The Definitives

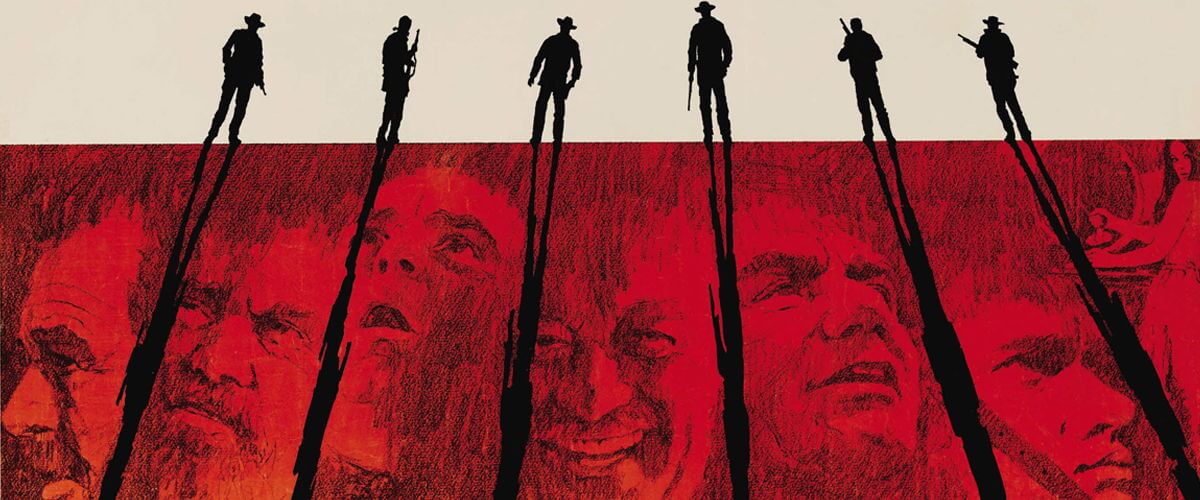

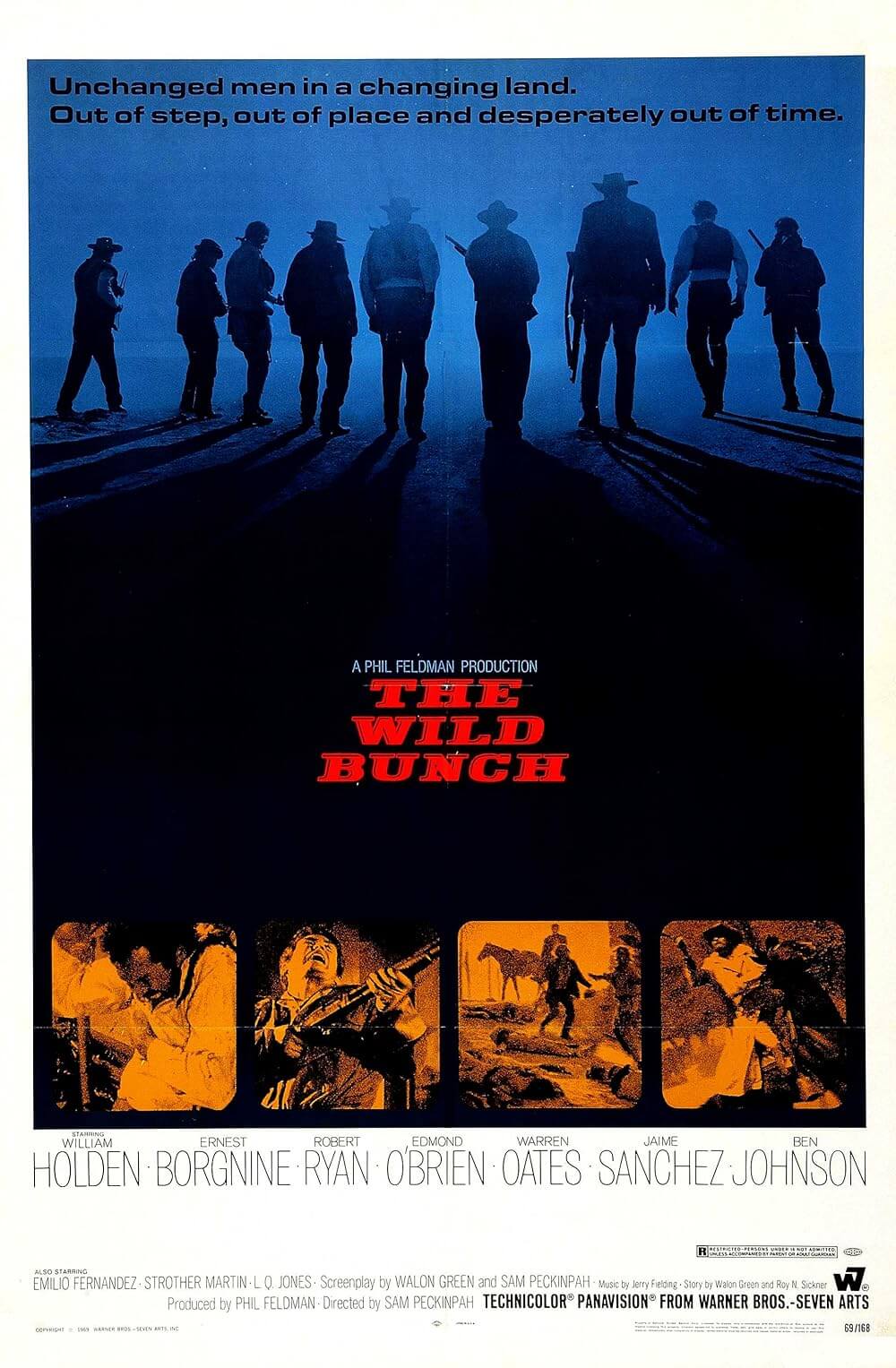

The Wild Bunch (1969)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Demystifying the traditional Western through raw, unglamorous violence, The Wild Bunch exploded onto the screen in 1969 and altered the face of the genre, and filmmaking, forever. Sam Peckinpah set aside what other Western directors had done—the myth-making embrace of John Ford, the pure style of Sergio Leone, and the humanist complexity of Anthony Mann—for something entirely new. With the film, he earned his nickname “Bloody Sam” for his depiction of onscreen bloodshed, but he released a motion picture that remains far more than the revolution of violence, a revolution which would achieve full insurgency in the subsequent years when film censorship and Hollywood studios exercised unprecedented clemency toward screen violence. The picture may even have killed the romanticism of the Old West in cinema and brought about, albeit unintentionally, the genre’s gradual downfall. Filled with tragic characters defined by their sadness and regret, Peckinpah’s film confronts its audience with an honest representation of Western outlaws and the violence that surrounded them. His characters are rugged men in unforgiving situations, bound to each other by a code of honor not even they follow, all of them far removed from the admirable cowboy heroes to which moviegoers had grown accustomed. Peckinpah recognizes the myth of the American West and tears it down, amplifying the gritty nature of this history until the myth has been forever shattered. With The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah, ever the iconoclast, may as well have splattered a bucket of red paint all over the works of Albert Bierstadt.

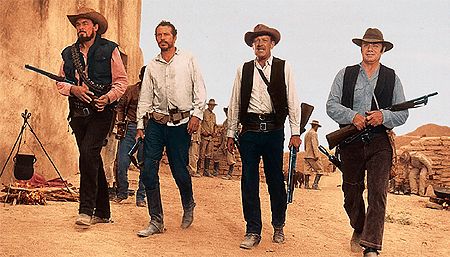

When they rob a railroad office in Starbuck on the Texas-Mexico border, Pike Bishop’s (William Holden) gang is confronted by a posse of bounty hunters, led by Pike’s former partner Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan)—the posse hired by the railroad industrialist Harrigan (Albert Dekker) to take the Bunch down. After an ambush and bloody shootout, the Bunch flees into Mexico, tailed by Thornton’s posse, and discovers the score was a setup; their loot is nothing more than sacks of iron washers. Once they arrive in the Mexican town of Agua Verde, they strike a deal with its overseer, General Mapache (Emilio Fernández), an independent Mexican warlord fighting on the side of Presedente de la Huerta, to steal rifles and ammunition from a U.S. Army transport. However, one of the Bunch, Angel (Jaime Sánchez), sympathizes with Pancho Villa