The Definitives

There Will Be Blood

Essay by Brian Eggert |

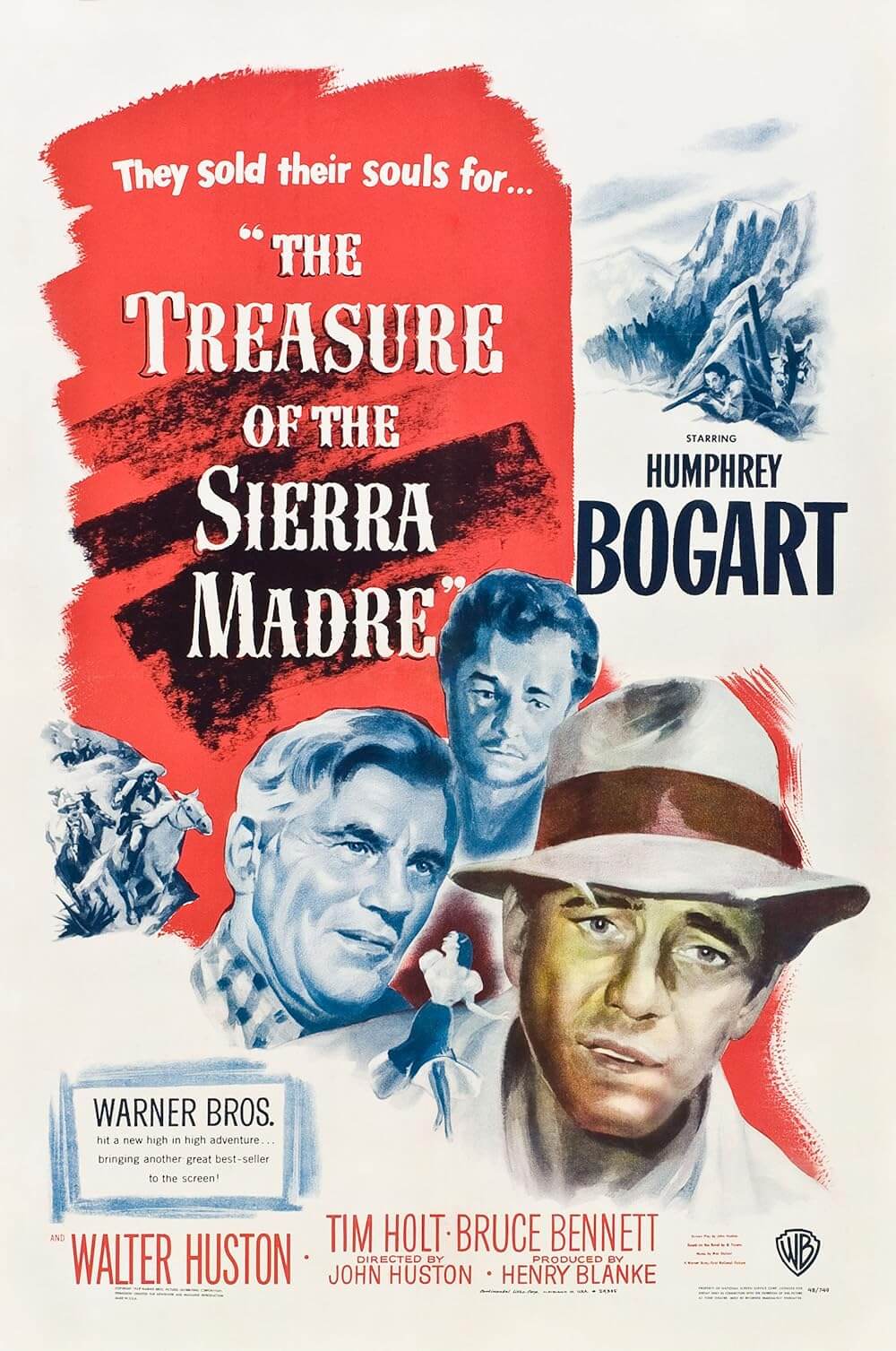

Manifest Destiny once signified the American persona and compelled settlers to cross punishing terrain in a professed duty of expansionism. On the pretense of a national movement, or perhaps a moral mission in the name of religion, countless pioneers rode into unforgivable country, endured dismal conditions, and risked their lives for a grand ideal. At the center of Manifest Destiny was an impetus that was neither a nationalistic nor nobly philosophical cause; rather, it was determined by self-interest. Specifically, beyond the Western Frontier, explorers had the freedom to prospect for limitless wealth and enjoy untold personal freedoms to create their own self-benefitted world. It was perhaps the most American period in the country’s history. In cinema, Western pictures romanticize these dreamy ideas, even as they show us the depths to which men will sink to achieve their own idea of success. Westerns put forward Nietzschean characters so desperate to succeed that all other ties are secondary, morality among them. They depict an all-consuming desire to succeed; they show ambition progressing beyond greed to reach extreme heights of narcissism, to what might be called villainy; they feature characters willing to lie, cheat, murder, and manipulate to achieve their idea of prosperity. Amid this genre’s representations are Western characters who have personified the moral corruption brought about by the notion of Manifest Destiny, from Walter Brennan’s cruel rustler in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946) to Humphrey Bogart’s maddened prospector in John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948).

