The Definitives

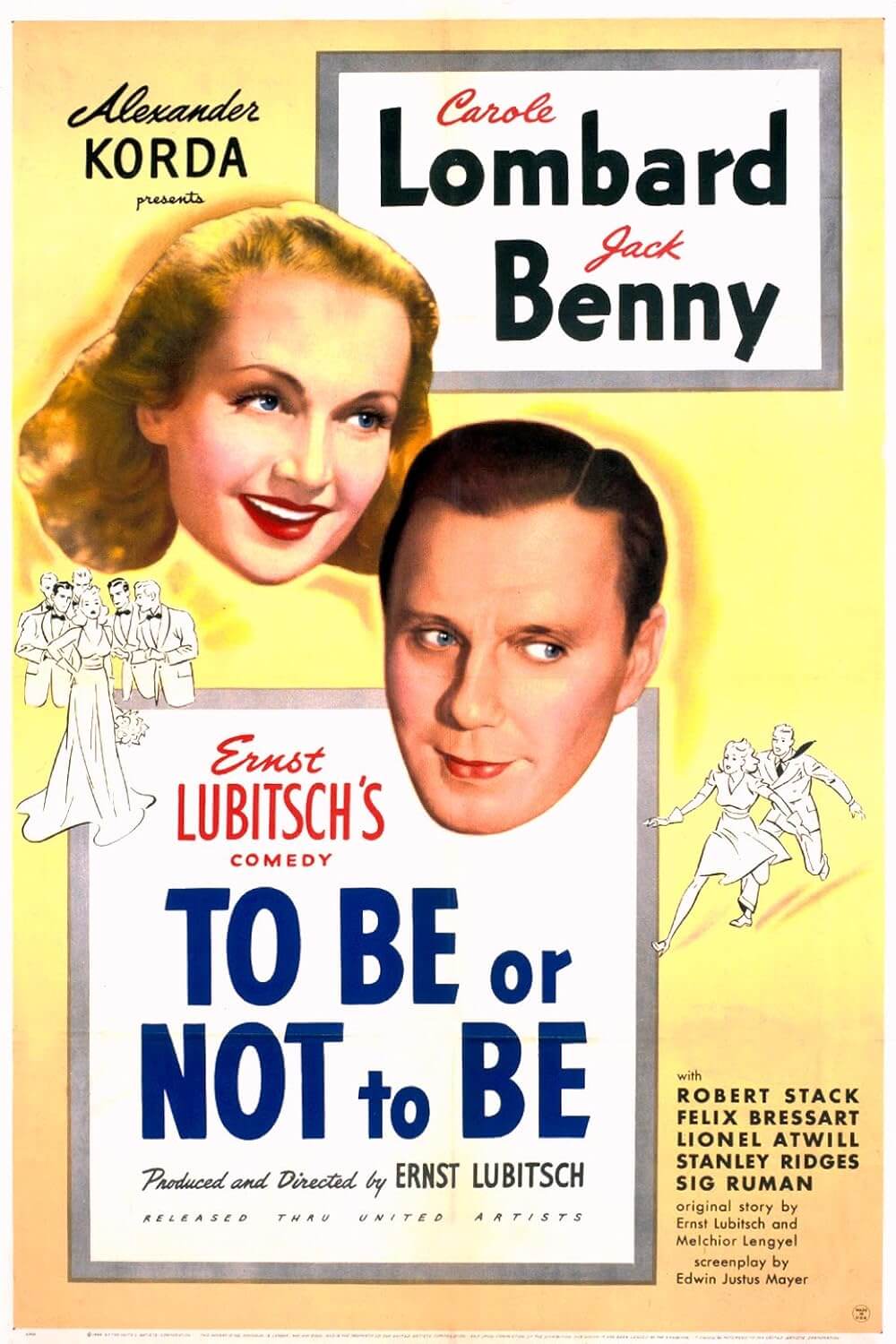

To Be or Not to Be (1942)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

To set the stage, in the last months of 1941, the world’s political climate was unfathomably grim. Hitler’s forces invaded Moscow in October of that year, and the battle continued until the following January when Stalin’s counteroffensive drove back the assault. Hundreds of thousands died in the fight. On November 13, the torpedoing of Britain’s long-serving HMS Ark Royal by a German submarine led to an investigation of its Captain’s negligence for letting the ship sink. America was effectively brought into World War II when the Imperial Japanese Navy surprise attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, killing thousands. In January of 1942, Hitler’s “man with the iron heart” Reinhard Heydrich spoke at the Wannsee Conference and detailed plans for the Third Reich’s final solution to the Jewish Question; upward of six million Jews lost their lives after they were deported to camps like Auschwitz in Poland. Fascism had spread throughout Europe, and Allied forces had not yet organized to elicit much hope of stopping them. Nevertheless, it was during this time of foreboding that Berlin-born Jewish filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch decided to make a comedy about a troupe of mostly Jewish actors in occupied Warsaw, who masquerade as the Gestapo to protect the Polish Underground.

