this meant Welles would direct—or Heston recommended Welles as the director, depending on whose story you believe, Welles or Heston—Heston agreed to star in the picture, which then forced Universal to offer Welles the director’s chair. Whoever deserves the credit for getting Welles the job, Welles agreed only if he could rewrite the script to his liking. He accepted the offer with the understanding that he would get nothing from the profits of the film. Heston would earn 7.5 percent of receipts. Welles admitted later that he was just happy to take the reins of a Hollywood picture for the first time since The Lady from Shanghai in 1947.

Over three-and-a-half weeks the filmmaker removed almost any semblance of Masterson’s original yarn, except for the tape recorder finale in a very skeletal outline, and kept some hints of the first script by Paul Monash. Most significantly, Welles moved the story’s focus onto his character, the corrupt American police captain Hank Quinlan, to help personify the film’s themes. Further imprinting his signature onto the tale, Welles changed the protagonist and his wife from an American detective with a Mexican wife to a Mexican detective with an American wife—though both roles were inevitably played by American actors. Still, the very concept of an American male with a Mexican woman was hardly unconventional, whereas the opposite challenged the narrative and social standards of the period. Welles also moved the setting to the United States-Mexico border, the fictional town of Los Robles (the original setting was San Diego), to help emphasize this mixed-race relationship between husband and wife, hero and villain. Finally, lacing his entire yarn with undercurrents of race, sex, drugs, rape, and murder, Welles transformed a safe studio thriller into a disturbing, if not perverse horror story about moral decay and shattered ideals. Since Welles’ box office record as a director had not seen profits since 1946’s The Stranger, his changes to the script concerned the studio, but seemed to confirm what Heston had hoped, that Welles would make “an offbeat film out of what they’d planned as a predictable little programmer.”

Over three-and-a-half weeks the filmmaker removed almost any semblance of Masterson’s original yarn, except for the tape recorder finale in a very skeletal outline, and kept some hints of the first script by Paul Monash. Most significantly, Welles moved the story’s focus onto his character, the corrupt American police captain Hank Quinlan, to help personify the film’s themes. Further imprinting his signature onto the tale, Welles changed the protagonist and his wife from an American detective with a Mexican wife to a Mexican detective with an American wife—though both roles were inevitably played by American actors. Still, the very concept of an American male with a Mexican woman was hardly unconventional, whereas the opposite challenged the narrative and social standards of the period. Welles also moved the setting to the United States-Mexico border, the fictional town of Los Robles (the original setting was San Diego), to help emphasize this mixed-race relationship between husband and wife, hero and villain. Finally, lacing his entire yarn with undercurrents of race, sex, drugs, rape, and murder, Welles transformed a safe studio thriller into a disturbing, if not perverse horror story about moral decay and shattered ideals. Since Welles’ box office record as a director had not seen profits since 1946’s The Stranger, his changes to the script concerned the studio, but seemed to confirm what Heston had hoped, that Welles would make “an offbeat film out of what they’d planned as a predictable little programmer.”

Shooting began on February 18, 1957, and continued through April 2. The Mexican government, troubled by the seedy nature of Welles’ setting, refused to allow shooting on their border and forced the production to relocate. They moved to the rotting city of Venice, California, an entire sprawl that already seemed to survive on the decomposing air of Welles’ Los Robles. But the move was a fortuitous one, as the director would discover. Worried executives were invited to the set by Welles on the first day of shooting. Quite systematically, Welles wanted the studio to see him shoot the interrogation scene shot entirely inside an apartment; the sequence flows in and out of three rooms and was scheduled for two days of shooting. Welles planned with cinematographer Russell Metty where the camera would go through most of the morning and afternoon while the actors rehearsed. The studio reps were left wondering when filming would ever commence. Shortly after the cameras began to roll in the early evening, Welles suddenly called a print. Having completed the entire scene in a single, impressively long take, Welles showboated for Universal and demonstrated that he could shoot efficiently, proving once again his reputation as a virtuoso. Welles conceived the entire setup to keep Universal from nosily looking over his shoulder throughout the rest of production. To be sure, until his initial cut of Touch of Evil was submitted to the studio, they left him in complete control. Shooting out of sequence as the daylight favored the given scene, Welles completed the picture quickly but not hastily in just over a month, spent a little more than what his budget allowed, and remained in charge of his technical and narrative elements on-set. The director called on regulars from his previous work and friends to make brief cameos. Among them, Joseph Cotten plays a coroner, Zsa Zsa Gabor owns the local strip club, Mercedes McCambridge is the Mexican gang leader, and Marlene Dietrich embodies the ethereal role of fortune teller Tanya. And though the remarkable camerawork and star-studded backgrounds offer much to the attentive viewer, Welles’ evident need for and mastery over his craft stands out above all else.