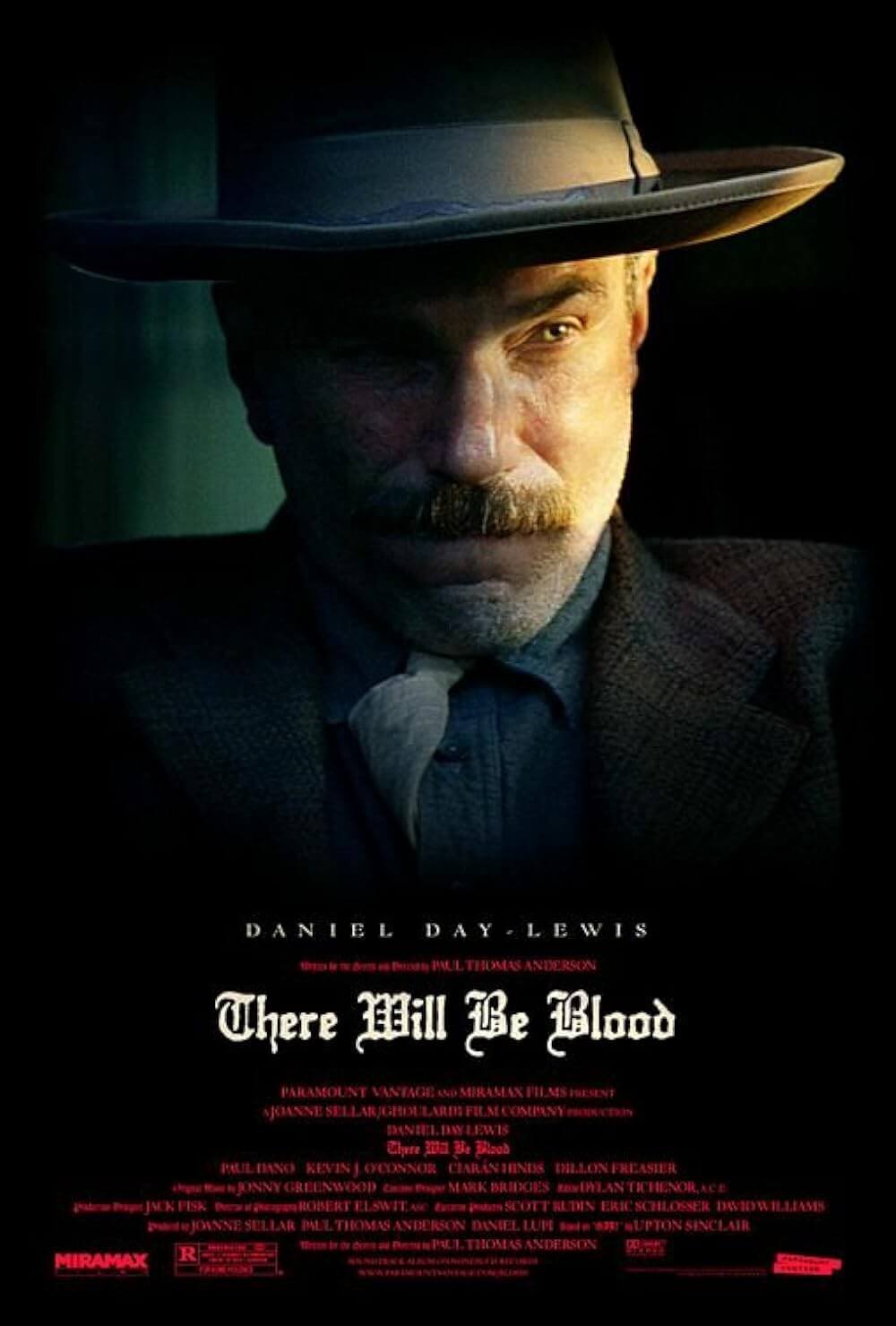

Few Westerns have reached so deep into the abscesses of American ambition as thoroughly as Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. Anderson’s film takes place at the turn of the last century, as the frontier gradually gave way to industrialization, and tells the story of two men with dissimilar methods of making their fortune. Anderson’s 2007 picture shows the frontier as a rugged place where Daniel Day-Lewis’ tireless oil prospector Daniel Plainview applies his grit and unyielding determination, both physically and in his business dealings. As Plainview says, “I have a competition in me; I want no one else to succeed… I hate most people… There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking.” He remains a raw man of unprincipled Nature, whose hatred of people and ambition to be left alone—“to get away from all these… people”—push him beyond the meager constraints of moral views. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche found conventional morality objectionable, as it weakened the innate strength and power in human beings afforded by Nature. Plainview is a pure Nietzschean protagonist; in his Oscar-winning performance, Day-Lewis even looks like Nietzsche behind his thick, bushy mustache. Plainview understands moral codes as nothing more than obstacles that, through his willpower to ignore them, he can easily avoid. But it’s more than merely navigating morality; Plainview despises morals as signs of weakness. And though his ambition leaves him misanthropic and achingly lonely, his overarching desire for a pointedly American symbol of success, namely oil and the isolationist comforts it affords, circumvents all else.