and appeals to Pike to “lose” just one case of rifles and a single case of ammunition. Pike concedes, though the eventual robbery is another setup where the Bunch is confronted by Thornton. After leading Thornton into a trap by detonating a bridge under his posse’s feet and dropping them into the Rio Grande, the Bunch makes it back to Mexico with their loot of guns and bullets. But Mapache finds out about Angel’s people getting one of the cases; so he detains Angel and happily pays the Bunch their gold. Once their transaction with Mapache is complete, Pike and the others realize they have no choice but to head back to Agua Verde, if only to seek shelter from Thornton. Once there, they see Mapache torturing Angel, pulling his nearly dead body behind an automobile. Pike and the Bunch resolve to rescue Angel, the four of them facing off against more than 250 Mexican soldiers in a bloodbath from which no one—not Angel, not Pike, not his Bunch, and certainly not Mapache—walks away.

Peckinpah’s equal measures of attraction and revulsion toward violence defined his films, particularly his work in the late-sixties and early seventies, such as Straw Dogs (1971). Peckinpah once said, “The whole underside of our society has always been violence and still is. Churches, laws—everybody seems to think that man is a noble savage. But he’s only an animal, a meat-eating, talking animal. Recognize it. He also has grace, and love, and beauty. But don’t say to me we’re not violent. Because we are. It’s one of the greatest brainwashes of all times to say we’re not.” With this in mind, Peckinpah set out to create a film that dispels what legend has taught us about the American West, and the horrifically violent aspect of American identity that such legends often refuse to acknowledge. In a 1999 article about Peckinpah for The New Yorker called The Wild Man, critic Pauline Kael wrote, “I remember his talking to me, when he was planning The Wild Bunch, saying that he was going to make a picture so ferocious that it would rub people’s noses in the ugliness of violence. They would never want to see anything violent again. But when the picture came out and there were insensitive people who cheered the bloodshed, he seemed delighted—he acted vindicated…” Peckinpah made films that tested his audiences’ tolerances toward violence and how the violence in his films acted as a reflective device for their own conflicting human-animal nature. Whether the viewer interprets the violence as thrilling or repulsive, either response is correct. But to fully understand the impact of and purpose behind The Wild Bunch, one must first know its director and realize what vision he brought to the picture.