Rather than depict reality, Welles concentrates his faculties on conveying breezy intellect and a baroque world. Every scene feels fully composed, arranged, and labored over, yet filled with sumptuous detail. The foul milieu of the border town is Welles’ filmic playground, filled with brothels, dive bars, and clientele almost exclusively comprised of criminals and lost souls. It’s all accented by the natural drabness of Venice. Metty shoots in extensive deep focus and low angles, keeping everything in sight, while Welles fills the frame with movement, activity, and incredible detail. Trash floats through the streets like a tumbleweed in a Western town. Characters speak in racy tongue, with pulpy insults and colorful exchanges of dialogue. Welles’ mise-en-scène is alive.

Rather than depict reality, Welles concentrates his faculties on conveying breezy intellect and a baroque world. Every scene feels fully composed, arranged, and labored over, yet filled with sumptuous detail. The foul milieu of the border town is Welles’ filmic playground, filled with brothels, dive bars, and clientele almost exclusively comprised of criminals and lost souls. It’s all accented by the natural drabness of Venice. Metty shoots in extensive deep focus and low angles, keeping everything in sight, while Welles fills the frame with movement, activity, and incredible detail. Trash floats through the streets like a tumbleweed in a Western town. Characters speak in racy tongue, with pulpy insults and colorful exchanges of dialogue. Welles’ mise-en-scène is alive.

The first image the audience sees is a bomb. Its timer is set for only three-and-a-half minutes, and the apparatus is placed into the trunk of a car. In the opening crane sequence, camera operator John Russell, who would shoot Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, accomplishes an extending tracking shot that follows the ticking car high and low through the bustling sordid streets of Los Robles and then over the border to American soil. The driver, millionaire Rudy Linnekar, moves along slowly while his mistress in the passenger seat complains of ticking in her head. The camera also trails honeymooning narcotics detective Miguel Vargas (Heston) and his new wife Susie (Janet Leigh) as they walk across the border. Finally, they stop for their first kiss on American soil, and—BOOM!—the dynamite explodes the car before their lips ever touch. This windingly smart single shot establishes the murder that sets into motion the plot, the mixed-race marriage of the protagonists, and the personality of Los Robles. It exists as one of the most impressive sequences in all of cinema.

Enter Hank Quinlan, who arrives on the scene only after those who arrive first have time to talk up his reputation to Vargas. Wellesian characters from Harry Lime to Gregory Arkadin have a way of making grand entrances. And while he seldom plays the top-billed character, Welles’ roles are often central. A cigar in his chops and his massive weight leaning on a cane, Welles plays Quinlan without consideration of himself. The audience looks up to Quinlan not because he is admirable; instead, because the camera is positioned underneath him, awed by his hulking, sweaty, bullying demeanor. And though Welles was certainly no physical ideal at the time, he enhanced Quinlan’s crumbling appearance with makeup. He wore padding to increase his size, makeup to make his face blotchy and worn, and fake bags under his eyes. Here, Welles underacts when in his other work, he might be accused of overacting. His appearance does most of the work. Through Quinlan’s dialogue, he mumbles through grunting and throaty, growling like a cranky bear awoken from its slumber. When Quinlan first meets his Mexican counterpart, he points out, “You don’t talk like one.” And Vargas’ wife, “She don’t look like a Mexican either.”