Anderson first introduces Daniel Plainview in 1898, a raw man who sets out into Nature to conquer it and make his fortune on precious metals. He is primal and pure. Barely more than a single word of dialogue is spoken for the first 20 minutes of the film. Plainview’s words mean nothing until he has some measure of success. Within that blissfully shot, near-silent opening, we hear but one word, uttered to punctuate Plainview’s desire: “No!”—spoken when his find is threatened by a broken leg. Nevertheless, he drags himself to the claims office on his back. After years of successful mining, Plainview begins prospecting for oil. These early scenes play like the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where pre-humans raise their tools in the air and worship a mysterious black monolith; except, Plainview raises his hand covered in crude oil, and the monolith remains a rod slicked in black. When one of his workers dies in an accident, he adopts the worker’s orphaned baby, named H.W. Not until 11 years have passed in the story do we finally hear Plainview speak. He describes himself as an oil man traveling around with his young son H.W. (Dillon Freasier), managing his many oil fields, and seeking out land leases to buy and prospect, the profits from which help their respective communities thrive. His wife, he says, died during childbirth. It becomes evident, at least to the audience, that Plainview’s “child” is just another tool of the trade, even if the boy affords our protagonist some relief from solitude.

Anderson first introduces Daniel Plainview in 1898, a raw man who sets out into Nature to conquer it and make his fortune on precious metals. He is primal and pure. Barely more than a single word of dialogue is spoken for the first 20 minutes of the film. Plainview’s words mean nothing until he has some measure of success. Within that blissfully shot, near-silent opening, we hear but one word, uttered to punctuate Plainview’s desire: “No!”—spoken when his find is threatened by a broken leg. Nevertheless, he drags himself to the claims office on his back. After years of successful mining, Plainview begins prospecting for oil. These early scenes play like the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where pre-humans raise their tools in the air and worship a mysterious black monolith; except, Plainview raises his hand covered in crude oil, and the monolith remains a rod slicked in black. When one of his workers dies in an accident, he adopts the worker’s orphaned baby, named H.W. Not until 11 years have passed in the story do we finally hear Plainview speak. He describes himself as an oil man traveling around with his young son H.W. (Dillon Freasier), managing his many oil fields, and seeking out land leases to buy and prospect, the profits from which help their respective communities thrive. His wife, he says, died during childbirth. It becomes evident, at least to the audience, that Plainview’s “child” is just another tool of the trade, even if the boy affords our protagonist some relief from solitude.

For small towns that might be swept away by big oil companies, Plainview’s business tact seems more human, more reasonable than the alternative. Viewers of There Will Be Blood nonetheless see how Plainview has carefully designed his façade for maximum small town appeal; and while Plainview’s approach may indeed result in riches for these communities, that result is less an intended consequence of his business than a necessary evil. Eventually, Plainview is approached by Paul Sunday (Paul Dano), a sharp young man from a family of poor goat farmers who asks for $500 for information on a massive potential lease in the untouched territory of Little Boston. Impressed by Paul’s cut-and-dry negotiation, Plainview happily pays the asking price and without delay heads to Little Boston. There, he must negotiate with Abel Sunday (David Willis), Paul’s dim father. We also meet Eli Sunday (also Dano) for the first time; Eli is Paul’s identical twin and, in terms of sheer directness, Paul’s antithesis. More than Abel, Eli seems to understand the value of his family’s acreage in Little Boston; he asks for $5,000 upfront and another $5,000 after the oil begins pumping. When Plainview asks what Eli will use the money for, Eli replies it’s for his growing church, at which he posits himself a healer and vessel for God. Plainview looks at him, smiles, and says, “That’s good. That’s a good one,” as if to acknowledge that, like his own oil business, Eli too has created an enterprise for himself. They strike a deal.

Within weeks, Plainview has ripened the proposed land, asserting himself as the progenitor of this once-dead town, now thriving with employment, irrigation, a school, and agriculture because of his oil project. Long deprived of grain, Little Boston’s citizens now have bread on their table because of Plainview. Still, all is not without incident: a fatal accident occurs at the well and kills a worker, and another accident leaves H.W. deaf. Eli blames the incidents on Plainview’s refusal to allow him to bless the well. To be sure, Eli has become a spiteful adversary, and for this Plainview knocks him down in the mud, humiliates him, slaps him in the face, and declares, “I’m going to bury you, Eli.” Meanwhile, Plainview’s eventual domination of Little Boston hinges on arranging practical transport for the oil sea flowing under the town. To do this, he must acquire a final lease held by William Bandy (Hans Howes); Plainview intends to build a pipeline through Bandy’s land, reaching one hundred miles to the ocean—a less expensive option than shipping by way of railroad. Standard Oil approaches him with an alternate proposal: settle out for one million dollars so they can transport the oil via railroad, which they own. A representative suggests Plainview should take the money and look after his deaf son. To the audacity that someone would advise him how to run his family, Daniel responds, “One night, I’m gonna come inside your house, wherever you’re sleeping, and I’m gonna cut your throat.”