Peckinpah’s equal measures of attraction and revulsion toward violence defined his films, particularly his work in the late-sixties and early seventies, such as Straw Dogs (1971). Peckinpah once said, “The whole underside of our society has always been violence and still is. Churches, laws—everybody seems to think that man is a noble savage. But he’s only an animal, a meat-eating, talking animal. Recognize it. He also has grace, and love, and beauty. But don’t say to me we’re not violent. Because we are. It’s one of the greatest brainwashes of all times to say we’re not.” With this in mind, Peckinpah set out to create a film that dispels what legend has taught us about the American West, and the horrifically violent aspect of American identity that such legends often refuse to acknowledge. In a 1999 article about Peckinpah for The New Yorker called The Wild Man, critic Pauline Kael wrote, “I remember his talking to me, when he was planning The Wild Bunch, saying that he was going to make a picture so ferocious that it would rub people’s noses in the ugliness of violence. They would never want to see anything violent again. But when the picture came out and there were insensitive people who cheered the bloodshed, he seemed delighted—he acted vindicated…” Peckinpah made films that tested his audiences’ tolerances toward violence and how the violence in his films acted as a reflective device for their own conflicting human-animal nature. Whether the viewer interprets the violence as thrilling or repulsive, either response is correct. But to fully understand the impact of and purpose behind The Wild Bunch, one must first know its director and realize what vision he brought to the picture.

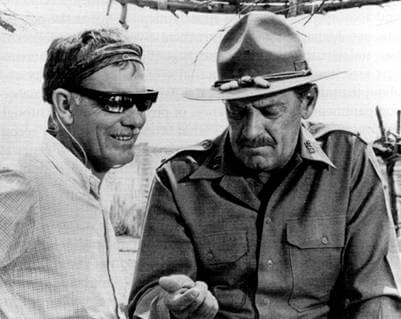

Sam Peckinpah (1925-1984) was a troubled man, raised as a boy on a rugged ranch in Fresno, California owned by his grandfather, the cowboy, Superior Court Judge, and District Attorney named Denver Church. After he served in World War II and received his graduate degree in drama, Peckinpah apprenticed under director Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1956) and became a writer on the television shows Gunsmoke and The Rifleman. Soon he moved to his own features and continued in the Western genre, establishing a name for himself with his second directorial effort, Ride the High Country (1962), starring genre icons Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott. At the same time, he developed a reputation. He drank hard, and later used drugs and bedded whores in seedy Mexico towns. During the production of Major Dundee (1965), he showed up on the set drunk and directed under the influence, slung insults at his cast and crew, and almost came to blows with star Charlton Heston. His behavior became so unruly that the production was taken away from him by the studio during the editing process. When the film bombed at the box-office, Peckinpah’s standing in Hollywood suffered a harsh blow. Even worse, after just four days of shooting he was fired from his next project, The Cincinnati Kid (1965), and Peckinpah’s banishment from Hollywood was all but absolute. Only after he completed the acclaimed hour-long television adaptation of Katherine Anne Porter’s dramatic novel Noon Wine did his reputation begin to heal. Still, by the time Warner Bros. producers Kenneth Hyman and Phil Feldman brought Walon Green’s screenplay of The Wild Bunch to Peckinpah, the ousted director had been out of real work for years.

Not only did the prospect of again directing a feature film Western appeal to Peckinpah, but the material itself inspired him like no other project had done before. In many ways, The Wild Bunch would be his chance to achieve the types of thematic motifs he had tried and in some respect failed to accomplish on his earlier work at that point. The screen story by Green and Roy N. Sickner borrowed much from legendary outlaw Butch Cassidy’s history, the title itself derived from the name of Cassidy’s gang, called the Wild Bunch. Over at 20th Century Fox, William Goldman’s screenplay Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had gone into development and gathered the likes of Paul Newman and Robert Redford to star for director George Roy Hill. Hyman and Feldman wanted to beat Fox’s project to theaters and thought Peckinpah was perfect for the job. And while Goldman’s screenplay celebrated the time-honored and romantic Western notion of noble, even heroic outlaw, Peckinpah’s film would explore what such outlaws were really like. What kinds of men slaughter innocents for a railroad robbery payday and then laugh about it when the loot turns out to be iron washers? What kinds of men sacrifice themselves for a member of their gang? After six months of expanding and rewriting Green’s script on his own, Peckinpah knew he had something special. Green had laid the foundation but Peckinpah added more and more in his rewrites, layering the characters with backstories, deep-rooted motivations, and a sense of Shakespearian tragedy.

Not only did the prospect of again directing a feature film Western appeal to Peckinpah, but the material itself inspired him like no other project had done before. In many ways, The Wild Bunch would be his chance to achieve the types of thematic motifs he had tried and in some respect failed to accomplish on his earlier work at that point. The screen story by Green and Roy N. Sickner borrowed much from legendary outlaw Butch Cassidy’s history, the title itself derived from the name of Cassidy’s gang, called the Wild Bunch. Over at 20th Century Fox, William Goldman’s screenplay Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had gone into development and gathered the likes of Paul Newman and Robert Redford to star for director George Roy Hill. Hyman and Feldman wanted to beat Fox’s project to theaters and thought Peckinpah was perfect for the job. And while Goldman’s screenplay celebrated the time-honored and romantic Western notion of noble, even heroic outlaw, Peckinpah’s film would explore what such outlaws were really like. What kinds of men slaughter innocents for a railroad robbery payday and then laugh about it when the loot turns out to be iron washers? What kinds of men sacrifice themselves for a member of their gang? After six months of expanding and rewriting Green’s script on his own, Peckinpah knew he had something special. Green had laid the foundation but Peckinpah added more and more in his rewrites, layering the characters with backstories, deep-rooted motivations, and a sense of Shakespearian tragedy.