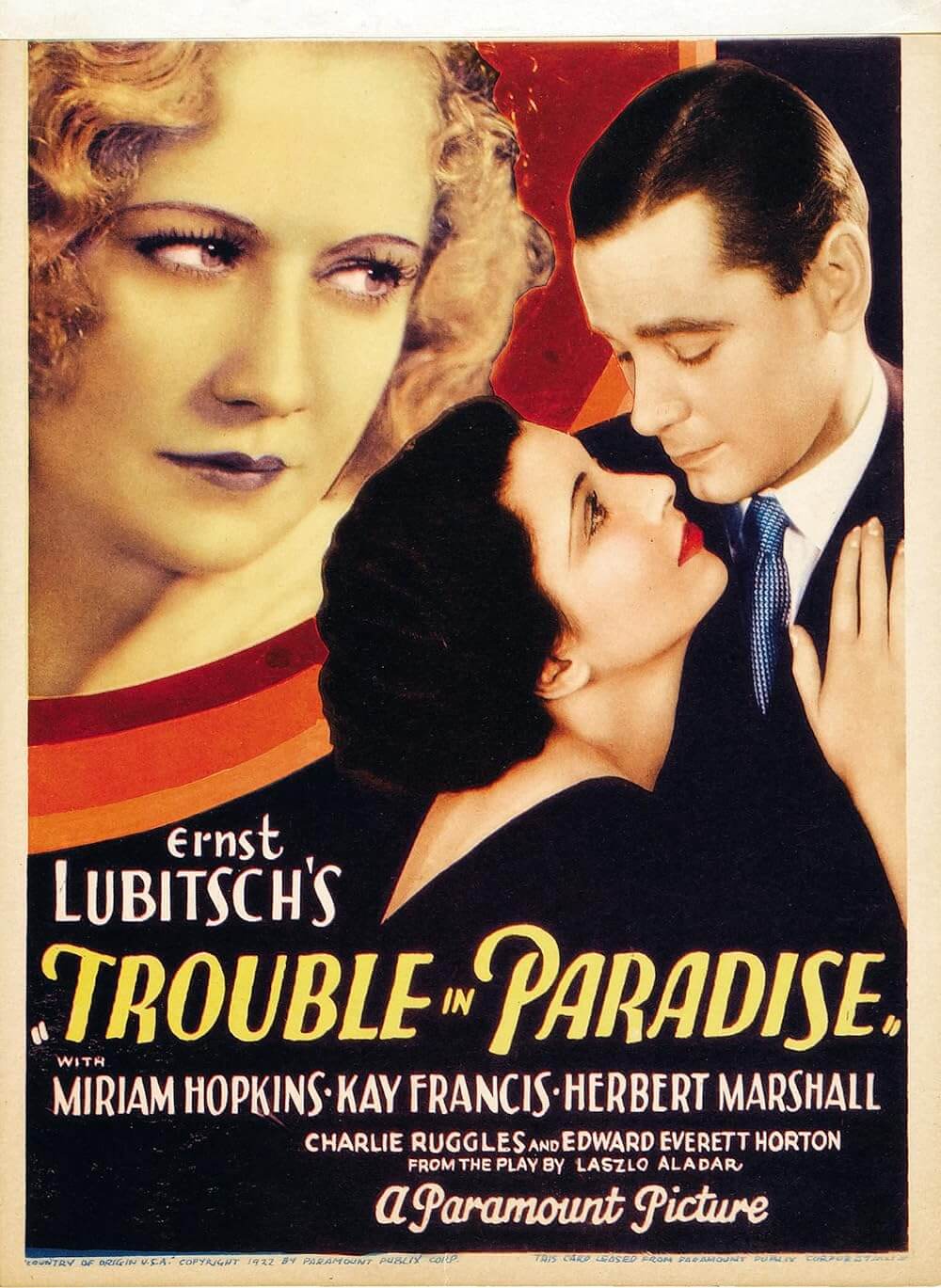

Imagine if a comedy about al-Qaeda terrorists attacking the World Trade Center had gone into production in the summer of 2001 and been released shortly after 9/11. That would be the modern-day equivalent of Lubitsch shooting To Be or Not to Be in Hollywood in late 1941 for a premiere of March 6, 1942. When it was released, many believed the film broached its subject far too soon to be deemed in good taste; Lubitsch was accused of treating taboo material as though it was primed for a farce, complete with slapstick and witticisms about the savagery of Nazis. After all, it looked as though Hitler might actually win at that point in history, and therefore it was no laughing matter. And yet, as Jewish artists, Lubitsch and scriptwriter Edwin Justus Mayer knew their subject all too well, enough to suggest that they did not raise this unthinkable subject naively or without reflection. If there’s one thing Lubitsch took seriously, it’s comedy. In his many attributed romantic comedies, such as Trouble in Paradise (1932) or Design for Living (1933), he used comedy to emphasize the truth about relationships, infidelity, and sex. In To Be or Not to Be, he emphasizes a profound truth indeed—that Nazis were not the superhuman monsters that so many cinematic representations made them out to be. Rather, they were preposterously cruel and deluded human beings, and whoever chose to follow ridiculous figures such as Hitler were equally incompetent. Lubitsch also demonstrated how vulnerable the Nazis could be, an important message to incite U.S. involvement in World War II.

