The Definitives

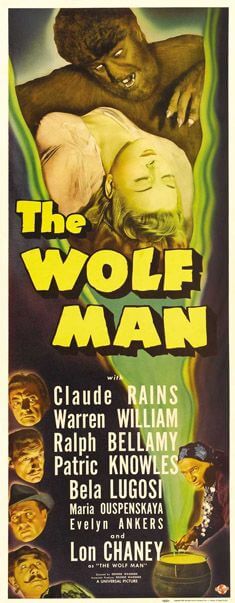

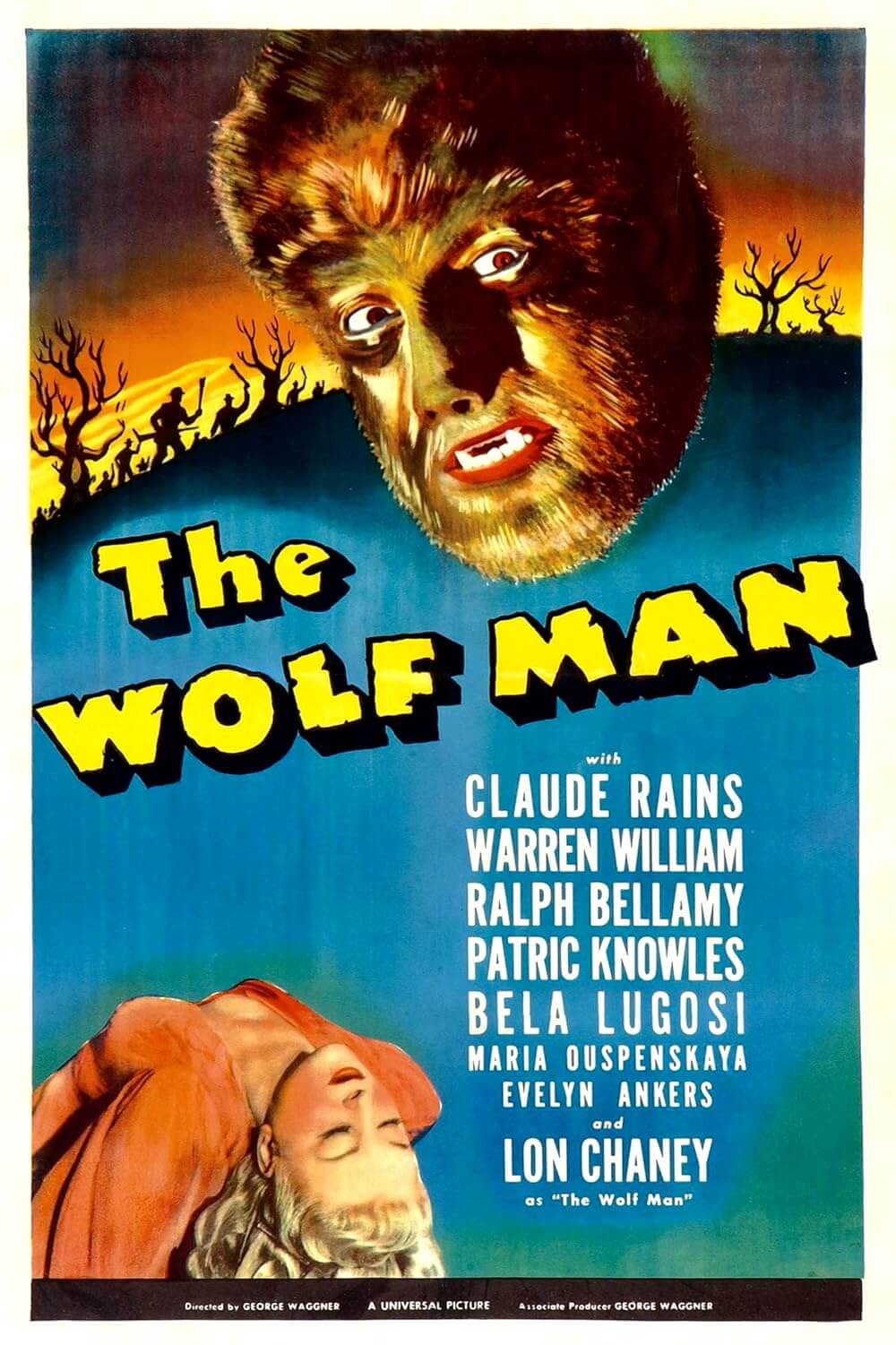

The Wolf Man (1941)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

How strange that the The Wolf Man, released by Universal Pictures in 1941, contains no monster at all. Certainly Lon Chaney Jr. endured hours in the makeup chair so that his character, Larry Talbot, would appear as a supernatural part man, part beast. But the story itself suggests that his character has been driven mad by tragedy and cultural hysteria, and that the transformation from man to monster occurs only in Talbot’s head. However legendary Chaney’s performance under the makeup may be, and however many sequels and offshoots may have followed in which the Wolf Man is treated as an authentic monster, this initial film is about madness as a symptom of duality, not some supernatural creature of the night. And from that perspective, the film proves ultimately more confronting, psychoanalytic, and undeniably more terrifying than an explanation rooted in the paranormal.

Universal was the premier studio for horror films in the Golden Age of Hollywood. As early as the silent era, they relied on the popularity of what were then considered B-grade horror pictures to attract audiences. Titles such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), Bride of Frankenstein (1935), and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) demonstrate that despite a common genre prejudice, horror films from the period were expertly crafted works filled with macabre themes and brooding atmosphere. Universal relied on these horror programmers to instill financial stability through franchises for iconic monsters, each spawning numerous profitable sequels. In doing so, the studio created unforgettable iconography that still influences the film industry and pop-culture today.

Amid Universal’s pantheon of movie monsters, the most human of them is the Wolf Man. Being someone who unwillingly falls victim to what he believes is a curse, he remains the only monster to regret his murderous nocturnal activities. Indeed, the sequels are almost exclusively dedicated to the Wolf Man seeking a way to end his cursed existence. Consider the remorselessness of his movie monster counterparts: Count Dracula served as an embodiment of pure evil in Bram Stoker’s hands, shameless about his bloodlust; Frankenstein’s monster is too reliant on bursts of raw emotion to feel regret over his victims; The Invisible Man was an insane scientist who murdered to demonstrate his power; The Mummy killed to service his own romantic desires; the Black Lagoon’s creature was little more than an animal. None but the Wolf Man reflected humanity so adeptly, capturing the duality behind the human monster.