Peckinpah transformed unlovable, outwardly vile characters and in turn makes us care about such les bêtes humaines, something that might have been otherwise impossible without his affable cast. When casting the picture, both Peckinpah and Hyman (who had produced The Dirty Dozen, 1967)wanted Lee Marvin for Pike Bishop, but the star passed to lighten his hard-boiled image with the musical Paint Your Wagon (1969). In the previous decade, William Holden had been dubbed Hollywood’s “Golden Boy” (after starring in 1939’s Golden Boy), but the good-looking actor had since grown weathered, his figure and face worn and melancholy from years of hard drinking. He was the perfect choice to play Pike. Hyman pushed for other alumni from The Dirty Dozen: the tall, underrated Robert Ryan was now graying and looked like the soul-depleted Thornton; the rotund, cheery-yet-intimidating Ernest Borgnine would be Pike’s loyal right hand, Dutch. For the role of Freddie Sykes—a role that ten years earlier would have been perfect for an old coot like Walter Brennan—they chose Edmond O’Brien, whose cataracts and ill health made him appear decades beyond his age of 53. Other Western regulars Ben Johnson and Warren Oates were cast as the Gorch brothers, Tector and Lyle. Newcomer Jaime Sánchez rounded out the Bunch as Angel. For Mapache, there was never anyone else for Peckinpah than Mexican filmmaker and actor Emilio Fernández, who would also co-star in the director’s 1972 film Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia alongside Oates.

Peckinpah’s script had reinvigorated the hard-living filmmaker, as well as the studio’s confidence in him. 75 days of shooting were scheduled at a budget of $3.4 million. Despite the horror stories associated with the Mexican production of Major Dundee, Peckinpah resolved to once again shoot in Mexico. But rather than having to trek across hundreds of miles of harsh terrain from one location to the next as he had before, the film’s desert, river, mountain, and forest locations were all found within a few miles of two towns, Parras and Torreon. Mapache’s stronghold at Agua Verde was set at a nearby abandoned winery. Parras would stand in for the Mexican border town Starbuck. The locations proved so perfect that Peckinpah, a largely improvisational director, began to outline scenes in advance. Parras buildings were lined with huge breakaway glass windows that would be blown out during the opening shootout. By the end of the first day, the FX company had run out of blank ammo rounds and fake blood. By the end of the entire shoot some 81 days and $6.4 million dollars later, the production used 239 guns and over 90,000 blank rounds—more than what was used in the Mexican revolution, according to the ever-exaggerating publicity department at Warner Bros. Peckinpah wanted The Wild Bunch to be something significant—to reflect the obscenity of violence seen every day in reports from the Vietnam War; at the same time, he wanted to outdo the shocking depiction of violence in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Peckinpah’s script had reinvigorated the hard-living filmmaker, as well as the studio’s confidence in him. 75 days of shooting were scheduled at a budget of $3.4 million. Despite the horror stories associated with the Mexican production of Major Dundee, Peckinpah resolved to once again shoot in Mexico. But rather than having to trek across hundreds of miles of harsh terrain from one location to the next as he had before, the film’s desert, river, mountain, and forest locations were all found within a few miles of two towns, Parras and Torreon. Mapache’s stronghold at Agua Verde was set at a nearby abandoned winery. Parras would stand in for the Mexican border town Starbuck. The locations proved so perfect that Peckinpah, a largely improvisational director, began to outline scenes in advance. Parras buildings were lined with huge breakaway glass windows that would be blown out during the opening shootout. By the end of the first day, the FX company had run out of blank ammo rounds and fake blood. By the end of the entire shoot some 81 days and $6.4 million dollars later, the production used 239 guns and over 90,000 blank rounds—more than what was used in the Mexican revolution, according to the ever-exaggerating publicity department at Warner Bros. Peckinpah wanted The Wild Bunch to be something significant—to reflect the obscenity of violence seen every day in reports from the Vietnam War; at the same time, he wanted to outdo the shocking depiction of violence in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

As suggested, Peckinpah’s style of shooting did not involve intensive preplanning. He was a master of on-the-spot orchestration. He woke up every day at four in the morning and looked over the day’s scenes. Cinematographer Lucien Ballard rode with Peckinpah to the set and discussed how the day’s scenes should look. Armed with six cameras in all, he stationed them at various angles and directed a scene with the cameras rolling, allowing the sequence to progress on its own, almost naturally, while the cameras captured everything. His approach required a genius nothing like that of filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa or Alfred Hitchcock, who preplanned everything on storyboards. Peckinpah would assemble elements of a scene one by one until, for him, it was complete. For example, when the Bunch leaves Angel’s village after they recuperate from being chased across the border by Thornton, Peckinpah kept adding elements until their majestic departure was just right. What was originally just the Bunch riding out of the village becomes a grand farewell, each detail added by Peckinpah on the spot: The old man waving goodbye, a girl who brings Dutch a flower, a woman who brings Tector his hat, smoke hovering through the scene, and the aching Mexican ballad to send them off. Another scene at the end, when Pike summons his Bunch to march to their death into the bloodbath, was similarly assembled on a whim, Peckinpah adding components until it became perhaps the film’s most iconic scene.