Nothing is what it seems in the film, which opens in 1939 as Hitler appears in Warsaw all alone, walking down the street, much to the shock of Polish onlookers. You see, this is actually Bronski (Tom Dugan), a Polish actor determined to prove his Hitler costume and false mustache look authentic. On the stage at the nearby Polski Theater, rehearsals are underway for a new anti-Nazi play, a farce depicting Nazis as the sorts who buy a child’s loyalty by supplying him with a toy tank. The play’s director argues the performances are too broad and unbelievable, and that Bronki looks unconvincing as Hitler. “To me, he’s just a man with a little mustache,” the director explains. The crew responds, “But so is Hitler!” Production halts when an official bans their play in fear of upsetting Germany. Instead, the company replaces their anti-Nazi play with Hamlet, starring “that great, great Polish actor” Joseph Tura (Jack Benny) and his elegant wife Maria (Carole Lombard), both local celebrities. Taken by the affections of a young pilot, Lieutenant Sobinski (Robert Stack), Maria asks her admirer to meet her backstage during her husband’s performance of Hamlet’s soliloquy. Once “To be or not to be” begins, Sobinski shuffles out to visit Maria in her dressing room, while onstage, Joseph, none the wiser to his wife’s rendezvous, believes the pilot has left because of his performance.

Nothing is what it seems in the film, which opens in 1939 as Hitler appears in Warsaw all alone, walking down the street, much to the shock of Polish onlookers. You see, this is actually Bronski (Tom Dugan), a Polish actor determined to prove his Hitler costume and false mustache look authentic. On the stage at the nearby Polski Theater, rehearsals are underway for a new anti-Nazi play, a farce depicting Nazis as the sorts who buy a child’s loyalty by supplying him with a toy tank. The play’s director argues the performances are too broad and unbelievable, and that Bronki looks unconvincing as Hitler. “To me, he’s just a man with a little mustache,” the director explains. The crew responds, “But so is Hitler!” Production halts when an official bans their play in fear of upsetting Germany. Instead, the company replaces their anti-Nazi play with Hamlet, starring “that great, great Polish actor” Joseph Tura (Jack Benny) and his elegant wife Maria (Carole Lombard), both local celebrities. Taken by the affections of a young pilot, Lieutenant Sobinski (Robert Stack), Maria asks her admirer to meet her backstage during her husband’s performance of Hamlet’s soliloquy. Once “To be or not to be” begins, Sobinski shuffles out to visit Maria in her dressing room, while onstage, Joseph, none the wiser to his wife’s rendezvous, believes the pilot has left because of his performance.

Before long, the Nazis crossed over Polish borders without even declaring war. Joseph’s jealousy over his wife’s admirer reaches its peak, and Sobinski leaves to connect with the Polish Squadron of the Royal Air Force (RAF). While on base, Sobinski meets Professor Siletsky (Stanley Ridges), who claims to be a member of the Polish resistance. Talking to some of the Polish pilots, the Professor gathers lists of the pilots’ families in hiding with the Underground and promises to make sure they’re safe, except Sobinski suspects the Professor is a spy when he says he’s never heard of the famous Maria Tura. What good Pole hasn’t? But by the time Sobinski reports his suspicions to his superiors, the Professor has already left for Warsaw with the report of Polish names and locations for his connections in the Gestapo. If they get in the Gestapo’s hands, the Polish families in hiding are dead. Sobinski follows and contacts the Underground with Maria’s help, and together they devise a scheme to get the report away from the Professor. Maria agrees to seduce the Professor at his hotel room inside a Nazi fortress, but before she can, he’s called away to Gestapo Headquarters to meet the dreaded Col. Ehrhardt. However, the Professor is intercepted and directed to the Polski Theater, which has been made up to look like Gestapo headquarters. There, Joseph, begrudgingly helping his wife’s admirer Sobinski, impersonates Ehrhardt and spreads his performance too thin. The Professor sees through the charade and tries to escape, but he’s killed onstage by Sobinski.

Trapped at the hotel, Maria is rescued by her husband, who now dons a false beard and glasses to appear as the Professor. Maria destroys the report on the Polish Underground, but Joseph-as-Professor Siletsky is asked to meet the real Col. Ehrhardt (Sig Ruman) at Gestapo Headquarters. Their meeting goes well until the corpse of the real Professor is found. Ehrhardt and his ever-blamed Capt. Schultz (Henry Victor) decide to make the suspected fake Professor, Joseph, sweat a little and leave him in a room with the real Professor’s dead body. Joseph thinks fast and shaves the dead Professor’s beard, and then applies a spare false one. His own ruse would have been a success too, except his troupe, having heard the Gestapo found the real Professor’s body, comes to the rescue disguised as Gestapo officers and drags Joseph away much to the bafflement of Ehrhardt, who has just been convinced that Joseph’s Professor was the real one. At risk if ever Ehrhardt puts their scheme together, the troupe must escape the theater, which is set to receive a welcoming party for Hitler himself. They work out another complex plot where they all dress as Gestapo officers. Bronski is among them, again dressed up as Hitler, minus the mustache; no one notices Bronski is Hitler until he puts on the little cube of hair under his nose. Greenberg (Felix Bressart), one of the troupe who had long wanted to play Shylock, creates a distraction by performing Shylock’s “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech from The Merchant of Venice while facing a band of Nazi soldiers.