Within weeks, Plainview has ripened the proposed land, asserting himself as the progenitor of this once-dead town, now thriving with employment, irrigation, a school, and agriculture because of his oil project. Long deprived of grain, Little Boston’s citizens now have bread on their table because of Plainview. Still, all is not without incident: a fatal accident occurs at the well and kills a worker, and another accident leaves H.W. deaf. Eli blames the incidents on Plainview’s refusal to allow him to bless the well. To be sure, Eli has become a spiteful adversary, and for this Plainview knocks him down in the mud, humiliates him, slaps him in the face, and declares, “I’m going to bury you, Eli.” Meanwhile, Plainview’s eventual domination of Little Boston hinges on arranging practical transport for the oil sea flowing under the town. To do this, he must acquire a final lease held by William Bandy (Hans Howes); Plainview intends to build a pipeline through Bandy’s land, reaching one hundred miles to the ocean—a less expensive option than shipping by way of railroad. Standard Oil approaches him with an alternate proposal: settle out for one million dollars so they can transport the oil via railroad, which they own. A representative suggests Plainview should take the money and look after his deaf son. To the audacity that someone would advise him how to run his family, Daniel responds, “One night, I’m gonna come inside your house, wherever you’re sleeping, and I’m gonna cut your throat.”

Though Plainview seems to use everyone around him for personal gain, foremost H.W., his genuine anger toward the Standard Oil man suggests that Plainview has some measure of emotional attachment to H.W., although that need comes secondary to his ambition. This is what makes him a compelling, even tragic monster, and not without emotion. His reaction to his son’s accident, for example, is one of fatherly concern, but less than his desire to contain the burning oil spring that caused it. As a gas blowout catches fire and burns from the earth, Plainview’s assistant Fletcher (Ciarán Hinds) asks, “H.W. okay?” Plainview replies unemotionally, “No, he isn’t”—his eyes never breaking from the fire that represents his future prosperity. H.W.’s injury is no less an acceptable part of hard work than Plainview’s broken leg in the film’s earliest scenes. Later, a man named Henry (Kevin J. O’Connor) arrives and claims to be Plainview’s half-brother, the son of his father and another woman. Plainview soon drops his guard with Henry, and he feels a much-needed connection. That connection is enough so H.W. grows jealous and, compounded by the frustration of his hearing loss, he must be sent away—a decision Plainview regrets, but it must be done. What is more, Plainview now feels a familial connection to Henry, who he sees as someone to take over once he can finally “get away from all these… people.” Tragically, Plainview begins to suspect Henry and discovers the man is an imposter, and Plainview’s murderous reaction speaks to his sense of betrayal, revealing his vulnerability to loneliness, but also sending him on an even more narcissistic path that propels his isolationism and hatred of people beyond graphic threats.

After murdering Henry and burying his body one night, Plainview is confronted by Bandy, who witnessed the entire scene. Bandy demands that Plainview repent and be baptized in Eli’s church. Out of necessity, Plainview must swallow his Pyrrhonism, however thinly. Keeping up the veneer and barely suppressing his hatred of religion, he arrives at Eli’s church in arguably the film’s best scene. Eli finally has the upper hand and he exploits it fully, taking every advantage. Plainview must tolerate the outlandish scene to maintain his front, since refusing Bandy and Eli at this point would put his enterprise at risk. He indulges Eli’s fervent Christian ramblings about “the blood”, making the community’s representative feel like he has won, if only so later on the faux victory can be used against the righteous servant. Eli doesn’t make it easy. “Oh, Daniel,” he says. “You’ve come here and you’ve brought good and wealth, but you have also brought your bad habits as a backslider… You have abandoned your child—your child that you raised. You have abandoned all because he was sick and you have sinned.” Eli forces Plainview to proclaim, “I am a sinner!” and with much anger “I have abandoned my child!” again and again, the moment working over our protagonist on multiple levels. Foremost, he disdains the transparency of the religious showmanship, muttering “let me get out of here” to himself, while another part of him harbors his hatred for Eli. Another part still aches because, to be sure, he abandoned H.W. and feels conflicted about it. As the scene continues, Eli slaps him across the face, trying to humiliate Plainview as he was humiliated in the mud, but Plainview endures. Finally, the baptism is over, and he shakes off the water like a cartoon mutt, grinning a wry smirk.