Heston makes a chiseled Latino hero, and his character’s marriage to a white woman, in addition to the conclusion of the story, tampers with Hollywood’s then-current need for a white hero. Typically, the Mexican Vargas would be the villainous cop, whereas the American Quinlan would prove the steadfast lead. Welles flip-flops race roles for the sake of irony and audience confrontation, allowing Welles’ contrast to blossom when his American hero is actually the enemy, and his Mexican enemy is actually the hero. Furthermore, Welles depicts Quinlan as a racist incapable of respecting Vargas no matter how renowned his standing. Though their accomplishments are equal, Quinlan still grumbles, “I don’t want to leave that Vargas guy alone.” Along with other comments such as “I don’t speak Mexican,” Quinlan’s discrimination contributes to his eventual demise. Welles broke down borders with these themes and presented a Mexican hero who bests an American.

Although the bomb was planted on Mexican soil, Vargas avoids all jurisdictional debates with Quinlan by requesting to be an observer in the investigation. As her husband goes to work, Susie returns to their hotel and receives a passive threat from Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff), brother to the Mexican drug lord recently captured by Vargas. Along with the Grandi boys, they lick their lips at the blonde beauty and send her back with a warning for her husband to stand down. Quinlan is unsurprised when he hears this, and he insults Vargas’ wife, claiming she was “picked up” by the Grandi boys. Quinlan has a murderer to catch and cannot be bothered with the affairs of a Mexican like Vargas. Followed by his longtime partner Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia), Quinlan trails a petty clue to the young Mexican Sanchez (Victor Millan), whose fling with Linnekar’s daughter becomes apparent when they arrive. Perhaps Sanchez murdered Linnekar to get at his money—Quinlan’s bad leg, which twitches with intuition, tells him so. After some harsh strong-arming interrogation tactics, Menzies finds a shoebox containing two sticks of dynamite in Sanchez’s bathroom. The only problem is, Vargas was in that bathroom earlier and knocked over what was then an empty shoebox. So Quinlan must have framed Sanchez and planted evidence to get his collar.

Although the bomb was planted on Mexican soil, Vargas avoids all jurisdictional debates with Quinlan by requesting to be an observer in the investigation. As her husband goes to work, Susie returns to their hotel and receives a passive threat from Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff), brother to the Mexican drug lord recently captured by Vargas. Along with the Grandi boys, they lick their lips at the blonde beauty and send her back with a warning for her husband to stand down. Quinlan is unsurprised when he hears this, and he insults Vargas’ wife, claiming she was “picked up” by the Grandi boys. Quinlan has a murderer to catch and cannot be bothered with the affairs of a Mexican like Vargas. Followed by his longtime partner Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia), Quinlan trails a petty clue to the young Mexican Sanchez (Victor Millan), whose fling with Linnekar’s daughter becomes apparent when they arrive. Perhaps Sanchez murdered Linnekar to get at his money—Quinlan’s bad leg, which twitches with intuition, tells him so. After some harsh strong-arming interrogation tactics, Menzies finds a shoebox containing two sticks of dynamite in Sanchez’s bathroom. The only problem is, Vargas was in that bathroom earlier and knocked over what was then an empty shoebox. So Quinlan must have framed Sanchez and planted evidence to get his collar.