Trapped at the hotel, Maria is rescued by her husband, who now dons a false beard and glasses to appear as the Professor. Maria destroys the report on the Polish Underground, but Joseph-as-Professor Siletsky is asked to meet the real Col. Ehrhardt (Sig Ruman) at Gestapo Headquarters. Their meeting goes well until the corpse of the real Professor is found. Ehrhardt and his ever-blamed Capt. Schultz (Henry Victor) decide to make the suspected fake Professor, Joseph, sweat a little and leave him in a room with the real Professor’s dead body. Joseph thinks fast and shaves the dead Professor’s beard, and then applies a spare false one. His own ruse would have been a success too, except his troupe, having heard the Gestapo found the real Professor’s body, comes to the rescue disguised as Gestapo officers and drags Joseph away much to the bafflement of Ehrhardt, who has just been convinced that Joseph’s Professor was the real one. At risk if ever Ehrhardt puts their scheme together, the troupe must escape the theater, which is set to receive a welcoming party for Hitler himself. They work out another complex plot where they all dress as Gestapo officers. Bronski is among them, again dressed up as Hitler, minus the mustache; no one notices Bronski is Hitler until he puts on the little cube of hair under his nose. Greenberg (Felix Bressart), one of the troupe who had long wanted to play Shylock, creates a distraction by performing Shylock’s “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech from The Merchant of Venice while facing a band of Nazi soldiers.

Pretending to cart Greenberg off, the troupe, dressed as Gestapo, escapes the Nazi celebration and stops to gather Maria at her apartment. Ehrhardt has arrived just before them and, with the Professor gone, takes it upon himself to recruit Maria as a Nazi spy in a sloppy seduction. Just then, Bronski, still in his Hitler getup, breaks in on Ehrhardt attempting to entice an unwilling Maria. Ehrhardt believes he has insulted his Führer’s honor and decides to take his own life. Lubitsch shows us only the door to Maria’s room. We hear a gunshot, a pause, and then Ehrhardt shouts “Schultz!”—which the Colonel has done throughout the film whenever he makes a mistake. Meanwhile, the troupe hops a plane to England and escapes as heroes. Resuming acting duties, they make a splash on the London stage, playing Hamlet once more. During Joseph’s performance of Hamlet’s soliloquy, he keeps an eye on Sobinski this time, and the young pilot remains in his seat. A row back, however, another young gentleman gets up when he hears “To be or not to be” and, no doubt, makes his way to Maria’s dressing room.

Note how this complete plot description reads more like an involved spy-thriller than a comedy. One can even see how modern filmmakers might have been inspired by the film: Quentin Tarantino when he made Inglourious Basterds or Paul Verhoeven when he made Black Book. The plot involves disguises, a Mata Hari, elaborate trickery, great danger in the risk of exposure, and several deaths. For To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch, writing in The New York Times just after the film’s release, said he wanted to avoid the two comedic formulas: “Drama with comedy relief and comedy with dramatic relief. I had made up my mind to make a picture with no attempt to relieve anybody from anything at any time.” This is evident in his technical approach, as well. Lubitsch’s usually airy style is similarly blended with other styles to meet the film’s unique demands. When Lubitsch first follows Sobinski into the RAF, the almost documentary training sequence that follows looks like a montage from a war movie. During the Professor’s escape and death sequence, he runs frantically into the Polski Theater, crawling between seats as the spotlight searches like it might during a prison break, or more aptly, a concentration camp. As his pursuers close in, he dashes for the stage and freezes when the spotlight catches him, like some pitch-perfect shot out of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller. When he’s finally shot dead, it happens behind the curtain, which then rises on his poetic collapse. These sequences and plot elements are far too brave, sophisticatedly filmed, and intricately conceived to waive the film off as a comic trifle.

Note how this complete plot description reads more like an involved spy-thriller than a comedy. One can even see how modern filmmakers might have been inspired by the film: Quentin Tarantino when he made Inglourious Basterds or Paul Verhoeven when he made Black Book. The plot involves disguises, a Mata Hari, elaborate trickery, great danger in the risk of exposure, and several deaths. For To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch, writing in The New York Times just after the film’s release, said he wanted to avoid the two comedic formulas: “Drama with comedy relief and comedy with dramatic relief. I had made up my mind to make a picture with no attempt to relieve anybody from anything at any time.” This is evident in his technical approach, as well. Lubitsch’s usually airy style is similarly blended with other styles to meet the film’s unique demands. When Lubitsch first follows Sobinski into the RAF, the almost documentary training sequence that follows looks like a montage from a war movie. During the Professor’s escape and death sequence, he runs frantically into the Polski Theater, crawling between seats as the spotlight searches like it might during a prison break, or more aptly, a concentration camp. As his pursuers close in, he dashes for the stage and freezes when the spotlight catches him, like some pitch-perfect shot out of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller. When he’s finally shot dead, it happens behind the curtain, which then rises on his poetic collapse. These sequences and plot elements are far too brave, sophisticatedly filmed, and intricately conceived to waive the film off as a comic trifle.