After murdering Henry and burying his body one night, Plainview is confronted by Bandy, who witnessed the entire scene. Bandy demands that Plainview repent and be baptized in Eli’s church. Out of necessity, Plainview must swallow his Pyrrhonism, however thinly. Keeping up the veneer and barely suppressing his hatred of religion, he arrives at Eli’s church in arguably the film’s best scene. Eli finally has the upper hand and he exploits it fully, taking every advantage. Plainview must tolerate the outlandish scene to maintain his front, since refusing Bandy and Eli at this point would put his enterprise at risk. He indulges Eli’s fervent Christian ramblings about “the blood”, making the community’s representative feel like he has won, if only so later on the faux victory can be used against the righteous servant. Eli doesn’t make it easy. “Oh, Daniel,” he says. “You’ve come here and you’ve brought good and wealth, but you have also brought your bad habits as a backslider… You have abandoned your child—your child that you raised. You have abandoned all because he was sick and you have sinned.” Eli forces Plainview to proclaim, “I am a sinner!” and with much anger “I have abandoned my child!” again and again, the moment working over our protagonist on multiple levels. Foremost, he disdains the transparency of the religious showmanship, muttering “let me get out of here” to himself, while another part of him harbors his hatred for Eli. Another part still aches because, to be sure, he abandoned H.W. and feels conflicted about it. As the scene continues, Eli slaps him across the face, trying to humiliate Plainview as he was humiliated in the mud, but Plainview endures. Finally, the baptism is over, and he shakes off the water like a cartoon mutt, grinning a wry smirk.

Both men use religion as a tool, though it remains Eli’s primary instrument. Consider how Plainview asks Eli to give his dead worker a Christian burial merely out of an obligation to keep his employees and Little Boston content and making money; it’s the same reason he submits himself to Eli’s baptism. And yet, both remain equally determined to acquire riches and power. If Plainview is the embodiment of Nietzsche’s views on using one’s natural powers to achieve their own self-interest, then Eli represents Nietzsche’s view on religion. Nietzsche saw religion as another tool to remove obstacles in one’s path, but also a method employed by the weak and powerless to make life more tolerable—they forego striving in this life for what he called “faith in ‘another’ or ‘better’ life”. Nietzsche also argued, “The reverse side of Christian compassion for the suffering of one’s neighbor is a profound suspicion of all the joy of one’s neighbor, of his joy in all that he wants to do and can.” To be sure, Eli wants the same prosperity as Plainview for himself and resents Plainview for not making him a partner; however, Eli has neither the ability nor inclination to get his hands dirty to perform the necessary work. Eli’s goal is ultimately the same as Plainview’s, but his approach uses religion to manipulate Plainview’s workers through their piety. When Plainview refuses to cooperate, then, with unmeasured hypocrisy, Eli knowingly uses the masses and his moral rationalizations to exact pressure on Plainview and his Church of the Third Redeemer. In his evident duplicitousness, Eli rationalizes his selfish interests through religion. It’s a tactic Plainview might admire were it not so annoying to him personally.

Throughout the film, Dano creates livid outbursts during Eli’s religious sermons, but none so outrageous as the baptism scene. Originally, Anderson hired another actor (Kel O’Neill) as Eli. Three weeks of shooting later, Anderson saw how Day-Lewis’ method acting intimidated O’Neill and hindered the performance. Dano was hired as a replacement and found himself inspired by Day-Lewis’ famous dedication. Watch the brimming moment when Plainview knocks Eli into the mud, hysterically slapping him across the face like a cruel schoolyard bully. Watch how both men seem to know that the other is a charlatan, working to get the upper hand; each has their moment of victory, both piercing, to reflect their respective monstrosity. For Day-Lewis’ performance, Anderson wanted him to draw from John Huston’s crooked posture and vocal cadence and insisted the actor watch The Treasure of the Sierra Madre for inspiration. Huston’s low-toned, direct voice (seen in Chinatown, 1974) can indeed be heard in Day-Lewis’ performance, but not so much that we feel a caricature or impersonation was developed. Plainview remains an invention comprised of obsession and hatred for the weaker people around him. Watch Day-Lewis brood as he does; watch how the ever-working cogs in Plainview’s head, eyes, and on his brow are always working. Even in seemingly idle scenes, Day-Lewis is altogether active, a swell of energy and rage fluctuating beneath the surface. The process is at once excruciating, frightening, and exhilarating to behold, as the established method actor moves beyond representation into full-on embodiment of this calculating, hard-skinned character. Day-Lewis and Dano complement each other perfectly.

Throughout the film, Dano creates livid outbursts during Eli’s religious sermons, but none so outrageous as the baptism scene. Originally, Anderson hired another actor (Kel O’Neill) as Eli. Three weeks of shooting later, Anderson saw how Day-Lewis’ method acting intimidated O’Neill and hindered the performance. Dano was hired as a replacement and found himself inspired by Day-Lewis’ famous dedication. Watch the brimming moment when Plainview knocks Eli into the mud, hysterically slapping him across the face like a cruel schoolyard bully. Watch how both men seem to know that the other is a charlatan, working to get the upper hand; each has their moment of victory, both piercing, to reflect their respective monstrosity. For Day-Lewis’ performance, Anderson wanted him to draw from John Huston’s crooked posture and vocal cadence and insisted the actor watch The Treasure of the Sierra Madre for inspiration. Huston’s low-toned, direct voice (seen in Chinatown, 1974) can indeed be heard in Day-Lewis’ performance, but not so much that we feel a caricature or impersonation was developed. Plainview remains an invention comprised of obsession and hatred for the weaker people around him. Watch Day-Lewis brood as he does; watch how the ever-working cogs in Plainview’s head, eyes, and on his brow are always working. Even in seemingly idle scenes, Day-Lewis is altogether active, a swell of energy and rage fluctuating beneath the surface. The process is at once excruciating, frightening, and exhilarating to behold, as the established method actor moves beyond representation into full-on embodiment of this calculating, hard-skinned character. Day-Lewis and Dano complement each other perfectly.