Running on that lead, Vargas voices that he plans to investigate Quinlan for the frame job. Desperate, Quinlan allows Uncle Joe Grandi to convince him that they have a common goal of taking down Vargas. Meanwhile, Vargas leaves Susie on the American side for her protection—in a secluded motel that the Grandi family owns unbeknownst to her husband. There, she is drugged, raped, and then kidnapped by the Grandi gang. Stripped down and tied to a bedpost, Quinlan frames her for the murder of Uncle Joe Grandi, whom he strangles in an attempt to cover up his corruption. Vargas tries to convince Menzies that his friend and partner Quinlan is a crooked cop. Menzies was saved by Quinlan long ago and now has a case of hero-worship. Not until Menzies finds Quinlan’s cane in Susie’s hotel room with the strangled body of Grandi does he believe his partner is guilty. Quinlan, having not slept since before the car bomb, resorts to alcohol. He finds himself wandering into the dive owned by his old gypsy friend Tanya. After Welles thought up the character well into production, Marlene Dietrich received a call to play the role. He asked her to “be dark” and simulate her appearance in Golden Earrings of 1947. She appeared in her few scenes as Tanya uncredited and unpaid, until Universal execs saw her in rushes and ensured she was paid. Dietrich’s performance haunts the film and offers the audience some doubt that Quinlan has always been a villain. At first, Tanya does not see Quinlan; he has to reintroduce himself, at which point she remarks on his wasted-away appearance: “I didn’t recognize you. You should lay off those candy bars.” Later she observes, “You’re a mess, honey.” Welles must have been aware of the self-debasing commentary, given the state of his career. And bearing in mind his future career as a filmmaker, or lack thereof, Tanya’s final words to Quinlan resonate even further when he asks Tanya to read his fortune: “You haven’t got any. Your future’s all used up.”

The finale is more about Quinlan and Menzies than Vargas’ justice or Susie’s absolution. Quinlan took a bullet in the leg long ago to save his friend Menzies, and that gesture, along with his prolific career, has made him an idol. Now even his past heroics cannot overshadow his current crimes, as the loss of his cane indicates. Representing Menzies and the noble sacrifice Quinlan made for his partner, the cane can no longer support the warped Captain. So his nobility is gone. Without it, Quinlan falls into a sewer of moral ruin and frees Menzies of his admiration. Coaxing Quinlan out of Tanya’s place, Menzies draws out a confession while Vargas follows and records their conversation on a wire. Echoes ring out from Vargas’ recorder as his subjects pass over a bridge with him under it. Seeing through the rouse, Quinlan shoots Menzies, calls for Vargas to come out, and takes aim. Menzies stops him with a bullet. “That’s the second bullet I stopped for you,” Quinlan muses, realizing the scope of his transgressions just before falling to his death. Though Vargas represents the protagonist in the film, the ornate undertonal themes of infected morality apply to Hank Quinlan and encompass the central narrative arc. François Truffaut commented that Welles makes “the monster more and more monstrous, and the young protagonist more and more likable, until we are brought somehow to shed real tears over the corpse of the magnificent monster.” Quinlan sees himself as an instrument of justice, and that he has become a murderer is simply the next logical step in dispensing that justice. When he realizes this, of course, it becomes his self-defeating flaw. Quinlan admits, “What I’ve got is a nose for guilt,” and by the end, perhaps he sniffs himself out.

The finale is more about Quinlan and Menzies than Vargas’ justice or Susie’s absolution. Quinlan took a bullet in the leg long ago to save his friend Menzies, and that gesture, along with his prolific career, has made him an idol. Now even his past heroics cannot overshadow his current crimes, as the loss of his cane indicates. Representing Menzies and the noble sacrifice Quinlan made for his partner, the cane can no longer support the warped Captain. So his nobility is gone. Without it, Quinlan falls into a sewer of moral ruin and frees Menzies of his admiration. Coaxing Quinlan out of Tanya’s place, Menzies draws out a confession while Vargas follows and records their conversation on a wire. Echoes ring out from Vargas’ recorder as his subjects pass over a bridge with him under it. Seeing through the rouse, Quinlan shoots Menzies, calls for Vargas to come out, and takes aim. Menzies stops him with a bullet. “That’s the second bullet I stopped for you,” Quinlan muses, realizing the scope of his transgressions just before falling to his death. Though Vargas represents the protagonist in the film, the ornate undertonal themes of infected morality apply to Hank Quinlan and encompass the central narrative arc. François Truffaut commented that Welles makes “the monster more and more monstrous, and the young protagonist more and more likable, until we are brought somehow to shed real tears over the corpse of the magnificent monster.” Quinlan sees himself as an instrument of justice, and that he has become a murderer is simply the next logical step in dispensing that justice. When he realizes this, of course, it becomes his self-defeating flaw. Quinlan admits, “What I’ve got is a nose for guilt,” and by the end, perhaps he sniffs himself out.