Still, as Greenberg mentions, “A laugh is nothing to be sneezed at.” Not just because his subject demands it, Lubitsch elevates his film’s farcical qualities to high comedy through his omnipresent “Lubitsch Touch”—an oft-pondered term created to transform the filmmaker into a brand name, no different than Hitchcock’s posturing label as “Master of Suspense.” Hitchcock’s status as Master is just that: an unconditional rank of prominence. But Lubitsch’s Touch remains an ambiguous idea, yet more than just the hint of sophistication and class he brings to every project. We see it when, amid the Nazi suspense, the director doesn’t forget to acknowledge Joseph’s petty actor’s ego or jealousy toward his wife. Or when Lubitsch manages to simplify To Be or Not to Be’s several ongoing plot elements into a single moment, when Bronski’s Hitler interrupts Ehrhardt’s advances on Maria. Traces of his personal style are heard in the endless wit. They are arranged within hilarious and multi-layered situations. They’re seen in the poignant gag where Bronski goes unnoticed until he dons Hitler’s mustache. The Lubitsch Touch concealed sex but skillfully kept the topic in the forefront; it treated human flaws gracefully; it economized complicated plotlines into simple matters and often crystallized whole films into a single moment. More important than any of these qualities was Lubitsch’s ability to imbue his audience with a sense of knowingness toward jokes that fluctuate between mere delicate hints and rousing, hilarious blowouts, and we never once feel guilty for laughing.