Most cultures around the world have their own legend to explain the equal parts good and evil present in every person, la bête humaine lingering underneath the surface. According to these legends—everything from Bisclavret to Little Red Riding Hood—during particular times of the year or after specific events in one’s life, a person becomes susceptible to shape-shifting; they transform into an animal or turn into some horrible fiend. Some legends prove to be allegories about puberty or sexual drives, whereas others intend to clarify homicidal tendencies or serve as a scary story told to keep children in their beds at night. Tales like Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson manifest these legends into fiction, helping to solidify the image of the monster itself more than the foundational meaning behind it. Most such monsters have long since transcended their original intention through the startling imagery they employ, whereas the very nature of the Wolf Man cannot be separated from its symbolic and psychological implications.

Most cultures around the world have their own legend to explain the equal parts good and evil present in every person, la bête humaine lingering underneath the surface. According to these legends—everything from Bisclavret to Little Red Riding Hood—during particular times of the year or after specific events in one’s life, a person becomes susceptible to shape-shifting; they transform into an animal or turn into some horrible fiend. Some legends prove to be allegories about puberty or sexual drives, whereas others intend to clarify homicidal tendencies or serve as a scary story told to keep children in their beds at night. Tales like Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson manifest these legends into fiction, helping to solidify the image of the monster itself more than the foundational meaning behind it. Most such monsters have long since transcended their original intention through the startling imagery they employ, whereas the very nature of the Wolf Man cannot be separated from its symbolic and psychological implications.

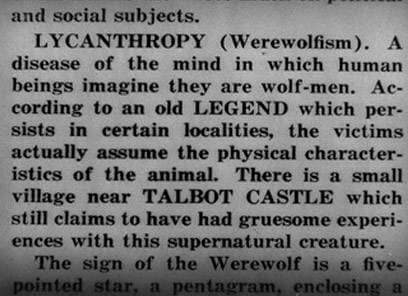

In the first scene of The Wolf Man, an encyclopedia page opens to an entry for “Lycanthropy (werewolfism)” which describes the condition as “A disease of the mind in which human beings believe they are wolf-men. According to an old LEGEND which persists in certain localities, the victims actually assume the physical characteristics of the animal.” Notice the capitalization of “legend” that was deliberately emphasized by screenwriter Curt Siodmak to accentuate how the ensuing story has no truth in the extraordinary. Instead, this is a story where people “believe” in the concept of a werewolf. This is not a story where the myth is proven real. Never is there a scene in the film where, in shocking realization, someone utters, “The legends were true!” The film portrays the Wolf Man creature with ambiguity; the audience sees what the protagonist sees, and because the protagonist believes himself a werewolf, the audience sees that too.