But not every sequence could be improvised on-set. The finale’s bloodbath sequence alone took days of planning, and Peckinpah even drew thumbnail sketches on scraps of paper and the script to devise the sequence beforehand. The director sat in the old abandoned winery for hours upon hours until he slowly visualized it with the help of his cast and crew. When the sequence was finally completed, it took twelve days to shoot, 10,000 squibs, and 350 Mexican soldier costumes (each having to be repeatedly repaired to accommodate the multiple takes). By this time, Peckinpah was well over budget, but Warner Bros. executives had been so pleased with the early footage that they agreed to give the director whatever he needed to complete the film. The last major scene filmed was the bridge explosion, the stunning sequence where Thornton and his men have trailed behind Pike’s Bunch. They fire off rounds from a river bridge, which has been rigged to blow. All at once, the bridge blows and it drops from under them and everyone—the bounty hunters and their horses—fall into the water. The sequence employed no models or miniatures, just padded stuntmen who wore helmets under their cowboy hats to protect them from the horses which frantically swam to shore. One of the stuntmen thanked Peckinpah for designing the most grandiose stunt he’d ever taken part in; another cursed the director and walked off the set.

But not every sequence could be improvised on-set. The finale’s bloodbath sequence alone took days of planning, and Peckinpah even drew thumbnail sketches on scraps of paper and the script to devise the sequence beforehand. The director sat in the old abandoned winery for hours upon hours until he slowly visualized it with the help of his cast and crew. When the sequence was finally completed, it took twelve days to shoot, 10,000 squibs, and 350 Mexican soldier costumes (each having to be repeatedly repaired to accommodate the multiple takes). By this time, Peckinpah was well over budget, but Warner Bros. executives had been so pleased with the early footage that they agreed to give the director whatever he needed to complete the film. The last major scene filmed was the bridge explosion, the stunning sequence where Thornton and his men have trailed behind Pike’s Bunch. They fire off rounds from a river bridge, which has been rigged to blow. All at once, the bridge blows and it drops from under them and everyone—the bounty hunters and their horses—fall into the water. The sequence employed no models or miniatures, just padded stuntmen who wore helmets under their cowboy hats to protect them from the horses which frantically swam to shore. One of the stuntmen thanked Peckinpah for designing the most grandiose stunt he’d ever taken part in; another cursed the director and walked off the set.

For the six months of editing, Peckinpah hand-selected editor Lou Lombardo, who wanted to test a unique style whereby each of the director’s cameras would be set to a unique film speed (24, 30, 48, 60, 90, and 120 frames-per-second). Lombardo’s scenes show slow-motion death intercut with shooters at normal speed, creating an effect that heralds the poetry and primitive nature of violence. Consider the sequence during the opening ambush in Starbuck, where a bounty hunter takes a bullet and slowly topples from his rooftop perch. Lombardo cuts back-and-forth between the bounty hunter’s slow-motion fall and the Bunch’s frenzied escape at normal speeds. The effect, used on the film’s major shootouts, becomes the film’s key metaphor for the effect of violence on the viewer—we are repulsed by violence yet oddly drawn to it. There’s dramatic poetry in the slow-motion image of a man falling to his death, as so often found in the regal use of the device in Kurosawa’s cinema, a great influence on Peckinpah. But we cannot help but feel an aversion to the chaotic violence found in Lombardo’s fast cutting between shots of Pike’s men scrambling to get away, bullets flying into innocents, horses trampling bystanders, and the railroad’s bounty hunters unleashing countless rounds. Death is everywhere, and there’s no telling who’s who. It’s exciting but ugly, unfunny and thrilling. Like the film itself. Lombardo’s cutting style was revolutionary and changed the face of cinema forevermore, though he admitted that Peckinpah’s obsessive attention to detail—the director often told Lombardo to add or subtract just one frame to perfect a shot—taught him much. Most films of the era had an average of 600 cuts, but Lombardo’s work on The Wild Bunch had 3,642. The director was equally attuned to sound FX and required that every gun in the film have unique sounds, whereas most Warner Bros. productions had used the same gunshot sounds since the 1930s.

Before shooting, but after pre-production had already begun, Peckinpah was talking to Emilio Fernández about the script, and Fernández remarked that its characters reminded him of his childhood experiences torturing scorpions on an ant hill. Inspired, Peckinpah immediately leaped up and called for ants and scorpions on the set. The image and metaphor hinted at by Fernández would set the themes of the entire film. It would be the audience’s entry point into the picture, and a foreshadowing device not only for the ambush at Starbuck, but the bloodbath of the Agua Verde finale. As Pike and his Bunch ride into Starbuck, they stop and observe children sitting around a makeshift arena of sticks, watching and laughing as inside they poke at scorpions, which have been dropped into a festering swarm of hungry ants. This is the cruel world in which both we and the Wild Bunch live—a world where children are all but inborn with a streak of brutality and pitilessness. A world where abhorrent violence becomes a form of entertainment. Peckinpah’s use of this image in The Wild Bunch reflects not only the characters and their fates but the audience as we watch with equal measures of exhilaration and aversion to the violence onscreen. That dynamic and commentary on violence is a recurring theme in Peckinpah’s most celebrated films from The Wild Bunch to Straw Dogs to Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, and often a divisive factor for his audience.