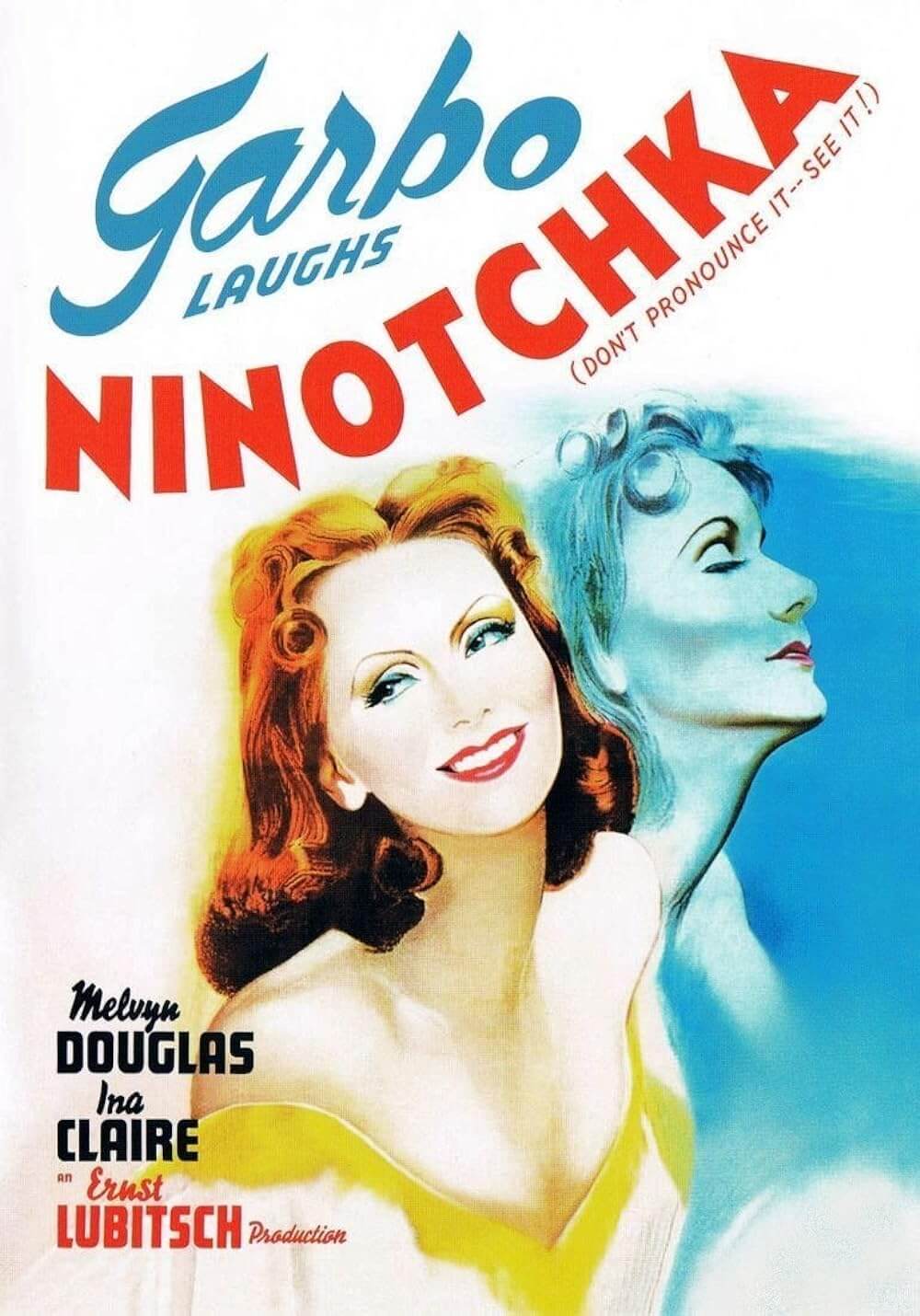

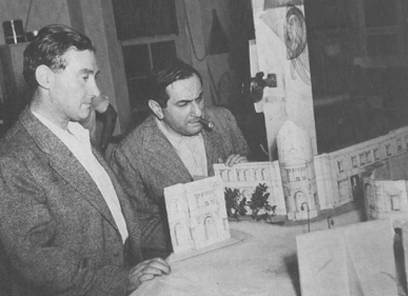

Many Lubitsch pictures were based on obscure European plays or stories, but To Be or Not to Be was an original idea developed by Lubitsch and Hungarian writer Melchior Lengyel, who also helped develop the idea behind the director’s Ninotchka (1939). Their proposed outline contained all the overlapping strains of espionage and farcical comedy, and screenwriter Edwin Justus Mayer, a black comedy intellectual and frequent financial failure, brought their scenario to life. Alexander Korda produced the picture under the United Artists label. He chose to make the film in America instead of his home in England, as with many of his wartime productions, including That Hamilton Woman (1941) and Jungle Book (1942). Korda was believed to be a British agent at the time. If this is true, his Hollywood ties must have afforded him some important information; after the war ended, he was mysteriously knighted for his contributions to the war effort. Alexander’s younger brother Vincent designed To Be or Not to Be’s sets, including bombed Warsaw streets, the Polski Theater, and both the staged and “real” versions of Gestapo headquarters. Vincent’s version of Gestapo HQ is perhaps the era’s best; he avoids the bare, utilitarian offices seen in so many WWII films or even on the Polski stage. Rather, he emphasizes the theatricality of the Nazis through ornate decorations and paintings, which was so much more accurate both historically and thematically for the film.

Many Lubitsch pictures were based on obscure European plays or stories, but To Be or Not to Be was an original idea developed by Lubitsch and Hungarian writer Melchior Lengyel, who also helped develop the idea behind the director’s Ninotchka (1939). Their proposed outline contained all the overlapping strains of espionage and farcical comedy, and screenwriter Edwin Justus Mayer, a black comedy intellectual and frequent financial failure, brought their scenario to life. Alexander Korda produced the picture under the United Artists label. He chose to make the film in America instead of his home in England, as with many of his wartime productions, including That Hamilton Woman (1941) and Jungle Book (1942). Korda was believed to be a British agent at the time. If this is true, his Hollywood ties must have afforded him some important information; after the war ended, he was mysteriously knighted for his contributions to the war effort. Alexander’s younger brother Vincent designed To Be or Not to Be’s sets, including bombed Warsaw streets, the Polski Theater, and both the staged and “real” versions of Gestapo headquarters. Vincent’s version of Gestapo HQ is perhaps the era’s best; he avoids the bare, utilitarian offices seen in so many WWII films or even on the Polski stage. Rather, he emphasizes the theatricality of the Nazis through ornate decorations and paintings, which was so much more accurate both historically and thematically for the film.

Lubitsch shot with near-complete creative control, as usual, answerable only to the sensor boards and his friend Alexander Korda. The director cast several actors from his regular troupe, among them Bressart, Ruman, and Charles Halton. His initial choice for Maria Tura was Miriam Hopkins, star of Trouble in Paradise and Design for Living, but she demanded the role be expanded, and the director refused, so she turned down the part. Carole Lombard was cast in her place, and it would be her last screen appearance; she died in a plane crash in January 1942 while returning from a WWII bond-selling tour with her mother. Jack Benny had been a major star on radio and later television, noted for his comic use of pauses and signature meanness, but he never broke out into film in a big way. To Be or Not to Be would be his most significant role. Behind the camera was Rudolph Maté, who photographed Laurel and Hardy’s Our Relation (1936) and Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940), two films that when combined prepared Maté to make this WWII spy comedy. Before shooting a scene, Lubitsch famously acted out every part for his cast, his performances absurdly bad; he was not a skilled actor, despite his origins on the stage and in a series of comedic short films. Actors used Lubitsch’s rendition to gauge how much more restrained their performance should be in comparison. Lubitsch’s sense of joy toward comedy prevailed behind the camera as well. In one behind-the-scenes story, Benny recalled seeing Lubitsch with a handkerchief stuffed in his mouth to muffle his own laughing—jokes he had helped write and probably had seen rehearsed several times still cracked him up.