When the story begins, Larry Talbot returns home from America to Llanwelly, Wales, after the unfortunate death of his brother, to reunite with his father, Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains). Reconciling his estranged relationship with Sir John, Larry places his attention on a local woman, Gwen (Evelyn Ankers), ogling her through his father’s telescope (the “wolf” man indeed). While courting Gwen and growing accustomed to the backward ways of the small European village, Larry finds himself in a weakened state mentally. Emotionally vulnerable from a dead brother, therefore susceptible to the superstitions of the village, he repeatedly hears an old poem that haunts his unconscious mind: Even a man who is pure in heart, and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms, and the autumn moon is bright.

Larry has never heard of the werewolf legend from which the poem derives, though it interests him, enough even to purchase a cane that features a silver wolf head handle featuring a wolf inside a pentagram. Sir John explains that the werewolf tale is merely a story about “the dual personality in all of us,” but that every legend has its basis in fact. One evening Larry takes Gwen and her friend to have their fortunes read by a gypsy, Bela (Bela Lugosi). The friend goes first, while Larry convinces Gwen to take a walk in the ominously foggy woods. Screams suddenly echo through the forest, and Larry comes upon a wolf attacking Gwen’s friend. He stops the beast by striking it with his silver-handled cane, but the wolf bites him before it dies. When the police arrive to investigate, they find Bela’s corpse, his head pummeled by a blunt object. An old gypsy woman, Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya), later explains that Bela’s curse of werewolfism will now plague Larry, and that he will see the sign of the pentagram on his future victims. She gives Larry a pentagram talisman to wear around his neck for protection from the curse. Doubting his own sanity, Larry gives the necklace to Gwen.

Consider what the audience is shown in these scenes, and consider how the filmmakers slyly suggest that there never was an actual werewolf in The Wolf Man. When Larry first arrives to stop the wolf from killing Gwen’s friend, the audience sees a full-fledged wolf attacking her, as opposed to a man-beast. Larry begins wrestling with the animal, and there is a brief shot interspersed into Larry’s struggle with the wolf that clearly shows his opponent is a man. The next shot shows the wolf again; Larry throws it to the ground and, behind a tree, he beats the animal to death with his cane. Watch this scene closely, slow it down and observe frame by frame, and give your attention to the change from animal, to man, to animal. Perhaps this was the moment where the two images merged in Larry’s unconscious mind, so full with Llanwelly’s superstitions, lending him the material needed to fashion himself a lycanthropic alter-ego. Larry only sees either a full wolf or Bela in full human form; Bela never appears onscreen as a werewolf. Since Larry is “bitten”—a wound that is conspicuously healed by the next morning—he believes that the werewolfism has passed to him.

Consider what the audience is shown in these scenes, and consider how the filmmakers slyly suggest that there never was an actual werewolf in The Wolf Man. When Larry first arrives to stop the wolf from killing Gwen’s friend, the audience sees a full-fledged wolf attacking her, as opposed to a man-beast. Larry begins wrestling with the animal, and there is a brief shot interspersed into Larry’s struggle with the wolf that clearly shows his opponent is a man. The next shot shows the wolf again; Larry throws it to the ground and, behind a tree, he beats the animal to death with his cane. Watch this scene closely, slow it down and observe frame by frame, and give your attention to the change from animal, to man, to animal. Perhaps this was the moment where the two images merged in Larry’s unconscious mind, so full with Llanwelly’s superstitions, lending him the material needed to fashion himself a lycanthropic alter-ego. Larry only sees either a full wolf or Bela in full human form; Bela never appears onscreen as a werewolf. Since Larry is “bitten”—a wound that is conspicuously healed by the next morning—he believes that the werewolfism has passed to him.