Before shooting, but after pre-production had already begun, Peckinpah was talking to Emilio Fernández about the script, and Fernández remarked that its characters reminded him of his childhood experiences torturing scorpions on an ant hill. Inspired, Peckinpah immediately leaped up and called for ants and scorpions on the set. The image and metaphor hinted at by Fernández would set the themes of the entire film. It would be the audience’s entry point into the picture, and a foreshadowing device not only for the ambush at Starbuck, but the bloodbath of the Agua Verde finale. As Pike and his Bunch ride into Starbuck, they stop and observe children sitting around a makeshift arena of sticks, watching and laughing as inside they poke at scorpions, which have been dropped into a festering swarm of hungry ants. This is the cruel world in which both we and the Wild Bunch live—a world where children are all but inborn with a streak of brutality and pitilessness. A world where abhorrent violence becomes a form of entertainment. Peckinpah’s use of this image in The Wild Bunch reflects not only the characters and their fates but the audience as we watch with equal measures of exhilaration and aversion to the violence onscreen. That dynamic and commentary on violence is a recurring theme in Peckinpah’s most celebrated films from The Wild Bunch to Straw Dogs to Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, and often a divisive factor for his audience.

Indeed, the test screenings for The Wild Bunch were less enthusiastic than Warner Bros. had hoped. Outraged viewers—the ones who hadn’t already walked out—filled out their comment cards with furious scribbling. Only a small percentage marked that they thought the film was great. Had it been three decades earlier or much later, scores like this would have resulted in Warner Bros. dumping the release without much promotion. But in the sixties, films like Bonnie and Clyde that pushed the limits of violence and sex in cinema achieved a unique kind of popularity. Audiences wanted to be outraged. This was true to such an extent that Warner Bros. welcomed the MPAA’s eventual R-rating, as the more wholesome G or M ratings would have suggested The Wild Bunch was just another safe Western. Upon its opening in wide release in the southern states and limited release in New York and Los Angeles, critics claimed Peckinpah had found a confronting allegory for Vietnam, although a few mentioned the film’s running time of 145 minutes was long. Peckinpah agreed to the studio’s eventual demands and trimmed the runtime, removing “slower” character building scenes and histories. But producer Phil Feldman later took it upon himself to remove an additional 10 minutes of footage when he received additional complaints from theater owners that the film was overlong. Feldman removed even more backstories and scenes of the Mexican revolution, these without Peckinpah’s consent. After a few weeks in distribution, the picture was out in various lengths and cuts; none were Peckinpah’s original cut, and none featured the crucial flashbacks and dramatic touches the director so carefully incorporated.

Although Warner Bros. was successful and beat Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to the theaters, the controversy and uncertainty surrounding The Wild Bunch’s release led to both audiences and critics greeting the film with aversion and confusion, and only the occasional rave. Still, that confusion made it one of the most talked and written about films of the year. By the following year, the more commercially viable, audience-friendly, M-rated release Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid not only beat out The Wild Bunch at the box-office, it won in the two Academy Award categories for which Peckinpah’s film was nominated: Jerry Fielding lost to Burt Bacharach for Best Score; Peckinpah, Green, and Sickner lost to Goldman for Best Screenplay. Of the other rebellious films released in the Sixties, few had been as divisive, bold, or challenging as The Wild Bunch. Audiences could get behind the fun-loving stoners in Easy Rider, the poignancy behind the drama of Midnight Cowboy, or a counterculture comedy like Alice’s Restaurant. The Wild Bunch had no such appeal. And not until 1993 could audiences reassess Peckinpah’s full, restored, uncut masterpiece when Warner Bros. rereleased the “Director’s Cut” into a few art house and revival theaters. However, despite the 1969 version receiving an R-rating, the MPAA demanded the picture be sacked with a new rating of NC-17, which prevented the studio from launching a wider distribution campaign. Regardless, in the years following its release, the Western declined in popularity, perhaps because of films like The Wild Bunch, whereby audiences began to recognize that the romanticism of the American West was an illusion and that, in fact, the era of Manifest Destiny was ridden with lawlessness, savagery, and genocide. Some might consider it progress that moviegoers no longer wanted to live in that illusion.