Critics and many moviegoers weren’t amused and described the film as “callous” and “inexcusable” in their assessments. Several reviewers pointed out their anger over specific lines of dialogue. One crack was made by Joseph as he impersonates Col. Ehrhardt for the Professor, saying, “We do the concentrating and the Poles do the camping.” Another, spoken by Ehrhardt as he quips about Joseph Tura’s acting, goes: “What he did to Shakespeare, we are doing now to Poland.” Even Lubitsch’s friends encouraged him to remove that line from the finished film, but that would have meant removing the film’s edge. These remain two of the most hilariously unrepentant lines in comedy history. Representative of most appraisals of the period is C.A. Lejeune’s write-up in The Observer, which states, “To my mind, a farce set against the agonies of bombed Warsaw is in the poorest of tastes, especially as the film makes no attempt to ignore them.” Lejeune’s statement forces one to wonder if she felt such atrocities should be ignored. A case could certainly be made that the world’s late-to-respond position on Hitler resulted in more tragedy than was necessary. At any rate, Lejeune’s remarks also question if the healing power of laughter is enough to mend what were then the open wounds of Auschwitz. Lubitsch refuses to disguise the ugly truth of the situation, and only a few critics recognized how rare this was. Though Werner R. Heymann’s score was nominated for an Academy Award, it would take over twenty years for the film to be reconsidered and appreciated as the masterpiece it is. Time alone healed the Holocaust’s wounds into ugly scars and allowed To Be or Not to Be’s reassessment among critics and film historians. Once the picture was revisited, film historians began to look back on Lubitsch’s career and see the genius and nerve within this film. In 1982, Mel Brooks starred in an unfortunate and overwrought remake of To Be or Not to Be, while Lubitsch’s film was more recently acknowledged on AFI’s “100 Years… 100 Laughs” list.

Critics and many moviegoers weren’t amused and described the film as “callous” and “inexcusable” in their assessments. Several reviewers pointed out their anger over specific lines of dialogue. One crack was made by Joseph as he impersonates Col. Ehrhardt for the Professor, saying, “We do the concentrating and the Poles do the camping.” Another, spoken by Ehrhardt as he quips about Joseph Tura’s acting, goes: “What he did to Shakespeare, we are doing now to Poland.” Even Lubitsch’s friends encouraged him to remove that line from the finished film, but that would have meant removing the film’s edge. These remain two of the most hilariously unrepentant lines in comedy history. Representative of most appraisals of the period is C.A. Lejeune’s write-up in The Observer, which states, “To my mind, a farce set against the agonies of bombed Warsaw is in the poorest of tastes, especially as the film makes no attempt to ignore them.” Lejeune’s statement forces one to wonder if she felt such atrocities should be ignored. A case could certainly be made that the world’s late-to-respond position on Hitler resulted in more tragedy than was necessary. At any rate, Lejeune’s remarks also question if the healing power of laughter is enough to mend what were then the open wounds of Auschwitz. Lubitsch refuses to disguise the ugly truth of the situation, and only a few critics recognized how rare this was. Though Werner R. Heymann’s score was nominated for an Academy Award, it would take over twenty years for the film to be reconsidered and appreciated as the masterpiece it is. Time alone healed the Holocaust’s wounds into ugly scars and allowed To Be or Not to Be’s reassessment among critics and film historians. Once the picture was revisited, film historians began to look back on Lubitsch’s career and see the genius and nerve within this film. In 1982, Mel Brooks starred in an unfortunate and overwrought remake of To Be or Not to Be, while Lubitsch’s film was more recently acknowledged on AFI’s “100 Years… 100 Laughs” list.

Today, to truly grasp how heroic and uncommon a picture Lubitsch made, the film must be regarded through the prism of history, particularly in its representation of Nazis. Lubitsch and Mayer knew exactly what was going on in Europe. As such, they depict Nazis as ludicrous by refusing to represent them in an intimidating light or dwell on their atrocities. Of his film, Lubitsch said, “No actual torture chamber is photographed, no flogging is shown, no close-up of excited Nazis using whips and rolling their eyes in lust. My Nazis are different: they passed that stage long ago. Brutality, floggings and torture have become their daily routine.” The director needs not to remind us through demonstration how vile and dangerous the Nazis were; this we know already. Rather, he puts a human face on Nazis, showing them not as the inhuman monsters Hollywood usually showed them to be, but by classifying them more realistically. Lubitsch’s Nazis are weak-minded and buffoonish people, ever frightened of their overseer, and prone to interrupting conversational lulls with an enthusiastic-if-discomfited “Heil Hitler!” Lubitsch reminds us that these men are not monsters, and we should not think of them as such; doing so only gives them power. By portraying them as incompetent, Lubitsch strikes a much more severe blow to the Nazi philosophy.

Consider Col. Ehrhardt, portrayed by Ruman as a nervous, bug-eyed, walrus-mustached nincompoop. Before he appears onscreen, references to the Colonel have built him up into an incredible monster. When we finally meet him, of course, we discover Ehrhardt to be bungling and idiotic. What does it say about the superior who promoted such a man or those who blindly follow his orders? In a way, Ehrhardt is terrifying because he is a man of power—a glorious simpleton capable of sending someone to their death. We should be frightened of him, not in the way we would be frightened of a criminal mastermind, but in the way, one might fear an angry child with a loaded gun. That Lubitsch can turn such a character into a source of laughs is part of his brilliance. When Joseph performs as Ehrhardt for the Professor, it becomes riotous when he’s suddenly incapable of improvisation. In London, the Professor quips that they call the Colonel “Concentration Camp Ehrhardt,” and Joseph can only respond, again and again, “So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt, eh?” When we finally meet the real Ehrhardt, how hilarious it is to discover he’s even more absurd than Joseph’s depiction of him. Acting as the Professor now, Joseph tells Ehrhardt what they call him in London, and in similar breaks in the conversation, the real Ehrhardt falls back on “So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt, eh?”