In his famous interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Welles insists that Touch of Evil is not an exercise in autobiography. Instead, his melodramatic aim was a conflict between skewed variations of good and evil. Quinlan is a hopeless character that cannot be saved, but he is the personification of evil. As Welles himself points out, “I have to like him because he loved Marlene Dietrich and saved his friend from a bullet. But what he stands for is detestable.” Perhaps then, the film’s message is that good is absolute, while evil grows through increasing degrees, like a tumor. Themes of innocence lost distort the purity of the opposing sides, as Quinlan has, over time, betrayed the law and himself, making the character worthy of tragic pity. The air of tragedy around Quinlan grows even more powerful when it’s revealed that Sanchez did plant the bomb and that Quinlan’s intuition was right after all. Tanya argues in the end, “What does it matter what you say about people?” But why not consider Quinlan an illustration of Welles himself, trying desperately to gain control over his production while everything around him falls apart, just as Quinlan loses grip on the reins of his murderous scheme? Both men contain equal parts of self-loathing and self-admiration, feelings that are self-referential in the film, and at odds with each other on and off the screen. Eventually, Quinlan’s case becomes Vargas’, just as Welles’ production became the studios’, and both men are left dead in the water. But how could Welles predict that the fate of his last Hollywood film would correspond to the doom of his character? After all, it was not until after the majority of post-production had been completed that Universal took the film away from him. Perhaps Quinlan and Welles’ similar outcomes are a coincidence dwelled upon too much by his biographers, though the comparison is fascinating, even eerie upon examination.

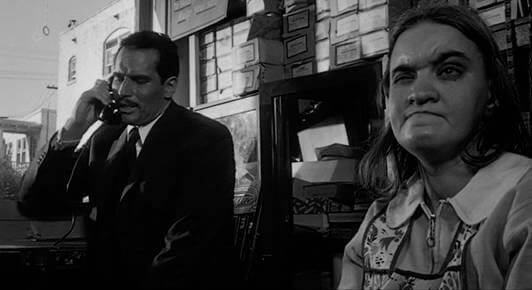

The macabre and morbid potency of Touch of Evil sealed the film’s fate and that of Welles in Hollywood, as studio heads could not find a narrative reason behind his tone, except to say that Welles was needlessly trying to be provocative. Since their director was the man behind Citizen Kane, an affront attack on the media’s most powerful mogul, why should his approach be a surprise? In subsequent years, Welles defended himself in many writings and interviews, suggesting the film’s degenerate climate was meant to mirror Quinlan. After all, the pollution of one’s character is a slow, grueling process that Welles understood was not without grave and horrible influences. The studio scoffed at the scene where Quinlan strangles Grandi because the victim’s eyes bulge out of his head, which Welles admits went too far, but it also evokes an appropriate sense of terror. And the studio was so offended by the presence of a blind woman in the foreground while Vargas makes a telephone call that in some versions of Touch of Evil, the frame is zoomed onto Vargas to eliminate her from the shot. Welles confessed that he intended the blind woman’s presence to elicit feelings of discomfort but also to reflect Los Robles, a place where only the blind can see, and a hobbling police Captain is king. If the film’s temperament takes a cue from Quinlan, Welles’ stark manifestation of the depths of perversity is not only fitting but worthy of celebration for their audacity.