Although Warner Bros. was successful and beat Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to the theaters, the controversy and uncertainty surrounding The Wild Bunch’s release led to both audiences and critics greeting the film with aversion and confusion, and only the occasional rave. Still, that confusion made it one of the most talked and written about films of the year. By the following year, the more commercially viable, audience-friendly, M-rated release Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid not only beat out The Wild Bunch at the box-office, it won in the two Academy Award categories for which Peckinpah’s film was nominated: Jerry Fielding lost to Burt Bacharach for Best Score; Peckinpah, Green, and Sickner lost to Goldman for Best Screenplay. Of the other rebellious films released in the Sixties, few had been as divisive, bold, or challenging as The Wild Bunch. Audiences could get behind the fun-loving stoners in Easy Rider, the poignancy behind the drama of Midnight Cowboy, or a counterculture comedy like Alice’s Restaurant. The Wild Bunch had no such appeal. And not until 1993 could audiences reassess Peckinpah’s full, restored, uncut masterpiece when Warner Bros. rereleased the “Director’s Cut” into a few art house and revival theaters. However, despite the 1969 version receiving an R-rating, the MPAA demanded the picture be sacked with a new rating of NC-17, which prevented the studio from launching a wider distribution campaign. Regardless, in the years following its release, the Western declined in popularity, perhaps because of films like The Wild Bunch, whereby audiences began to recognize that the romanticism of the American West was an illusion and that, in fact, the era of Manifest Destiny was ridden with lawlessness, savagery, and genocide. Some might consider it progress that moviegoers no longer wanted to live in that illusion.

It’s difficult to imagine seeing an abridged version of The Wild Bunch and greeting it with anything but emotional distance, if not pure loathing. Only with Peckinpah’s flashbacks and backstories do we understand how worn down these characters are, and how they’re plagued, not unlike the alcoholic director himself, by their past misdeeds and inability to change. Pike has never changed, unlike Thornton, who has had no choice but to transform himself to survive—and that’s all it is, survival. There’s no life in Thornton left. He’s been broken in prison and under Harrigan’s employ; he carries on like a zombie, bereft of life with memories of his days alongside Pike running through his head. At the same time, Pike has begun to look at himself, his callousness and lifestyle. He knows his Bunch’s code is hypocrisy and is violated whenever it pleases him. “We’re not gonna get rid of anybody,” he barks in an early scene after the Starbuck ambush. “We’re gonna stick together, just like it used to be! When you side with a man, you stay with him. And if you can’t do that, you’re like some animal, you’re finished—we’re finished—all of us!” Throughout the film, Pike is haunted by his past, his failures, and his persistent inability to live up to his own code. He may preach about the importance of sticking together, but he leaves Bo Hopkins’ Crazy Lee in Starbuck to serve as a distraction for the others to get away; after the heist, he kills a member of the Bunch who would only slow the others down; in flashbacks, he scurries out the window and leaves a wounded Thornton to face the authorities—“How it used to be” indeed. Finally, there’s Angel, who’s handed over to General Mapache by Pike. This last betrayal weighs on Pike, until the final sequence when he fully—and finally—embraces his own code and enters the bloodbath in a grand act of attrition. Thornton cannot help but admire Pike and his ideal, even if he knows first-hand how often it has failed.

Under a fake mustache, the actor protested having to wear, Holden channels his director, capturing his authority and vulnerability. On the first day of shooting, Holden thought he was going to coast through the part until he saw how much Peckinpah was demanding from the supporting cast—the scrappy bounty hunters T.C. (L.Q. Jones) and Coffer (Strother Martin). Once Holden realized what Peckinpah would surely demand from his lead, he returned to his trailer to develop the character into a complex performance, one of the best in his career. Holden carries the weight of his years on his inward bent shoulders. “We gotta start thinking beyond our guns,” Pike warns the others. “Our days are closing fast.” There’s a scene after the Starbuck ambush where Pike, having been shot in the leg, falls off his horse. He tries to maintain his dignity and mount his steed, but the stirrup breaks and he falls. The Gorch brothers laugh as Pike pulls himself up. Wounded, he gets back on his horse and rides over a dune. Peckinpah keeps the camera on Pike’s back, the silhouette outlining this sad, defeated man. Before long, everyone on set, save for Peckinpah himself, realized that Holden was playing Peckinpah. The director’s children later remarked that Holden’s performance was so close to their father it gave them chills.

Under a fake mustache, the actor protested having to wear, Holden channels his director, capturing his authority and vulnerability. On the first day of shooting, Holden thought he was going to coast through the part until he saw how much Peckinpah was demanding from the supporting cast—the scrappy bounty hunters T.C. (L.Q. Jones) and Coffer (Strother Martin). Once Holden realized what Peckinpah would surely demand from his lead, he returned to his trailer to develop the character into a complex performance, one of the best in his career. Holden carries the weight of his years on his inward bent shoulders. “We gotta start thinking beyond our guns,” Pike warns the others. “Our days are closing fast.” There’s a scene after the Starbuck ambush where Pike, having been shot in the leg, falls off his horse. He tries to maintain his dignity and mount his steed, but the stirrup breaks and he falls. The Gorch brothers laugh as Pike pulls himself up. Wounded, he gets back on his horse and rides over a dune. Peckinpah keeps the camera on Pike’s back, the silhouette outlining this sad, defeated man. Before long, everyone on set, save for Peckinpah himself, realized that Holden was playing Peckinpah. The director’s children later remarked that Holden’s performance was so close to their father it gave them chills.