Consider Col. Ehrhardt, portrayed by Ruman as a nervous, bug-eyed, walrus-mustached nincompoop. Before he appears onscreen, references to the Colonel have built him up into an incredible monster. When we finally meet him, of course, we discover Ehrhardt to be bungling and idiotic. What does it say about the superior who promoted such a man or those who blindly follow his orders? In a way, Ehrhardt is terrifying because he is a man of power—a glorious simpleton capable of sending someone to their death. We should be frightened of him, not in the way we would be frightened of a criminal mastermind, but in the way, one might fear an angry child with a loaded gun. That Lubitsch can turn such a character into a source of laughs is part of his brilliance. When Joseph performs as Ehrhardt for the Professor, it becomes riotous when he’s suddenly incapable of improvisation. In London, the Professor quips that they call the Colonel “Concentration Camp Ehrhardt,” and Joseph can only respond, again and again, “So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt, eh?” When we finally meet the real Ehrhardt, how hilarious it is to discover he’s even more absurd than Joseph’s depiction of him. Acting as the Professor now, Joseph tells Ehrhardt what they call him in London, and in similar breaks in the conversation, the real Ehrhardt falls back on “So they call me Concentration Camp Ehrhardt, eh?”

Within Lubitsch’s career, the film stands out as something altogether unique. Surely To Be or Not to Be contains familiar Lubitsch comic devices, such as his prevalent use of love triangles, here seen between Joseph, Maria, and Sobinski. And in many ways, Ninotchka anticipates this film politically, being about Greta Garbo’s Communist character having a romantic awakening in Paris. Here, despite his frequently humanist efforts, Lubitsch’s use of suspense and poetic nods to Shakespeare is distinct in his career, with an immediate sense of humanity pouring out of this film like it never had in Lubitsch’s work before. The viewer can feel the filmmaker’s passion within the picture’s message, particularly during the scene where Greenberg finally gets to play Shylock and Bressart all but directly addresses the audience in defense of Jewish rights. The scene cannot help but recall a similar speech given at the end of Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, another Nazi satire released the year before. Hitler’s crimes against humanity inspired cinema’s comedians to fight back with their unique arsenal: humor. It’s strange but true that humor proves a more effective weapon within the film than tragedy alone. You can feel Lubitsch and Mayer just sharpening their comic smarts throughout the picture for every jab against the Nazis, each blow deeper than the last.

Throughout To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch orchestrates a comic work of art whose central theme of acting offers perhaps the most accurate assessment of and staggering blow against the Nazi movement ever put to film. In performing like Nazis, the actors of the Polski Theater must adopt an embellished theatrical style to fool the enemy; and yet, Ehrhardt is even more over-the-top because he pretends his authority is genuine, even while he hysterically cowers at the thought of Hitler. By pairing stage actors against Nazis who play the part of monsters, and then suggesting these actors must behave in farcical ways to pass as Nazis and survive, Lubitsch plays with notions of reality and theater, and by the end of his film resolves that the Nazis too are simply actors on a stage. This interplay of reality and theatricality aligns his film’s absurdist Nazi behavior with real life, whereas the Polski troupe’s stage performances are knowingly artificial; still, they’re both gross exaggerations and silly for the viewer, which thereupon delivers a staggeringly refined insult to Nazis. By implying Nazis are just actors on the world stage, Lubitsch discredits their most effective and intimidating weapon, their theatricality, and strikes a staggering blow through the art of cinema. Making To Be or Not to Be when he did, the way he did, was a daring and courageous move, and the film has survived the test of time to validate Lubitsch’s risk. Whether viewed in a historical context or merely for laughs, Ernst Lubitsch made an exceptional and layered comedy, timeless in its commentary, elegance, and sophistication.

Throughout To Be or Not to Be, Lubitsch orchestrates a comic work of art whose central theme of acting offers perhaps the most accurate assessment of and staggering blow against the Nazi movement ever put to film. In performing like Nazis, the actors of the Polski Theater must adopt an embellished theatrical style to fool the enemy; and yet, Ehrhardt is even more over-the-top because he pretends his authority is genuine, even while he hysterically cowers at the thought of Hitler. By pairing stage actors against Nazis who play the part of monsters, and then suggesting these actors must behave in farcical ways to pass as Nazis and survive, Lubitsch plays with notions of reality and theater, and by the end of his film resolves that the Nazis too are simply actors on a stage. This interplay of reality and theatricality aligns his film’s absurdist Nazi behavior with real life, whereas the Polski troupe’s stage performances are knowingly artificial; still, they’re both gross exaggerations and silly for the viewer, which thereupon delivers a staggeringly refined insult to Nazis. By implying Nazis are just actors on the world stage, Lubitsch discredits their most effective and intimidating weapon, their theatricality, and strikes a staggering blow through the art of cinema. Making To Be or Not to Be when he did, the way he did, was a daring and courageous move, and the film has survived the test of time to validate Lubitsch’s risk. Whether viewed in a historical context or merely for laughs, Ernst Lubitsch made an exceptional and layered comedy, timeless in its commentary, elegance, and sophistication.

Bibliography:

Barnes, Peter. To Be or Not to Be. (BFI Modern Classics). London: British Film Institute, 2002.

Eyman, Scott. Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review