From thereon out, Larry makes no audacious public appearances in his lycanthropic state. He appears as the Wolf Man only in one-on-one exchanges, and the victims never cry out “A werewolf!” or anything of the sort to confirm for the audience that a real transformation has taken place. His first kill, for example, occurs in a cemetery and the victim is a lone gravedigger. No witnesses. When Larry wakes up the next morning, he wipes away what he believes are animal tracks leading into his bedroom—but then later, when he tries to convince others of his curse, that evidence is gone. The townspeople suspect Larry is Bela’s killer; one woman even accuses him of looking at her “like a wild animal with murder in his eyes.” Surrounded by the village’s werewolf legend and being called an animal only reinforce Larry’s belief in his curse. But the authorities think a wild animal is killing villagers, and they set traps to ensnare it. That night, Larry’s leg is caught in the metal jaws of a foothold. Maleva the gypsy, a devout believer in werewolfism, frees him from the trap. When she does so, she sees a werewolf, but moments later two scouts hunting the beast see Larry.

What the film shows us is the power of superstition, in that those who believe in lycanthropy see Larry as a beast. The screenplay often reminds us, through Sir John or the story’s other werewolf skeptics, that “most anything can happen to a man in his own mind.” Through this reasoning, the superstitions of Llanwelly convince Larry of his own transformation. The quaint Euro-village has an undeniable history of belief in lycanthropy ingrained into their culture. When the power of that communal belief system finds its way to Larry, whose psyche is weak from displacement and tragedy, his subconscious fills in the blanks. He confesses his beliefs to Sir John, and he convinces his father to take the cane with a handle of silver—which he has been told is a werewolf’s only weakness—when a posse of villagers set out to hunt for the beast. Despite being tied down by Sir John at his own request, Larry escapes and attacks Gwen in the forest. Sir John comes to rescue her and stops his son, beating Larry to death with the silver cane. Looking upon the body, Sir John watches as the murderous creature fades away into just a man, suggesting that he now sees the monster inside every man, even a loved one, and thus he discovers the origin of the werewolf legend. But to be sure, it is only a legend.

Lon Chaney Jr. would play the Wolf Man role five times, next in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) and finally in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), though none of the sequels or spinoffs treated the character with the same ambiguity toward his curse. By the time the sequels came to pass, audiences had long since missed the point, and Universal was more than content with giving ticket buyers a bona fide monster. In fact, the studio went to great lengths to secure the Wolf Man for sequels; they resurrected the character from the dead, and later on simply omitted that he had ever died in the 1941 original. Following in the footsteps of his father and silent film star Lon Chaney Sr., the noted “Man of 1,000 Faces” who played everyone from Quasimodo to the Phantom of the Opera, Chaney Jr. was forever associated with his role as the Wolf Man.

Lon Chaney Jr. would play the Wolf Man role five times, next in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) and finally in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), though none of the sequels or spinoffs treated the character with the same ambiguity toward his curse. By the time the sequels came to pass, audiences had long since missed the point, and Universal was more than content with giving ticket buyers a bona fide monster. In fact, the studio went to great lengths to secure the Wolf Man for sequels; they resurrected the character from the dead, and later on simply omitted that he had ever died in the 1941 original. Following in the footsteps of his father and silent film star Lon Chaney Sr., the noted “Man of 1,000 Faces” who played everyone from Quasimodo to the Phantom of the Opera, Chaney Jr. was forever associated with his role as the Wolf Man.

To accomplish the actor’s onscreen metamorphosis, special effects artist Jack Pierce used a combination of rubber framework, false teeth, and wigs to bring the werewolf to life. Pierce started in Hollywood as an assistant makeup artist on The Man Who Laughed (1928) and made a name for himself with the makeup designs of Universal’s Frankenstein monster, the Bride of Frankenstein, and the Mummy. Pierce also designed the Wolf Man look for actor Henry Hull on the set of Werewolf of London (1935), though at the time his makeup schema was rejected. Originally the studio wanted a more animal-like creature in the film, though the censors refused to allow the monster to appear too much like an actual wolf; they preferred him in humanoid form. The eventual design evokes the accelerated facial hair grown of hypertrichosis, then popularized by Fyodor Yevtishchev, Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy from P.T. Barnum’s circus sideshow. Pierce avoided more realistic Canidae features so the Wolf Man character would resemble an anthropomorphized animal, allowing Chaney to make versatile facial movements under his makeup. Even so, Pierce’s makeup left Chaney under a mound of yak hair and uncomfortable prosthetics, including false fangs that gave the monster a nasty underbite.