The macabre and morbid potency of Touch of Evil sealed the film’s fate and that of Welles in Hollywood, as studio heads could not find a narrative reason behind his tone, except to say that Welles was needlessly trying to be provocative. Since their director was the man behind Citizen Kane, an affront attack on the media’s most powerful mogul, why should his approach be a surprise? In subsequent years, Welles defended himself in many writings and interviews, suggesting the film’s degenerate climate was meant to mirror Quinlan. After all, the pollution of one’s character is a slow, grueling process that Welles understood was not without grave and horrible influences. The studio scoffed at the scene where Quinlan strangles Grandi because the victim’s eyes bulge out of his head, which Welles admits went too far, but it also evokes an appropriate sense of terror. And the studio was so offended by the presence of a blind woman in the foreground while Vargas makes a telephone call that in some versions of Touch of Evil, the frame is zoomed onto Vargas to eliminate her from the shot. Welles confessed that he intended the blind woman’s presence to elicit feelings of discomfort but also to reflect Los Robles, a place where only the blind can see, and a hobbling police Captain is king. If the film’s temperament takes a cue from Quinlan, Welles’ stark manifestation of the depths of perversity is not only fitting but worthy of celebration for their audacity.

And yet, the studio curiously ignored the gang-rape sequence at the Mirador hotel, punctuated by Henry Mancini’s dizzying bongo-laden jazz-rock score, whose sonic subtext alone was already feral with sexual tempo. This scene creates an incomparably unsettling moment in mainstream cinema. Susie waits for her husband to return from his investigation. Sprawled out on the bed in her lingerie, she knows not what awaits her. The trembling, agonizingly spooky voice of the motel’s sexually repressed night watchman (Dennis Weaver) nervously characterizes how the film dances around the topic of gang rape, depicting it without ever showing or discussing it outright. The watchman’s unsettling nature undoubtedly inspired Anthony Perkins’ performance as a likewise repressed motel clerk in Hitchcock’s Psycho two years later, just as the Mirador, a small motel now almost deserted because the main highway was diverted, inspired the Bates Motel. And strangely enough, Janet Leigh plays the victim in both films. The horrible details of the rape are not shown, of course, but enough evidence remains in the disturbing chatter delivered in whispers through walls. Susie hears bustling all around her, a silent tension. She realizes the phone is dead, and then from the next room, a woman’s voice warns, “You know what the boys are trying to do, don’t you?” Shot in an actual motel room, filming the scene bore a terrifying reality that frightened Leigh. The gang enters the room laughing, encircling the bed where Susie lay frozen still with fear. The female leader (McCambridge), darkened with shoe polish to represent the Mexican Other, says, “Lemmie stay, I want to watch.” One of the boys hisses, “Hold her legs.” A shadow casts over Susie’s face. From outside, we see the hotel room door slam shut. That the censor board left this scene in—believing it to be, perhaps, just a forced drugging as the plot later suggests—confirms Welles was ambiguous enough to fool them. But there is no mistake about what happens, as Welles would later confirm.

Post-production lasted until November, when a rough cut was handed over and viewed by studio chiefs. Welles moved on, believing his work finished, but the studio wanted alterations made; since their director was not available, they quickly found other talent to fill the gap. The studio informed Heston that Welles would no longer continue working on the film and that any extra filming, editing, or dubbing would be supervised by replacement director Harry Keller. Though Welles appealed to his star for help when he heard of this news, Heston, then eyeing the presidency of the Actor’s Guild, was not about to stand up to his employers. Welles was clued to the severity of their decision when his car was stopped at the gate to Universal Studios and found the guard was under strict orders not to let the filmmaker enter. He later attributed the studio’s reaction to the picture being “just too dark and black and strange for them.” Released as a B-movie on the bottom of a double bill with almost no press exposure, the studio buried the film despite it earning high praise in France. The “General Release” version distributed by Universal places the film titles over Welles’ opening bomb tracking shot, a sequence which they cut into several pieces, though the director intended explicitly for all credits to appear at the end. Whole characters are edited away, the broad sense of strangeness is softened, and the active tempo of the entire production waned. These changes erased Welles’ signature and disrupted his “most precise pattern involving rather special arrangements of sound and silence.” Universal’s conquest of the picture spawned the now-legendary 58-page memo written by Welles to protest the changes made. Some forty years later in 1998, the memo served as the basis for a re-edit and re-release, though the picture is still not as complete as it should be. When producer Rick Schmidlin read critic Jonathan Rosenbaum’s article in a 1992 edition of Film Quarterly, which details large portions of Welles’ memo, he set out to reconstruct Welles’ vision. Coming too late in the game, Schmidlin’s work could never be complete, as some of the materials that might realize Welles’ film as the director intended were long since disposed of by the studio.