Accenting the performances is the equally haunting score by Radiohead’s lead guitarist Jonny Greenwood, of whom Anderson was a fan before filming began. Greenwood initially had doubts about scoring the picture, but Anderson insisted, convinced that the score would be as unique as his band’s sound. With relentless tempos and atmospheric dread, Greenwood’s sharp cinematic score manifests with haunting energy, combined with ethereal, cutting sounds and playful overlapping percussions, yet always classicized. Greenwood’s music swells, making Anderson’s nearly three-hour picture move forward with an ever-booming pace. Equally as epic, cinematographer Robert Elswit delivers Oscar-winning visuals. Elswit shot all of Anderson’s films before and after There Will Be Blood, with the exception of The Master (2012). Filming with anamorphic lenses in the American Southwest, Elswit avoids digital trickery and instead captures the sizzling beauty of the landscape or the rugged, ligneous reality of production designer Jack Fisk’s Little Boston sets. Elswit also uses natural light, shooting night scenes lit by campfire or, in one spectacular-looking scene, by the light of a blazing oil fire bursting from the ground like a spire from Hell. The sweaty, earthen look of There Will Be Blood remains both Anderson and Elswit’s finest looking motion picture.

Anderson based his screenplay on the first 150-pages of Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, but he detracted from the source material enough to warrant a title change and “inspired by” source credit. Sinclair loosely based his Daniel Plainview character on Edward Doheny, the turn-of-the-century precious metals prospector who dug himself into pitch, thus oil, eventually becoming head of PanAmerican Petroleum and Transport Company. Anderson enlarges Doheny’s more eccentric, Charles Foster Kane-isms; for example, Doheny’s humungous Xanadu-like ranch in California called Greystone Mansion, complete with an in-house bowling alley, is not unlike Plainview’s palace in the film’s last scenes. And as suggested, Anderson’s influence also derives from John Huston, be it from his filmic work or larger-than-life off-screen persona. According to an interview with the New York Times, when he was writing, Anderson would put The Treasure of the Sierra Madre on in the background and even sleep with it playing for inspiration. Huston’s film is an archetypal examination of greed’s insatiability. Humphrey Bogart starred alongside Walter Huston and Tim Holt as desperate men whose sudden gold strike tears them apart with violent suspicion and paranoia. However, no prospector or money-hungry tycoon ever depicted on film, not even Charles Foster Kane or Gordon Gekko, matches the intensity and savagery of Daniel Plainview.

Anderson based his screenplay on the first 150-pages of Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, but he detracted from the source material enough to warrant a title change and “inspired by” source credit. Sinclair loosely based his Daniel Plainview character on Edward Doheny, the turn-of-the-century precious metals prospector who dug himself into pitch, thus oil, eventually becoming head of PanAmerican Petroleum and Transport Company. Anderson enlarges Doheny’s more eccentric, Charles Foster Kane-isms; for example, Doheny’s humungous Xanadu-like ranch in California called Greystone Mansion, complete with an in-house bowling alley, is not unlike Plainview’s palace in the film’s last scenes. And as suggested, Anderson’s influence also derives from John Huston, be it from his filmic work or larger-than-life off-screen persona. According to an interview with the New York Times, when he was writing, Anderson would put The Treasure of the Sierra Madre on in the background and even sleep with it playing for inspiration. Huston’s film is an archetypal examination of greed’s insatiability. Humphrey Bogart starred alongside Walter Huston and Tim Holt as desperate men whose sudden gold strike tears them apart with violent suspicion and paranoia. However, no prospector or money-hungry tycoon ever depicted on film, not even Charles Foster Kane or Gordon Gekko, matches the intensity and savagery of Daniel Plainview.