For the changeover from man to monster, director George Waggner used dissolves that fade in and out of progressive steps in the werewolf transformation via time lapse photography. Pierce would apply a stage of Chaney’s makeup, a few seconds of footage would be shot, the next stage would be applied, another few seconds of footage shot, and so on for hours and hours until the entire transformation was captured. The procedure was an arduous one, but it was copied for years until makeup artists like Rick Baker (An American Werewolf in London, The Howling) developed animatronics that would lend the appearance of a transformation without the painstaking process of dissolves. For his contributions to the studio’s status as Hollywood’s top monster factory, Pierce was ultimately sacked from Universal for refusing to progress his ideas and accept new, cheaper, more efficient ways of doing makeup designs—he was still dedicated to rubber when everyone else began using more cost-effective foam molds. And yet, his designs continue to inspire filmmakers today, his unwillingness to evolve in the industry notwithstanding.

As an unfortunate side-effect of Pierce’s superb makeup designs, however, the originality of screenwriter Curt Siodmak fails to receive its due credit. Unlike the stories of Dracula and Frankenstein, the story for The Wolf Man has no source in classic literature. Inspired by, but not dependent on an initial script draft by Robert Florey, Siodmak invented the modern concept of the werewolf in the same sense that Bram Stoker invented the vampire, imbuing the monster with imagined attributes and weaknesses bound to the lore within the film, but which today are incorrectly viewed as age-old legends. For example, from vampire mythos, Siodmak conceived the notion of the werewolf’s bite spreading the curse to its victim. A German-Jew who fled his native country as Adolf Hitler came to power, Siodmak used the pentagram star as a parallel for Nazis labeling Jews as their intended victims, just as Talbot sees the pentagram appear on his future prey. From traditional folklore, Siodmak used the idea that vampires were susceptible to silver and reapplied it here; today, pop-culture has almost no knowledge of the original myth, only Siodmak’s suggestion that silver is a werewolf’s Achilles Heel.

As an unfortunate side-effect of Pierce’s superb makeup designs, however, the originality of screenwriter Curt Siodmak fails to receive its due credit. Unlike the stories of Dracula and Frankenstein, the story for The Wolf Man has no source in classic literature. Inspired by, but not dependent on an initial script draft by Robert Florey, Siodmak invented the modern concept of the werewolf in the same sense that Bram Stoker invented the vampire, imbuing the monster with imagined attributes and weaknesses bound to the lore within the film, but which today are incorrectly viewed as age-old legends. For example, from vampire mythos, Siodmak conceived the notion of the werewolf’s bite spreading the curse to its victim. A German-Jew who fled his native country as Adolf Hitler came to power, Siodmak used the pentagram star as a parallel for Nazis labeling Jews as their intended victims, just as Talbot sees the pentagram appear on his future prey. From traditional folklore, Siodmak used the idea that vampires were susceptible to silver and reapplied it here; today, pop-culture has almost no knowledge of the original myth, only Siodmak’s suggestion that silver is a werewolf’s Achilles Heel.

Siodmak sought to instill his narrative with the potency of Greek mythology, telling a tale of a great man cursed and fated to be destroyed by his inner demons, as opposed to the manifestation of a monster “legend” made flesh. Using heavy symbols such as the moon, silver, and transformations from man to beast, Siodmak accomplished his objective almost too well. Generations of moviegoers were fooled into believing that his werewolf poem, which he repeats several times within the film for added effect, was real. The strength of the story’s imagery and the power of the faux legend at the center of the film would not only influence Larry Talbot, but it would cause audiences to remember the stark iconography and the memorable lines of Siodmak’s scenario even more than they would see The Wolf Man as a parable for the horrible potential stirring inside all human beings.

Essential for devising the modern concept of the werewolf, from which nearly every subsequent werewolf film has drawn inspiration, the film uses the guise of a horror yarn to consider the duality of human beings. To be sure, Siodmak wanted an upfront discussion about the film’s theme of duality, but the studio wanted another franchise for their successful string of horror characters. Universal demanded that any question of uncertainty about the reality of the monster be edited out of the final film. But even with their cutting, The Wolf Man remains not a mere monster movie; rather, it’s a film about la bête humaine. Siodmak’s discussion is too deeply rooted in the material to wipe it out, even with the cleverest editing. The signs are everywhere, whether they are buried in the subtext or emergent through careful analysis of what the audience is not shown. Along with its complete invention of the werewolf myth, that the film is not about werewolves at all remains The Wolf Man’s little secret, waiting to be rediscovered.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review