Post-production lasted until November, when a rough cut was handed over and viewed by studio chiefs. Welles moved on, believing his work finished, but the studio wanted alterations made; since their director was not available, they quickly found other talent to fill the gap. The studio informed Heston that Welles would no longer continue working on the film and that any extra filming, editing, or dubbing would be supervised by replacement director Harry Keller. Though Welles appealed to his star for help when he heard of this news, Heston, then eyeing the presidency of the Actor’s Guild, was not about to stand up to his employers. Welles was clued to the severity of their decision when his car was stopped at the gate to Universal Studios and found the guard was under strict orders not to let the filmmaker enter. He later attributed the studio’s reaction to the picture being “just too dark and black and strange for them.” Released as a B-movie on the bottom of a double bill with almost no press exposure, the studio buried the film despite it earning high praise in France. The “General Release” version distributed by Universal places the film titles over Welles’ opening bomb tracking shot, a sequence which they cut into several pieces, though the director intended explicitly for all credits to appear at the end. Whole characters are edited away, the broad sense of strangeness is softened, and the active tempo of the entire production waned. These changes erased Welles’ signature and disrupted his “most precise pattern involving rather special arrangements of sound and silence.” Universal’s conquest of the picture spawned the now-legendary 58-page memo written by Welles to protest the changes made. Some forty years later in 1998, the memo served as the basis for a re-edit and re-release, though the picture is still not as complete as it should be. When producer Rick Schmidlin read critic Jonathan Rosenbaum’s article in a 1992 edition of Film Quarterly, which details large portions of Welles’ memo, he set out to reconstruct Welles’ vision. Coming too late in the game, Schmidlin’s work could never be complete, as some of the materials that might realize Welles’ film as the director intended were long since disposed of by the studio.

But like all Welles’ films after Citizen Kane, the sole picture that was not taken from its director after production and summarily gang-raped in the editing room, Touch of Evil remains a masterpiece in its repaired state. Six cuts, originating from Universal editors to scholars to Schmidlin, are outlined in impressive detail by Welles’ most defensive biographer Clinton Heylin. And though perhaps not the singular creation of its masterful director, the 1998 version is as close to Welles’ vision as the film is ever likely to be. Tales of production woe would follow Welles until his death in 1985. Before Touch of Evil ever began production, Welles had been slowly completing work on his version of Don Quixote in Spain, another directorial venture that reflects the filmmaker’s unrealistic idealism toward filmmaking. And after the Touch of Evil debacle, he returned to his Quixotic cause, though he would never complete his adaptation. His virtual banishment as a Hollywood director aside, Welles completed an independent production of Franz Kafka’s The Trial in 1962, starring Anthony Perkins; while filming, he met Oja Kodar, his lover and partner for his remaining years. In addition, he completed minor works such as an appreciation of Shakespeare’s reoccurring character Falstaff called Chimes at Midnight in 1966 and an adaptation of Karen Blixen’s The Immortal Story the same year. Welles and Kodar also co-wrote the documentary F for Fake, an exercise in editing film and reality alike. Released in 1974, F for Fake earned the same fate as much of his work in this period—rejection in the United States and praise in Europe. Interspersed between these rarely completed projects were several half-filmed productions that went under for one reason or another; Welles continued to take sometimes embarrassing acting roles in both film and television taken to finance them. The once preeminent rising star of Hollywood, who arrived with such promise on Citizen Kane, would fade out with a whimper.