The first of the two final scenes occur some years later, after Plainview has successfully established his empire and settled into a comfortable, unchecked solitude. With money and power to last his own lifetime, no longer is there a need for Plainview to pretend or suppress his narcissism. He remains nestled in his Greystone-esque estate, perpetually drunk. One evening, Plainview is visited by the now-grown H.W. (Russell Harvard), who has married Eli and Paul’s sister Mary (Colleen Foy). Through a sign interpreter, H.W. declares he cannot remain idle in the Plainview mansion any longer, and he plans to travel to Mexico with his wife and start his own oil company. Plainview responds, “You’re killing my image of you as my son.” He sees this as an unforgivable betrayal that establishes H.W. as competition, and competition is the enemy. The conversation descends into insults of H.W.’s deafness and illegitimate parentage. “I don’t even know who you are because you have none of me in you. You’re someone else’s. This anger, your maliciousness, backwards dealings with me. You’re an orphan from a basket in the middle of the desert, and I took you for no other reason than I needed a sweet face to buy land.” With no more need for H.W., and being too proud to admit he’s wounded, Plainview drops his façade and lashes out, “You’re not my son. You’re just a little piece of competition… You’re a bastard from a basket!” H.W. leaves without another word. Plainview is completely alone, festering, and shouting “Bastard from a basket!” to himself.

In the aftermath of this painful scene, Eli arrives to ask for help from Plainview, who has passed out drunk in his bowling alley. Eli is in financial woe. He asks for the $5,000 bonus on the Sunday land Plainview promised years ago and then tries to sell Plainview the Bandy lease. Finally, Plainview has Eli weak and desperate, and worse, he no longer needs Eli to preserve his interests. Eli admits he has lost everything and become a sinner. At this, Plainview agrees to buy the lease if Eli admits that he is a false prophet and god is nothing more than a superstition. Plainview seems to know that Eli believes this to be true and wants him to admit it, and through an ashamed smile, Eli does as he’s told, acting out a sermon in which he proclaims himself a false prophet and god a superstition. Then, at Eli’s frailest point, Plainview happily announces he has already slurped up all the oil in the valley thanks to drainage. Eli does not understand. “Drainage!” shouts Plainview. “If you have a milkshake, and I have a milkshake, and I have a straw… My straw reaches across the room and starts to drink your milkshake. I… drink… your… milkshake!” Eli sits ruined and pathetic. But that is not enough. Plainview claims he has already paid $10,000 to Paul, no doubt a lie to make things worse for Eli. “You’re not the chosen brother, Eli. It was Paul who was chosen,” Plainview mocks. “He found me and told me about your land… He’s the prophet. He’s the smart one… You’re just the afterbirth.” And then, after gleefully tormenting Eli, Plainview chases him around the bowling alley and beats him to death with a bowling pin. In the film’s final shot, he announces to his servant, “I’m finished” as though Eli’s body was a thing to be taken away.

In the aftermath of this painful scene, Eli arrives to ask for help from Plainview, who has passed out drunk in his bowling alley. Eli is in financial woe. He asks for the $5,000 bonus on the Sunday land Plainview promised years ago and then tries to sell Plainview the Bandy lease. Finally, Plainview has Eli weak and desperate, and worse, he no longer needs Eli to preserve his interests. Eli admits he has lost everything and become a sinner. At this, Plainview agrees to buy the lease if Eli admits that he is a false prophet and god is nothing more than a superstition. Plainview seems to know that Eli believes this to be true and wants him to admit it, and through an ashamed smile, Eli does as he’s told, acting out a sermon in which he proclaims himself a false prophet and god a superstition. Then, at Eli’s frailest point, Plainview happily announces he has already slurped up all the oil in the valley thanks to drainage. Eli does not understand. “Drainage!” shouts Plainview. “If you have a milkshake, and I have a milkshake, and I have a straw… My straw reaches across the room and starts to drink your milkshake. I… drink… your… milkshake!” Eli sits ruined and pathetic. But that is not enough. Plainview claims he has already paid $10,000 to Paul, no doubt a lie to make things worse for Eli. “You’re not the chosen brother, Eli. It was Paul who was chosen,” Plainview mocks. “He found me and told me about your land… He’s the prophet. He’s the smart one… You’re just the afterbirth.” And then, after gleefully tormenting Eli, Plainview chases him around the bowling alley and beats him to death with a bowling pin. In the film’s final shot, he announces to his servant, “I’m finished” as though Eli’s body was a thing to be taken away.

There Will Be Blood is first and foremost a character study of American ambition and primitive drives towards a singular, personally advantageous objective and, as suggested above, not without its comparisons to Citizen Kane (1941). Although, those searching for a Rosebud-esque device to answer unanswerable questions about Plainview should look elsewhere. Anderson’s film does not begin by asking, Who is Daniel Plainview? At least, not in the forthright way Citizen Kane presents its thesis. Told over the span of roughly thirty years, Plainview’s story shows him struggle and toil, (sometimes) suppress his violent indignation toward religion and other businessmen, until finally, the film finds him uncompromisingly satisfied, cruel, and malignant. Consider his scene with H.W. in the end, a revelation on par with Rosebud’s origin as a winter sled. Riches and freedom from moral obligation have freed Plainview to become the man he always was; he can finally pull back his lips to show the wolf’s teeth and embrace his animal nature in his rejection of the older H.W., or further, act out in his outrageous killing of Eli. Of course, a moral conundrum arises when unchecked strength turns into cruelty and oppression, even murder. In Nietzschean terms, Plainview goes beyond a philosophical handling of morality and instead descends into monstrosity. Even as Nietzsche condemned morality as a device of control and bastion for the weak, he wrote, “It goes without saying that I do not deny—unless I am a fool—that many actions called immoral ought to be avoided and resisted.” Plainview doesn’t have so temperate a perspective. Becoming free of his moral constraints to flame his narcissism is his ultimate goal through the film, and achieving wealth and power in America grants him uncommon freedom to bypass morality completely.