The Wild Bunch is seasoned with acting that looks and feels not like performances by great actors, but an ensemble of full embodiments. Ryan has a charmed mystery about him, his Thornton both amused and defeated by the hand fate has dealt him. During his pursuit he admires Pike and the Bunch, knowing that his present company has none of the honor or integrity maintained—or at least sought after—by Pike’s gang. After the final bloodbath, Thornton joins Sykes, the only remaining member of the Bunch, and they ride off together. Borgnine had been an affable supporting player for years, capable of creating both despicable villains in From Here to Eternity (1953) and Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) or the lovable sort he plays in Jubal (1956). Peckinpah originally resisted casting him because of association with the popular comedy McHale’s Navy, but Borgnine’s Dutch has personality and loyalty that comes out whenever the others challenge Pike’s authority. In the final bloodbath, once Pike goes down the last sounds we hear are Dutch’s desperate, saddened cries so filled with loss. “Pike! PIKE!” over and over. O’Brien, though frail and sickly offscreen, plays Sykes like a classical, yet hardened old timer. When he lashes out at the Bunch for asking which ‘They’ set them up, at first he’s comical: “Oh my, what a bunch! Big tough ones, huh? Here you are with a handful of holes, a thumb up your ass, and a big grin to pass the time of day with.” But then he sours. “They? Who the hell is ‘they?’” he says with a look and sound of absolute disgust, his teeth worn down to nubs, his beard browned from smoke and drink. Equally complex are Jones and Martin, both so overloaded with pathological whimsy that their comic crudeness is almost joyful in its despicableness. Peckinpah allowed the two actors to improvise many of their lines, and the result feels like two rambunctious brothers or a married pair of wily old cannibals.

More than the violence, The Wild Bunch is affecting for the absolute spiritual bankruptcy that prevails throughout the picture. Through flashbacks and Holden’s pensive expressions, Peckinpah intimates that Pike has nothing to show for his years. Pike’s proverbial “last job” in Starbuck backfired and, concerned about Thornton’s posse, he tells Dutch they should back off somewhere. “Back off to what?” Dutch asks. “Have you got anything lined up?” Pike knows he has led an almost pointless, fruitless existence, his seemingly honor-bound ways convoluted and betrayed on a whim. He, at last, realizes this to its full scope when, after taking shelter in Mapache’s stronghold to hide from Thornton, he visits a young Agua Verde whore—the kind of place Peckinpah had visited plenty of times in his frequent trips to Mexico. As he dresses afterward, he looks around the room and notices her baby tucked into the corner. Disgusted with himself and everything around him, he resolves to finally make his code stand for something and lead his Bunch to their deaths in honor of Angel. “I want to be able to make Westerns like Kurosawa makes Westerns,” Peckinpah once said, perhaps realizing how Kurosawa at once embraced Japan’s traditionalism and history while he exposed its hypocrisies. The ending of The Wild Bunch is not unlike the honorable decision of the few warriors from Seven Samurai (1954) to defend a small village of farmers from a huge gang of raiding bandits in what could only be a suicide mission.

More than the violence, The Wild Bunch is affecting for the absolute spiritual bankruptcy that prevails throughout the picture. Through flashbacks and Holden’s pensive expressions, Peckinpah intimates that Pike has nothing to show for his years. Pike’s proverbial “last job” in Starbuck backfired and, concerned about Thornton’s posse, he tells Dutch they should back off somewhere. “Back off to what?” Dutch asks. “Have you got anything lined up?” Pike knows he has led an almost pointless, fruitless existence, his seemingly honor-bound ways convoluted and betrayed on a whim. He, at last, realizes this to its full scope when, after taking shelter in Mapache’s stronghold to hide from Thornton, he visits a young Agua Verde whore—the kind of place Peckinpah had visited plenty of times in his frequent trips to Mexico. As he dresses afterward, he looks around the room and notices her baby tucked into the corner. Disgusted with himself and everything around him, he resolves to finally make his code stand for something and lead his Bunch to their deaths in honor of Angel. “I want to be able to make Westerns like Kurosawa makes Westerns,” Peckinpah once said, perhaps realizing how Kurosawa at once embraced Japan’s traditionalism and history while he exposed its hypocrisies. The ending of The Wild Bunch is not unlike the honorable decision of the few warriors from Seven Samurai (1954) to defend a small village of farmers from a huge gang of raiding bandits in what could only be a suicide mission.

To see beyond the tremendous exhibition of violence in the picture and recognize the profound degree of human introspection is the central challenge of The Wild Bunch. Pike’s self-reflection serves as a reminder to the audience to consider the history of the American West with a more critical view than blind romanticism. The film encapsulates Peckinpah’s own arguments on humanity—that we’re all just a bunch of savage animals, nevertheless capable of what might be characteristically described as “humanity”. The shorter versions of the film abridged in 1969 completely miss this point by removing the human touches—the motivations discovered in backstories—in favor of pure cinematic escapism and violent thrills. No film that considers such self-reflective characters or situations could be a pure celebration of violence, as The Wild Bunch’s harshest critics maintained, whereas detractors from Peckinpah’s original cut who condemn its violence have ignored not only the truth in the director’s message but the viciousness of the human race. Peckinpah’s metaphor for and representation of humanity is an extension of his more specific commentary on what might be our most human point in history: the American West, where all of our idealistic notions about freedom and discovery are transformed into something wild and unabashedly violent. Such is the allure of the Wild West and The Wild Bunch, a complex of romanticism stained in blood.

Bibliography:

Kael, Pauline. “The Wild Man.” The New Yorker . 8 Nov. 1999: 98-100. Print.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Weddle, David. “If they move… Kill ‘Em!”: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah. New York: Grove Press, 1994.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review