Welles’ career and his roster of pivotal motion pictures would not be appreciated until long after his prime, with a diminished reputation and ego incapacitated after so many blows. His films’ then-contemporary critics often failed to see their formal and narrative ingenuity, and so not until later historians looked back, out from under the context of troubled productions, could they be viewed as whole, individual works far ahead of their time, however tainted they may be by studio or financier hands. Indeed, upon its release, critics believed that Touch of Evil contained impressive individual scenes but little substance. But the significance lies outside of social commentary, where Welles connects his environment to his characters. This relationship resonates throughout the picture and grows upon repeated viewings focused on the many flourishing details. That critics and Universal Studios failed to instantly recognize this speaks to Orson Welles’ gift, as with every picture, he presents a multilayered, multitextual construct before the viewer. He steps outside boundaries to create something at once familiar but wholly new that demands reexamination. Unconventional without resorting to outright post-modernism, Touch of Evil reinvents within established parameters and thrills in doing so. Welles employs an engaging, elaborate plot about corruption and saturates his entire picture in exceptionally polluted energy, relying on its noirish mood, bravado camerawork, sharp dialogue, and iconic performances throughout to give the film its tangible atmosphere. As his scenario and the atmosphere converge into their beautifully twisted harmony, he engulfs us in an unremittingly involved cinematic experience that leaves a wonderful stain, rendering it unforgettable. How regrettable, yet appropriately poetic, that this degree of cinematic daring could not be achieved without its author’s passionate struggle and hardship.

Welles’ career and his roster of pivotal motion pictures would not be appreciated until long after his prime, with a diminished reputation and ego incapacitated after so many blows. His films’ then-contemporary critics often failed to see their formal and narrative ingenuity, and so not until later historians looked back, out from under the context of troubled productions, could they be viewed as whole, individual works far ahead of their time, however tainted they may be by studio or financier hands. Indeed, upon its release, critics believed that Touch of Evil contained impressive individual scenes but little substance. But the significance lies outside of social commentary, where Welles connects his environment to his characters. This relationship resonates throughout the picture and grows upon repeated viewings focused on the many flourishing details. That critics and Universal Studios failed to instantly recognize this speaks to Orson Welles’ gift, as with every picture, he presents a multilayered, multitextual construct before the viewer. He steps outside boundaries to create something at once familiar but wholly new that demands reexamination. Unconventional without resorting to outright post-modernism, Touch of Evil reinvents within established parameters and thrills in doing so. Welles employs an engaging, elaborate plot about corruption and saturates his entire picture in exceptionally polluted energy, relying on its noirish mood, bravado camerawork, sharp dialogue, and iconic performances throughout to give the film its tangible atmosphere. As his scenario and the atmosphere converge into their beautifully twisted harmony, he engulfs us in an unremittingly involved cinematic experience that leaves a wonderful stain, rendering it unforgettable. How regrettable, yet appropriately poetic, that this degree of cinematic daring could not be achieved without its author’s passionate struggle and hardship.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André. Orson Welles: a critical view. Foreword by François Truffaut; profile by Jean Cocteau; translated from the French by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Harper & Row, 1978.

Benamou, Catherine L. It’s all true: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey. University of California Press, 2007.

Denning, Michael. The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso, 1998.

Gilmore, James N., Sidney Gottlieb (editors). Orson Welles in Focus: Texts and Contexts. Indiana University Press, 2018.

Heylin, Clinton. Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios. Chicago Review Press, 2005.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. Da Capo Press, 1996.

Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter. This is Orson Welles. Edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Da Capo Press, 1998.

Wilson, Kristi M., and Tomás F. Crowder-Taraborrelli (editors). Film and Genocide. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review