Anderson’s profound character study puts forth Plainview as a Western survivor, and therefore an archetypal American. Almost compulsively, the character must dominate the oil-abundant countryside for himself, creating a sense of security and accomplishment that surrounds him in his mansion, pampering his grotesquely portrayed and unbridled viciousness. Manifest Destiny served as an American metaphor to boost a nationalistic ego, wherein the conquest of the Western Frontier, and therefore Nature, is carried out through an almost Darwinian natural selection of the strongest Americans. Despite his horrific amorality, Plainview remains curiously admirable. After all, he has survived the harshest Nature through physical punishment and psychological cunning. He is what Nietzsche would call a “noble” person: “The noble person reveres the power in himself, and also his power over himself, his ability to speak and to be silent, to enjoy the practice of severity and harshness towards himself and to respect everything that is severe and harsh.” Through Plainview’s intelligence, directness, and unimpeded determination, he rises to wealth and power; though, at the same time, he is an unabashed misanthrope. There Will Be Blood finally reflects a larger portrait of America as a land of opportunity and opportunists, where any sense of moral regulation remains defeated in the face of rampant, capitalist self-interest. America does not exist out of some moral hierarchy; rather, it exists to fulfill a desire for opportunity and freely exploit privileges. Whether in the form of industrialists or the church, these institutions jealously seek their own self-interests under any number of pretenses.

Anderson’s profound character study puts forth Plainview as a Western survivor, and therefore an archetypal American. Almost compulsively, the character must dominate the oil-abundant countryside for himself, creating a sense of security and accomplishment that surrounds him in his mansion, pampering his grotesquely portrayed and unbridled viciousness. Manifest Destiny served as an American metaphor to boost a nationalistic ego, wherein the conquest of the Western Frontier, and therefore Nature, is carried out through an almost Darwinian natural selection of the strongest Americans. Despite his horrific amorality, Plainview remains curiously admirable. After all, he has survived the harshest Nature through physical punishment and psychological cunning. He is what Nietzsche would call a “noble” person: “The noble person reveres the power in himself, and also his power over himself, his ability to speak and to be silent, to enjoy the practice of severity and harshness towards himself and to respect everything that is severe and harsh.” Through Plainview’s intelligence, directness, and unimpeded determination, he rises to wealth and power; though, at the same time, he is an unabashed misanthrope. There Will Be Blood finally reflects a larger portrait of America as a land of opportunity and opportunists, where any sense of moral regulation remains defeated in the face of rampant, capitalist self-interest. America does not exist out of some moral hierarchy; rather, it exists to fulfill a desire for opportunity and freely exploit privileges. Whether in the form of industrialists or the church, these institutions jealously seek their own self-interests under any number of pretenses.

Paul Thomas Anderson has called There Will Be Blood his Western, and also his horror film; it also happens to be a decidedly philosophical portrait of America. Accomplishing one of cinema’s most fascinating, cruel characters, Daniel Day-Lewis’ incredible performance as Plainview personifies the American identity. Plainview is a man whose noble personal struggle for independence ends by blossoming into a post-industrial giant, and then reaching contented complacency with a monstrosity few movies have ever shown, or would have the guts to portray in such symbolic terms. In Plainview’s hands, Manifest Destiny becomes an individualistic enterprise to isolate himself from everything. He is perhaps cinema’s most barefaced, unrelenting extension of American narcissism, capitalism, and abuse of power—especially given that the method by which Plainview maintains his wealth and autonomy is the country’s historically recurrent motivation: oil. Plainview always gets away with it, makes his desired deal, deceives, and most importantly, wins. His unsympathetic uses of people, coupled with his deceptive expressions of emotion or piety (though brief and half-hearted), reflect a national hypocrisy existing in the so-called “morally right” American identity. Even worse, weasily, and pathetic remains Eli Sunday and his church, deluded by his plainly insincere notion of doing good, yet he remains even more corrupt than Plainview. Among the most powerful and singular filmic work in all of cinema, There Will Be Blood renders both institutions at their worst, revealing the monster of greed, money, and power that hides beneath their false and moralizing pretenses.

Bibliography:

Kaufmann, Walter ed. Basic Writings of Nietzsche. New York: Modern Library, 2000.

Murray, Terry. “There Will Be Blood.” Philosophy Now. Volume 74 (July/August 2009): 42-45.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. Translation by Douglas Smith, Oxford:. Oxford University Press, 2008

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Translation by Marion Faber, Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, 1998.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 1962.

Sperb, Jason. Blossoms and Blood: Postmodern Media Culture and the Films of Paul Thomas Anderson. University of Texas Press, 2014.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review